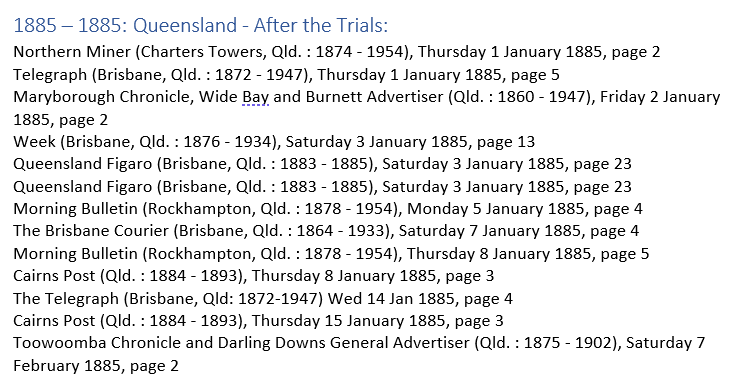

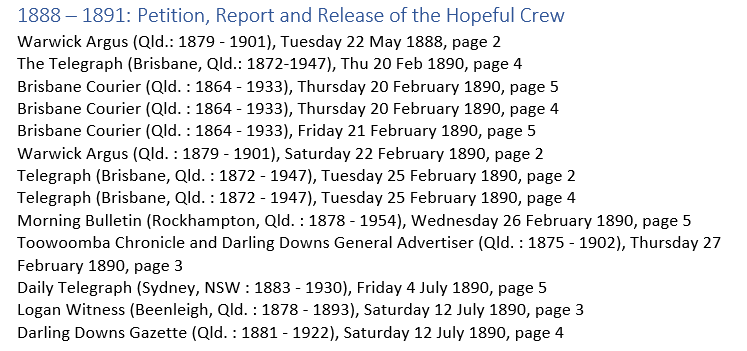

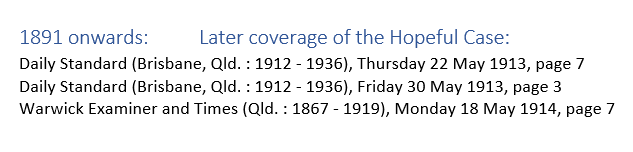

At the commencement the feeling against the accused was very, strong, but as the story unfolded itself, and the crown witnesses were found, with one exception, to be coloured people-the solitary exception being a disgruntled ship’s carpenter belonging to the Hopeful-some of whose evidence was strongly suspected of being tainted, a complete revulsion of feeling took place, and instead of the prisoners being greeted with howls of execration, open sympathy was shown them…

Warwick Examiner and Times, Monday 18 May 1914

This quote sums up a good deal of the coverage of the murder and kidnapping trials that took place after the voyage of the schooner Hopeful.

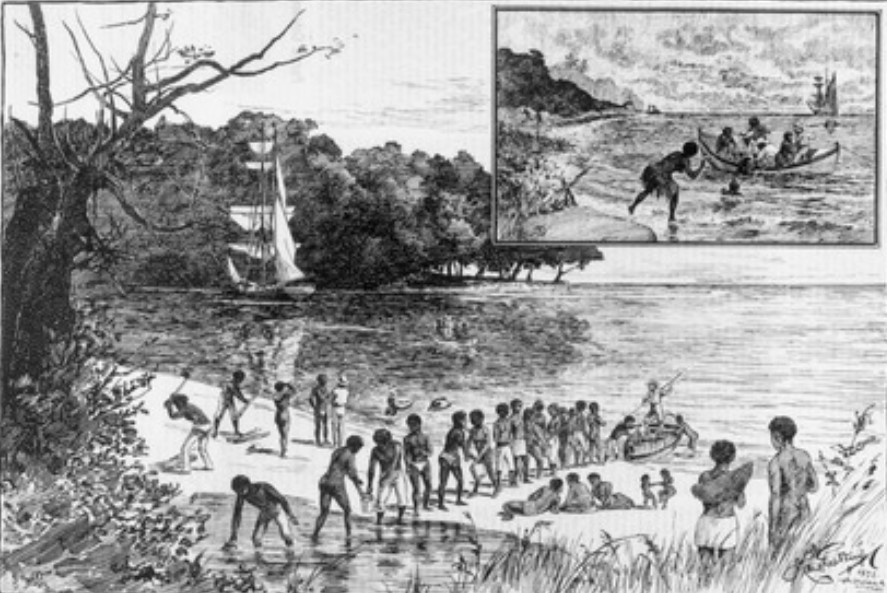

South Sea Islander labourers at Hambledon Plantation, Cairns,1890s (SLQ)

In 1884, a man named Albert Messiah was hired on to the “labour recruitment” schooner Hopeful, as a cook and able-bodied seaman. During that voyage, he witnessed violent criminal activity on the part of certain crew members, amounting to the kidnapping and murder of New Guinea islanders.

When the schooner returned to Townsville with its cargo of labourers from the islands, Albert Messiah travelled to Brisbane and laid a criminal complaint. Messiah became the chief, but by no means the only, witness for the prosecution of several crew members of the Hopeful.

The Hopeful’s second officer and recruiting agent Neil McNeil and boatswain and mate Bernard Williams were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death (both sentences were quickly commuted). James Preston, Edward Rogers, Lewis Shaw (Captain), Thomas Freeman and Harry Schofield were convicted of kidnapping, and were sentenced to long terms of imprisonment. Harry Schofield died in custody in 1886. The surviving prisoners were released in early 1890 after years of public campaigning for clemency.

Albert Messiah was a complicated figure as a witness for the Crown. He had a conviction for dishonesty in Tasmania several years prior and had contacted one of the accused crewmen to ask for money before laying the complaint. He admitted to these character drawbacks but did not back down from his evidence about the Hopeful.

After the Hopeful trial, he went to live in Sydney, married, became a father, and lived a law-abiding life. His family adored him. He was well-known and liked in Sydney as the “corn doctor,” who treated the corns and bunions of thousands in the metropolis for a small fee. He joked that unlike other doctors, he had never had a patient die under his care.

Albert Messiah was a Black man – born in Antigua around 1853. This fact, more than anything else, seems to have informed public discussion about the trial and convictions in the Hopeful case.

Labour “Recruiting” in Queensland

Queensland is a very good place to grow sugar cane. The climate is tropical in the North and sub-tropical in the South. The sugar plantations that were set up from the 1860s onwards required a lot of manual labour, preferably cheap manual labour, to be profitable.

One Robert Towns set up cotton and cane farming on the Logan River and imported labourers from New Caledonia and Vanuatu by the hundreds. His success led to him establishing plantations in North Queensland and staffing them with workers from the South Sea Islands. These workers were often induced by trickery, or frankly kidnapped, kept at work for three years for a pittance, and then, if they were lucky, returned to their (correct) homelands. Indentured labour was so vital to the sugar industry that the city of Townsville was named after Robert Towns.

By the 1880s, the labour recruitment industry was meeting armed resistance from inhabitants of its usual hunting grounds. New Guinea was seen as a convenient alternative, and that is where the Hopeful headed in 1884.

The Shooting at Sanaroa

Messiah gave evidence that on 13 June 1884, the Hopeful was off Sanaroa. Some islanders in canoes made for the ship to make some trades. In one canoe, a man had a sucking pig ready to offer up.

Two of the Hopeful’s boats were lowered, and the islanders, noticing the presence of white men with guns, turned to row back to shore. Messiah was watching from one of the boats, as was another Crown witness. The closest canoeist dropped the sucking pig and took up his paddle to fend off the Hopeful’s men. After a short struggle, Neil McNeil shouted, “Drop the ________,” and one of the Hopeful crew members fired at the canoe but didn’t hit anyone. McNeil, who had been speared some weeks earlier, then shouldered his rife and fired directly at the man in the canoe, about five yards away. The man fell and he did not get up. The other islanders in the canoe jumped into the water, leaving behind the man who had been shot and a small boy, who was crying.

Bernard Williams, an American working as boatswain, fired on an islander who was in the water. The man who was shot did not resurface.

The Hopeful’s boats picked up six of the islanders from the water and took them on board as labour recruits. As they passed by the canoe, the man lying there had not moved, and appeared to be dead. At the time, Messiah said, the captain (Lewis Shaw) of the schooner was on the aft poop, and the Government Agent (Harry Schofield) was drunk below deck.

Edward Dingwall, a carpenter on board the Hopeful, gave evidence that broadly corroborated that of Messiah. He didn’t recall the exact date but was able to describe the shooting incidents and the behaviour of the Hopeful crew. Dingwall was a white man, who, like Messiah, harboured no affection for the recruiters. He had been in trouble for failing to pay his wife maintenance prior to boarding the schooner, a fact seized upon by the defence.

Then a group of New Guinea and South Sea Islander men gave evidence for the prosecution. They were able to give vivid evidence as to the shootings and corroborated the evidence of Messiah and Dingwall. These men were all referred to as ‘boys.’ They were: Jack (who was a native of Miva and spoke English well), Charlie (from Santo), Harry (from Aboa), Cargo (an interpreter, from Burra Burra), and Dianamo from Sanaroa (who relied heavily on interpreters).

In the cases of these men, an allegation was raised by the defence that they had been in contact with, and probably coached by, Albert Messiah. The contention that these men were unable to give evidence of their own experiences was directly tied to their race. A further objection was raised to their evidence being accepted when they swore no Christian oath.

Not a Perfect Witness

The Supreme Court, Brisbane, (SLQ)

Albert Messiah’s life history in his own words. Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Friday 5 December 1884, page 5.

Under cross-examination, Albert Messiah admitted that he had not spoken to anyone about the events on board the Hopeful during the time the vessel was in Dungeness, when the boat was boarded by various officials, nor during the ten days he was at Townsville. His life, he said, would have been in danger if he had raised the issue in Far North Queensland, which relied so heavily on the sugar and recruitment industries.

He admitted to sending a telegram to Henry Schofield, asking him to pay £20, or he would have him arrested. After receiving a reply from Schofield, Messiah went to Captain Marks in Brisbane, and made a formal complaint. He had also, he said, made a statement to Mr Philp of Burns, Philp and Co (who owned the Hopeful) about the events of the voyage, but the statement had been burned after he gave it.

Messiah admitted that he had sold scrip for a worthless tin mine in Tasmania, but claimed to have done so without knowledge that the mine was not productive. This had resulted in his prosecution and imprisonment. He said that he was made a scapegoat for the mine’s failure.

In the course of his evidence at the separate trials for murder and kidnapping, Albert Messiah was asked whether he had framed Neil McNeil because he had “a down on him,” and would see him hanged. He denied this. He was asked about whether he had been intimate with female labour recruits. He denied this also.

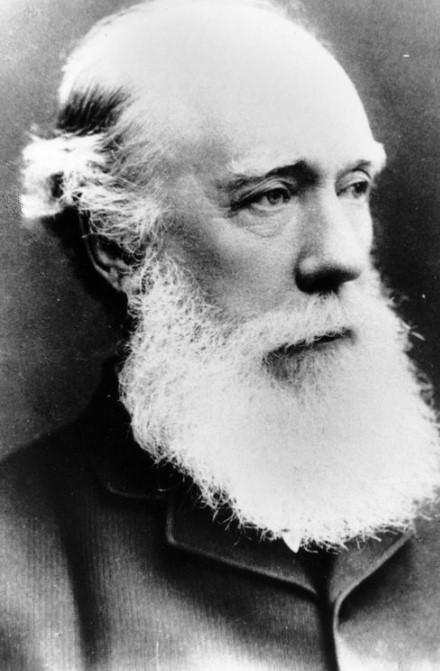

Sir Charles Lilley Sums Up

On neither side did the witnesses stand perfectly clear, and what was said on the one side might be said with an equal degree of truth on the other side, and if they waited until they got witnesses perfectly clear of blemish, they would very seldom get justice administered.

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Friday 28 November 1884, page 5.

Sir Charles Lilley, Chief Justice, 1879 (SLQ)

Sir Charles Lilley gave painstaking instructions to the jury in the Hopeful trials. He summed up the evidence for both sides, reminding the jury that they may choose to believe the evidence of one witness over another, or to disbelieve all the witnesses if they chose. There was no such thing as a perfect witness. In both murder trials (McNeil and Williams) and in the kidnapping trial, the juries found the Hopeful crew members guilty.

The Backlash

The backlash against Albert Messiah personally began almost immediately. He was decidedly unwelcome in Brisbane, having been, in the eyes of the newspaper-reading public, the coloured man who sent two white men to the gallows. The remission of the capital sentences to long terms in custody did little to calm the mob. Messiah moved to New South Wales, married, and began another life. He did not, as scurrilous newspaper reports in Queensland suggested, become a Justice of the Peace in North Queensland, nor was he ever sworn in to lead the Native Police, as a reward from the Government.

It was stated on Christmas night on very good authority that the hero of the Hopeful trials, Mr Messiah, who has been residing somewhere in Charlotte street, was serenaded that evening by a large number of waits. The chorus was a very powerful one as far as voices went, but there was something sublime in the vigorous and unanimous manner the stones and brickbats were disposed of. Probably the house is now the best ventilated in Brisbane, as it is stated that not a pane of glass two inches square was left after the ceremony.

The Week (Brisbane, Qld.: 1876 – 1934), Saturday 3 January 1885, page 13.

The Petition for the Hopeful Prisoners and Sir Charles Lilley’s Response – 1888-1889

So much horror was expressed about the fact that the Hopeful’s crew were sitting in prison, to the petitioners’ minds, solely on the word of Albert Messiah, that a series of petitions were sought for their release in 1888. In these documents, the petitioners based their claims on several grounds: –

- The untrustworthy character of Albert Messiah (who was at the time in Sydney, blamelessly tending to the aching feet of commuters at Central Station);

- The then Government desired to end the labour recruitment trade by making an example of the Hopeful crew, while others had done exactly the same thing and not been punished;

- The possibility that the Sanaroa men who had been shot had not in fact died; and

- The decision to hold the trial in Brisbane, leading to a belief that exculpatory evidence had not been presented as a result.

Sir Charles Lilley was called upon to address the issues raised and did not hold back.

“Can there be any doubt that the cruise of the Hopeful was bloody and lawless and that the murders and kidnapping of the 13th June were not connected with its whole course?”

Sir Charles Lilley

Lilley defended the conduct of the trial and opined that no further relief should be given to the prisoners, beyond their reprieve from the gallows.

“It is said that three of the witnesses whose statements were in the hands of the Crown Law officers should have been called by them. Their statements … (contain) nothing material that could in any way affect the verdicts.” It was a matter for the prosecution to decide which witnesses to call. The option of calling these witnesses had remained open to the defence, and their input had not been sought.

As to the possibility that the canoeist and another man (shot by Williams while swimming) survived:

“Now the Jurors had all these men (crew) before them, and they believed that the shots were fatal. If men are fired at point blank at a short distance and hit with a rifle ball, and the one lies in his blood seemingly dead for half an hour, and the other a swimmer at a distance from land throws up his hand and sinks and is not seen to rise again, it cannot be said that the Juries were unreasonable in inferring that both had died. The evidence of the Doctor must be taken with the circumstances deposed to by the other witnesses in coming to the conclusion as to whether the men were shot dead.”

As to the idea that the men were convicted solely on the evidence of a person of colour who had a criminal record, he reminded them of the other evidence:

“As to Messiah’s character, the men who engage in kidnapping are not usually accompanied by scrupulous persons, and if we rejected the evidence of such persons altogether the kidnappers would find a security by employing persons of the worst possible character.”

“‘Without his evidence there could have been no conviction,’ this is a grave error. The case for conviction did not rest solely on Messiah’s testimony.“

And the petition? It was misguided, said Sir Charles:

“These allegations show the way in which humane men have faltered with their consciences in seeking excuses for these inhuman outrages on black humanity.”

A marginal note on the report, made by one of the recipients, did not like Sir Charles’ tone in that final statement – “A great blot in this report. In effect charges the petitions with criminal sympathy with alleged outrages,” it sniffed.

Sir Charles was not preaching to the converted, and the remaining Hopeful prisoners were released in early 1890. They gave interviews to the papers and described their lowest point in prison as the occasion when the kidnapped islanders had been taken to the gaol to view their former captors, now in chains. The crew members all blamed Albert Messiah for their misfortunes.

There was a triumphant reception planned in Brisbane by supporters of the Hopeful’s crew, but it was quietly abandoned when cooler heads suggested that the men had been convicted of crimes in the labour trade, and that a party in their honour might be a bit too much.

In the end, the labour recruiting industry could not defend itself against claims of kidnapping and treatment that amounted to slavery, and the practice was stopped in the early 20th century. The Government, faced with the presence of rather a lot of coloured people, did what it thought was the best thing in the circumstances and deported as many of them as possible. After searching their baggage.

Albert Messiah in the Media

[Warning: the language used in these quotations is racist. But people actually said these things in the public press at the time, and that language was something Albert Messiah and other men of colour had to deal with. I have used the quotes with some misgivings, and in some cases, have censored one particular word with asterisks.]

Throughout his life, every report about Albert Messiah made mention of his colour. In Tasmania, he was portrayed as uppity, a black man who “paraded around,” and had the temerity to dress neatly and greet people whilst doing so. In Queensland, he was called “an arch scoundrel.”

1882 – Tasmania

A BLACK STORY. A coloured man named Albert A. Messiah, who may have been observed parading the street of the city for same time past, with an air of great importance, and who represented himself as the possessor of land at the West Coast, has come signally to grief, and is at present sojourning in the city lock-up.

The Mercury (Hobart) 28 January 1882

MR. ALBERT AUGUSTUS MESSIAH. A coloured gentleman rejoicing in the above combination of names, has been sporting about the city for the last month. Messiah dresses neatly, and gives a graceful salute to those he knows, or fancies he knows, and seldom loses an opportunity of entering into a conversation, when he holds forth, after the manner of Sir Oracle on the prospects of the West Coast.

Launceston Examiner (Tasmania) 31 January 1882

A SABLE SCRIP SELLER, rejoicing in the patronymic of Albert Augustus Messiah, hailing from the West Coast, has got into trouble in Hobart, through selling scrip in the Scottish Chief mine, the existence of which the purchasers strongly doubt. After selling, Mr. Messiah enjoyed himself, then joined Burton’s Circus Company, but being tired of waiting, he subsequently engaged as cook on board the ship Wagoola, which was on the point of departure for London. However, before the coloured speculator could get away, his victims set the law in motion, and he was arrested. He was brought up at the Police Court and remanded.

Telegraph (Launceston) 1 February 1882

1884 – Brisbane

From what can be gathered it seems that the cook, an African negro, named Messiah, has been to Brisbane and laid the charge that, during the last trip of the Hopeful, on the 13th of June, while the vessel was off Rabi Island, McNeil fired at one of seven or eight boys, in a boat alongside, shooting him through the chest, death being instantaneous. The story is deemed to be false here. The accused will be brought before the Court tomorrow, and a remand for eight days will be asked for to await the arrival of a warrant and the cook, Messiah, from Townsville.

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser 6 September 1884

Would a white cook have been believed? Doubtful. It would have needed to be a white officer, possibly an unblemished minor member of the aristocracy, making the complaint for anyone to believe that atrocities were occurring in the labour trade.

From what can be ascertained it would seem that a negro lately employed on the Hopeful as cook went down to Brisbane and informed the authorities.

Capricornian (Rockhampton) 13 September 1884

1885 and beyond – Queensland

As for Armit, everyone who knows that veracious writer rejects his story as a wild romance. Had that round of bloodshed actually occurred, do you not think that blackguard Messiah would have belched it out, ay, and embellished it with a few n****r lies? Of course, he would. The circumstance that he never mentioned any one of Milman’s alleged outrages, is proof positive.

Queensland Figaro (Brisbane, Qld.: 1883 – 1885), Saturday 3 January 1885, page 23

I clip this from the Sydney Evening News, 5th May: -“James Crouch, alias Kelly, an old offender, and William Doyle were, at the Central Police Court today, committed for trial at the next Quarter Sessions for an alleged assault on a black named Albert Messiah.” This Messiah is the n****r on whose evidence the “Hopeless Hopefuls” were convicted and are now lying in prison. Messiah found Queensland too sultry after the trial, and Ah Sam’s Government sent him to Sydney. It’s not all over yet!

Queensland Figaro and Punch (Brisbane, Qld.: 1885 – 1889), Saturday 12 May 1888, page 6

Figaro didn’t seem to notice that Albert Messiah was a victim of crime on this occasion.

This was decidedly rough on the great majority of members of both Houses (many his strong supporters) besides other leading citizens who signed a petition for the release of Captain Shaw, the master of the Hopeful, and many thousands of electors, while abhorring the outrages, feel that much of the evidence – especially that of Albert Messiah, the negro cook, an arch-scoundrel – was of a very unsatisfactory character, and that the crew of the Hopeful had probably been led astray by what is at all times a highly exciting traffic.

Warwick Argus (Qld.: 1879 – 1901), Tuesday 22 May 1888, page 2.

Yes, don’t blame the white men – they got carried away with all the exciting shooting and so forth. Blame the black man who informed on them.

All the prisoners pleaded not guilty to the various charges, but the jury in every case held them as guilty on evidence given by the cook and steward of the vessel, Albert Messiah, a West Indian black; Edward Dingwall, the ship’s carpenter, and four kanakas, who were on the ship’s roll at the time of the voyage.

Warwick Argus 22 February 1890, page 2

The chief witness for the Crown was the cook on board the Hopeful, a coloured man named Albert Messiah, who, it was an open secret, bore no love to either the officers crew of the vessel… and it has been a perpetual wonder to me that he escaped the vengeance of those who had been connected with the Hopeful case, or in any way associated with the labour trade in the South Seas.

Warwick Examiner and Times 18 May 1914

That was probably why Albert Messiah left Queensland in early 1885. He had already been threatened verbally and had his house attacked by a mob.

But in New South Wales, where Messiah lived and worked for thirty years, he was well thought of. Reports of his passing couldn’t help but mention his colour, but didn’t automatically doubt his character because of it.

Albert August Messiah, 60 years, died at his home, 85 Reservoir-street, Sydney, yesterday morning. A full-blooded negro from the West Indies, he has been known for 30 years as a chiropodist in Sydney and was well-liked by thousands whom he had attended. Messiah was once heard to remark that he had treated the corns on the feet of Sydney.

Sun (Sydney) 5 March 1916