(A companion piece to “And who might you be, Sir?”)

In April 1876, Samuel Norman (alias Abrahams, Hope, Martin and Hunter) was put on trial for larceny as a bailee at St. George. He had borrowed a horse from a Mr Payne, neglected to return it or pay for it, and then exchanged the horse for another one.

Norman was not represented, and his fate hinged on his address to the jury. His skill as a public speaker was evident, as was his extraordinary imagination. Here, in his own words, is his tale:

“May it please your Honour and gentlemen of the jury, Most if not all of you are aware that I was residing here, practising my profession as a surgeon; you have heard the evidence against me, and now, in my turn, I ask you to accord me a patient hearing.

“In proceeding to defend myself from the charge brought against me, I will endeavour to impress on you the necessity of taking into consideration not only the facts of the case themselves, but the reasons, motives, and circumstances that led to those facts taking place.

“I am not, gentlemen, a believer in predestination, but I consider, and it is admitted by most thinking men, that our actions are at times controlled by circumstances, and that our lives run in a kind of groove between predestination and free agency, and that the force of circumstances impels us to take a certain course, and when the first law of nature – self-preservation – renders all others subservient for the time being.

“Law is, I believe, defined as being the perfection of human reason, and as such, it seeks the causes for effects and the motives for action as well as considering the effects and actions themselves. There is such a thing, I need not inform you, as justifiable homicide, when the law allows a man to take life in his own defence; if a starving man steals bread he is blameless; what man would be punished if, to save himself from great and imminent danger, he took the horse of another to extricate himself from that danger? and how much less culpable the exchange of a borrowed horse under circumstances when the life, perhaps, of his rider depended on the animal’s ability to carry him!

“This case, gentlemen of the jury, depends mainly on the evidence of two witnesses – Mr. Payne, the owner of the horse, and Mr. Luckman who afterwards gave me a horse in exchange for him. I admit that all the evidence given by Mr. Luckman, and the groundwork of that given by Mr. Payne to be substantially correct. It appears that before the present proceedings were instituted, Mr. Payne had taken out a warrant against me for obtaining the horse under false pretences, and his evidence would seem more calculated to establish that charge than the present one.

“I admit to hiring the horse from him, but not to go to Mr. O’Shanassy’s, or even to Surat, but to Roma. The story of my representing myself to be a Government official is entirely without foundation. There were two or three persons present, who knew me in St. George, and Payne admits that the mailman who accompanied me to within four miles of the place, preceding me by but one hour, announced to him that I was coming that way with a sick horse.

“Now, Payne states in his evidence, that when I rode up to the door, I told him my horse was sick; he already knew from the mailman that Doctor Norman was coming there, with a sick horse; and, knowing this what happens? One hour afterwards, a man rides up to the door, and tells him that his horse is sick; and yet he cannot guess that the man was Dr Norman. I then, he states, after sending the message that I was coming by the mailman, represented myself to be in the Government employment, and under that impression, he lent me the horse.

“Now it is altogether incredible that a sharp man like Mr Payne should be deceived by such a “cock and bull” story; and moreover, that he could be, by any means, induced to believe that I was being paid ten shillings per mile, as if Government officials were so liberally remunerated for their services. He, however, admits subsequently that he was aware of who I was, before I went away, and was, consequently disabused of his hallucination before he lent me the horse. A man who could turn the phrase, “there is nothing sure but death” – the expression I made use of when he asked me if I was sure to get a fresh horse at Mr. O’Shanassy’s – into the ridiculous but appalling expression, “There is nothing surer than sudden death,” can well be imagine to construe the fact that of my stating that I was going to Roma to attend a meeting of the Hospital committee, to apply for the appointment of hospital surgeon, into my assertion that I was on Government business; and my stating casually in the course of common conversation, in answer to the question, that I charged ten shillings per mile when sent for to see a patient, into the statement that I was receiving ten shillings per mile for my services in connection with the imaginary Government business aforesaid.

“Gentlemen of the jury, when I was practising in Brewarrina in New South Wales, I had, on two occasions, to attend a coroner’s inquest at some distance in the capacity of medical witness, when, in addition to my guinea fee, I was paid – not ten shillings a mile – but ninepence! From that I conclude that Government employees are not entitled to such munificent mileage. If Payne should either wilfully misrepresent, or ignorantly garble one portion of his evidence, does it not warrant you in rejecting the whole as unworthy testimony; or, at least, with looking upon it with mistrust and suspicion. Fancy a man interpreting the expression, “Well, I must get a horse somewhere,” into a demand for a horse. Any word, or words, singled out of a conversation, and undue emphasis put upon them, bear a different construction to that intended they should at the time spoken. Let me tell you, gentlemen of the jury, the “plain unvarnished tale” of the affair, and you shall judge which is the more worthy of credence, my simple statement or Payne’s improbable one, which, to say the least, he has I am afraid, coloured, with a view to strengthening his case.

“I left St. George with the Surat mailman, on the 10th January last. We came to, and remained at, Mr. John Moore’s station that night. On the road, the horse I was riding became so ill that it was a hard job to get him along from Moore’s the next morning. The mailman started for Payne’s before me, a distance of four miles, an hour before I did. I asked him to inform Mr Payne that I was coming, and that my horse was sick, in the hope that I might be able to obtain a fresh one from him. I managed to reach Payne’s and entering the house, gave him my card, and informed him who I was.

“I said, “My name is Norman – Dr. Norman;” he replied “Yes, I now, the mailman told me you were coming.” I explained how I was situated and asked him to lend or hire me a horse. He said he could not do so at first; but on my telling him what terms I was willing to give, and that my business was very urgent, as I wished to be in time for the Hospital meeting, he afterwards agreed, reluctantly, to try and get me one. Seeing him so reluctant, I told him I might not want his horse, as I expected to get one at Mr. O’Shanassy’s. He asked me if I was sure to get one there, and I replied that, “There is nothing sure but death;” and if I got another horse, I would not require his, and would leave it at O’Shannassy’s, but if not, I will take him on.

“There was nothing stipulated where I was to leave the horse or whether I was to bring him back. I agreed to pay him ten shillings per day for the hire of the hose, and explained to him that I sometimes had unexpected professional calls, and said I would give him one pound a day for any trip I might have to make beyond Roma. He then sent a blackfellow out after the horse. He was away about three hours. After the horse was brought up, I had dinner, and started soon after. I wish to impress upon you, gentlemen, that he was perfectly aware, all the time, that I was Dr. Norman. The mailman and several men were there acquainted with me, myself – my card – told him that; so that it is undoubtedly true, when he lent me the horse, he was cognizant of who I was; and I assert that I obtained the horse bona fide and not by means of any fraud or misrepresentation.

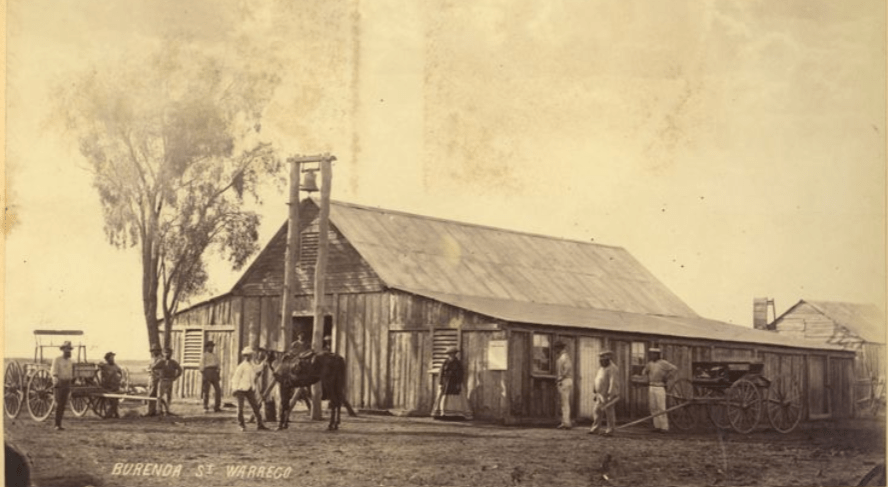

“I will trespass on your time but a little longer, gentlemen, while I pursue this narrative to its disastrous close. I could not obtain a fresh horse at Mr. O’Shanassy’s; but, in due time reached Roma with Payne’s horse, where, after transacting the business that brought me, I was further detained by the illness of the two resident medical men, and their practice devolving on me; and an epidemic – the measles -being very prevalent there. Seeing this, I sent Payne the telegram now before the court, telling him that I should require the horse for a week longer. In the meantime, a message came for medical assistance, from Burenda, in the Warrego district, where an alarming disease was raging, that had already carried off several station hands. Neither Dr Smith nor Dr De Leon was in a condition to go, so it devolved on me.

“I accordingly started for Burenda, and reached a road-side inn, called Black’s Water Hole, where I met with a mishap, that was indirectly the cause of this prosecution. I lost my horse for a week, and I afterwards discovered that he had been taken away and worked, and then turned out near the house. The horse, when recovered, showed signs of having been severely ridden; and on resuming my journey I found that he was tired, before I got far, he knocked up altogether. I had to drive him along in front of me, on foot, and had the greatest difficulty to keep him moving.

“I managed to reach the Angelala Downs station, 30 miles from Burenda, where I endeavoured to borrow a horse, but there had been a long drought, and horses fit for riding were scarce in consequence. I offered a young man working for Mr. Luckman £2 for the loan of his horse to go to Burenda, but he refused it. I could not borrow or hire, and I had not the means to purchase even if I could have found one to buy. I remained there next day in hopes that my horse might rest sufficiently to enable him to carry me to Burenda, but he was too completely done up to recover for weeks.

“I was in a critical position; I could not trespass on the hospitality of the station; I was anxious to get to Burenda, where so many were ill; but Burenda was thirty miles distant, with a desert of waterless scrub intervening. I thought of walking, but I was convinced that it would be suicidal to attempt such a thing; it would have been impossible for me to have travelled there, exposed to the blazing tropical sun, much more to have transported thither the drugs necessary to alleviate the sufferings of the fever-stricken inhabitants.

“I recollected with alarm that, not many days before, three experienced bushmen had lost themselves, and perished for want of water in that very district. “How,” I thought, “could I, not long in the colony, unaccustomed to being in the bush, hope to escape their miserable fate.” I felt that there was but one way to escape; but one way to prevent my bones being found one day by some stockman, bleaching beneath the rays of the pitiless sun – another added to the long list of men who had perished in that dreadful country, and, as the last chance for self-preservation, I adopted it.

“I resolved to exchange the horse I had hired from Payne for another; go on to Burenda, return to the Angelala, redeem Payne’s horse with the money I should be paid for my professional services, procure another at Burenda, and take him back to his owner, and satisfy his demands for the use of him.

“But, alas! how true is the proverb-“Man proposes, but God disposes;” that very day, not long after I had effected the exchange, I was arrested by the police on another charge – one of which I was entirely innocent, and for which I have been tried and acquitted in this courthouse – and I have ever since been in custody. If acquitted, the owner of neither horse will be at a loss, and I am willing and desirous to make restitution for what I was so involuntarily led to do. These, gentlemen, are the particulars of my hard case; and in conclusion, I ask you to suppose yourselves in my place, and mentally ask yourselves what you would have done, and judge accordingly. I ask if there is any evidence of wrongful or fraudulent conversion to my own use to justify you in finding me guilty of the charge. I thank you, gentlemen, for your patient hearing.”

Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser (Qld: 1866-1879) Saturday 29 April 1876, page 3, St. George.

Sadly for Dr Norman, the gentlemen of the jury found him guilty. The Judge was impressed by the articulate young man before the Court and gave him a discount on his term of imprisonment.