The woman on the riverbank.

On Friday 6 July 1883, a group of boys rowing up the Brisbane River noticed a person lying on the riverbank at North Quay. They pulled over to check, and discovered that it was a young woman, who had clearly been dead for several days. The lads went to fetch a constable immediately.

The young woman was short, brunette, of stoutish build, and she had remarkably small, thin hands. She had dressed with some care before she died – she was found wearing a “buff-coloured dress with golden-coloured spots, trimmed with golden-coloured satin and black lace, white gipsy hat trimmed with black lace and black feather, plain kid gloves, white-brown striped stockings; a plain-gold wedding-ring, a small gold hunting watch, a lady’s black-beaded albert chain, a black brooch and earrings, and a tortoiseshell comb in her hair.” On examination by Dr Marks, she was found to be five months pregnant, and in good health, apart from a fracture at the left base of her skull.

There were some letters found on the young woman’s body that tentatively identified her as a daughter of a Mr Borgert of Gowrie. Further enquiries found her to be Cecilia Bleck, also known as Celia Black, the wife of August Bleck (also called August Black) of Toowoomba. Cecilia’s remains were identified by relatives and friends, and the story of how she came to meet her death in Brisbane unfolded.

Good German stock.

On 10 November 1858, Caecilia Margaretha Borchert (also spelled Borgert) and her twin sister Coralie, were born in Schenefeld, Stienburg, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, to Johann and Antjie Borgert. Cecilia’s twin, Coralie, passed away in 1864, and the family emigrated to Queensland aboard the La Rochelle in 1865. Also on that voyage was the Bleck family, including then 20-year-old August, the second oldest of the six Bleck children.

Twelve years later, August Bleck married Cecilia Borgert, having not apparently been able or willing to do so during her pregnancy with his first child, Wilhem Carl Bleck (born 5 November 1877).

The Blecks lived on the Darling Downs and suffered the highs and lows of a poor 19th century immigrant family. Little Wilhelm Carl died in July 1878, and Cecilia gave birth to Albert Johan in early 1879. She would have another baby, a little girl who lived almost exactly a year, Anna Katherina, in 1881. Only Albert survived to maturity, passing away in 1941.

The road to ruin.

August Bleck seems to have been absent from the family home from time to time, probably out working or looking for work. Cecilia seems to have tried to keep herself and her young children as best she could, but ran into trouble with the law when she asked her younger sister, Catherine, to get some goods at a store in the name of another local woman. Cecilia was heavily pregnant at the time, and the goods (tea, soap etc) were to the value of nine shillings.

The shopkeeper realised that she had been imposed upon, and Catherine Borgert was initially charged with imposition. She was only twelve, so suspicion fell on Cecilia, who fronted court in February 1881 with three-week-old Anna Katherina in her arms. (Her young sister-in-law Louisa Bleck was also charged.) The court reporter noted that Cecilia was a respectably dressed young woman, and when she was found guilty, the Bench could not bear to send her to Toowoomba Gaol to associate with the ruffian females there, so she spent seven days in the lock-up as punishment. Louisa Bleck was given one month in Toowoomba Gaol because there was nowhere else to send her.

The Darling Downs Gazette thought that the youngsters involved in the imposition were a good argument for the establishment of a reformatory school for girls, to keep them from going “further and further on the road to ruin.” (A Reformatory for girls was opened in Toowoomba not long afterwards.)

An ill-assorted brothel.

For whatever reason, August Bleck was not around in 1882 when his house became the subject of intense local scrutiny. Ladies who were not family members resided with Mrs Bleck. Gentlemen who were not family members visited there at all hours. Singing, dancing and drinking took place there.

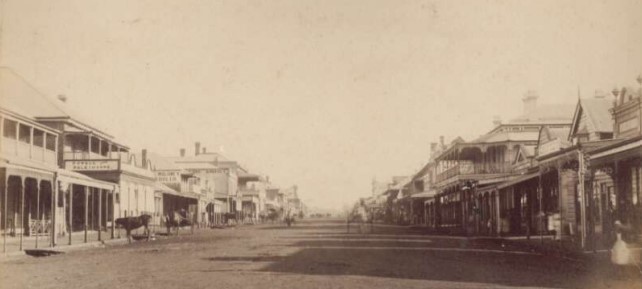

One night in early March 1882, neighbours heard a ruckus at the Bleck home on Ruthven Street, near the school. There was cursing and swearing, doors being banged on and “vile expressions made use of.” They summoned the police, who in turn summoned Cecilia Bleck for keeping “an ill-assorted brothel or disorderly house.” Mrs Bleck was committed to the July1882 sessions of the Circuit Court at Toowoomba.

A fire.

August Bleck’s house now stood empty. It erupted in flames in the early hours of 31 May 1882 and was completely destroyed. It had been insured, fortunately. An inquest was adjourned indefinitely on 14 July 1882, probably because Mrs Bleck was due to stand trial the following day. The Darling Downs Gazette speculated that the matter of the fire would probably lapse altogether.

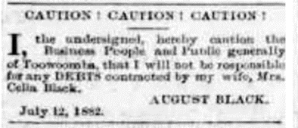

Faced with social and presumably economic ruin, August Bleck thoughtfully took out an advertisement:

The trial.

Celia Black, as she was known at Toowoomba, had pleaded not guilty, and had secured the services of Mr Frederick ffoulkes Swanwick, Esq, Barrister-at-Law, to defend her. She wasn’t going down without a fight, and Mr Swanwick busied himself subpoenaing witnesses. Male witnesses.

At the trial, the prosecution called Mary Troost, a servant at the house. She knew the names of the two young women living there with Mrs Bleck. She knew that gentlemen came and went, but she didn’t know what they did there.

Ethel Howard rather bravely told the court that she rented a room from Mrs Bleck in which to receive gentlemen, and to sleep in herself. Mrs Bleck, she said, knew what she was up to, and the life that she had lived beforehand. There had been drinking going on at the house. Yes, Ethel had seen Mrs Bleck drinking. Ethel fell out with Mrs Bleck, and they had a “punching match” on the verandah of the house.

Ethel’s partner, a bricklayer named Denis Kineavy, gave evidence of the drinking and dancing that went on at the Ruthven Street house. He denied that he ever threatened to burn the Bleck house down after Ethel’s fight with Cecilia. He denied that he was Ethel Howard’s fancy man. He lived on some savings, he said, not on Ethel’s earnings.

Another young woman residing at the Bleck house, Annie Brown, was not called as a witness. She too, from the evidence of the Misses Troost and Howard and Mr Kineavy, had danced with gentlemen.

The jury took very little time to find Cecilia Bleck guilty of the misdemeanor of running a bawdy house, and she was ordered to pay a fine of £10 or to be imprisoned in Toowoomba gaol for three months. She took the fine.

A wanton insult.

Cecilia Bleck had been convicted, her husband had washed his hands of her debts, and the house had burned down, but the Bleck case was not finished with Toowoomba. The Toowoomba Chronicle squeamishly reported on the witness subpoenas issued by Mr Swanwick for Cecilia’s defence. It appeared that a number of local gentlemen had received them. Gentlemen “whose reputation and social position ought to have preserved them from such a gratuitous insult.” There must have been frosty silences across the dinner tables of the town for some time.

None of the men who had received the gratuitous insult were called to give evidence, but, said the Chronicle, their good names had been besmirched. “The mere annoyance is not all. That could soon be outlived. The infamy is ten times worse than the vexation.” Mr Swanwick apologised to some of the men after the trial, claiming that he had issued the subpoenas in error. And then left town.

“You will see if my wife continues to live like she has done she will not live long.”

After the brothel trial, Cecilia Bleck seems to have lived off and on with her husband for a few months. In the last six months of her life, she moved to Brisbane and rented rooms from acquaintances, sometimes under an assumed name. She told friends that she was hiding from her husband. At times, August Bleck would come looking for her. Sometimes she would see him, other times not. Often, they met cordially. Sometimes they would fight, bitterly. At one point, August Bleck came to the place where his wife was staying and tried to take away her jewellery and clothing. He even demanded her false teeth, which made her cry out to her hosts for assistance. According to the lady concerned, Bleck had said that he would “finish her before that day twelve months.” (It is not known whether he took the poor woman’s teeth.)

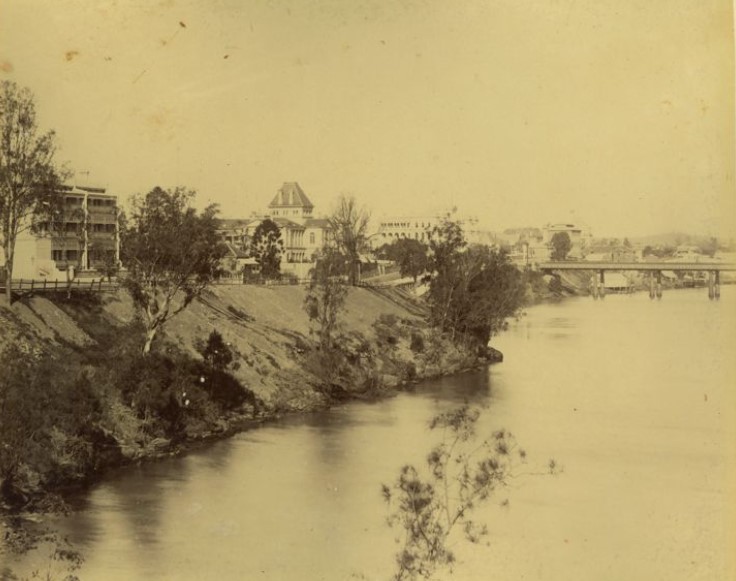

Mrs McLeod, with whom Cecilia Bleck had been living in Caxton Street at one point, recalled an afternoon walk by the riverbank, which ended with the couple fighting, and August Bleck telling his wife he would throw her over the riverbank and kill her.

The last place that Cecilia Bleck was known to have stayed was at the house of a tobacconist named Dowridge, on the corner of George and Turbot Streets. She stayed there under the name of Miss White. When August Bleck came knocking, looking for Mrs Black, Mr and Mrs Dowridge were able to say truthfully that there was no Cecilia Bleck or Black there. “Miss White” left the house on 27 June 1883. She had brought a box with her, but no-one knew where it or she went.

August Bleck had asked Denis Kineavy (the non-fancy man from the previous trial) to find his wife. He would give Kineavy £1 if he found her. According to Kineavy, he saw Bleck at Toowoomba on 7 July and asked for his reward – Mrs Bleck had been found, after all. Just dead on the riverbank.

August Bleck maintained that he had last seen his wife on 25 June, when she passed by him in Stanley Street, South Brisbane. He stopped her, and she asked him to take her back to live with him. He refused her for the present time, because of the bad life she had been living. He noticed that she was in the family way. He didn’t know who the father was. It might have been him.

He returned to Toowoomba on Monday 2 July, and several days later heard of his wife’s death from the police. He went to the morgue on 8 July, positively identified his wife and gave evidence at the inquest the following day. His mother and sister, residing in Stanley Street, gave evidence that corroborated August’s statements.

At the inquest, Dr Marks estimated that Cecilia had been dead for “about four days,” an estimate he expanded to “from five to seven days” at a later hearing. He gave the cause of death as exposure while insensible following a head injury caused either by slipping and hitting the head on a rock, or from a blow inflicted by another. The inquest ended with “suspicious circumstances – husband committed.”

Where had she been?

If Cecilia Bleck had been dead for five to seven days when she was found, she would have passed away between 28 June and 1 July. Even with repeated appeals, and rewards offered, no-one could trace Cecilia’s movements between leaving the Dowridge house on 27 June around 7 pm to the date when she was found at North Quay.

August Bleck did not help his cause with the conflicting remarks he made about his feelings towards Cecilia after she died. On 7 July at Toowoomba, Denis Kineavy took Bleck to see the Police about going to Brisbane for an identification. Kineavy made a weak joke in an awkward moment: “You were looking for a divorce, and you have got an everlasting one.” Bleck replied, “I don’t want any more women; it is a happy release; she was as rotten as a pear.”

The next day, after viewing her body at the morgue, he told Constable Fitzpatrick, “I did not speak to her since 25th June; I am not so sorry for her, but I am sorry for the way she ended.” On 12 July, Detective Nethercote arrested him for murder, Bleck said, “Thank God I am not in this; you will find out different. If I wanted to murder her, I could have done it long ago. She was my loving, dear wife, and I wanted to keep her.”

August Bleck was committed for trial for murdering Cecilia. He had a window of opportunity in which to commit the murder – he claimed to have last seen her two days before she left the Dowridge house, and he was still in Brisbane until 2 July, when he left for Toowoomba. His presence in Brisbane, plus the public arguments, and the self-incriminating statements, made him the prime suspect. However, the evidence against him was circumstantial, and no true bill was offered by the Attorney-General in November 1883.

Who killed Cecilia?

The time of death allows suspicion to fall on August, and he had previously made remarks about his wife not living a year. She was pregnant with a baby that may well have been someone else’s, and she had been in hiding at various houses in Brisbane. When she went to meet her death, she was well-dressed and clean. Perhaps she was going to meet a new man. Perhaps she was going to return to her husband. Perhaps she had the misfortune to run into a complete stranger, who assaulted her fatally.

She may have slipped and fallen down the riverbank, hitting her head on rocks as she went down, but there were no other injuries on her body to suggest that she had taken a fall. I think she was severely assaulted on the evening of 27 June, and her head injury slowly killed her. She may have been at the river all along, but if so, she was not noticed by anyone passing by on the water for at least a week. Perhaps she lay in someone’s shed, house or yard until she had to be moved. I do suspect August Bleck, but there is no witness evidence that puts him at North Quay.

Cecilia Bleck lived for only 25 years and saw a lot of hardship. She lost her twin sister, Coralie, at the age of six. The year after that, her family took a long ocean journey to the other side of the world, a place with a strange climate and language. She spoke basic English with and with a strong German accent (she lived with German people all her life and had needed an interpreter at a court hearing). She had her first child at nineteen and was married six weeks later. Two of her three children died in infancy. Her husband, with whom she had a fiery relationship, was away a lot, working or looking for work as a labourer. In the meantime, his young wife had to look after her family, often with no money coming in. Small wonder she turned to a nine-shilling fraud, and then running a disorderly house. All she had was the house – her husband had been away all the time she let out rooms to prostitutes. She lost all her teeth and had to wear dentures, which her husband paid for and wanted back when they parted ways. She lived in rented rooms in Brisbane, trying to avoid her husband. (Her son lived with her mother-in-law at the time.) She died of a head injury and exposure at 25 years of age, whilst pregnant with her fourth child.

Cecilia’s murder remains unsolved. The Queensland Figaro railed against the police when no bill was offered by the Crown Prosecutor in November 1883. “Never has the bungling inefficiency of the Police department of Brisbane been exhibited in stronger colours than in these proceedings against August Bleck.” After nearly five months in custody, Bleck was a free man, but was neither innocent nor guilty of the crime of murder.

August Bleck did not remarry and lived variously in Brisbane and on the Darling Downs. His brother Carl ran a successful omnibus and carrier service for many years, and sometimes August worked with him. August Bleck died in 1930. His only son outlived him by eleven years.

Evidence given by August Bleck at the inquest into his wife’s death on 9 July 1883:

August Bleck on oath saith: I am a labourer living at Toowoomba at the present time.

I left Brisbane on Monday the 2nd of July by the 3.40 train for Toowoomba. Up to a few days before I left, I had been working with my brother Carl Bleck. My last job was on Kangaroo Point. I was living at the time with my mother in William Street South Brisbane.

From something I heard from Sergeant Downey, I came on Saturday night from Toowoomba and on yesterday the 8th of July I was taken by Constable Fitzpatrick to the morgue. I there saw the dead body of a woman. The body was the body of my wife Cecilia Bleck. I identified her both by the body and dress. I had last seen her alive on the 25th of June in Stanley Street South Brisbane. We had been separated since the 24th of last February. She left me. She left of her own accord. I did not send her away.

On the 25th of June she was passing by Stanley Street, and I stopped her. She asked me to take her back. She said, “I want you to take me back and let me live with you.” I said, “No, I will not take you back at present.” I believed that she was living a bad life at the time. Before she left me, she had been leading a bad life and had been fined for keeping a bad house in Toowoomba. I was away at the time. After speaking to me she took the bus going into Brisbane. I did not see her alive again.

I know a tobacconist’s shop in George Street kept by a coloured man. He is known by the name of the Black Diamond (marginal note: Mr Dowridge). I called at his shop on the 28th May last in consequence of something I had heard of my wife. He told me that she had been there for two days but had gone to Toowoomba. I have made several enquiries about my wife to find her for the purpose of giving her a letter which I had received. I gave her the letter on the 20th of June. She came to my mother’s for it.

I never heard her threaten to take away her life and I do not know how she came to her death. I had asked her to return to live with me sometime in June before I saw her in Stanley Street, and I promised to forgive all that had passed if she would give up her bad life. She in reply told me that she would let me know in a day or two.

Adolph Wagner was on the platform when I left for Toowoomba. He is now living near the rope Factory Kangaroo point. Mr Scheffer saw me upon my arrival at Toowoomba. He took me to his place at Toowoomba.

On the Sunday night before I left, I slept at my mother’s house in South Brisbane. My mother’s sister, Albertina, and my little boy slept in the house. I went to bed shortly after sunset about half past six o’clock. I was not out of the house after that. On Monday I went and got a load of wood for my mother and had not much time to spare after. I told several people that I was going to Toowoomba on the Monday. I told my mother and sister that I was going. I went up to Toowoomba to work with a man named Griffiths who had written to me. I produce a letter and telegram which was the cause of my going to Toowoomba.

I have been married seven years. I have had three children by my wife, one only is living. I knew when I met my wife in Stanley Street that she was in the family way. I don’t know who the father of the child might be. I might be the father of it. August Bleck. Taken and sworn before me this ninth day of July AD 1883.

Hi Karen,

My great great grandfather Johann Borgert was Caecilie’s younger brother. I’m currently writing her biography. I looked in to evidence of her twin but she is not listed on Caecilie’s documentation I gathered from Germany. Thanks for telling her story. With the help of South Brisbane Cemetery her final resting place is now also known. Cheers-Jilly

LikeLike

Hi Karen, Caecilie was my great great grandfather’s sister. I’m writing her biography at the moment would love to cross check some of this information with you particularly regarding Coralie. Cheers, Jilly

LikeLike