Well, this might have worked in rural Queensland, but the good citizens of Newcastle did not feel the need to make “Dr. Sir George Russell” part of their medical fraternity.

The bright lights of Sydney

A few months later, Professor Russell fetched up in Sydney, opened premises at 146 William Street, and began to advertise in the Sydney Morning Herald almost constantly. One would think, looking at the advertisements, that this gentleman had a very large portfolio of property to rent out:

- A furnished house to let, 3 rooms and kitchen. Professor Russell, 146 William Street.

- FURNISHED HOUSE, 5 rooms, to let. Every convenience. Ten minutes from Post-office.

- At Professor Russell’s, 146 William Street, To LET, furnished front ROOM, gas and bath.

- A HOUSE to LET, comfortably furnished; piano, bath, hall; Professor Russell, 146 William Street.

- A COTTAGE to LET, comfortably furnished, 4 rooms. Professor Russell, 146 William Street.

- A COMFORTABLY furnished HOUSE to let in Woolloomooloo. Professor Russell, 146, William-St

This Professor Russell was also a dentist, apparently:

- WANTED, visitors to Sydney to get their TEETH CLEANED without pain, inconvenience, or injury to the enamel; ten minutes, and no acids are used; charge 2s 6d. Professor Russell, 146 William Street.

(Mrs Professor Russell from Queensland was nowhere in sight at this stage.)

1878 saw Professor Russell engaged in his usual activities – cutting hair and advertising properties to let. Things became a little unusual when Inspector Doyle from the Australian Gaslight Company, acting on information received, turned up to have a look at the meter in his shop. Doyle was accompanied on this raid by five of his finest gas investigating men.

A young woman at the counter set off an alarm, which summoned forth the Professor himself, who immediately ducked under the window and turned off the gaslights. Nothing suspicious about that…

It transpired that there was a secret gas connection in the basement of Professor Russell’s premises, and through this, gas was being redirected from a neighbouring building.

Doyle delivered a line that should be immortal in the annals of criminal investigation: “As inspector of the Gas Company, I accuse you of stealing their gas,” to which the Professor made no reply. Probably because it all sounded rather surreal.

The Professor called upon the Australian Gaslight Company repeatedly, hoping to see a Mr Mansfield, with whom he could discuss settling up and avoiding any tiresome charges. Mr Mansfield chose to be unavailable on every occasion.

A charge of stealing was laid by the actual police, who testified at the Professor’s committal hearing that they had been watching the address, and noticing how many lights were burning late into the evenings, and how many cabs going there. Funny that they should be watching a man’s lights and visitors.

PUBLIC NOTICE. – The person that styles himself Professor Russell, hairdresser, whose name appeared in the public press recently, is in no way connected with Mr. Phill. Russell, Pianist, of Liverpool- Street.

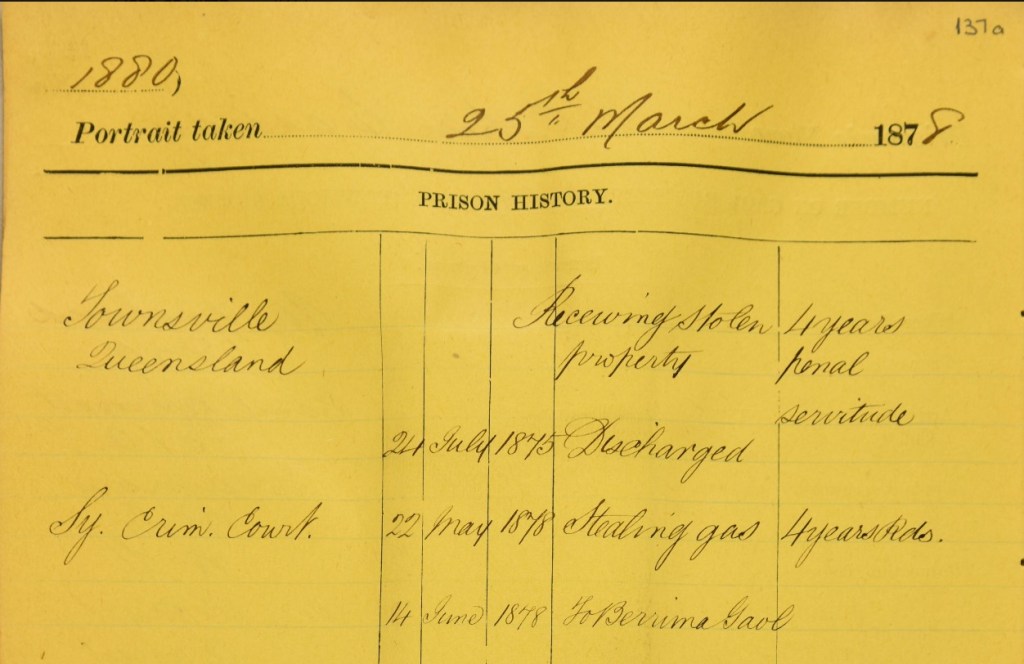

In June 1878, George Russell was found guilty of “stealing 50,000 cubic feet of carbureted hydrogen gas, valued at £17 10s., and the property of the Australian Gaslight Company.” The judge gave him four years’ hard labour in gaol.

Why the severe sentence for nicking next door’s gas? The Brisbane Courier was happy to oblige with an explanation:

CONCERNING the sentence just passed on Russell, the Professor Russell of Queensland celebrity, the Sydney Echo says:-“There are few more painful sights to behold than one of assured crime on the part of an educated and intelligent man.

Such was the case this morning, when the now notorious George Russell, who adopted the title of Sir George Russell, was sentenced to four years’ imprisonment, with hard labour. The son of a respectable tradesman, whose name he has happily dropped, he was well brought up, but very early acquired vicious habits; and so he went on until, commencing with a four years’ sentence in Queensland, he proceeded from bad to worse, and is now undergoing a similar sentence here. The prisoner, as Sr William Manning pointed out, was evidently possessed of both intelligence and education, and these circumstances rather increased than otherwise the severity of the sentence. Though nominally for gas-stealing, the fact that the prisoner had leased no less than seven houses for immoral purposes, perhaps weighed with his Honour in giving Russell the sentence he did.”

The Protestant Leader explained further:

“His trade was this — When he saw a vacant house, in a suitable place for his purpose, he offered to lease it for one or more years. He did not stickle about the rent. He even offered more than others would do. In one case known to us he offered double the usual rent. If a covetous landlord was caught by this offered money and leased the premises, this professor somehow got furniture placed in them and let them, furnished, generally to those who can pay well — to prostitute women and their friends. If the police were put on his houses as brothels, the women were removed in a day to another of his places, and a fresh lot installed in their rooms. Like a good general, and knowing that his tenants were peculiar, several times a week would he take a turn round them; and, on the Monday morning he was always early, knocking up his night-tired debtors, that his money might be secure.”

A defamation case brought by Bernard Bogan, one of the owners of the properties Russell had sub-let, was brought against the Protestant Leader in 1879, and the evidence explained Russell’s activities in detail. Mr Bogan lost. Russell was in gaol until early 1882.

Sweet home Goulburn

On his release from prison, Professor Russell needed a place to set up business. Sydney was out of the question, given his well-publicised adventures in sub-letting. Queensland was too lightly populated and provincial to have forgotten his earlier disgrace. Victoria, well, he had left there in a hurry to avoid creditors.

Hoping that the good people of Goulburn had little interest in metropolitan affairs, Professor Russell came to town in 1882, and set up shop there, offering hairdressing, of course, together with painless dentistry. A very brief mention appeared in the papers of the happy news that Margaret Bullock had married George Russell in Sydney on 2 August 1882. Both of Goulburn.

It was a new start, it seemed. Professor Russell was busily taking other people to court -for assault, or for nicking things. Rather harshly, he charged a four-year-old child with stealing and lost a subsequent civil suit to the boy’s indignant mother. He did face a couple of minor municipal charges (putting an advert where he shouldn’t have etc), but on the whole, life was good.

He was even praised for his good taste:

AS an example of high-class decoration in Goulburn the verandah of Professor Russell stands, perhaps, unrivalled. The job was executed by Mr. Quartly and his workman, and apart from the excellent manner in which the purely manual part of the work has been performed, the taste displayed in the selection of colours is very rarely met with in house-decoration.

The greater part of the front has been painted in white and gold, but anything like a dead monotony has been avoided by the variety of colours introduced. Three sorts of marble are shown, the fasure board being Italian, the base Broccadella, and the panels let in at the sides of the window Irish green. The window itself, which is of British plate, is frosted with crimson lake, rimmed with purple; whilst the body of the lettering on it is of gold. The painting of verandah-the supporting columns of which are grained in Irish green marble and have tops of grey and gold-corresponds with that of the window.

That’s quite a verandah.

A Birth and a Death

A son was born in January 1884, and announced thus:

Under Dr. McKillop’s care at 7 o’clock on Monday Evening, 14th January1884, Mrs Professor Russell of a Big Son, exactly like—any other baby.

And then, on April 11, 1884, Professor Russell died suddenly. He had been anxious about a summons case due to be heard the following day and took some pills to send him off to sleep.

The pills, prescribed by his doctor, contained morphia, and he had been advised not to take any other medicines with them. He had gone to sleep with the baby on his arm as usual, and then his wife noticed his breathing had become heavy, and he couldn’t be roused. The inquest verdict was as follows:

“That deceased came by his death from an overdose of morphia administered by his own hand, but that there was no evidence to show that he had taken it with the intention of causing death,” and they added the following rider: “We hope the unfortunate incident will act as a caution to others against using narcotics.”

Who was Professor Russell?

According to his New South Wales Gaol admission notes, he was George Russell, born in London in 1841. He had emigrated to Australia in 1846.

In Queensland, however, Professor Russell had been calling himself George Albert Norton Russell, and there is a record of a person of this name.

The real George Albert Norton Russell was born in Sydney on 23 August 1842. His father was George Norton Russell, and his mother was Eliza Hart. George Albert Norton Russell was married in Sydney on 7 September 1870 to Elizabeth Wilkie.

At the time of the wedding in Sydney, Professor Russell was in Brisbane, trying to obtain a hotel licence, and placing advertisements in the Courier, advising that he would accept copper tokens for his services, and that he would not be responsible for any debts contracted in his name without his personal authority.

George Albert Norton Russell (the real one) was widowed in 1875 and remarried that year to Henrietta Duncliff. He fathered five children and died after a long, full life in May 1912.

George (Professor) Russell must have been aware of his more illustrious near-namesake when living in Sydney and appropriated the handle for his own use in Queensland.

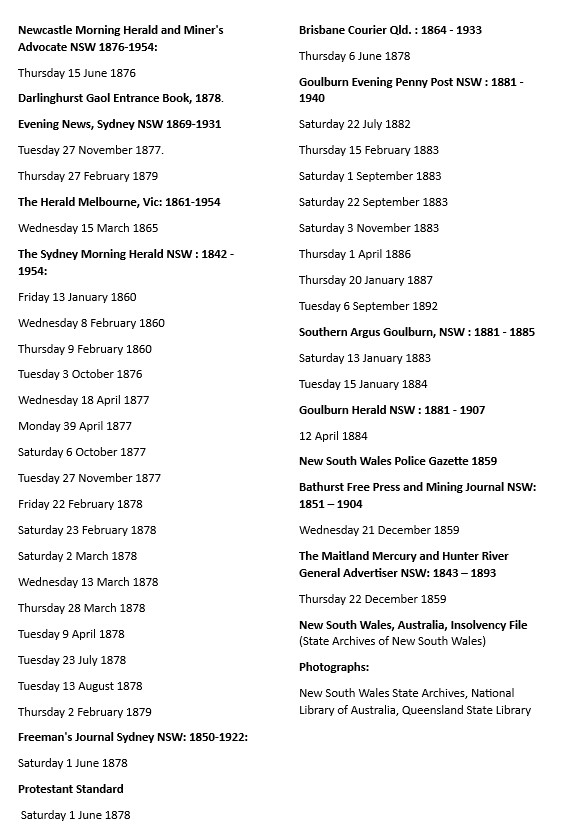

1859 – A Charge of Stealing and an Audacious Escape

So, who was he? The earliest solid clue appears in the New South Wales Police Gazette in 1859:

A warrant has been issued for the apprehension of George Russell alias Brown, charged with embezzling the sum of £100 the property of his master Henry Chatto. Description – he is about 18 or 19 years of age, about 5 feet 5 inches high, medium build, walks upright and quick, light hair, round effeminate features, ruddy complexion, no whiskers, nose inclined to Roman rather sharp, prominent grey eyes, retreating mouth and chin; had on when last seen a black sac coat, black trousers and cap.

For nearly two months, George Russell was sought throughout New South Wales, with Henry Chatto offering a reward of £10 to anyone who could bring Russell into custody.

In December, young Russell was in custody in Wellington. For a little while. Somehow, he had access to a small saw and cut through the slab walls of his cell to freedom. He didn’t spend too long on the run, managing to walk for seven hours, and crossing the Macquarie River twice, only to turn up in a hut that was frequented by the brother of the lockup keeper. He was recaptured and put in chains for his journey to Sydney. The Wellington escape plan would be repeated, rather less successfully, in Townsville twelve years later.

On February 8, 1860, Russell entered a plea of guilty to stealing. He made a statement that he had inadvertently lost £25 belonging to Mr Chatto, panicked, and committed the larger theft to cover it. Mr Chatto was unimpressed by his excuse, and the Bench gave him one year with hard labour in Parramatta Gaol.

These details of Professor Russell’s early life are repeated in a series of articles about “the convict, Russell or Brown” that were written after his 1878 conviction for stealing gas. These articles also mentioned his hairdressing past, and his brief use of the title “Sir George Russell.”

1865 – Hairdressing in Victoria

In 1865, we find Professor Russell in Victoria, advertising “FOR SALE for the value of fittings, etc, the best HAIRDRESSER’S in Sandridge, doing £4 per week; ‘Herald’ agency connected, bringing in upwards of 30s. weekly.” Later articles would suggest that he had learned to cut hair in Parramatta Gaol, and in between criminal enterprises, hairdressing was how he made his living.

Having left the colony of Victoria, and possibly quite a few creditors, behind, he headed for Sydney to make a living as Professor Russell the hairdresser.

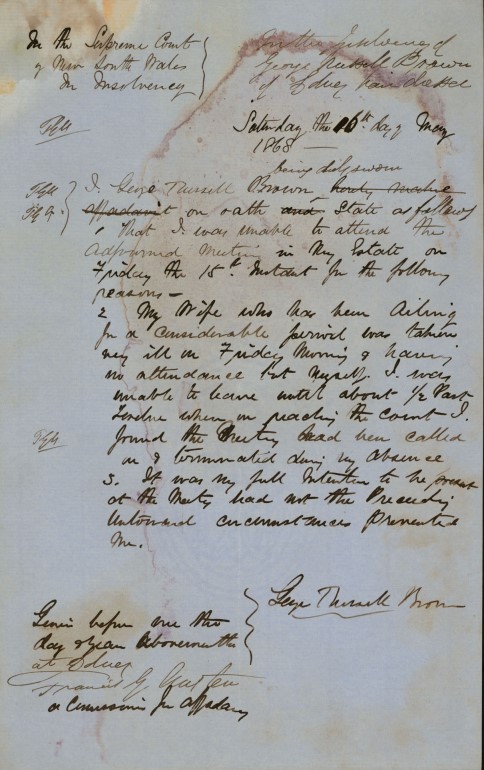

1868 – Insolvency in Sydney

The Pitt Street hairdressing business was not successful, as the Insolvency File of May 1868 attests. In the file, he is listed as George Russell Brown, hairdresser, of Pitt Street, Sydney, who still owed £17 after everything he owned had been sold up.

In the file is a letter from George Russell Brown explaining his failure to attend the court’s insolvency meeting on Friday 15 May 1868. The affidavit appears to have been written in haste but despite the crossings-out and flustered penmanship, is legible. Russell explains that his wife had been ailing for some time and had taken a bad turn that morning, and he was obliged to remain at home that morning. The wife is presumably the Mrs Russell he brought to Brisbane several months later to tend to the hair of the ladies of Brisbane. She worked with him there for three years and must have made a remarkable recovery to do so.

The Mrs Russells

The first Mrs Russell is a shadowy figure. She was named as Emma Russell in newspaper reports of her husband’s conviction in 1872, but there are no records of who she was or where she went after the scandal.

There were two children born to a George Russell and his wife Mary in Queensland between 1868 and 1871, but those were country births, and probably not the progeny of the Professor, who resided in Brisbane.

There are no marriage or divorce records for a George and Emma Russell in Queensland, Victoria or New South Wales for the period 1860 – 1882. Emma might have been the name Mrs Russell chose to use, rather than her actual given name. Presumably, after the scandal, the first Mrs Professor Russell quietly found another name to use and place to reside.

The second Mrs Russell is easier to locate. Her name was Margaret Beattie Bullock, and she had married to one James Bullock in 1858 at Goulburn. James Bullock was charged with beating her on two occasions in the 1860s, and they appeared to have parted ways in the early 1880s.

Margaret Bullock bore James twelve children during their time together, most of whom survived into adulthood. Mr and Mrs Bullock never divorced, and James Bullock left Goulburn. James went missing in Jindabyne in 1885, the evidence pointing to a drunken fall into the river (his hat and other belongings were found in the water, and prior to his disappearance, he’d been staggering about with a bottle of liquor in his hand).

Because they didn’t divorce, James’ estate went to “Margaret Beattie Bullock, commonly called Russell, of Goulburn, in the said colony, the widow of the said deceased. Dated this 20th day of January A.D. 1886.” (New South Wales Government Gazette.)

Margaret’s marriage to George Russell in 1882 appears not to have taken place and was merely advertised in a Sydney newspaper for propriety’s sake. When their son George was born in January 1884, the entry on the birth certificate became the subject of the summons to Court that Professor Russell had been anxious about on the night he died.

Margaret Russell was less uncomfortable with the idea of the case – most of Goulburn must have known that her remarriage was a polite fiction – and gave evidence about it at the inquest, quite frankly mentioning her “alleged marriage.” But for Russell, this charge could have exposed just about everything he had been keeping quiet about. His identity, the non-marriage, the possibility of bigamy charges, the illegitimacy of his child, and his criminal history.

Widowed, Margaret carried on as Margaret Russell, or Mrs Professor Russell as she like to be called, dealing with irate neighbours, being charged with swearing (hotly denied), dealing with a large family, and (hotly denied) allegations that her nice hairdressing establishment was a place of resort for prostitutes. She died in 1892. The son of her relationship with Professor Russell, also George, lived on until 1941. He was three months old when his father passed away.