How a terrible mistake cost a life and changed the law.

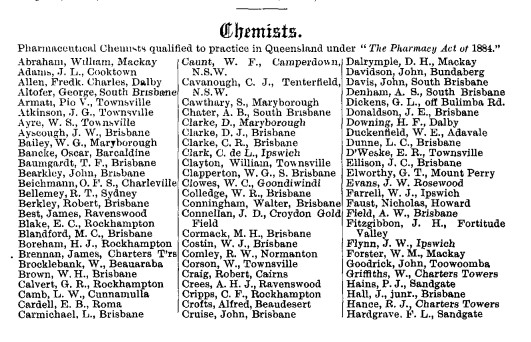

OFFICIAL NOTIFICATIONS. [From today’s Government Gazette.] MEDICAL BOARD. – Henry Duckers and Robert James Hance, of Brisbane; and James Wilkinson, of Townsville, have been admitted as chemists and druggists.

The Brisbane Courier, July 8, 1882.

Sophia Jacobi’s baby James Francis Jacobi turned seven months old on July 11, 1882. The following day, he would be dead, the victim of a fatal mistake made by a newly appointed chemist.

Sophia’s baby had been born out of wedlock, but she was about to marry his father, James McIntyre. The couple lived in Grey Street, South Brisbane. Little James had been a fine healthy boy, but around 12 July 1882, he became ill with whooping cough. Sophia consulted her neighbour, a midwife named Martha Tilney, who went with her to Haine’s Chemist on Stanley Street.

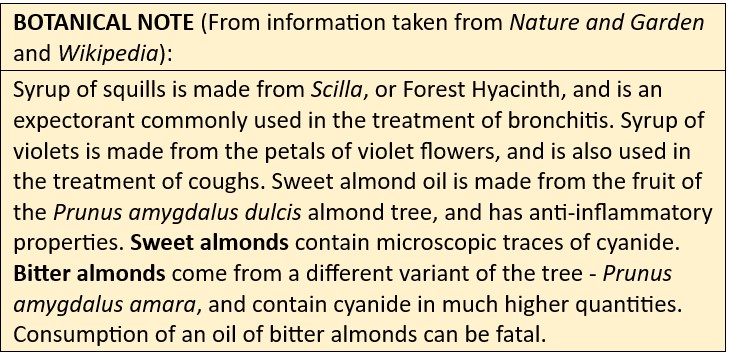

Martha was a woman who knew her remedies, and she asked the chemist’s assistant, Robert James Hance, for a mixture of syrup of squills, syrup of violets and oil of sweet almonds to treat whooping cough in a baby. Martha swore by the remedy, which had been used by her family for thirty years.

Robert Hance made up the mixture, advising Sophia to administer half a teaspoon twice daily.

When Sophia got home and gave her baby half a teaspoon of the mixture, she noticed that his tongue and lips immediately became white, and he had trouble breathing. Martha Tilney hurried to Sophia’s house and tried to induce the child to vomit. Having no luck, and with the baby fading quickly, Dr Tuck was called in. Dr Tuck noticed a smell of bitter almonds on the child’s breath, and urgently sent for Dr Clarkson, who had a stomach pump. Despite immediate medical attention, James died within fifteen minutes of being given the mixture.

Dr Tuck took the medicine bottle and went to Haine’s Chemist Shop and asked Robert Hance what he had dispensed for Sophia’s baby.

What he found out shocked him. The chemist’s assistant admitted that he hadn’t measured the ingredients and had no idea that there were two kinds of almond oil – sweet and bitter. He also did not know that bitter almond oil was poisonous. Even if he had known, not all bottles of bitter almond oil were labelled as poisonous at that time, which could confuse even experienced chemists.

A post-mortem conducted by Dr Purcell showed that the stomach contents of the child had a strong smell of bitter almonds, a conclusion supported by an analysis made by Dr Carl Staiger. The boy had about six grains of oil of bitter almonds in his stomach, and this had killed him.

Robert James Hance was charged with manslaughter. The issue the jury was faced with was whether his gross ignorance of the properties of the medicines he dispensed amounted to criminal culpability, or whether it was a bona fide mistake. He was found guilty, but the jury recommended him to mercy, “on account of the lax way in which chemists were allowed to practise in this colony.” Mr Justice Pring sentenced Hance to three months in Brisbane Gaol, but would not order hard labour because he didn’t want Hance mixing with the rougher inmates.

Robert James Hance was a 35-year-old Irishman who had come to Australia on the Potosi earlier that year. He was 5 feet 6, of proportionate build, with sandy brown hair and grey eyes. He may have worked in a chemist’s shop in Ireland previously or have undertaken some study, but the evidence at his hearings showed that he had little knowledge of his chosen field. He was admitted by the Medical Board of Queensland as a chemist and druggist barely a week before he made the fatal mixture.

Another chemist, Robert Berkley, had employed Hance for a few days but had dismissed him, believing him to be incompetent. Berkley would later admit that it would be hard for a new assistant to find the correct bottles on the shelves, although being unfamiliar with them should have made Hance more cautious.

The issue of how a person came to be appointed to handle dangerous medicines when he couldn’t distinguish between them had been raised in the press and had occupied the minds of Justice Pring and the jury.

There would seem to be no board of examiners, and it is a matter of history that very little learning is required to enable a person to obtain a chemist and druggist’s certificate from the medical board of Queensland.

Warwick Argus, 25 July 1882.

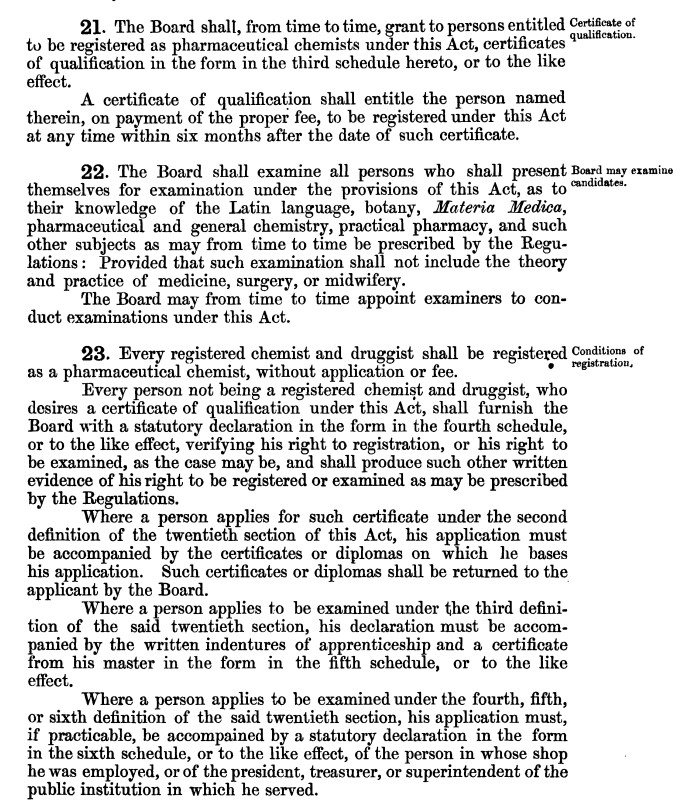

Two years after Hance’s conviction, an Act was passed in the Queensland Parliament to ensure that candidates for admission to work as a chemist and druggist would be properly scrutinised. The Board suddenly found itself with more responsibility and accountability.

Robert Hance served his short sentence, and after that, he – presumably – undertook the proper training and study and became certified as a chemist. He fetched up in Charters Towers, where he would live and work for the rest of his life. He joined the Grand Lodge of Freemasons of Ireland (Lodge 340, Charters Towers), and married Florence Sarah Wilkinson on 22 January 1891.

Robert and Florence Hance had four children – William John in 1891, Emily Martha in 1893, Thomas Shepherd in 1894 and Gladys Hilda Teline in 1895. William John passed away in 1892. Robert Hance died of pneumonia on 30 September 1899, and is buried in Charters Towers Cemetery.

Sophia Jacobi McIntyre Keith had two more sons with her husband James. James Senior passed away in 1899, and Sophia died in 1910, aged 50. The couple share a grave with their infant son, James Francis Jacobi McIntyre, in South Brisbane Cemetery.

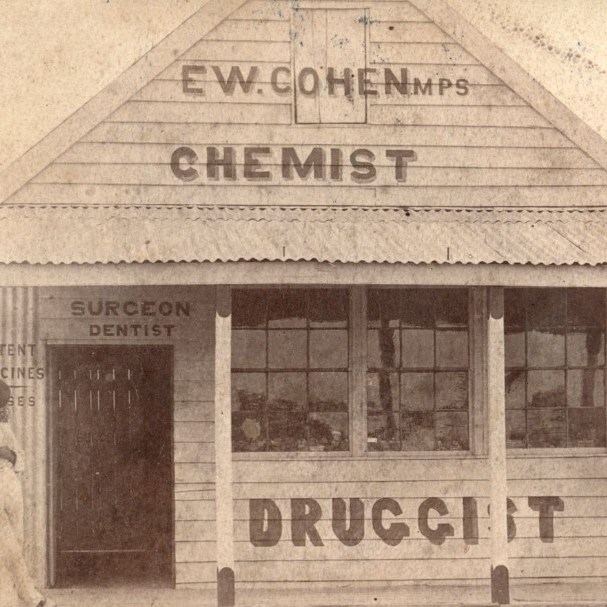

The life of a chemist in the 1880s – the Brisbane Medical Hall, Cohen’s Chemist in Longreach.

Advertisements for Chemists from Pugh’s Almanac