Contemporary Accounts of the Crew Members.

The voyage of the Hopeful labour recruiting vessel from May to July 1884 ended with criminal charges and death sentences (quickly commuted) for several senior crew members. It was the first time that charges against people engaged in that traffic had “stuck,” and resulted in the kind of penalties that would have been incurred had the offences occurred on land.

The crew members charged always protested their innocence, and one died in custody. Five years later, due in no small part to partisan political agitation, a campaign of petitions for clemency caused an official review of the trials and their outcomes, and, eventually, the release of the prisoners.

There were questions raised about the presentation of evidence, but mainly, the issue boiled down to a foreign Black man, a wife-deserting carpenter, and several South Seas Islanders giving evidence against a group of mostly English white men. That, Queensland decided, was simply too much.

Chief Justice Lilley prepared a painstaking report, refuting all of the claims of the petitioners, and recommending that the crew remain in prison. The Governor ordered the men to be released in 1890.

From the evidence and statements at the trials, and in their release interviews with breathlessly excited reporters from the Courier and the Telegraph, we can extract some information about the natures of the men who crewed the Hopeful.

Captain Lewis Shaw

“Steward, if you want to be in this trade, you must be blind and see nothing.

Captain Shaw to Albert Messiah, when told of the shootings.[i]

“That prior to this serious charge of kidnapping, he was a young man of good behaviour, born of and nurtured by pious Christian parents, beloved by all who knew him and respected by all those who had intercourse with him.”[ii]

Petition for release, 1889.

Captain Lewis Shaw was born at Drainie, Moray, Scotland on 11 January 1860 to Lewis and Ann Shaw. He arrived in Queensland in charge of the Burns Philp & Co South Sea Island labour recruitment ship Hopeful in April 1884.

During the voyage that Shaw commanded, acts of murder and kidnapping were alleged to have taken place. While Shaw was not near or involved in the murders, he was in charge of a vessel where Islanders had been taken by force and deception.

In late August 1884, the cook and steward of the Hopeful, Albert Messiah, made a written statement of the events of the voyage, and gave it to Mr Philp of Burns Philp & Co, who summoned Captain Shaw to his office.

In Messiah’s evidence, the meeting is described in vivid detail.

Mr Philp handed the statement I had written to Captain Shaw. Captain Shaw read some portion of it. Captain Shaw asked me to come outside – he wanted to speak to me. I went out and he said, “We’ll go somewhere where we can have a quiet talk.” So, we went to the Post Office Hotel.

He said, “Steward I thought you’d be the last man to turn on me like this. Do you want me to shoot myself or hang myself or drown myself or what do you want?” He said, “Can I do anything for you? Can I square you with money?” When he said, “What do you want?” I said, “No, I don’t want you to shoot or hang or drown yourself. All I want is to let the affair be brought to the notice of the authorities.”

Although Shaw paid Messiah’s hotel expenses, handed him some money, ordered champagne, and helped get Messiah out of the next scheduled voyage of the Hopeful, Messiah persisted in his complaints to authorities. (Messiah admitted that he took the money, and drank the offered champagne, but felt compelled to report the matter further.)

Edward Dingwell, ship’s carpenter gave evidence that Shaw had offered him money and drinks to go and sign a paper refuting the allegations of improper recruiting. Dingwell refused both requests.[iii]

Shaw was arrested, tried, and was found guilty of kidnapping on 15 December 1884. Chief Justice Charles Lilley sentenced him thus:

“Lewis Shaw: Shortly stated, your crime is this: You received men captives from the hands of a murderer, stained with the blood of a treacherous and cruel murder done in furtherance of the crime of which you have been convicted, and this you did when you had been told that one of the companions of his captives had perished by his rifle.

And again, you sought to save yourself and your subordinates, and to pervert the course of justice, by bribing the witness who gave you this intelligence. For those things you must suffer the punishment next in degree to that of a murderer.[iv]

On entry into Brisbane Gaol, under sentence of imprisonment for life, Shaw’s background and identifying features were noted: Aged 25. 5 feet 8 ½ inches, proportionate build, dark complexion, brown hair and eyes. Reads and writes. Ship on breast. Epaulettes on each shoulder. Faith, hope and charity on right arm.

Lewis Shaw spent just over five years in gaol. He was first at Boggo Road, or the South Brisbane Gaol as it was called at the time, then at the St. Helena Island penal establishment. Shaw didn’t take to imprisonment well, and the Governor of St. Helena decided to return him to Brisbane after a series of breaches and punishments.

At the end of 1889, a public campaign to free the Hopeful prisoners was brought to the attention of the Government, and inquiries were made about the sentences and the behaviour of the prisoners, with a view to calming the populace by releasing the men.

R.J. Lewis, the Gaoler at South Brisbane, was concerned at the effect the incarceration was having on Shaw.[v]

“With regard to the conduct of Lewis Shaw, who has only lately arrived from St. Helena where his conduct had been ‘indifferent,’ I have to report that I think is mind is giving way. I have brought this to the Sheriff’s notice. He (Shaw) prefers to mope in his cell all day, apparently brooding over something. So, I have not interfered with him much, although some complaints have been made against him.”

Captain Pennefather, who oversaw St. Helena, reported on Shaw’s conduct on similar lines:

“He has been idle and stubborn and there has been considerable difficulty in getting him to conform to the regulations. At the same time, I do not think this man has either the mental or physical stamina of the other four and his spirits appeared to have become broken. While here he received the news of the sudden death of his father and mother within a few hours of each other and this appeared still more to make him lose heart.”[vi]

In February 1889, Shaw and the other Hopeful prisoners were released from custody by order of the Governor. To a man, they felt that their convictions and sentences had been grossly unfair.

Having tracked the captain down for an interview, the Courier[vii] waxed florid:

“When Lewis Shaw, the captain of the Hopeful was sentenced to imprisonment for life, he was a fine strapping fellow, about 23 years of age, and weighing 13 st. 8lb. When he was released yesterday, he weighed 9st. 2lb.

“As the time passed, he felt that all his chances of earthly happiness were dissipated, and although he still trusted in his promised Bride, he knew that to hold her to her word would be unmanly, and his misery was complete. What, then, were the feelings of this man to find on his release yesterday that the woman whose love he had won still waited for him, and was there to welcome him as only a faithful woman could? Shaw said last evening that the change in his condition was too much for him. He felt that it was only another of the many happy dreams that he had experienced, and he dreaded an awaking to the old terrible reality the daily routine of a convict’s life.”

In July 1892, he married Miss Louisa Dredge in Sydney. Presumably, Miss Dredge, who wore “a costume of white cashmere relieved by chiffon,” [viii] was the faithful “woman whose love he had won” all those years ago.

Shaw went on to take command of the British barque William Fairbairn on its voyage from England to Australia and experienced a rather memorable visit to the port of Melbourne in 1894. A drunken fight broke out between three sailors, and knives and belaying pins were produced. Two men ended up in hospital. Then a mass outbreak of insubordination occurred when Shaw ordered a watch change that would see some of his crew under the charge of a particularly loathed boatswain. Both matters ended up before the Magistrates Court.[ix]

Captain Shaw seems to have continued his maritime career for two more decades, appearing on crew lists into the 1910s.

Neil McNeil, Second Officer and Recruiting Agent

“Drop the bugger.”

Neil McNeil, ordering his boat’s crew to fire on an islander in a canoe.[x]

“Before and since the time of the alleged murder, the said Neil McNeil has been known at Townsville as a respectable man.”

Petition for clemency.[xi]

Neil McNeil was born at Calton, Glasgow, Lanark, Scotland to Neil McNeil and Mary Archibald McNeil on April 1, 1862. He arrived in the colony of Queensland with the Hopeful in early 1884, and was Second Officer and Recruiting Agent on the voyage to New Guinea that commenced in April 1884.

McNeil was in the first longboat that went out to meet the canoes carrying inhabitants of Sanaroa. He had been speared in the leg not long before in a scuffle, which may well have hardened his attitude to the men he was supposed to be recruiting. When one man in a canoe used his paddle to fend off McNeil’s men, he ordered them to “Drop the bugger.” A shot was fired but missed. McNeil then shouldered his rifle and shot the man in the chest from a distance of about five yards. The islander fell and never moved again.

Neil McNeil was arrested, tried, found guilty, and sentenced for murder and kidnapping. His death sentence caused a sensation at the time. It was the first time a labour recruiter had been found guilty of murdering a recruit, after years of dark rumour and failed trials over the Pacific Island labour trade.

Even McNeil’s arrest caused headlines. The Figaro was appalled at the way he was taken into custody: (The officer) took McNeil away, the prisoner being dressed only in his cotton singlet and trousers. The constable would not even let McNeil put on his boots or coat.[xii]

Terrible.

Chief Justice Lilley said:

“Neil McNeil, it is very pitiable indeed to see so young a man as you, just in the very flush of life, standing convicted of so serious an offence. The jury in the discharge of their painful duty have found you guilty upon evidence which, I am bound to say, satisfies to my mind the requirements of the law. I will not say anything that can possibly give you more pain that you probably experience at the present moment. Unhappily, it is to be feared that yours is not the only case of outrage upon these unhappy creatures in the South Sea Islands.

The law has appointed me a duty which has in no way left me any discretion but to pronounce upon you the sentence of death. The sentence of the court is that you be taken hence to the place from which you came, and at such time and place as the Governor-in-Council shall order, you shall be hanged by the neck until you are dead, and may the Lord have mercy upon your soul.”

The prisoner, who had watched the case with keen interest throughout, was visibly affected when his Honour pronounced sentence. As he left the dock a deadly pallor overspread his features.[xiii]

The Admission Register for the Brisbane Gaol recorded its new prisoner: Neil McNeil, Sailor, aged 27. 5 feet 11 inches, proportionate build. Ruddy complexion, light (brown) hair, Grey eyes. Reads and writes. Spear mark on left thigh.[xiv]

Petitions for clemency flew back and forth throughout the colony in response to the sentence, and McNeil’s death penalty was remitted to life imprisonment before the month ended.

During his time in Brisbane Gaol (1884-1888) and St Helena Penal Establishment (1888-1890), Neil McNeil was a model prisoner – “hardworking, willing and obedient.”

On his release in February 1890, McNeil gave an interview on his arrival back in Brisbane from St Helena Island. The Telegraph’s account gave the impression of a taciturn man who had been through what he felt was an unjust sentence, and had no immediate plans:

McNeil said, he had always thought he would be released sooner or later. This conviction had settled upon him from a consciousness of innocence of the crime with which he had been charged. The conviction was ever a bright ray shining into his monotonous round of everyday life and serve to cheer to no little extent the prospect of confinement while life lasted. [xv]

Neil McNeil had less than a year to enjoy his release from prison. On January 1, 1891, he collapsed during a heatwave in Townsville and passed away from heat apoplexy. He was just shy of his 29th birthday.

Bernard or Barnard Williams, Mate and boat crew

“You son of a bitch, if you don’t come back, I’ll shoot you.”

Bernard Williams

“Don’t shoot the poor bastard.”

Albert Messiah to Bernard Williams.[xvi].

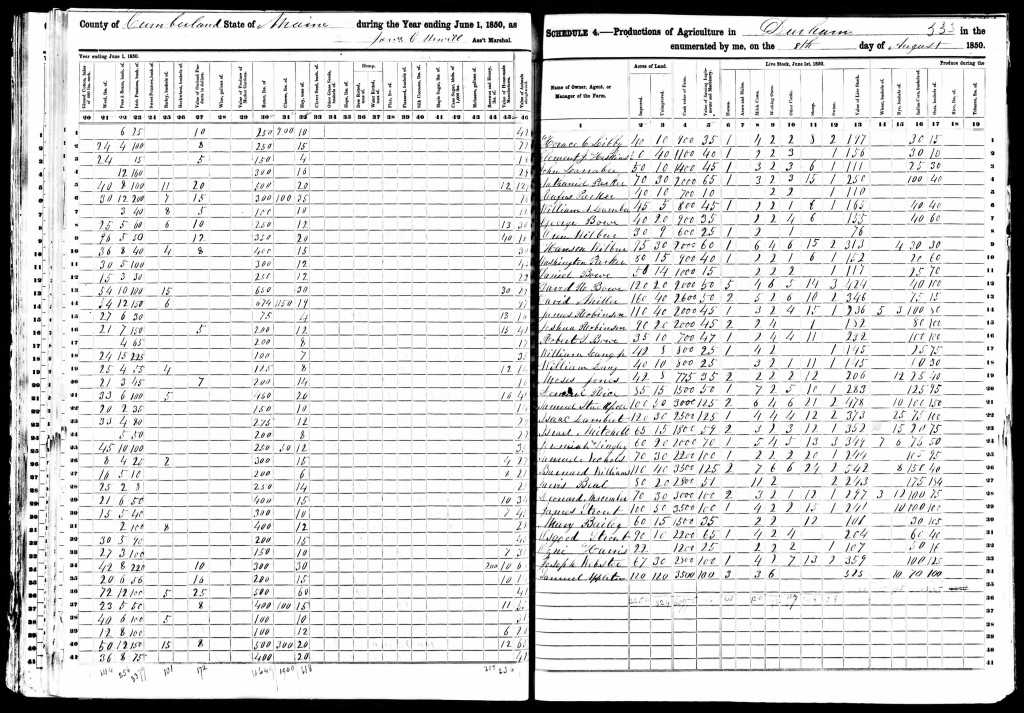

The correct details of the life of Barnard or Bernard Williams can be hard to pin down. By his own account, given on two occasions, he was born in Portland, Maine, United States of America around 1853. His father was a respectable farmer in that place, and he had been at sea since 1870.

Bernard Williams (the name I’m using for convenience – he was charged as Bernard) was known as Barney. There was a Barnard Williams who owned land and farmed in the district for decades, presumably Barney Senior. [xvii] That Barnard Williams had been born in Maine in the early 1830s, and was still alive, and the head of a large family, at the time of his son’s legal trouble in a far-away colony.

Barney Williams had been at sea for more than a decade when he came to the colony of Queensland with the Hopeful. During the recruitment voyage, Williams was said to have shot at an islander who had jumped from a canoe and was swimming away. “He put the Snider to his shoulder and fired while the boy was swimming. Where the boy was swimming became all bloody. The boy disappeared and went down.” The islander appeared to have had part of his skull blown off by the bullet, and never resurfaced.[xviii]

Barney Williams was charged, tried, and found guilty of murder and kidnapping. He was stolid in the face of a death sentence, and proved to be an industrious, well-behaved prisoner at Brisbane and St. Helena.

The Prisoner, on being asked if he had anything to say why sentence of death should not be passed on him, said that all he had to say was that Messiah’s evidence was utterly false, and that he had sworn to an act he never saw. The Chief Justice, addressing the prisoner, said that he concurred entirely in the verdict of the jury. He would convey the recommendation to the council; but he could make no promise that he would support that recommendation by any of his own. His Honour then passed the death sentence in the usual way. The prisoner, who had been manifesting the utmost calmness during the whole of the day’s proceedings, exhibited no change of demeanour on hearing his sentence, but quietly left the dock. He even turned round before putting his hat on to see that His Honour had left the court, and, finding he had not, went down the steps uncovered.[xix]

Brisbane Gaol received a man who was in his late 20s, 5 feet 4 ¼ inches, slightly built, with a dark complexion, brown hair, and grey eyes. He was able to read and write. He sported the tattoos typical of a seaman: B.G. Williams with flag on right arm and a star on right wrist. 1854 with a flag and eagle on left arm.[xx]

There was so little known about Williams in Queensland that the petitions for clemency could not offer any insights into his character, focusing instead on the nature of the evidence presented against him.

On release in 1890, Barney Williams was reluctant to make any comment on his troubles. He would think things over and write a statement for publication in due course.

A small man in stature, he seemed wiry and active, though prematurely aged. The severity of his sentence had evidently told upon him a good deal, and while it had tinged his hair with grey had also enfeebled his frame a little. He made no complaint and said he had been treated just as any other prisoner had been. He said he was 36 years of age, and had been at sea, except during the term of his imprisonment, from 1870. He was born in Portland, State of Maine, United States, where his father was a farmer held in general respect.[xxi]

And with that, he disappeared from the public view in Australia. A search of newspapers does not reveal a public statement about the Hopeful. A lifelong sailor, he seems to have just gone on his way.

Thomas Freeman, First Mate

“I was charged at the trial, I believe, only as an accessory, my offence being my failure to record certain events of the voyage in the ship’s official log.”

Thomas Freeman, interview 1890.

(John) Thomas Freeman was born in Nottinghamshire in 1856 and was certified as a mate in 1881. After emigrating to Australia and managing to be aboard two ships that were destroyed, he signed on to the Burns Philp labour vessel Hopeful.

On the day of the murders, recalled by prosecution witness Albert Messiah as June 13, 1884, Freeman was not on the recruiting boats. He had remained on board the Hopeful as second in command. He was well aware of what was happening, though, and prosecution evidence showed that fired a shot in the direction of one of the canoes when the scuffle with the islanders broke out.

Thomas Freeman was charged with, and convicted of, kidnapping islanders. He received a sentence of ten years’ penal servitude.

Thomas Freeman. You were an inferior agent, but still a ship’s officer, and you fired on the canoe. You could not be ignorant of many of the other misdeeds on this voyage of the Hopeful, and you came here and, as I believe, perjured yourself to serve your shipmates and yourself. I have favourably regarded the merciful recommendation of the jurors. The sentence of the court is that you be kept in penal servitude for ten years, the first two years in irons. Chief Justice Lilley [xxii]

On arrival at Brisbane Gaol, he was 28 years of age, stood 5 feet 6 inches and was of a stout build. His complexion was dark, with dark brown hair and brown eyes. He was able to read and write and had two flags and an anchor tattooed on his right arm.[xxiii]

Unlike his shipmates, Freeman remained in Brisbane Gaol at his own request. His sisters lived in Brisbane and could visit him there. He was entrusted with administrative duties such as cell allocation, at the Gaol. He was a model prisoner and had earned remissions on his sentence for good behaviour.

On release, Freeman was a loquacious interviewee. He expressed sorrow at the deterioration and death of Harry Schofield, shock at the growth of Brisbane in just five years, and hesitation about his future plans. He recounted the loss of the Jemima on a reef, and the Duke of Richmond in a cyclone. He had gone straight from these vessels to the Hopeful. Despite the ill-fated voyages he’d been on, he thought he might just go to sea again. This turned out to be a very bad idea.[xxiv]

Thomas Freeman married Jessie Ellen Willis on 12 November 1890. Jessie, like Louisa Shaw, had waited for him while he was in prison. They had two children -Thomas Everard Freeman in 1891 and Flora Freeman in 1894.[xxv]

Thomas Freeman returned to work with Burns Philp & Co and became a Master Mariner and captain. On 29 November 1898, Captain Thomas Freeman disappeared from the deck of the Wakefield near Cape Cleveland at Townsville. He had navigated the vessel out of Barratta Creek, then handed her over to his mate. He had been in good spirits that day and was last seen on deck near his cabin. No trace of him was ever found, and it was assumed that he had slipped, fallen overboard, and drowned.[xxvi]

Edward Rogers, Able Seaman and boat crew

“Really, I can’t say what the object was, perhaps that they should make fun of us; and I would not like to say that they tried to make fun of us for poor beggars they know no better.”

Edward Rogers, on the visit of the kidnapped islanders to the Gaol. interview 1890

Edward Joseph Freeman Rogers was born on 21 September 1865 in Dublin, Ireland to John Rogers and Isabella Freeman, one of eight children. He was a couple of years younger than he claimed to be in his various articles of employment and marriage certificates.[xxvii]

On the day of the Hopeful murders, Rogers was in the recruiting boat with Neil McNeil. Rogers was armed with a Snider rife and an ammunition pouch but did not use them. He and James Preston held on to one of the islanders’ canoes from the recruiting boat.

Rogers was arrested at a boarding house in George Street, together with Freeman, by Detective Grimshaw. He was convicted of kidnapping and sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude, the first year to be spent in irons.

James Preston, Edward Rogers. You were seamen who, it seems, can be hired to share in these evil courses. I have, however, given effect to the merciful feeling of the jurors and the sentence of the court is that you, and each of you, be kept in penal servitude for seven years, the first year in irons. Chief Justice Lilley.[xxviii]

On his admission to Brisbane Gaol he said he was 25 years of age but was more likely 20. He stood 5 feet 10 ½ inches. He was of proportionate build, with a sallow complexion, auburn hair and brown eyes. He could read and write and had tattoos of a female and flag on his left arm. His right arm was tattooed with “faith, hope and charity.” [xxix]

Rogers had a spotless prison record, both in Brisbane Gaol and at St. Helena Island. He was young and industrious and was interested in learning a trade.

When he emerged from custody in 1890, he was 25 rather than the stated 30 years of age, and a very willing interviewee. He told the Courier of the day that Sir Samuel Griffith came to see the governor of the gaol, and how the governor pointed out the Hopeful prisoners. They were, he believed, being measured for ‘shot drill,’ a particularly loathed form of punishment.[1]

Rogers felt that the Hopeful men were spared shot drill because of the adverse publicity surrounding a visit arranged for the kidnapped islanders to view the Hopeful prisoners in custody, shortly after the verdicts. Or, as Rogers put it, “the time the n****rs were sent up to see us.” [xxx]

In 1892, Edward Joseph Freeman Rogers married one Ellen Ferguson at Maryborough in Queensland.[xxxi] Their union was a curious one.

Ellen Ferguson nee Hanna was a widow, originally from County Down in Ireland, who stated on the marriage certificate that she was 37 years old. She had previously been married in Ireland in 1864, to John Ferguson. Later that year, the Fergusons emigrated to Queensland, where their daughter Ellen was born in 1867. John Ferguson died aged 45 in November 1891. Five months later, Mrs Ferguson became Mrs Rogers.

If Ellen really was 37 in 1892, she must have married Mr Ferguson when she was nine years old. Other research puts her date of birth around 1842, making the bride a presumably youthful-looking woman of 50. Edward Rogers politely added a few years to his actual age of 27, claiming to be 32.

The union was not blessed with issue during their time in Queensland and does not appear to have been a happy one. Indeed, in 1901, Edward J.F. Rogers was the subject of a New South Wales police arrest warrant on a charge of wife desertion, issued by Ellen Rogers, of Clarence-lane. The charge was subsequently withdrawn, but not before Ned was put in handcuffs. (He was described as 5 feet 10 inches, and “42 (looks younger)”.[xxxii] No wonder. He was around 36.

Ellen Hanna Ferguson Rogers died aged 60 in September 1907[xxxiii], freeing her estranged husband to marry Phoebe Pearl Axam,[xxxiv] who, at 24 years of age, was born the year her husband sailed in the Hopeful. They had a daughter, Isabella Laura Rogers[xxxv], in 1909, and Phoebe passed away in July 1910. [xxxvi] Edward Joseph Freeman Rogers died in Sydney on December 30, 1925, aged 60.[xxxvii]

James Preston, Able Seaman

“He was quite unfamiliar with the labour trade, but says that he saw neither violence nor inhumanity displayed to the islanders on the memorable cruise of the Hopeful.”

Interview on release from prison.

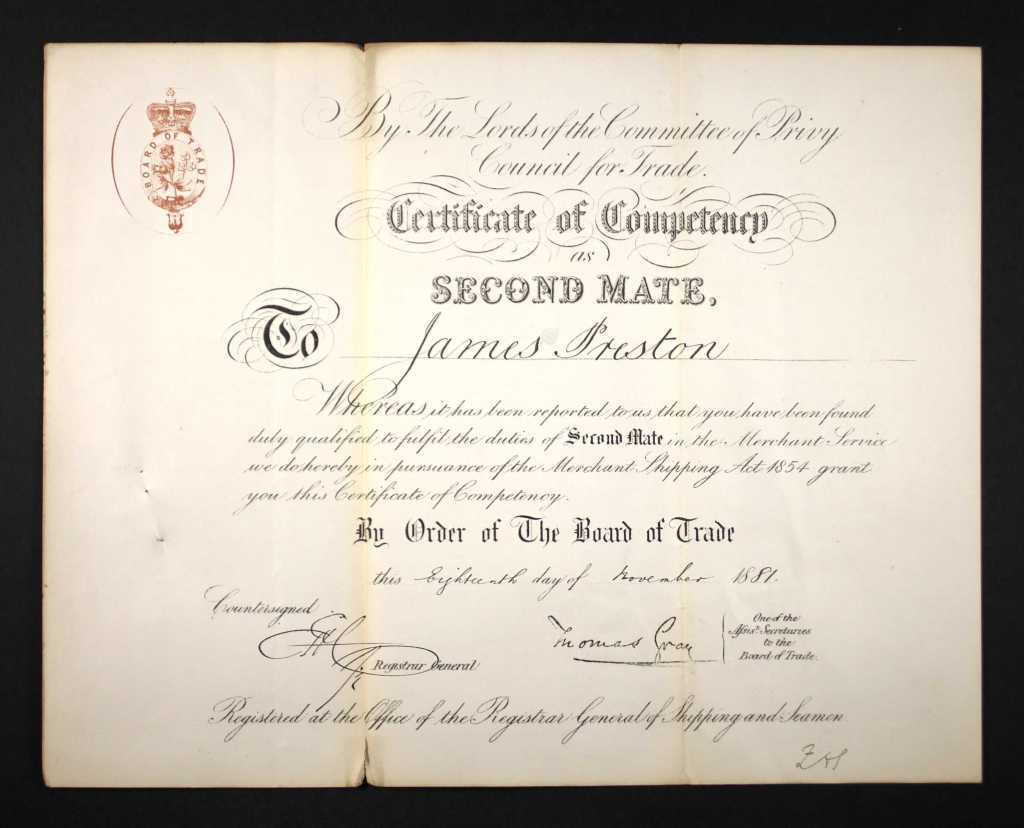

James Preston was born on 19 April 1860 in Aberdeen to James and Isabella Preston.[xxxviii] He was baby number five for that couple. James Senior worked as a carpenter and shipwright.

Preston gained a certification of competency as Second Mate from the Board of Trade in 1881[xxxix], and that year went out to Queensland via the Scottish Lassie to work with Thomas Freeman in the coasting trade. He was boatswain to Freeman in the Jemima, which came to grief, causing Freeman and Rogers to sign up for the labour trade with the Hopeful.

On the voyage to the New Guinea islands, Preston was on board the recruiting boat with Neil McNeil, and shouldered his Snider rifle when Neil called out, “Drop the bugger!” Preston did not fire. He also held on to one of the islanders’ canoes, together with Edward Rogers.[xl]

Preston had come to Brisbane to give evidence in support of McNeil, Williams and Schofield, and was staying at a boarding house in Albert Street when the police came to arrest him for kidnapping.

He was tried and found guilty of kidnapping and was sentenced to seven years penal servitude, the first year in irons. When he arrived in Brisbane Gaol, aged 24, he was described as 5 feet 6 ½ inches, with a proportionate build, a dark complexion, light brown hair and grey eyes. He had a bracelet tattooed on each wrist, and a star on his right hand.[xli]

During his incarceration at Brisbane, and later at St Helena Island, Preston worked in the carpentry shop, and was hammering away industriously when word came of his release in 1890. He had a couple of minor disciplinary issues while on the island – he disrespected a warder, had a pipe at muster, and conducted himself in a disorderly manner one May evening at 7:45 pm. And then continued being disorderly when told to stop it. He got off with a telling-off.[xlii]

On his release, he gave little information about himself and his time in prison. He remembered the visit of the islanders in December 1884, mentioned the ill-luck that led him to joining the Hopeful, and reiterated his innocence and that of his comrades. No cheeky Ned Rogers or Thomas Freeman quotes for the papers, just a desire to get away from everything that had happened.[xliii]

James Preston returned to the seas, gaining a certificate of competency from Board of Trade as a First Mate in 1892.[xliv] His name appears in various ship manifests. I suspect he may be the James Preston (retired ship’s carpenter) who was listed in the Scotland Will Index in 1923, because it seems too late a date for it to be his father.

George Tulloch, Able Seaman and Sails

“I never saw kanakas recruited from canoes.”

George Tulloch, 1884, Crown Law notes.

George Tulloch was born about 1849 in Scotland and shipped out from Liverpool in 1882. He worked the coastal schooner trade and was on board the Silvery Wave in early 1884. This boat was dismasted in the same cyclone that wrecked the Jemima. Like the equally shipless Preston and Freeman, he took a job (as sailmaker) on the Hopeful labour schooner in April 1884.

Tulloch was not charged with any offence in the aftermath of the voyage. His presence on the journey is only alluded to in evidence as being one of the white crew members. He appears to have taken no part in the recruiting activities.[xlv]

Tulloch was interviewed by Crown Law officers before the trial. He denied anything irregular had taken place and was not called by either the prosecution or defence at the trials. This issue was taken up as a cause celebre when the review into the Hopeful convictions was taking place in late 1889.

Minister for Justice, A.J. Thynne, decided that the notes of interview taken in 1884 by Crown Law “show that these three men would have exculpated the prisoners.”[xlvi]

These notes have survived, and hardly seem to be the smoking gun Mr Thynne claimed:

GEORGE TULLOCH, “Sails,” Hopeful.

I never saw kanakas recruited from canoes. About 4:40 pm on Saturday, about four weeks next Saturday, Mr Norris, solicitor of Townsville, was on board the “Juventa”; I think Captain Shaw took me down into the cabin; he asked me to give him a statement as to the voyage of the Hopeful; I have him a statement to the effect that I had seen nothing wrong; he took my statement down in writing; I signed it, I think.[xlvii]

That’s it. Hardly a ringing endorsement for the defence – “I didn’t see anything.” Tulloch was approached by Captain Shaw for his statement whilst aboard another notorious recruitment vessel, the Juventa. The voyage of the Hopeful had not put him off labour recruitment.

George Tulloch next appears in Sydney in 1885, receiving a month in prison for disobedience of orders on board the Kent. After that, he seems to have left the colonies for once and for all.

Charles Siebert (Charlie the German), Able Seaman

“I have seen McNeil and Williams bring kanakas on board; never saw where they got them from.”

Charles Siebert, Crown Law notes, 1884.

Charles Siebert, or Charlie the German as he was called, was born in Germany in 1852.[xlviii] He had been on the labour recruitment vessel the Lizzie before joining the Hopeful in 1884. Inquiries and court cases surrounding the Lizzie, and the trade generally, often refer to a Charlie the German, albeit in passing.

Siebert had been in Queensland for a while prior to the Hopeful, and had married Elizabeth Watt Cumming in November 1883, shipping out before the ink on the certificate was dry.[xlix]

Charles Siebert’s evidence was also taken by Crown Law, but not required in Court, and the notes of this were seized on by Mr Thynne in a similar way to Tulloch’s.

CHARLES SIEBERT, A.B. ON BOARD THE HOPEFUL. MASTER – SHAW.

Don’t remember 10th June or 13th June; don’t remember where I then was; I was on that day on the Hopeful; she was somewhere off the coasts of New Guinea; I have been about sixteen years at sea; have seen McNeil go in the ship’s boats with firearms – snider and a revolver; couldn’t tell whether they were loaded or not; have also seen Williams; have seen McNeil and Williams and some of the ship’s crew firing at targets; never at anything else; never saw them hit the targets; they have gone near them; have seen McNeil and Williams bring kanakas on board; never saw where they got them from; I have been three voyages to South Sea Islands; only once to New Guinea islands; I saw Captain Shaw in Townsville; I remember a day in last August; young Mr Norris met me in the street in Townsville at about 5 o’clock in the afternoon; he asked me to go with him on board the “Juventa”; I went; he asked me if I went in the boats, if I had seen any kidnapping going on, if I had seen anyone shot; he took may answers down in writing; my answers were “no”‘ he then asked me to sign the paper; I signed the paper; never received anything from Captain Saw except my pay; did not receive anything from Norris.[l]

Charles Siebert’s statement is a little more detailed, but again, he “never saw” anything. Siebert could have been called by either side in the trials, and the opportunity for cross-examination was there, but was not taken up.

Siebert chose to become naturalised shortly after his visit from young Mr Norris (a solicitor for Burns, Philp & Co). At the same time and place as Albert Messiah – September 1, 1884, at Townsville.

Charles Siebert apparently never returned to Elizabeth Cumming Siebert after shipping out. In 1894, the residents of North Queensland were entertained by the proceedings brought by his spurned bride, some eleven years after the wedding:

Siebert v. Siebert. Extraordinary Revelations. Townsville. May 20.

In the Supreme, Court yesterday, Mr. Justice Cooper tried the divorce suit Siebert v. Siebert, in which the wife petitioned for a divorce on the grounds of adultery and desertion. The evidence went to show that the parties were married on the evening of November 17, 1883. They then went to a friend’s house where festivities were kept up until 7 o’clock next morning. The next night the wife slept with the mistress of the house, and her husband, who is a sailor, in the front room. The next morning at 5 o’clock he left to join his ship, which was a labour vessel. He was away six months, and on his return did not provide his wife with a home. She remained in domestic service, and the marriage was never consummated.

Subsequently the husband was found to be living in Melbourne with a woman who had three children, and was recently proved to be living in Maryborough with the same woman who then had three children. A decree nisi was granted, returnable in three months.[li]

Charles Siebert married Margaret Sellyer, presumably the other woman in the marriage, as soon as it was legally possible to do so. [lii] Good thing too, because William Henry Siebert was born less than two months afterwards. Charlotte Lillian followed in 1897. Charles Siebert died in Sydney in 1935, and is buried in Rookwood General Cemetery.

Samuel Binns, Able Seaman and boat crew

“(There) could not have been any shooting or kidnapping within 30 yards of the ship without my seeing or hearing it.”

Samuel Binns, 1884

Samuel Binns was born in Jamaica in 1841, according to the Crew Lists of the Hopeful. Little more can be discovered about him, beyond the fact that he was a white man, and gave a statement to Crown Law in 1884. He was not called for the prosecution or defence, and the fact that there were three white men who hadn’t been called as witnesses led to rumours that their evidence was excluded by a prosecution anxious to follow a Government’s anti-labour policy. Here is Samuel Binns’s statement to Crown Law:

SAMUEL BINNS, Boat’s Crew and A.B. on board the Hopeful.

On 24th May McNeil and myself had a row; McNeil struck me on the left jaw; struck me because I growled about having to pull the boat; signed a paper in Townsville to the effect that I had not seen anything wrong done; could not have been any shooting or kidnapping within 30 yards of the ship without my seeing or hearing it. [liii]

In his response to the review of the Hopeful convictions, Chief Justice Lilley opined that the statements of Binns, Tulloch and Siebert added nothing to the evidence before the Court. He theorised that the men were not called for the defence because their testimony might not have withstood cross-examination.[liv]

On March 1, 1889, Samuel Binns was again on a labour vessel, this time the Northern Belle, which was recruiting in Vanuatu when a cyclone struck. He was one of the twenty people who drowned.

WRECK OF THE SCHOONER NORTHERN BELLE. FOUR WHITES AND SIXTEEN KANAKAS DROWNED.

While anchored off Motlab on the night of the 27th February a hurricane came on, and the following morning she drifted on the rocks with tremendous force, and almost immediately foundered. A scene of the wildest confusion ensued, several of the crew being swept overboard, but the majority managed to cling to the rigging and portions of the wreckage, and were washed ashore in an exhausted condition. Captain Spence was the last to reach the shore, and he had his right arm badly lacerated through contact with a coral reef. Benjamin James the mate, and Samuel Binns, William Nielsen, and A. Johnson, able seamen, and 16 kanakas were drowned. [lv]

Henry Schofield, Government Agent

“The Government Agent was on the aft poop and seemed intoxicated.”

Edward Dingwell, at the committal hearing, 6 October 1884.

“His constitution was utterly wrecked long before he went into the labour trolley but the imprisonment, and the irons he had to wear, no doubt greatly accelerated his death.”

Thomas Freeman, interviewed in 1890

“Harry Schofield was a man of good birth and education and if he had one fault more than another it lay in the possession of a comprehensive and superabundant good nature.”

“HFW,” 1914.[lvi]

Henry Schofield was born in Manchester, England around 1850.[lvii] There were quite a few Henry Schofields born and christened in Lancashire around 1850, and I think that the most likely family is that of James and Alice Schofield.[lviii] Their Henry was born on 16 December 1850, the sixth child to that family. I have no proof of this theory, but the few people who seemed to know Schofield suggest that he had a large family there.

He came to Queensland as a teenager, aboard the Ocean Empress in 1866, and attracted no public notice until 1884 when he took on the role of Government Agent aboard the Hopeful. He seems to have had a drinking problem for some time, and the effects of the alcohol or the medicine he took ravaged his health.

When arrested and charged with kidnapping, he was brought before the Townsville Magistrate, who reprimanded him for being drunk.[lix] He stated that he was ill, and had been ill, not drunk, on the day of the shootings, which he said didn’t happen. He gave contradictory evidence about the accuracy of his logbook and appeared to be completely out of his depth in the role of Government Agent. He had, he said, “only come out of the bush four days before he sailed,” and knew nothing of the labour trade. He was sentenced to penal servitude for life, the first three years in irons.[lx]

Harry Schofield – The jury did not recommend you to mercy. You were the Government agent, and you never once asserted your authority for the protection of the natives from these outrages. On the contrary, corrupted either by drink or other influence, you permitted them to be fired upon on more than one occasion, and once for a considerable time; you omitted the record of two murders from your log; you witnessed the destruction of a canoe which had been fired on by one of the ship’s officers and the capture of the natives who had attempted to escape to their homes by swimming. You, moreover, as I believe, came here and perjured yourself to save the companions of your guilt, and perchance to save yourself. It is not possible, nor is it desirable, that we should withdraw our view from the whole of your conduct in weighing the gravity of your offence. You were trusted to protect the islanders and to prevent these crimes. When you participated in them the law was disarmed, and crime had nearly triumphed. It was said in old times, “the gods must have feet of wool,” and it is said by men of modern times that Divine justice silently and unexpectedly overtakes the guilty. The things you thought you had hidden – deep buried -dead – have risen in judgment against you. The sentences of the court is that you be kept in penal servitude for life, the first three years in irons. Chief Justice Lilley.[lxi]

On arrival at Brisbane Goal, he was described as 34 years of age, 5 feet 8 ½ inches, and of proportionate build. He had a fair complexion, and brown hair and eye, and was literate.[lxii]

Schofield had been ill during his remand time, and remained unwell, with what were described as bladder and kidney problems, throughout 1885. He received medical attention at the gaol, and was hospitalised in late December 1885, suffering from constant urinary incontinence. He remained in irons throughout his illness and hospitalisation, and died after suffering a seizure on the night of 18 January 1886.

A coronial inquest was held at the gaol, attesting to the misery Schofield had undergone with his illness, and the final seizure that took his life. The focus of the inquest seemed not to be the cause of his death but excluding the possibility that his irons contributed in any way to his demise. Every witness examined mentions his irons, and how they had no effect whatever on his health. It cannot have been comfortable to be in irons on one’s deathbed, though.[lxiii]

Nevertheless, there was a press outcry when it was revealed that he died in his chains. “Hobbled to Death,” read one headline.[lxiv] He is buried in an unmarked grave, plot 70, at the South Brisbane Cemetery.[lxv]

Edward Dingwall or Dingwell, Carpenter

“I saw no attempt made to explain the nature of any agreement to four the boys we brought onboard when they were sent below. I don’t call it recruiting.”

Edward Dingwell, evidence at the committal hearing, 6 October 1884. [lxvi]

“I was living in the Towers before I shipped in the Hopeful – Charters Towers. I did not desert my wife and family there.”

lxvii

Edward Dingwell (that seems to be the preferred spelling in official documents) was forty when he signed up to be the carpenter on board the Hopeful in 1884.[lxviii] He was born in Portland, Maine, USA – the very same place that Barnard Williams called home – in about 1840. Could they have known each other? There are no references to any form of familiarity between the men in any document I can find.

Dingwell arrived in New South Wales, a free immigrant, on the South Carolina in 1857. He seems to have led a jobbing life, working as a carpenter before getting into a spot of difficulty over a horse of disputed ownership in 1866.[lxix]

As a result of the dispute, he received two years’ hard labour from the Wagga Wagga Bench in 1866, but was well-behaved in custody, and received an early release in 1867.[lxx]

In February 1876, Edward Dingwell married Elizabeth Kavanagh or Cavanagh at Springsure in Queensland. [lxxi] The couple started a family, of whom we have records for George Henry Dingwell in 1880 and Adelaide Amanda Dingwell in 1882. (They seem to have had four children in all.)

The Dingwells were not a happy couple. Edward liked a drink. Elizabeth liked to have food on the table. In October 1882, she had had enough, and Edward was arrested for leaving his family without means of support in Charters Towers.

Elizabeth Dingwell testified that she had been unable to purchase food and necessities on credit because Edward had been seen about the place drinking. Furthermore, she was heavily pregnant and was likely to be thrown out of her accommodation. Edward Dingwell countered that she had physically attacked him. She denied it. The Bench, sensing that this was getting nowhere, asked Mrs Dingwell how much her husband could earn. She deposed that he was a bridge carpenter and could earn £12 and £14 a month.

Edward Dingwell made a generous offer that he would support his children, but not his wife. The Bench ordered a schedule of payments and sureties, and Dingwell asked nicely if he could go to gaol for six months instead. The Bench made it clear that whether he went to gaol was entirely up to him.[lxxii]

Dingwell signed on for the Hopeful in 1884 and supplied evidence for the Crown that broadly supported that of Albert Messiah. He also described Lewis Shaw offering him money to sign a statement exonerating the Hopeful and her crew from charges of kidnapping and murder. He refused.[lxxiii] He had initially refused to say anything to the authorities, but later gave a statement that broadly support the allegations made by Messiah.

When it came time to try the case, in Brisbane in December 1884, Edward Dingwell’s shambolic family finances were used against him in cross-examination. He admitted that he had been negligent with paying his wife money from time to time but had not left her without funds while he went to sea. In fact, he said, he had spent time with his family before his departure, and had arranged a line of credit for Elizabeth through his wages.[lxxiv]

Chief Justice Lilley, writing a review of the case in answer to petitions, five years later, stated that:

Dingwell was an unwilling witness to the last. He pressed nothing against the prisoners. His evidence impressed me as that of a man who was speaking the truth, but with a feeling that he would rather have had no part in testifying. It must be remembered that in giving evidence he was bearing witness against his mates, the owner of the ship, his prospect of employment, and his own interest and feeling. He showed not the least feeling against the prisoners, but the contrary. [lxxv]

After the trials, Edward Dingwell disappears from the records – it was a common enough name – although there was a carpenter of that name resident in Alexandria, Sydney in 1887.[lxxvi]

Albert Messiah, Cook and Steward

“Messiah, my name, can be traced 100 years back in the West Indies. My ancestors were brought from Africa.”[lxxvii]

Albert Messiah’s life was covered in a separate blog post “The Witness for the Prosecution.” He was a perplexing figure – a man who was considered a cheat and a liar, who was also a beloved father and well-loved Sydney character. In Court, he quoted Shakespeare to a no doubt irritated Charles Chubb, QC. He didn’t shrink from taking money from Captain Shaw, but the events of the journey troubled his conscience.

Albert Messiah had been born in Antigua in the 1840s. As a descendent of people who had been taken from Africa to work on sugar plantations, he would surely have known the intent of these labour recruitment schemes in Queensland. They’d been operating for two decades. Yet he was a Black man who was willing to work on labour schooners. But also willing to draw the line at murder and kidnapping.

Toarong

Toarong was sixteen years old when he joined the crew of the Hopeful. This appears to be his name as written on the crew manifests. He is listed as an interpreter. Because of the wildly divergent spelling employed by clerks, judges and journalists, it’s hard to track down his exact details. He does not appear to have given evidence.

Jack, Boat crew

Jack was 26 years of age, and a native of Aurora. He did not sign on for another voyage on the Hopeful after 1884. He was hired as boats crew, rather than as an interpreter.

Harry Dobo, Boat crew

Harry Dobo, 25, of Aboa, had previously been on the Lizzie. He too was boat crew, rather than an official interpreter.

Charlie, Boat crew

Charlie was 28, from Santo and was boat’s crew. He was one of the people in the boat crew who held on to the canoe at Sanaroa. The man who was subsequently murdered had hit Charlie on the arm with a paddle.

After the Hopeful voyage, Charlie worked on a plantation on the Albert River, and gave evidence at the trials in December 1884.

Recruited at Teste Island as crew during voyage

Naup, 24

Hired on at Teste Island as boat’s crew. His articles show that he deserted but do not say when.

Alix, 26

Was hired on as an interpreter at Teste Island. He also deserted. Referred to as “Alick” in the newspapers, he left the ship on her return to Teste Island.

Cargo, 20

“Cargo, I will buy you plenty things when we get to Burra Burra, and if big fellow ask you if we been shooting blackfellows you say no.”

Captain Lewis Shaw to Cargo.” [lxxviii]

Cargo was hired on as interpreter and boat’s crew. He made it to Townsville to collect his £2, 7 shillings and fourpence.

Cargo signed on for another voyage on the Hopeful, but instead came to Brisbane to do duty as a witness and interpreter.

The New Guinea natives who were alleged to have been kidnapped in the Hopeful, and who during the recent trials were lodged in Brisbane, left for the North in the Q.S.S. Co.’s steamer Maranoa on Saturday last. Some of them will be employed as interpreters by the Royal Commission. All of them will eventually be returned to their homes along with any others whom the Royal Commissioners may decide were improperly recruited.[lxxix]

[1] This punishment involved prisoners carrying a heavy iron cannonball at chest height for a certain distance, putting it down in a marked spot, and then picking up another to do the same thing. www.bodminjail.com

[i] Albert Messiah, The Hopeful Papers Part 1 – DR 112166 Queensland State Archives (QSA)

[ii] Petition of the residents of Brisbane to Sir Anthony Musgrave, Governor, received 31 May 1887. The Hopeful Papers Part 1 – DR 112166 (QSA)

[iii] Regina v Bernard Williams & Ors Oral Evidence. ITM 7868 (QSA)

[iv] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 15 December 1884, page 4.

[v] The Hopeful Papers Part 3 – DR 112168 (QSA)

[vi] The Hopeful Papers Part 3 – DR 112168 (QSA)

[vii] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Thursday 20 February 1890, page 5

[viii] National Advocate (Bathurst, NSW: 1889-1954), Mon 1 Aug 1892, Page 2.

[ix] Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), Tuesday 30 October 1894, page 6

[x] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 22 September 1884, page 5.

[xi] The Hopeful Papers Part 1 – DR112166, (QSA) Petition for clemency from the residents of Townsville

[xii] Queensland Figaro (Brisbane, Qld. : 1883 – 1885), Saturday 4 October 1884, page 4

[xiii] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Friday 28 November 1884, page 5

[xiv] Register of Prisoners Brisbane Gaol 1879-1889 DR 91652. (QSA)

[xv] The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872-1947), Thu 20 Feb 1890, page 4.

[xvi] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Tuesday 2 December 1884, page 5.

[xvii] Portland Daily Press, 1851 and Monday May 28, 1866.

[xviii] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Wednesday 3 December 1884, page 5.

[xix] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Thursday 4 December 1884, page 5

[xx] Register of Prisoners Brisbane Gaol 1879-1889 DR 91652. (QSA)

[xxi] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Friday 21 February 1890, page 5.

[xxii] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 15 December 1884, page 4

[xxiii] Register of Prisoners Brisbane Gaol 1879-1889 DR 91652. (QSA)

[xxiv] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Thursday 20 February 1890, page 5

[xxv] Queensland Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages, 1891/C/11921 and 1894/C/10860

[xxvi] Morning Post (Cairns, Qld. : 1897 – 1907), Wednesday 30 November 1898, page 3

[xxvii] Ireland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1620-1911

[xxviii] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 15 December 1884, page 4

[xxix] Register of Prisoners Brisbane Gaol 1879-1889 DR 91652. (QSA)

[xxx] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Friday 21 February 1890, page 5.

[xxxi] Queensland Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages, 1892

[xxxii] New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime (Sydney : 1860 – 1930), Wednesday 17 April 1901

[xxxiii] The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 – 1912) Wed 18 Sep 1907, Page 777, Family Notices

[xxxiv] Australia, Marriage Index, 1788-1950

[xxxv] Australia, Birth Index, 1788-1922

[xxxvi] Australia, Death Index, 1787-1985

[xxxvii] Australia, Death Index, 1787-1985

[xxxviii] 1861 Scotland Census

[xxxix] UK and Ireland, Masters and Mates Certificates, 1850-1922. 1881.

[xl] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 22 September 1884, page 5.

[xli] Register of Prisoners Brisbane Gaol 1879-1889 DR 91652 (QSA)

[xlii] Letter from Captain Pennefather, St Helena, The Hopeful Papers Part 1 – DR 112166 (QSA)

[xliii] Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Friday 21 February 1890, page 5.

[xliv] UK and Ireland, Masters and Mates Certificates, 1850-1922. 1892.

[xlv] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 22 September 1884, page 5.

[xlvi] DR 112167 (QSA) (Letter and report by A.J. Thynne, Minister for Justice, Crown Law Office 4 May 1889.)

[xlvii] Notes of conversation in Crown Solicitor’s office, 1884 DR 112168 (QSA)

[xlviii] Crew lists of the Hopeful DR 112168 (QSA)

[xlix] Queensland Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Registration 1883/C/1714.

[l] Notes of conversation in Crown Solicitor’s office, 1884) DR 112168 (QSA)

[li] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 21 May 1894, page 5. Petition for Divorce.

[lii] Queensland Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages. Registration 1894/C/1625

[liii] Notes of conversation in Crown Solicitor’s office, 1884 DR 112168 (QSA)

[liv] The Hopeful Papers Part 1 – DR 112166 (QSA)

[lv] Albury Banner and Wodonga Express (NSW : 1860 – 1938), Friday 22 March 1889, page 19

[lvi] Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld. : 1867 – 1919), Monday 18 May 1914, page 7

[lvii] Crew lists of the Hopeful DR 112168 (QSA)

[lviii] Manchester, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1915

[lix] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Thursday 4 December 1884, page 5

[lx] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 15 December 1884, page 4.

[lxi] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 15 December 1884, page 4

[lxii] Register of Prisoners Brisbane Gaol 1879-1889 DR 91652. (QSA)

[lxiii] Inquest into the death of Henry Schofield, ITM 2727856 (QSA)

[lxiv] Queensland Figaro and Punch (Brisbane, Qld. : 1885 – 1889), Saturday 30 January 1886, page 2.

[lxv] Australia, Find a Grave Index, 1800-current.

[lxvi] Regina v Bernard Williams Oral Evidence. Notes of Police Magistrate Pinnock (QSA)

[lxvii] The Hopeful Papers Part 1 – DR112166. Notes of Chief Justice Lilley (QSA)

[lxviii] Crew lists of the Hopeful, 1884 (QSA)

[lxix] New South Wales, Australia, Gaol Description and Entrance Books, 1818-1930

[lxx] The State Records Authority of New South Wales; Kingswood, NSW; Sheriff: copies of letters sent to Col Sec. and public officers 31 Jul 1866–31 Dec 1867, 3 Jan 1868–31 Mar 1870; Box: 3; Roll: 844

[lxxi] Queensland Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages. Registration details: 1876/C/796

[lxxii] Northern Miner (Charters Towers, Qld. : 1874 – 1954), Tuesday 24 October 1882, page 2

[lxxiii] Regina v Bernard Williams Oral Evidence. Notes of Police Magistrate Pinnock (QSA)

[lxxiv] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Thursday 4 December 1884, page 5

[lxxv] The Hopeful Papers Part 2 DR 112167 (QSA)

[lxxvi] Sands Directories: Sydney and New South Wales, Australia, 1858-1933

[lxxvii] Regina v Bernard Williams & Ors Oral Evidence. ITM 7868 (QSA)

[lxxviii] Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 – 1947), Monday 8 December 1884, page 4

[lxxix] The Brisbane Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Saturday 7 January 1885, page 4.