Newspaper stories of the Plough Inn era.

The Wild Scotchman not apprehended at Milstead’s.

A young man who, for more than a twelvemonth past, has been peaceably occupied as storekeeper on a station in the district, was captured at Milstead’s as Macpherson, by Mr. Sub-inspector Appjohn and his men, and in spite of the remonstrance of Mr. Milstead and others, was kept all night in “durance vile.”

The unfortunate victim being several inches shorter than the Scotchman, narrow across the shoulders, bald headed, and decidedly mild, may take the mistake for the stalwart bushranger is no small piece of flattery.

[Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 27 December 1865, page 3]

A good race day (apart from a massive jewel heist, a death and a serious injury).

On Monday evening last those high and honourable men the stewards of the Dalby Races, were assembled in solemn conclave to make final arrangements for the races, and with them were gathered the elite of the sporting community. The meeting, according to custom, took place at Milstead’s. A few days before a couple of travelling jewellers took a room in the same inn, and displayed to the wondering gaze of the Dalbyites, watches, rings, brooches, &c., of great value and beauty, as the owners of them said. These, at night, were carefully packed away in a wooden case, and the owners say were worth £1500.

Well, during the race meeting the owners locked the door of their room, and left the box of jewellery, as they thought, secure. So they say; at any rate, they came back, the door is opened, the box is gone, and the jewellery. Who shall tell of the jewellery; Haley, the blacksmith’s shop had been opened, and next morning the box without its contents was found in the swamp, and apparently been opened with a black-smith’s rasp. Men who have met with such a loss are to be pitied; but it was very careless on their part in a place of public resort and on such a public occasion, to leave property so removable and of such great value so slightly protected. At present there is no clue to the perpetrators.

Our annual race meeting went off in many respects very well. Some of the contests were very good. The hurdle race was particularly good, the horses taking the leaps in a really splendid manner, and was pronounced by all the gentlemen present to be one of the best contested races they had ever seen. Unfortunately, in one of those rushes from one hurdle to the other, which is seen at any race of this description, the horse of Mr. Bryant and that of another gentleman came into collision with each other. Both riders were thrown, and Mr. Bryant’s grey, a strong grey, trod on his rider’s head. Mr. Bryant was able to walk when he got up, but soon afterwards had to be removed from the field, he was taken to the Caledonian Hotel, at which place he died about one o’clock the same night. I believe the immediate cause of death was internal haemorrhage, caused by his horse treading on his head. The deceased gentleman was for some time sheep overseer at Burncluith, and was in his 47th year at the time of his death. A magisterial enquiry was held on the ensuing morning, of which I will send further particulars next week.

A young man was kicked by a horse, and had to be carried away insensible. He was very severely hurt, but not fatally. It is very unfortunate that scarcely a race meeting taken place without one or more of these distressing accidents occurring, which go far towards destroying the pleasure otherwise to be derived from them.

A number of amateurs, consisting of some of the leading men here, gave an entertainment on Tuesday and Wednesday evenings. The pieces were played well throughout, and gained great applause. Good houses were obtained both nights, and the style of playing was far above that generally achieved by amateur players.

[Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld.: 1858 – 1880), Wednesday 3 May 1865, page 3]

Wanted: more blacksmiths and fewer cattle duffers (and loafers).

We have one blacksmith fond of a drink, but not of his smithy, and another fond of his smithy, but not of drink, employing many men and deservedly making money fast; but we want more blacksmiths, several more; and we want wheelwrights and a barber, badly. Mechanics are paid 12s per diem, labourers 8 s; shoeing a horse 10 s; and everything else in the same proportion, or about 100 percent, above Brisbane rates; not excepting nobblers and beer, and other refreshment.

We have loafers, and horse and cattle duffers, and large stock-holders without land; and men with an acre or two, with hut and stockyard, and maybe a few milkers and working bullocks, who brand calves by hundreds, and who rove about day and night upon blood horses, booted and spurred, like unto the borderers of old, dauntless and fearless, here there and everywhere, upon every body’s lands, and among everybody’s herds; defiant and safe, under the protection of their patron saint, St. Clair who, is doubtless you are aware, was a highly respected chieftain of cattle lifters, or rievers, or drovers, or something of that sort, in the Highlands or Islands of Scotland, and who, consequently, also have none to make them afraid.

[Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 19 April 1865, page 3]

Don’t tell Mr Milstead when to go to bed.

Yesterday morning, Mr. Milstead, proprietor of the Plough Inn here, was brought up in custody at the Police Court, charged with using profane language near a public street. After examining two witnesses, the P.M. dismissed the case, on the grounds of insufficient evidence.

From the evidence it appeared: the sub-inspector was sent for, as there had been some disturbance. On his arriving there Mr. Milstead was on the sofa on his verandah, perfectly quiet, and everything seemed quiet about the house. On the sub-inspector ordering him to go to bed, and threatening to give him in charge if he did not, Mr Milstead retired to his room, but coming out again shortly, was again threatened and finally given in charge by the sub-inspector.

Certainly, the charge was one of the most trumpery for which a respectable person ever had to, pass a night in the lockup, and it does strike many of us Dalbyites as strange that the sub-inspector should come to any man’s house, and after making whatever disturbance there was, take a man into custody because he insisted an pleasing himself at what time he should go to bed.

[Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld. : 1858 – 1880), Wednesday 29 March 1865, page 3]

School’s out – Black Harry’s getting married!

This was Wednesday last. I had heard the school-bell twang its “come to school,” as I walked along, and was in haste to see the youngsters “tit-tat-toe, like jolly butcher boys all in a row,” in the school playground. Just as I was turning the corner of the “acre of freehold land” on which the school is placed, a load hurrah resounded in my ears, and I beheld the “guileless multitude” of children running helter-skelter to their homes.

Had I not just passed the Town-Clerk’s office and beheld it in its usual place, I should have anticipated that the venerable edifice had come to its promised end, and that the “kids” were also hurrahing in anticipation of the evening’s lark; but I knew this could not be so: so, turning to a chubby-faced urchin who was running in the direction of the “Caledonian,” I asked what was up; he replied, still running, “There ain’t no school today. Master’s gone to Black Harry’s wedding;” and he was out of call. Upon prying about the premises, I found the schoolroom topsy-turvy, the desks and forms removed, and only one man present (who certainly was not the schoolmaster) engaged in sweeping out the place and preparing it for a gala of some sort.

“What’s up?” I repeated; when I was informed that “Black Harry,” whoever he is, had been married that day; that the schoolmaster was gone to the wedding-feast, and he was preparing the schoolroom for the wedding Ball in the evening. “Indeed!” said I; hardly knowing what to say next, and looking, I dare say, rather surprised. “Oh, yes,” rejoined the man; “We often have Balls here now. Subscription Balls, they calls ’em; but this is a real wedding ball! and no mistake.”

I waiting for no more; but finding my errand bootless, I passed on to Bunya-Street, and soon came in sight of Sidney’s Bridge, over which I passed in safety (thanks to the fates, and not to my own skill), and found myself before the palatial “Plough Inn, by J. Milstead.” Being a little vexed at my disappointment at the school, I entered “the Plough,” and while sipping my usual consoler, had time to pry a bit. What I saw concerns the future; what I heard tempted me to pay a visit to the post office in an adjoining street. On arriving at the locality, I found the office closed, the officials being at dinner.

[Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Thursday 5 May 1864, page 4]

See the big men run!

R. H. D. White, manager of the Bank, challenged Mr. Milstead, of Dalby, for 100 yards, and both gentlemen being pretty ‘lardy,’ the race excited much amusement. Mr. Milstead came in by a ‘head,’ and notwithstanding the pumpkins they carried, they nearly equalled Deerfoot in lightness.

[North Australian (Brisbane, Qld. : 1863 – 1865), Saturday 2 April 1864, page 3]

Dogs everywhere, money scarce and the hazards of being a postman.

The streets now being defined – the different buildings are brought prominently into view, the number of which astonish even the residents. Bark huts have given way to more substantial erections, which will bear favourable comparison with any buildings out of Brisbane, and many of them would not disgrace even the leading streets of the metropolis. The first deserving of notice is Milstead’s handsome and commodious hotel. There are three blacksmith’s shops, several butcheries, a good bakery establishment, a chemist’s shop recently opened by an enterprising gentleman of the name of Jones from Victoria, a national school, &c., &c.

I must not omit mentioning the extensive range of buildings belonging to Mr. Gayler, of the Criterion Hotel, who has recently added to his premises a detached billiard room, well-ventilated and lighted; the billiard table is new, and of a very superior description, imported to order; thus an opportunity is afforded for enjoying a pleasant hour’s amusement. I know only of two instruments which bring all the muscles into play, and they are the spade and the billiard cue. We have an Amateur Dramatic Society, a music hall, &c.

Every street swarms with dogs, disturbing the repose of inhabitants at night by incessant barking and howling, – by day endangering passengers in the streets, by rushing upon and snapping at the heels of horses. The best remedy for the nuisance is by raising the registration fee to 10 s., or £1; and I hope some member of the Legislative Assembly will move for the introduction of a short bill to that effect.

Winter has set in with severity, and for several days last week the cold was extreme. Rain has fallen in deluges in all parts on this side of the range. Robinson, the Toowoomba and Dalby mailman, also reports that he had, on his last journey from Toowoomba to Dalby, to urge his horse for several miles through water higher than the animal’s kneels, sometimes rising to the saddle-flaps. The occupation of a mailman is certainly no sinecure.

General business continues excessively dull. The prevailing epidemic is “tightness of the chest.” Money is scarce, producing at times a difficulty in speaking freely. A capitalist having a mania for building, would soon realise a fortune in this town.

[Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1861 – 1864), Saturday 1 August 1863, page 4]

Race Day festivities – it isn’t a party without a German band.

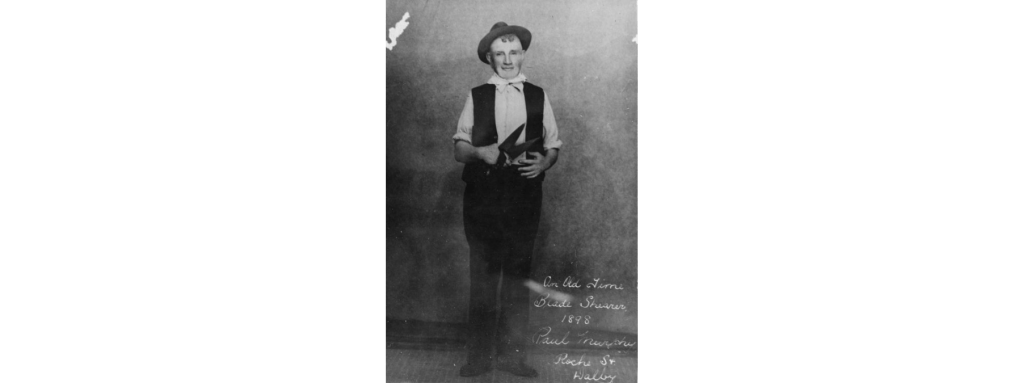

A German band is to entertain us between the acts on the course, and Joe – not old Joe – but Joe Milstead of the Plough Inn, having at last got into his new house, Mrs Joe inaugurates the auspicious event with a ball, under the patronage of the stewards, and great are the preparations in town by the young belles of Dalby to come out in proper style.

[The Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1861-1864) Friday 22 May 1863, Page 2.]

“Get up, you bloody fool, you’re robbed.”

Mary Walsh was indicted for stealing two bank cheques, the property of William Foote. The evidence showed that on the morning of the 3rd December the prosecutor, who was very drunk, “found himself” in the house of the prisoner, at Dalby. He had previously to the morning in question in his possession a portmonnaie (wallet) containing £36 or £37. He last saw it safe in his possession the day before. He had a cheque drawn by Mr Thorn in favour of John Dillon. He did not get more than one cheque of Mr Thorn’s from John Dillon, as far as he believed. When he awoke in the morning the woman said, “Get up, you bloody fool; you’re robbed.” He then found that some of his money was gone, but the purse was left. All the cheques were gone.

On cross-examination by the prisoner, the prosecutor would not undertake to swear that he did not give the money to her when he was drunk. In the morning the prisoner passed the cheque to a publican named Josiah Milstead. The cheque was identified by Mr Thorn and Mr Dillon as the prosecutor could neither read nor write. The defence set up by the prisoner was that the prosecutor had given the cheque to her to buy clothes for herself, on condition that she should leave her husband and live with him. As she would not do so, he gave her in charge. Verdict – not guilty.

[Courier (Brisbane, Qld. : 1861 – 1864), Tuesday 20 January 1863, page 2]

Outwitting the Wild Scotchman on the road to Dalby.

The Brisbane “Daily -Mail” has recently published some interesting accounts of early days in Queensland, and the following letter from Mr. W. Ruddle, of Fortitude Valley, contains much that will be found of local interest. Mr. Ruddle writes: —

Your tales of “Early Days” wake up events of long ago I had forgotten, especially those of the Wild Scotchman. I think he gave no one in the Maranoa more trouble and anxiety than he did me, as he seemed determined to have my racehorse Premier, and I was determined that he should not. It is rot for people to crack this sort up as heroes because they give away to people who have befriended them, or in hopes of winning their sympathy and help, money they have easily obtained and cannot spend on themselves. That they have real or fancied wrongs is no excuse for robbing a score of people of what perhaps they can ill-afford to lose, and cause worry and anxiety to hundreds of others from whom they have received no injury whatever.

I had been living a few years at Tingan, now called Blythdale, and Euthulla, and had gone overland to Sydney and bought a thoroughbred colt when the news came that the mail had been stuck up by a man who called himself the Wild Scotchman. I had Premier running out with a quiet mob. of horses a few miles up the creek.

One day, Owens, a bullock driver, came and told me that as he was up the creek, he saw a man trying to catch my horse. Owens went up to him and asked him what he was doing. The man answered (at the same time pulling out a revolver) “I’m the Wild Scotchman, and I’m going to have that horse.”

Owens was a great big resolute fellow, and would have done anything for me, but under the influence of the revolver he talked very mildly and begged him not to take the horse, as it did not belong to a swell, but a young chap working on the station. “Well,” said the Scotchman, “I won’t take him now, but I know where to come for him when I want him.”

I got Premier in and put him up the back creek and hobbled a couple of quiet horses to keep him company. When the Roma races were coming on, I gave him a rough bush training, plenty of walking exercise, and a few gallops on the sand hill in company with a black colt called Phantom.

The day before the races I took the horses to Roma, where I had secured a stable from Charlie Ahern, near his pub. All the station hands that could get away went in to the races. The place was full up, but we managed to get a room to put out things in. Most of our fellows slept on the veranda. I slept in the stable. The horses were in two large stalls, shut in by a pair of heavy box sapling rails. The door was fastened inside by a hobble chain slipped over a staple with a wooden peg through the staple.

During the night or early morning, I was awakened by someone trying to force open the door. I jumped up (I had not undressed), and sang out, “You can’t come in here, there are racehorses here.” He said, ” I’m coming in,” I said, “I’ll brain you with a rail if you do.”

I took a rail from the stall and swung it over my shoulder to be ready. The door creaked – it was a rickety old affair – presently the fastenings gave way, the door banged back, and a tall man stood in the doorway, clear and sharp in the bright moonlight. I swing the rail with all the force I would, and took him a slanting blow across the forehead. His head gave way before the blow; it was like striking a lump of butter. I thought I had killed him, as he fell with a thud and lay quiet and motionless on the ground, and his cabbage-tree hat went rolling off.

Two men stepped out from the shadow of the stable. One said, “‘You’re a nice fellow to hit a man like that.” I said, “Good job for him I left my revolver inside or I would have shot him instead.” Then I yelled as loud as I could, “Help, help; Euthulla, Euthulla.” In a jiffy half a dozen of our fellows came running up asking what was the matter.

I said, “This fellow broke into my stable and I knocked him down with this rail. I believe I’ve killed him.” “Serve the so and so right; let’s jump his inside out,” was the response. ” Oh, no,” said the strangers in a much quieter tone than they had used before, “we’ll take him away all right.”

They put his hat on his chest, one got between his legs, the other put his arms under the armpits and carried him away. I was very nervous in the morning thinking perhaps I had killed someone and there might be a row. But the race day went on and with its excitement I forgot all about it. In the evening a couple of us went round quietly, inquiring if anybody had got hurt. No one seemed to have heard of it, and we kept it very quiet.

A good while after, when it had passed out of my mind, a man said to me, “Hello! knocked anybody down with a rail lately?” I scanned him very suspiciously, and said, ” Well, I did knock somebody down once, but I don’t know who it was.” He said, ” What, don’t you know who it was?” I said, ‘”No.” He stooped down and said in a low tone, “The Wild Scotchman.”

We never thought of the Scotchman just then as we had the information that the Scotchman was at Mount Hutton for certain. I think the yarn was spread to throw us off our guard. He had friends at Roma that always kept him well posted as to what was going on. But after this I was afraid to turn my horse out, and I knew I should get nothing soft at the hands of the Scotchman.

Mr. Wm. Bassett, who was at once my friend and master, proposed that I should keep Premier in the paddock. The fence was strengthened all round. At the entrance gate was a building called the barracks— half in and half out of the paddock. In fact, it formed a part of the fence. The little wicket gate was right under one of the windows, and the long gate for vehicles next to it, so that no one could go in or out without passing within a yard or two of the window.

I was to sleep in the room looking out on the gates, with a loaded rifle. My boss said : ” If he comes in let him go, but if he tries to lead a horse out, and you let him, it will be your fault. Shoot his horse.” “No,” I said, “I will not shoot his horse I’ll shoot him.”

There was a pair of sawyers camped in the scrub a few miles from the head station. One of them was a blue-nose; he knew all about farm work. We got him a scythe, and he made me plenty of hay from the blue grass between the scrub and creek, from which they kept the stock. They could never do enough for me, and would never take a penny for it. I did them a good turn when I came on them—strangers lost in the bush—and their gratitude was unbounded. But for this hay I could not have kept my horse in the paddock, as the feed in it was always scarce, and in those days there was no other feed to be got up there. They were sawyers without any saws, sawpit or logs; in fact, they were making “grog” for the pubs around, but they were very good to me. I would not say a word about it now, but it is so long ago they both must be dead.

One day Mr. Bassett came to me and said “I hear for certain the Scotchman vows he will have your horse. When I was down at Limestone (Ipswich) I had a good look at all their horses, and not one is in the same class as yours (Mr. Bassett was a splendid judge of a horse). Have a run down. Take Myall Creek (Dalby) as you go. You can win a lot of money. I’ll give you three or four months’ leave, only keep Premier out of the Scotchman’s hands until the time comes for you to start.”

Everybody was dinging into my ears that the Scotchman would have my horse, until I was ready to shoot him. at sight. One day Mr. Watts, a boss of Government roads and bridges, brought a racehorse named Rocket up to Roma, and challenged to run anyone a mile and a half or two miles, for any sum up to £500. I got J. McDowall, a younger brother of our late Surveyor-General, to go down and make a match for all he could get on. He was to come back during the night and let me know.

Now Jimmy McDowall, I believe, saved the Scotchman’s life that night. I was a real good bushman; had been used to droving (expecting cattle to rush), also to sleeping out when the blacks were bad, so that I never slept so sound but that I knew where my horse was feeding and all that was going on round me. In the night I was aroused by the tread of a horse coming up to the gate. In a moment I was up, with my rifle on the windowsill. There was no moon, but it was a clear night. A horseman rode up to the gate, and I sang out, “Is that you, Mac.”— (thinking it was McDowall)—”is that you, Mac? Are you not a fool to play these tricks?”

The horseman leaned over, opened the big gate, rode in and down to the house. I. began to think it must be the Scotchman, because McDowall would not go to the house unless he had some message, as his bed was alongside of mine.

In about a quarter of an hour the horseman returned. I jumped up as he came to the gate. I took a steady aim at him, and noted that he had no led horse. Again, I sang out: “Mac, if that’s you, why don’t you speak?” I was in real agony for fear it was my comrade, and I should shoot him. Looking at the window he must have been able to see the rifle barrel pointing at him. My finger trembled on the trigger, but I let him pass.

First thing in the morning I went down to the house. They told me he rode up to the veranda, so close that his horse pawed the veranda; They watched him through the blinds. He turned his horse, rode down along the creek, then into the creek, back again, and down into the creek again. He seemed puzzled. Then he came back to the house again.

Mr. and Mrs. Symonds, relatives of Mr. Bassett, were living then. They recognised him from descriptions as the Scotchman. When he went back through the gate, they expected every moment to hear my rifle ring out, and my rifle would have rang out had I been as certain as they were, or had he led a horse out—not for the thousand pounds that was then on him, but for the safety of my property and the constant worry he was giving me.

I can easily understand why the Scotchman was puzzled that night. Coming up from Roma the Bungil Creek is on the right hand, but just before getting to the new head station it has a peculiar turn. When he went through the gate down to the house and on to the creek, the creek would seem to be running on his left hand. On a moderately dark night, it would puzzle anyone.

After breakfast as I was cantering along the road to Roma I met Gilmore and his black boys tracking. ” Hello.” I said, “on the Scotchman’s tracks?” ” Yes,” said Gilmore. “Come along with me,” I said, “and I’ll put you some miles nearer to him. He was at Euthulla last night, and I watched him off towards the Bungeworgorai.” Away we scampered, and I put them a few miles nearer to him. That afternoon they just missed catching him. The boys tracked him to his camp, and found his spirit lamp lit, with his tea hot and food not touched; but the bird had flown. He must have seen the troopers before they saw him.

As the time drew near for me to start for Dalby to train for the races, on my way to Ipswich I believe I nearly put my foot in it by being extra clever. I went down to Roma where I knew the Scotchmen had friends that kept him acquainted with all that was going on. So I went all round the town and bade all good-bye, saying, that I was just going to start with Premier to race at Dalby. I then went back to Euthulla and started coaching out some scrub cattle from the scrub on the Dividing Range. After a couple of weeks, I went down to Roma again.

“Hello,” they said, “thought you were at Dalby by this time.” “Oh, no,” I said, “not going; altered my mind.” After spinning this yarn, I went back to Euthulla and started next morning for Dalby. I did not take the main road. I was a first-rate bushman, and I kept at the back of Wallumbilla, across the Bendemere run. I could not go wrong; I had the main road on my right and all the creeks running down to the Condamine. I took plenty of rations, so that I never went near a house until I rode into Milstead’s Hotel, at Dalby.

I had a packhorse here which I drove with Premier, and I rode a spirited but very handy mare I had won several races with. I never left the horses night or day. At night I camped anywhere I found water and grass -hobbled the mare, hung my things in a tree, took a blanket, a bridle, and revolver, and laid down close to the horses, and dozed off. When the horses moved off, I quietly took my blanket and laid down again close to them, and so on, until morning, when I caught the mare and quietly walked the horses back to my camp.

I never put my hand on Premier from the time I started until I had him in Milstead’s yard. I did this for fear the Scotchman might catch me unawares. He could not catch the horse, and even if he did he could not ride him, for Premier would buck a hurricane, and the Scotchman, though a splendid bushman, was no horseman. He could ride a quiet horse, but that was all. In this way I expected to get the best of him should I be unfortunate enough to meet him. Once before when in a fix by suddenly meeting a man who was going to play up with me, I hit my horse with the spurs and bumped into his horse and neatly knocked him out of the saddle. After I had bumped him about a bit he was very glad to scamper off. I got no more threatening messages from him. I am a poor revolver shot at anything like a distance, so I intended if I met him to hit my mare with the spurs. She would then fly all over the place, and I would bump against his horse and shoot in the scramble.

But to continue. I got through a lot of rough country, and in a few days struck a ration road. After a while I met a man on horseback, and just as he was leaving me he said: “The Wild Scotchman is ahead of you.” I said, “What sort of a horse is he riding?” He said, “A roan. His horse was knocked up, so he went up to the station (I forget the name just now), yarded the horses, and took the roan. It was a bit flash; did not buck, but just jumped about and nearly threw him.”

About an hour later I passed a station a little off the road. A track branched up to it, but I kept on the road. In about another hour I was jogging along when I heard a horse cantering behind me. I looked around, and saw a man on a roan horse cantering on the grass beside the road. He got close to me before I heard him. It gave me an awful fright, but it was one of those savage frights that makes one fit for anything. In a moment I had my revolver out. I jumped my mare to the side of the road so as to put him on my right hand. I wheeled the mare with the intention of cannoning into him as he came up. But the man on the roan had a bigger “start” than I did.

As I faced him, he pulled his horse right on his haunches, threw up bis right hand, and sang out, “I’m the storekeeper from the station behind.” I said, “Are you?” still keeping my revolver ready. He said again, “I’m the storekeeper.” I looked at him. Although dressed like the descriptions given of the bushranger, he was shorter, stouter, and somewhat older. I said, “I took you for the Scotchman, as you are riding a roan.” He said, ” I knew you did as soon as I saw you pull out your pistol.” We jogged along the road, and yarned, and laughed it off, and, as already stated, I got safe to Dalby.

Ten or twelve years after a man came into my bar with two children, between 12 and 15 years old. Pointing to me he said to the children, “That is the man who was nearly shooting me.” “Oh, no,” I said, “you must be mistaken; it could not have been me.” “Oh, yes,” he said, “don’t you remember that when you were going to Dalby with your racehorse you took me for the Scotchman.” I held out my hand; we had a hearty shake, compared notes, had a drink together, and parted forever. There is no romance about what I have written, every word is true.

[Western Star and Roma Advertiser (Qld. : 1875 – 1948), Wednesday 20 January 1909, page 4]