There were quite a few gentlemen who rejoiced in the sobriquet “Tom the Devil” in the 19th century. Tom the Devil seemed to be like the Flying Pieman or Dread Pirate Roberts – once someone was finished with the appellation, another individual would take over in the role.

The Original Devil.

The original Tom the Devil was Tom Honam, a militia man in the Irish 1798 uprising, who invented and/or perfected horrible tortures on prisoners. Honam was principally remembered for “pitchcapping,” which involved the use of boiling hot pitch on the scalp.

The American Devil.

In America Tom the Devil was Tom Cline, a man apparently given to demanding that his companions say their prayers at gunpoint. The last time this happened, in 1886, his victim was a farmer named Lee. Mr Lee was so miffed at this treatment that he shot Tom the Devil dead.

The Tasmanian Devil.

In 1868, a Tasmanian Tom the Devil troubled the administration of local government. One Fitzgerald, a Council Clerk in the municipality of Sorrell, was Catholic, and was thus suspected of Fenian tendencies. Thomas Keneene,”a frequenter of sundry public houses,” who called himself Tom the Devil, may or may not have claimed in public to have received ten shillings from, or given ten shillings to, Mr Fitzgerald for “Fenian purposes.” This tale caused the Council to undertake a public enquiry. Tom the Devil had to be produced to the Council to deny the Fenian transaction had taken place. Or had been boasted about. Mr Fitzsimmons was cleared of all Fenian suspicion as a result and got to keep his job.

The Devil in Victoria.

Victoria had its own Tom the Devil in the person of Thomas or James Gould, described by one paper as “an unmitigated nuisance.” Gould was a thief and drunkard who plagued the townships of Yackandandah and Beechworth with his rum-soaked presence. At one point during one of his sentences, Gould volunteered as hangman for the Beechworth Gaol. He received indulgences for doing it, and after all, he could drink any bad memories away.

Years later, Gould was in a cell at Yackandandah, sleeping off a binge, when a man named Francis Neville was put in with him. Neville had been a great friend of one of the men that Gould had executed. Mr Neville combined a long memory with the build of a heavyweight boxer, and proceeded to give Tom the Devil a beating he would never forget. The authorities at last wrested Neville off Tom the Devil and were shocked to see the big man go down on his knees, in tears, begging to be put back in the cell for ten more minutes. He wanted to finish castigating Gould properly.

Queensland’s Tom the Devil.

Queensland had its own Tom the Devil, a man who spent his youth stealing horses and his middle age paying for his crimes. Our Tom the Devil was Thomas Carey, who had arrived in Brisbane Town at the age of 13 as a labourer, aboard the immigrant ship Mangleton.

He was so young and friendless that the well-known auctioneer and horse-fancier Charles Mattorini took him in and gave him employment. After a couple of years of steady work, young Tom repaid this generosity by falling into bad company, drinking and staying out late at night. Carey’s services were eventually dispensed with. (By the time Tom started getting into trouble, prison authorities were noting that he had a brother and sister in Toowoomba, and a sister in Brisbane.)

In 1868, at the age of 20, Thomas Carey was a fully-fledged criminal, complete with an alias – Thomas Geary. When he worked, he was a horse trainer. When he wasn’t working, he was a horse thief. And not a terribly good one.

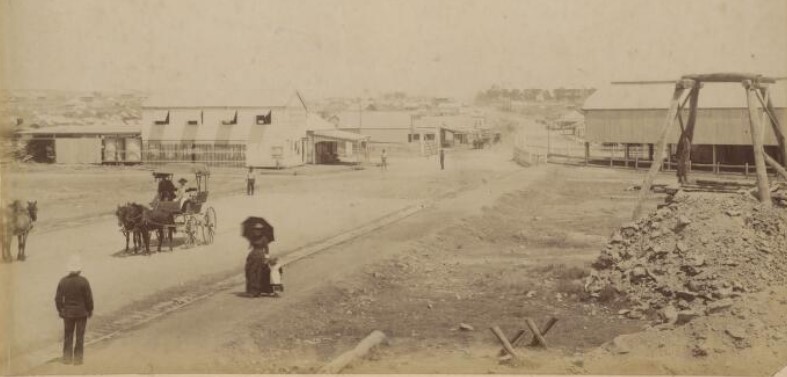

The prisoner hooked it – Taroom, 1868.

On the evening of 1 July 1868, Tom Carey was passing through Taroom, and happened to see a bay gelding he liked the look of. Shanks’s pony was rather tiresome, and he was on his way to Donnybrook outside of Roma. A nice ride would be just the ticket. Carey took the horse and began to ride away from the township at a leisurely pace that would attract no suspicion.

Unfortunately for Tom, the owner of the horse spotted him. Charles Ryder, a German (with a decidedly un-Germanic name) who kept the pound at Taroom, had only just let his bay gelding out of the paddock to forage in the bush, when he noticed it was being ridden away by a stranger.

Ryder took advantage of a shortcut, and managed to intercept the horse on foot. He grabbed the reins and asked the rider what he thought he was doing. The rider, a tall, well-built young man with a distinctive cocked nose, said that there must be a mistake. The horse was his. Ryder informed the stranger of the length of time he’d owned the horse, and for good measure, called out “Police!” At which point, as Charles Ryder later related in Court to Judge Lutwyche, “the prisoner hooked it.”

Once the court resolved the issue of the appropriate use of slang, the jury retired for a very short time, and found Thomas Carey guilty of horse-stealing. His sentence was two years’ hard labour in Brisbane Gaol. Which meant St Helena Island – a charming spot in Moreton Bay that was rather spoiled by a prison that had been plonked there a year before.

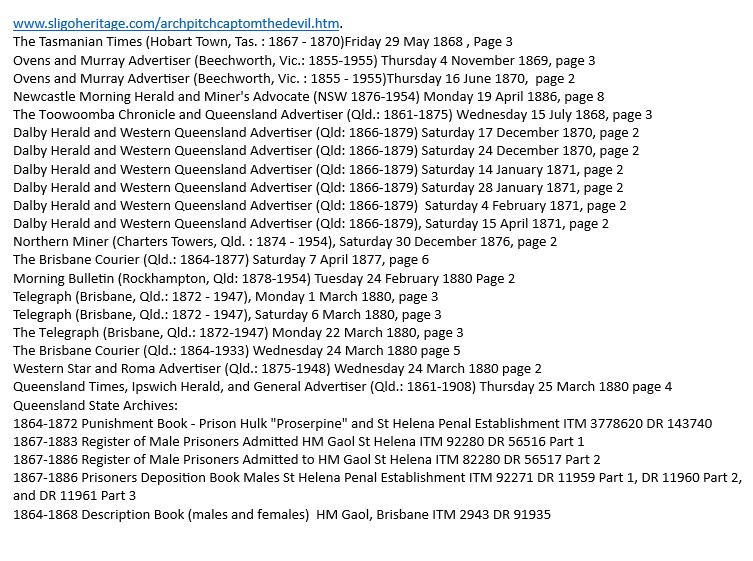

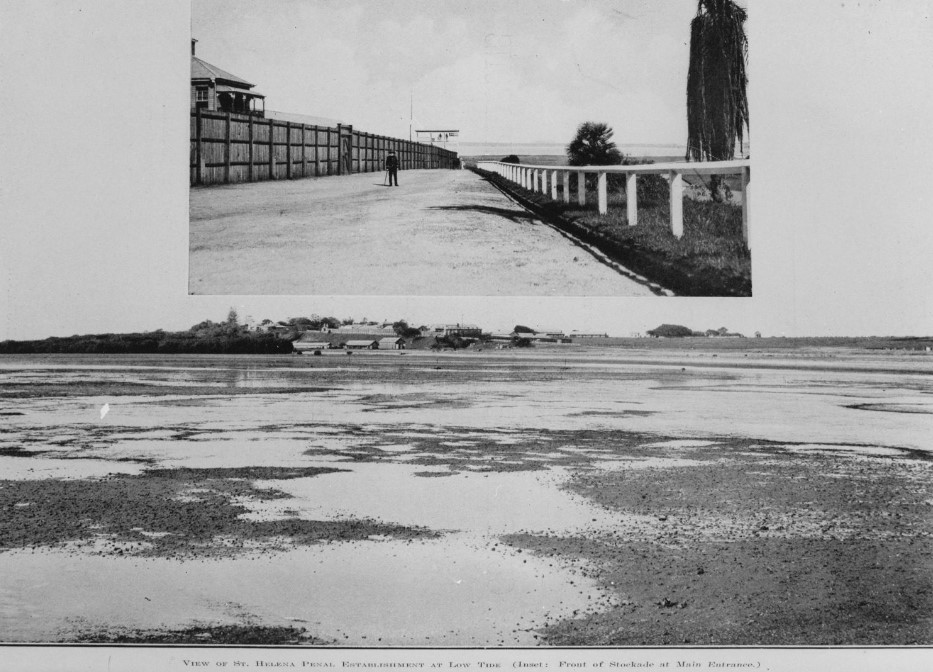

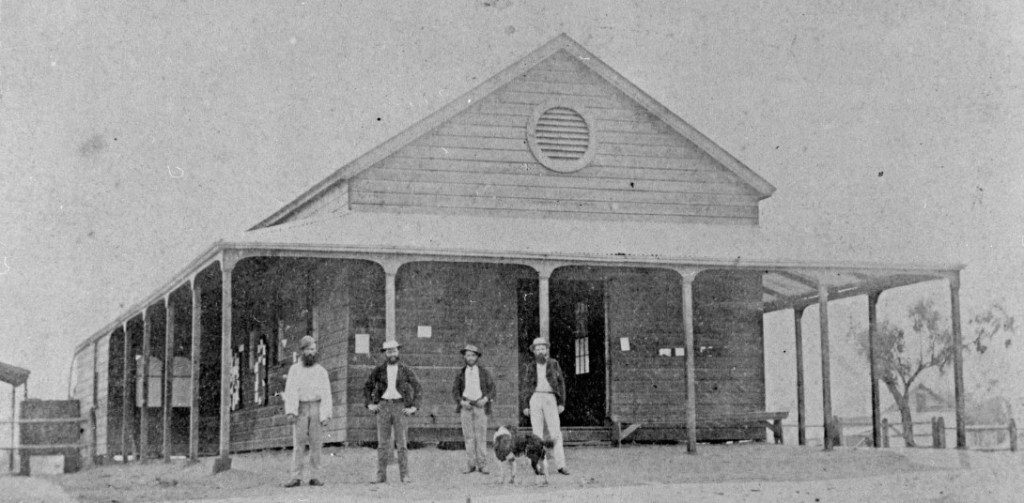

St Helena Island – home for various periods between 1868 and 1890.

Clockwise from top left: St Helena at low tide, with inset of the entrance to the Stockade. A field gang at St Helena. The rear of the Stockade. The Tailor’s Shop at St Helena Island.

Carey spent his two years there mingling with the likes of the Wild Scotchman (James McPherson), the Wild Frenchman (Henry Hunter alias Russell) and The Snob (Edward Hartigan alias Cahill alias Parker). The Snob, whose cell was quite near Carey’s, was probably the most dangerous of these fellow inmates. While Carey was there, Hartigan became involved in a vicious dispute with another prisoner, stabbed two others, and spent a lot of time cooling off in a “dark” cell on bread and water.

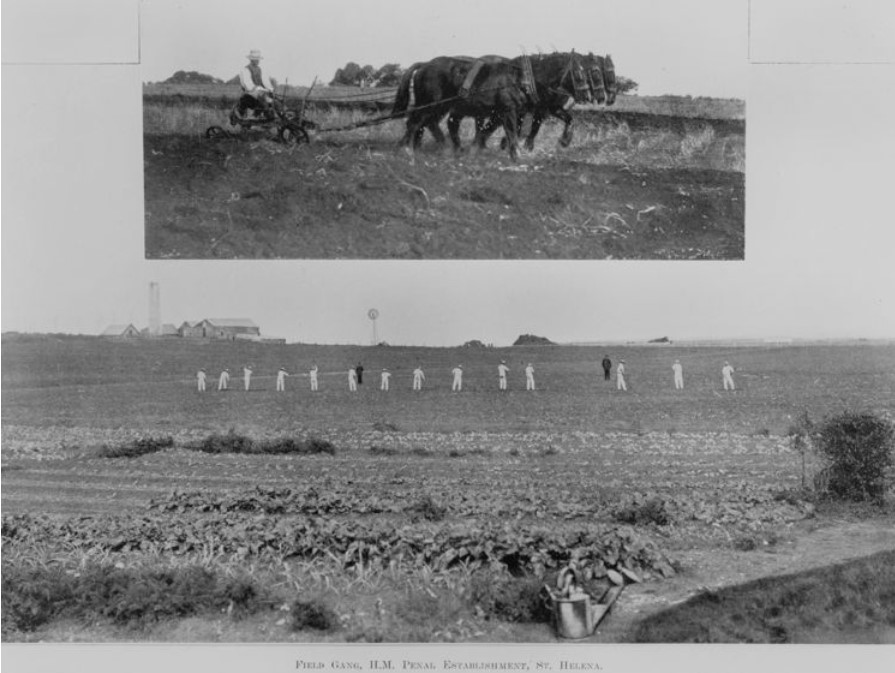

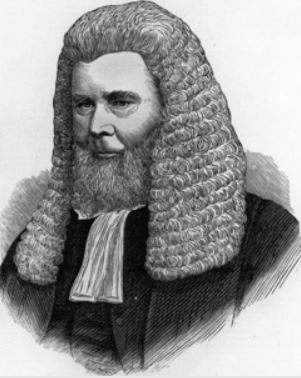

From left to right: Edward “The Snob” Hartigan and James “The Wild Scotchman” McPherson, fellow inmates of young Thomas Carey at St Helena Island. Judges Blakeney and Lutwyche, who each sent Carey to prison at St Helena.

Carey’s own infractions at the time were minor – he loitered at his work and had his tobacco stopped for a week, then neglected his work and spent a week in solitary on half rations. He also gave evidence in support of Hartigan in a dispute over who was responsible for a series of sexual assaults on a young prisoner.

The killing of Chevalier – Dalby, 1870.

In 1870, Carey was a free man. He returned to the Darling Downs region in search of horse training (and possibly stealing) work. He had hopes of working again for Samuel Moffatt, a station owner near Dalby. Moffatt owned a champion racehorse named Chevalier that was much favoured for the Christmas racing season. On arriving at Moffatt’s station, Thomas was informed that his services were not required, and that another man would be looking after Chevalier. Having travelled a long way, and having had his hopes dashed rather harshly, Tom Carey made some incautious remarks around the station to the effect that Chevalier would never run another race – he swore would cut its throat or poison it.

Carey headed back to Dalby and was promptly suspected of stealing a horse from Andrew McKenzie at Daandine along the way. He was duly detained and charged, but by 24 December 1870, no evidence could be found to implicate him, and he was free again.

Six days later, Chevalier was found dead – poisoned – in his stall at the Dalby Racecourse. It was the day he was due to compete against Timothy Howe’s two horses for a nice, rich purse. In fact, Timothy Howe’s horses – Nightshade and Tippler – were the only other horses running for the prizemoney. Any competition Howe might have faced had just been eliminated. Suspicion quickly fell on Thomas Carey, now sporting the moniker Tom the Devil, who had been loitering around the racetrack.

It transpired that Tom the Devil had approached Isaac Grounds, Howe’s trainer, and Howe himself, asking for a chunk of the prizemoney if he could prevent Chevalier from coming to the post. Accounts of who initiated and authorised the dastardly plan varied, but it seems all three men were involved.

Thomas Carey, Timothy Howe, and a jockey named Robert Reville were arrested. Isaac Grounds gave prosecution evidence against a furious Carey. The prosecution offered no evidence against Reville, Howe was acquitted, and the whole of the blame was placed on Tom the Devil’s shoulders. When asked by Judge Blakeney if he had anything to say, Carey was indignant. He stated that Grounds had been involved in the plot to kill the horse, not Howe, and that his defence lawyer had not consulted him about the strategy they would take. Judge Blakeney explained that he could not reopen the case, and characterised the crime as cowardly and dastardly. Thomas Carey received five years in Brisbane Gaol.

Carey arrived at St Helena in August 1871, but was forwarded to Brisbane Gaol in October 1871 to complete his sentence. Why this happened is not shown in the Register, but other prisoners who had been sent to Brisbane from the Island had either been unmanageable or too unwell to remain. Carey does not appear in the punishment books of St Helena at the time, so it may have been his health. He had gone from “stout” of build to “slight,” and was noted as having weak eyes.

A short visit to the Millchester region, 1876.

Once his five years had been served, Carey looked for work up North. He was too well-known in the Downs to continue any kind of career there – legal or otherwise.

The minute Carey arrived in a new town, horse owners became nervous, and with good reason. In late 1876, Carey was arrested for stealing a bay mare belonging to Andrew McIntyre, of St Ann’s station. He protested that he had bought the mare from another party, but McIntyre and his manager Bell testified that the mare had never been offered for sale.

“Thomas Carey, alias Michael Murphy, alias Tom the Devil, was sentenced to three years. I mention this gentleman’s aliases, as I have no doubt some of your readers will remember the owner of them, and feel thankful they are for some time safe against a visit from him.”

The Brisbane Courier’s Millchester correspondent, April 1877.

Tom the Devil is shot by police at Brisbane, 1880.

In early February 1880, the freshly liberated Thomas Carey was living and working at the Pine River under the name Tom Burrum. He took a day off to visit Brisbane, and returned the following day with a horse and some other articles. Meanwhile, at Taringa, Edward Sydney Cardell came home and found that his house had been burgled and his horse was gone.

On 22 February 1880, Constable O’Neill, who had tracked Cardell’s missing horse through its brands to the Pine River district, approached Thomas Carey at South Pine’s Clyde Hotel, and called upon him to surrender. The prisoner again hooked it, or more correctly perhaps, bolted, and O’Neill shot Carey in the leg.

In March 1880, Tom the Devil, still on crutches, faced Justice Lutwyche in the Supreme Court at Brisbane on a charge of horse stealing. He denied the charge in an unconvincing manner, and seemed more interested in threatening to prosecute Constable O’Neill for attempted murder. The jury, after the usual brief deliberation, found him guilty. Justice Lutwyche deferred sentencing, as Carey wished to call Dr Hobbs to make submissions on the effect of another term of imprisonment on his health.

Dr Hobbs deposed that, leg wound notwithstanding, Thomas Carey was in poor health. Hobbs had treated Carey for the last two years, and the prisoner had served three separate terms in ten years. Carey was several stones underweight, and time in prison had gradually wasted him away. Carey would, Dr Hobbs opined, be alright if he was able to work, but further imprisonment would endanger his health at least in the short term.

Justice Lutwyche characterised Tom the Devil as an incorrigible, and said he had no hope of reforming him. He gave Carey ten years’ penal servitude as an example to others who might be contemplating a criminal career.

The St Helena records show that Thomas Carey was discharged from prison on 21 March 1890. He was 42 years of age and had spent 20 years of his life behind bars.

Image credits (in order displayed):

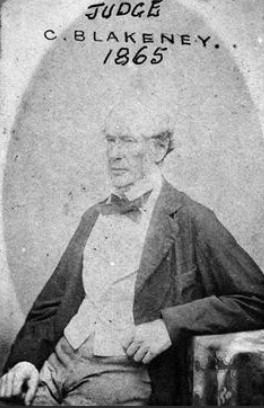

Citations: