How to “unlawfully, maliciously, and contemptuously, by overt act and deed, molest, disturb, vex, and trouble the preacher and congregation assembled for, and celebrating Divine worship.”

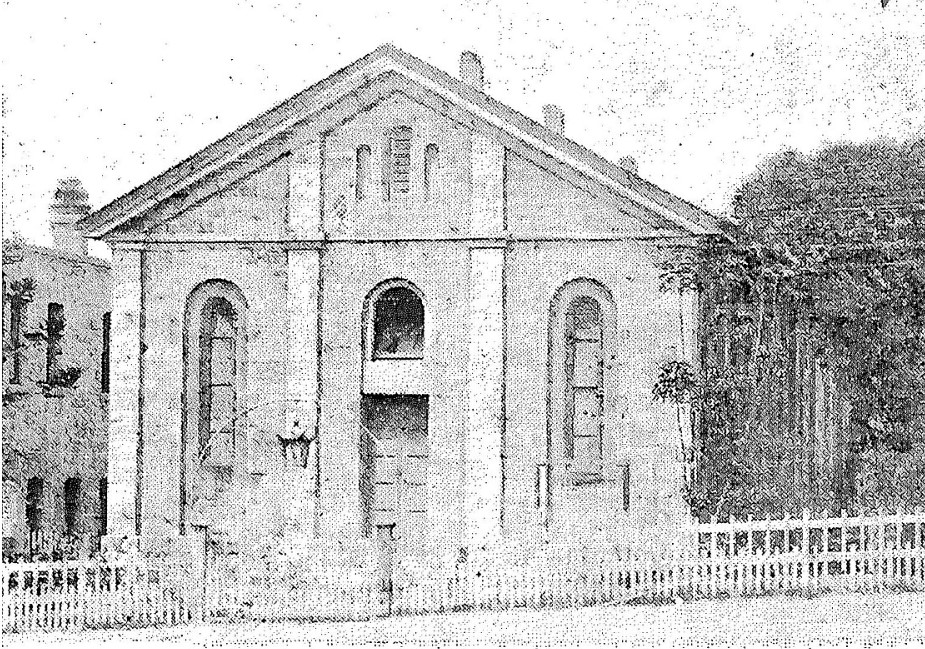

How did one William Langley come to be charged with the offence of disturbing a religious body under an Act that dated back to George III? He sat in the congregation of the Wharf Street Baptist Church on 2 November 1873, and opened and read his copy of the Church News.

A distressed fellow congregant, William Rooney, swore that he “could not worship God while there was a person holding a newspaper before my eyes with ‘Clarke and Treleaven’ and other advertisements.” I’m fairly sure God would have forgiven Mr Langley, but the church did not. He was charged as a criminal, and at his Police Court hearing, Langley was ordered to go to trial at the District Court, and to provide two sureties in the sum of £50 each.

William Langley’s malicious and contemptuous newspaper-reading had its origins in a long-standing, but hitherto fairly private, dispute with the board of the Wharf Street Baptist Church. Taking Langley to Court ensured that everyone in the Colony would know about the dispute for years to come.

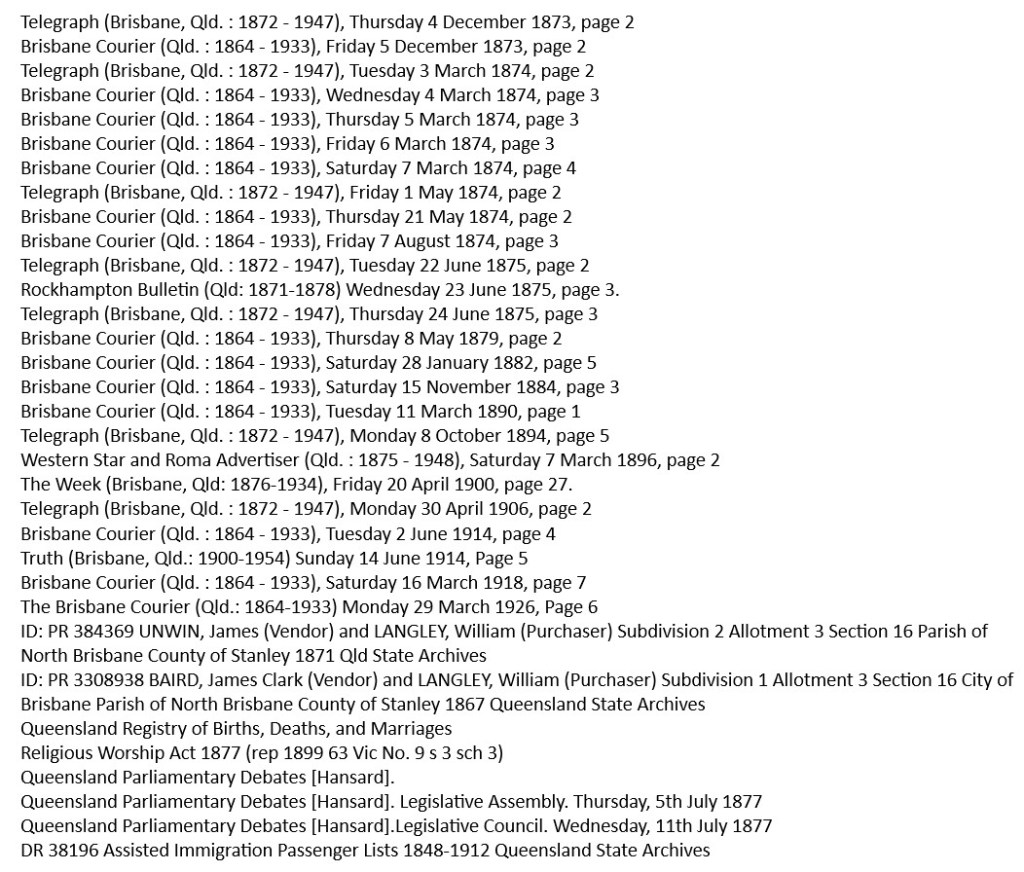

William Langley was a boot-maker with a shop in George Street, near the old Reservoir. He had been born in Toronto Canada around 1830, and migrated to Queensland with his wife and two daughters via the Royal Dane in April 1867. Initially he worked from a shop in Mary Street, then purchased “a poor, beggarly spot with the old reservoir in front, only half a roadway and no sidewalk” in George Street. Through his hard labour, he made the shop work, and his success encouraged other businesses to set up in that hitherto unloved part of town.

Unfortunately, Langley and one of his daughters became ill in the early 1870s and were assisted by the Wharf Street Baptist Church until they were back on their feet. After that time, he seems to have become – for want of a better term – a thorn in the side of the Church hierarchy, and he was advised that he was excluded from the Church in July 1871. The expulsion was probably due to a growing conflict with the pastor, Rev. Benjamin Gilmore Wilson. Langley could, and of course did, still attend those church services that were open for general attendance but could not attend the monthly meetings of members.

Thus, from 1872 through to 1875, Langley and Wilson were at odds, and the courts of Brisbane Town were kept busy with their writs and summonses.

Detaining a Letter and a Libel Action – 1872.

In February and March 1872, a letter circulated among certain members of the Wharf Street Baptist church. William Langley wrote a letter to the board of the church, sending it first to William Rowney for his opinion. His ten-year-old daughter Florence had taken it to be posted.

Mr Rowney had an opinion all right, and he sent the missive on to a Mr James B. Hall to read, who showed it to several other congregants. Rev. Wilson, who had got wind of the contents of the letter, demanded it at a Church meeting, and kept it. Hall had asked for it back, in order to return it to Langley, but Rev. Wilson refused to hand it over. Langley wrote to Wilson, asking for his letter back, but did not receive it. Langley then summoned Wison to the Magistrates Court for illegally detaining the letter. He lost the case because he had not made a proper legal demand for its restitution.

A week later, Rev. Wilson summoned William Langley for libel on the basis of the letter’s contents. After some tense negotiations in the court precincts, Langley withdrew the allegations in the letter, apologised to Wilson, promised to libel no more, and paid the costs. Rev. Wilson accepted graciously, and the case was withdrawn.

No doubt, William Langley’s regular attendance for Sunday worship at Wharf Street caused some awkward moments for Rev. Wilson, not to mention his more conservative supporters in the congregation. But the rest of 1872 passed without public incident.

A Libelous Pamphlet and Newspaper-Reading in Church – 1873.

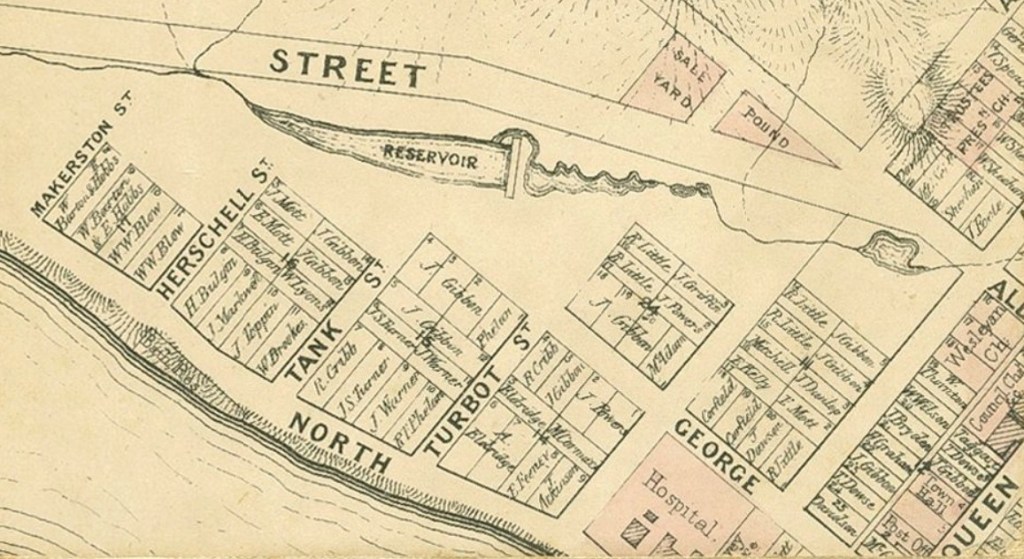

In April and May 1873, a couple of newspaper advertisements appeared for a curious sounding tract.

The Rev. Andrew Marvel? The only Rev. Andrew Marvel I have ever heard of was the father of the poet and politician Andrew Marvell (1621–1678). A bootmaker as Sole Agent for a tract concerning the use of libel proceedings against “members of independent churches?” Odd. Someone had been stewing over some slights in the religious community.

Nothing further happened until 2 November 1873, when William Langley brought his copy of the Church News to the Wharf Street Baptist Church. And read it. That was too much for the congregants at Wharf Street, and the Reverend Wilson decided that it was time to right past wrongs. Via the Courts.

The Maryborough Chronicle saw the amusing side of the situation:

“The congregation worshipping at the Wharf-street Baptist Church, Brisbane, have seen themselves compelled to call in the “secular arm” to restrain the vagaries of one of their own number, who had been guilty of the heinous impropriety of reading a ‘newspaper’ in church. The ‘newspaper’ was neither, Figaro, Fun, nor Bell’s Life, but that highly respectable and staid, though somewhat dull publication, yclept the Church News; the conductors of which, by the way, must be beside themselves with pride and delight to find their bantling figuring in the law reports of the daily journals as a ‘newspaper.'”

The Rockhampton Bulletin quite frankly did not:

“In the Wharf-street Baptist church there have been repeated disturbances caused by a man who in charity we must term a lunatic. This person is regular in his attendance and sits in a prominent place in front of the preacher. His tricks are of an extraordinary character. Sometimes he interrupts the proceedings by starting a prayer; at other times he interrupts the preacher by a loud voiced ‘Amen.’ He also reads newspapers and books prominently during worship. His latest freak is to sit through the service with his hat on and do his best to make everyone in the church uncomfortable.”

Imagine.

No sooner was William Langley committed to stand trial at the Brisbane District Court for disturbing a religious body than a criminal complaint was filed against Langley for “publishing a libelous pamphlet against the Rev. Benjamin Gilmore Wilson.” That was “An Antidote to Deadly Nightshade,” which had been advertised in May that year.

Litigation and a Rumpus at the Church Gate – 1874.

The libel proceedings ran from late 1873 to early 1874. The charge read:

“That on the 27th of May 1873, the said William Langley, unlawfully, wickedly, and maliciously, did write and publish, and caused and procured to be written and published, a certain false, scandalous, malicious, and defamatory libel in the form of a pamphlet entitled ‘An Antidote to Deadly Nightshade, a Tract for the Times,’ by the Rev. Andrew Marvel, BM,’ in a certain part of which said pamphlet were and are contained certain false, scandalous, malicious, and defamatory matters and things of and concerning the Rev B G Wilson, and of and concerning his conduct and character as the minister of the said church and congregation.”

The Crown surprised Langley by bringing his 1872 letter into evidence. He argued that it was a privileged communication and pointed out the settlement made in the Magistrates Court the previous year. Ronald Moresby, Assistant Clerk of Petty Sessions was brought in and examined about the settlement in that case file, but as luck would have it, he couldn’t find it. The letter went into evidence.

The pamphlet did not name the Rev. B.G. Wilson, the Wharf Street Baptist Church, or any of its board or congregants. Only those personally acquainted with the Langley-Wilson dispute would have had any interest in the tract, or been able to identify “Coombes,” the clerical character described. And the pamphlet, it turned out, had only been published to its one purchaser, Mr Cooksley of the Wharf Street Baptist Church. Oh, and the printer, Charles Mills.

A libelous or defamatory publication under our law meant this: – A publication whether by word of mouth, in writing, or print, without lawful justification or excuse, calculated to bring any man into public hatred, contempt or ridicule. First, then, they had the question – Was this published, and if published, was it published only to the members of the Church? Then, was it meant to apply to the Rev. B. G Wilson, and did the different passages in the information bear substantially the meaning imputed to them by the Crown?

Part of Judge Charles Lilley’s summing-up.

These were the issues the jury had to decide on. They retired to consider them at 3 pm. The judge called them back at 7 pm to ask if they had a verdict. They did not. Judge Lilley said that he would check with them again at 10:45 pm.

At 10:45 pm, the jury still could not agree, and were reluctantly locked up overnight. The judge apologised for the few refreshments available to them – some buns and ginger beer or lemonade. One juror hopefully asked for a glass or beer instead, but “His Honour said he had no power to allow this indulgence.”

The following morning, 6 March 1874, the beerless jury were asked if they had agreed on a verdict, and His Honour received “several very emphatic replies in the negative.” They were discharged, and William Langley was allowed to enter into recognisances to appear for his trial if and when called upon.

William Langley continued to attend the Wharf Street Baptist Church throughout the various trials. In April 1874, the Wharf Street Baptist Church decided to try and exclude him from the public services and posted John Long at the door to prevent Langley’s entry. Mr Long did this with so much enthusiasm that Langley summoned him for assault.

A Roman Catholic or a Unitarian, a Swedenborgian or a prostitute could go in; we should be glad to see them if they behaved themselves.

Brisbane Mayor and Trustee of the Wharf Street Baptist Church, James Swan, on the church’s open-door policy for public worship.

I never interfered with the bread and wine; I never interfered with the administration of the sacrament; I was once ordered out like a dog; I never behaved unseemly at any time.

William Langley on his experience of the church’s open-door policy.

Witnesses described a scuffle at the entrance to the Church, with Mr Long hustling Mr Langley down to the gate, and knocking him off his feet. The defence argued their right to exclude unruly persons, and recited the sorry history of Langley’s disruptive presence in their midst. The Bench of Magistrates gave a majority ruling to convict John Long, and fine him 40 shillings.

That was a bit much for the Church, and Mr Long in particular, who applied to the Supreme Court writ of prohibition, seeking an order overturning the conviction.

The writ was not finally decided until August 1874. Long’s (and by extension, the Church’s) application was that the conviction of Long by the majority of the Bench of Magistrates was erroneous and contrary to law. A lot of legal argument was raised about whether the church had a right to prevent William Langley entering the church, and whether William Langley had a right to attend the church.

Chief Justice Sir James Cockle, Mr Justice Lilley and Mr Justice Sheppard listened politely to the various submissions. And then very politely reminded the parties that this was in fact an appeal of a decision in an assault case. There was plenty of evidence that Mr Long had used force on Mr Langley, and that force was the basis of the conviction.

In other words, William Langley won. As unwelcome as he may have been at Wharf Street, his forcible expulsion from its grounds was an unlawful assault. The warring parties retreated from the courtrooms of the Colony.

A Paper War – 1875.

In 1875, H.G. Simpson introduced a bill to the Legislative Council to “prevent and punish disorderly conduct” in places of worship. The Legislative Assembly voted it down that year, but a form of it became law in 1877. The discussion around the proposed Act in 1875 gave rise to various Letters to the Editor from the interested parties – William Langley, James Swan, and a few pseudonymous authors.

Mr. Editor, I can’t help my presence; if I am not as handsome as other people, or if there is something peculiar in my physical organisation, I am not to blame for it. I would not like to let my mind get into such a state that it would be pained by any man’s presence in a place where he had as much right as I. I have a right to go to church as well as anybody else, and particularly to the church that was built for me and those holding the same views. I may be obtuse in my perceptions, but I cannot see that I should be compelled to leave the church of which I am a member because someone connected with that church allows himself to be disturbed and pained by my presence. And one thing is certain, no “Religious Worship Act” can compel me to leave off attending such a church.

William Langley, The Telegraph, 1875.

So far from the church ‘being built for him,’ he never contributed one penny towards its erection or maintenance; and as treasurer of the church, I am not aware that one fraction of a current coin of the realm has ever been received from him towards the support of either church or minister. I can fully bear out all that has been said by the three correspondents referred to as to his repeatedly annoying the congregation, and much more might have been truthfully said upon the same subject.

James Swan, The Telegraph, 1875.

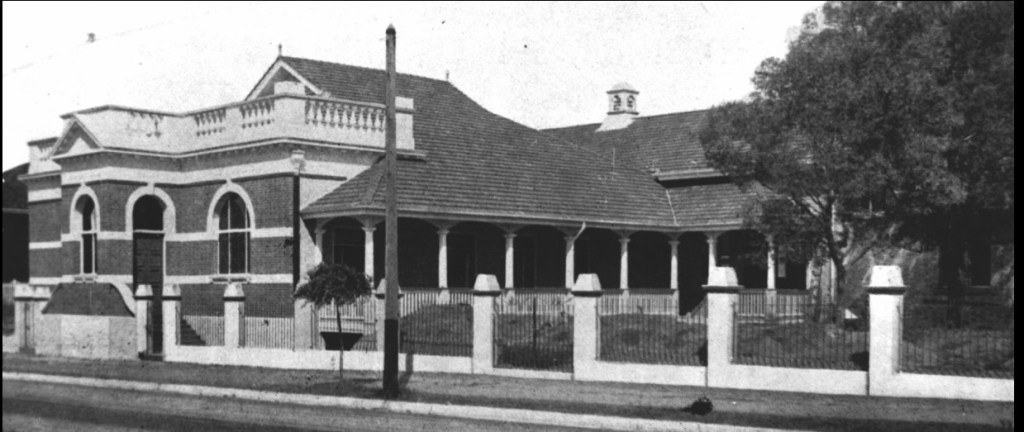

The Wharf Street War ended there. William Langley went about his life. He purchased a home in Herschell Street, where his eldest daughter, Mary, married Benjamin Oakden Brookes (Brisbane royalty) in 1879. In 1890, his younger daughter Florence passed away, and four years later his wife Hannah died. He would remarry, to Jessie Grover, in 1898.

Battling on.

William Langley still found time to argue with people, though. In 1884, he had a small fracas with one George de Courcey in George Street, resulting in cross-summonses. The court dismissed both claims, which arose from a rental dispute. In 1896, he decided that the decimal system would be a simpler method of governing the currency and campaigned and published – of course – a pamphlet in support of his belief. He was 70 years ahead of his time.

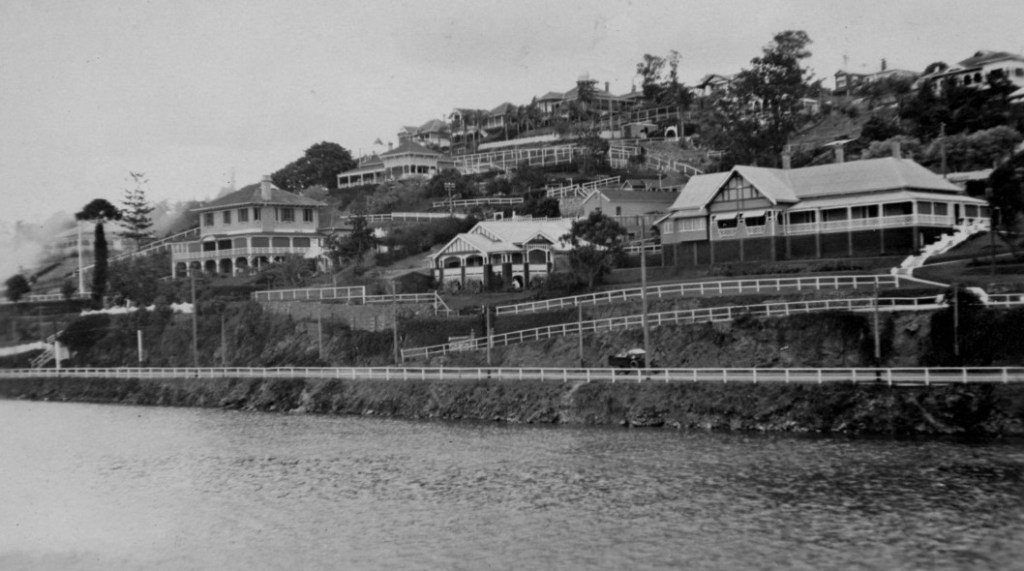

In 1900, William found a new nemesis- local government. He had done well in life, and had moved to the riverside suburb of Hamilton, planted some fine trees, and looked forward to spending his final years gazing at the river. Then he found out that there were plans to fill in part of the river and build a wall. This, Langley felt, would ruin “a piece of water compared with which the Barron Falls are insignificant.” The Council regretted that it had no jurisdiction over the matter, and William Langley decided that the council would keep.

1906 saw a property dispute with his estranged son-in-law, Benjamin Brookes, reach the Supreme Court. Brookes had come down in the world somewhat in the last 20 years. His marriage was in strife, he was no longer a man of means, and he fell out with his redoubtable father-in-law. Brookes decided to go north to try his hand at sugar planting and returned to find his wife living with her father at Herschell Street. When William Langley remarried, he moved to Hamilton, and Mary stayed on at Herschell Street and set up a boarding house. The trouble was, she had kept a lot of Benjamin Brookes’ furniture, and her father had sold it in lieu of rent. Mr Justice Real persuaded the men to reach a settlement, rather than continue to fight in court in a manner that could be distressing to Benjamin and Mary’s children.

William Langley had unfinished business with the council, or rather it had unfinished business with him. In 1914, at the age of 84, Langley appeared in the summons court with his gardener, charged with cutting trees on land controlled by the council. Langley arrived at court with a camphor-laurel branch, which he put into evidence, and spoke of planting the trees himself in 1900, having made his part of Hamilton “an oasis in the wilderness,” and the “prettiest in the district.” He had always maintained the trees, and the council was aware of this fact. His gardener had used a particular method of “polling” the trees to ensure that their continued health. Then, he got to what he considered the crux of the matter:

To the police magistrate: It is all a bit of spite, your worship, because I published a pamphlet about the illegality throughout. (Witness produced the pamphlet.)

Mr. Hobbs: Oh! We don’t want that; it has nothing to do with the case.

Witness: My place is an example to all. I have exposed them thoroughly in that pamphlet, and they can sue me for libel if they like. If anyone was asked if I was doing good to the district, they would say yes.

The Police Magistrate: I shall go out and see the trees.

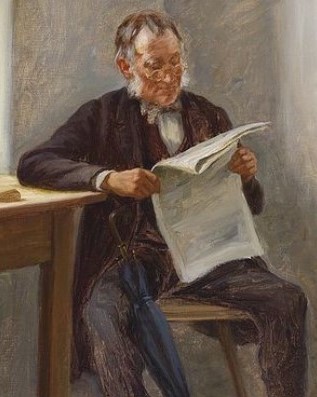

William Langley in 1914, as sketched by The Truth.

Still writing pamphlets after all those years! He lost this case and was ordered to pay three quid to the Council. I like to imagine that he paid it in pennies on the last possible date.

William Langley’s last enemy was the State Government. He paid Federal land taxes, and income tax – fair enough. It was 1918, and there was a war on. But when the State imposed a land tax on his property in George Street, and had no part in funding the war effort, he felt that he had to make public his views on the subject.

A VICIOUS AND INIQUITOUS ACT. TO THE EDITOR.

Sir.—Citizens who are heavily penalised by the Land Tax Act naturally shrink from making known to the public their private affairs, and the consequence is that the Government takes advantage of the silence, and asserts that no one is hurt. In the public interest I lay my private feelings aside and tell my experiences. I am not, nor have I been a land grabber or speculator. Fifty years ago, I purchased an allotment with the object of getting, as soon as possible, free of paying rent. The piece of ground went begging in Dickson and Dunkin’s hands at £120, and was of no value to me till I put value on it. It was a poor, beggarly spot with the old reservoir in front, only half a roadway and no sidewalk. I was the pioneer at that end of George Street, and helped to make the street, and now that my thrift, industry and enterprise are bringing me some returns this Government has taken as land tax £65. In May 1916, and another £65 six months afterwards, besides £10/19/ Income tax from the same property -£140/19/ in all for the year. The Federal taxes were: Land tax, £5/12/6, income tax, £9/10/6; for the year, £15/-2/. The State, without any war responsibilities, took from me £124/7/6 more than the Commonwealth, notwithstanding all the latter’s war requirements —I am sir, &c.,

W. LANGLEY. Hamilton, March 3.

William Langley died, one hopes peacefully, at his home at Hamilton in 1926. He was 96 years old. His daughter Mary lived on to the age of 88, dying in Sydney in 1943. Benjamin Brookes died of complications from diabetes in the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum in 1918.

Extract from 1872 Letter:

Sources: