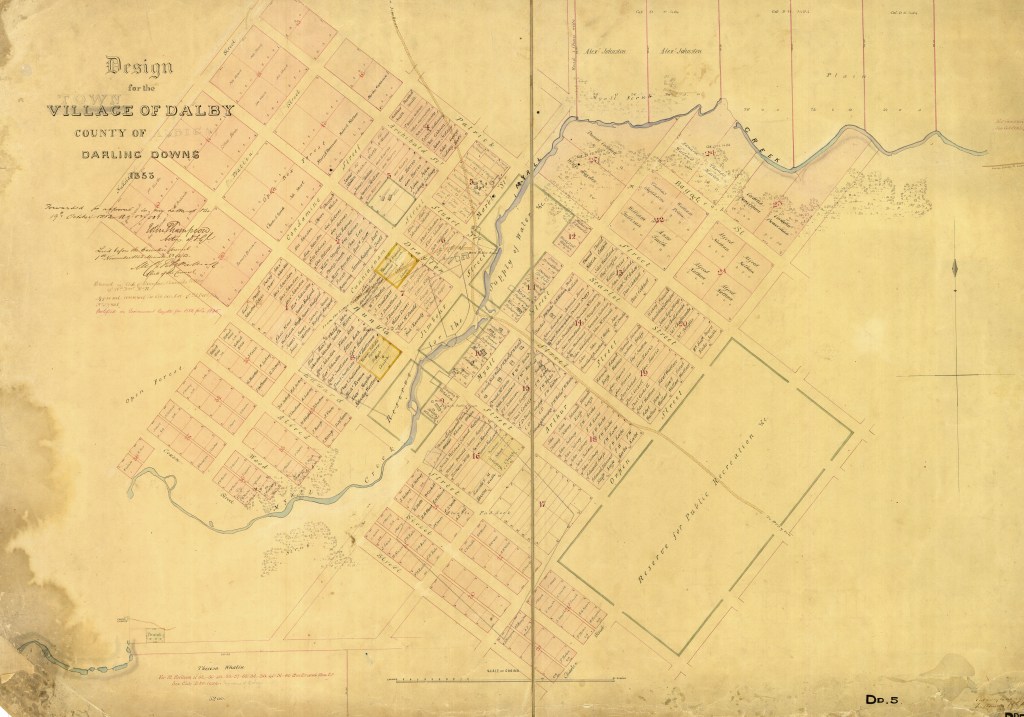

Part 1 – The early days of Dalby, and the creation of the Plough Inn.

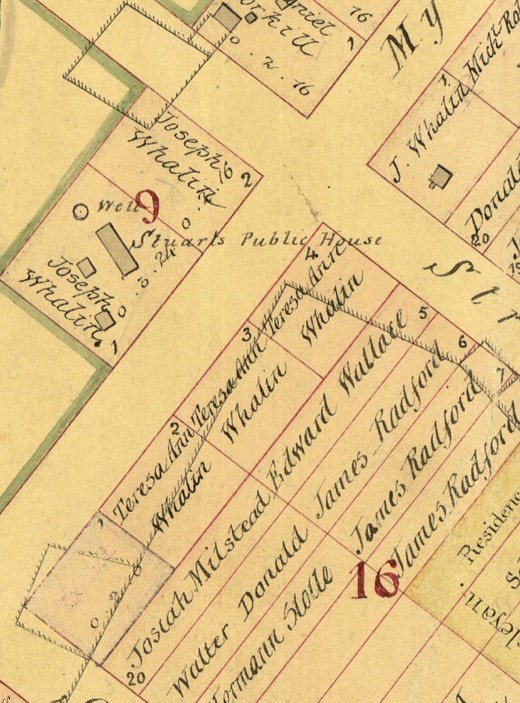

This was the beginning of the town of Dalby in 1853 – a plan that showed the selections of land made by the township’s earliest European inhabitants. All of the storied names of 19th century Dalby are there – Charles Douglas Eastaughffe, future Chief Constable; Alfred Peter Gayler, hotelier and civic activist; and John Sidney and F.W. Roche, noted merchants. There were also three people named Whalin, who selected vast amounts of land – Joseph, Theresa and Winifred Whalin – who, together with their neighbour, Josiah Milstead, made Dalby a destination for more than a decade through the Plough Inn, the biggest and finest hotel in the town.

Arriving in the colonies.

Theresa Anne Mackey (later Whalin, later Milstead).

Theresa Anne (or Anne Theresa – she loved to swap her given names) Mackey was born in Johnstown, Dublin to John Mackey and Anne O’Meara in 1822. By 19, she had trained as a house servant, could read and write, and was headed to Sydney in the New York Packet. She was brought out to Australia by John Miller under the care of Andrew Kerr and wife. The Andrew Kerr in question was probably the wealthy Scottish station-owner at Bathurst. Kerr had married Elizabeth Livingstone in 1837, and had a young family, largely composed of boys. [Kerr was also involved in a violent encounter with the indigenous people of the area.]

Anne Mackey may have developed her superb management and catering skills in her work for the Kerr family. The family regularly entertained colonial grandees, and there was a large station to run. How long she remained with them is not recorded but by 1846, Andrew Kerr had lost his wife and two of his sons, and Anne Mackey was residing in Sydney, and had a daughter.

Anne’s daughter Winifred Whalin was born in Sydney in March 1846. Winifred was acknowledged as the daughter of Joseph Whalin, although Anne and Joseph would not marry until April 1854, by which time they were settled in the Darling Downs. The couple had selected a great deal of prime residential land in Dalby, as had their eight-year-old daughter, whose name was on the Dalby town plan as the owner of a large block of land on the corner of Scarlet and Myall streets, a few blocks up from her parents’ holdings.

Josiah Milstead.

Josiah Milstead was a native of Kent, England, and was four years younger than Theresa/Anne Mackey. In 1847, while still a teenager, he was charged with stealing. He had been working for pawnbroker Thomas Pacey Birts and was found with assorted items that had disappeared from the shop.

Milstead pleaded guilty at the Old Bailey, and was sentenced to seven years’ transportation. He had to wait in the Northampton Gaol until 1849 before being sent to Moreton Bay via the convict exile ship, Mounstuart Elphinstone.

Unlike many of his shipmates, Milstead did not paint Brisbane Town red once he landed – he set about the business of making himself useful. His entry in the English Criminal Registers noted that he could read and write well, skills he made good use of in the colony.

He spent a couple of years in the Logan area, advertising for lost stock on behalf of local station owners, before relocating to the new township of Dalby. He selected Lot 20 on Edward Street, just behind the five properties reserved for the Whalins on the corner of Bunya and Myall streets.

The Ploughman’s Arms, Dalby.

In November 1855, Joseph Whalin advertised his two bullock teams for sale, in excellent condition, and accustomed to travelling, “having no further use for them, being now Innkeeper in Dalby.” A Londoner in his late thirties, he must have had a knack for making money, because he was able to buy the one-story Stuart’s Public House located near the Myall Creek, on the corner of Bunya and Myall streets.

The pub was christened the Ploughman’s Arms Hotel by Whalin, and with his wife Theresa (as she now chose to be known) supervising the kitchen and accommodation, it became a magnet for squatters and workers on their way to and from Jimbour station. Dalby had fifteen public houses at the time, but in the words of Dalby old-timer, Thomas Chambers, only three “had any claim to dignity,” and the Ploughman’s Arms was one of them.

The Whalins enjoyed two successful years as publican and house manageress, and at the April 1857 Dalby land sales, Joseph made purchases amounting to more than £130. He renewed his publican’s licence on 06 May, and then suddenly passed away on 14 May 1857.

Mrs Milstead’s Plough Inn, Dalby

After the shock of widowhood, and the ordeal of the Supreme Court at Moreton Bay in Ecclesiastical jurisdiction, Theresa Whalin purchased another two roods of land at Dalby. Then she set about refurbishing the Ploughman’s Arms, (“on a scale of unprecedented splendour”), ready to trade under her own name and style.

Just how unprecedently splendid or otherwise the Plough Inn might actually have been, was revealed in a court case. One Smith somehow came to possess some of the contents of one Baldwin’s pocketbook after a night at the Plough Inn. Mrs Theresa Whalin was called to give evidence, and described her clients and the premises:

Smith and Baldwin were not particularly together. It is usual when a man “shouts” in a bush public-house to let it go all round. Smith did not “shout,” he had no money. He had spent his money previously. We always pretty well know that; he had ceased to call. Baldwin was not beastly drunk when he went to bed that night.

The parlour is at one end of the house. There is a way from that into the general thoroughfare and the room where Baldwin slept. I have four front rooms in my house. I have a cottage in the yard to accommodate lodgers. There was no one there that night. The last thing I saw of Smith he was beastly drunk laying on his face and hands against the water butt in the yard.

Theresa Whalin

Without the presence of a husband in the house, Theresa had to deal with disruptive bush drunks, manage the house, and also raise her daughter, who was what a later generation would call a “tween.” Mrs Milstead decided to send Winifred to board at Bellevue House (“near the marine baths and botanical gardens”) in Brisbane.

Bellevue House was run by Mrs Story and Miss Lister, and boasted a very ladylike curriculum:

The course of instruction comprises: English, in all its branches; Writing, Arithmetic, and Needlework, French, Music (pianoforte and harmonium), Singing, Drawing, Dancing, and Deportment, Geography and Astronomy.

Advertisement for Bellevue House, January 1858

Furthermore, the two educators promised that young Winifred would be in the very best hands:

Deeply imbued with a sense of their responsibilities, Mrs Story and Miss Lester assure all those who may entrust children to their care that their moral and religious training, their comfort, happiness and health will be strictly attended to.

Theresa Whalin sent Winifred to Brisbane in January 1858. In February 1858, Mrs Story and Miss Lester found themselves in court, facing assault charges brought by Winifred and her redoubtable mother.

It’s clear that young Winifred did not enjoy boarding school one bit. She ran away frequently and bridled at the discipline, her food and her sleeping arrangements. Other students distracted her from her prayers. Early one morning, local resident Mary Standon opened her door to a frightened and shivering Winifred, who sought refuge in her parlour. Mrs Whalin was contacted and came to Brisbane at once – quite a feat at a time before telephones.

Her mother had difficulty finding a lawyer who would take her sworn complaint, and remonstrated with a solicitor who kept her waiting. The resulting court case made a minor sensation, as Winifred gave lurid evidence of whippings, name-calling and stale butter. (Her evidence reads like something out of Jane Eyre, by way of Radclyffe Hall, and is extracted at the end of the post.)

The Bench was not impressed and put a halt to the case with the following statement: “We do not think it necessary to call for a defence, that the assault was justified and did not exceed the bounds of moderation in the manner the instrument or quantity of punishment, and that the correction of the scholar by the schoolmistress was not excessive.”

Theresa Whalin was mortified when Mr Rawlins (the lawyer she had consulted) claimed in open court that she had insulted him the previous day. Furthermore, the Courier had printed that assertion. The Editor of the Moreton Bay Courier, per favour of the North Australian, was given her version of events, and they show what an intelligent and formidable woman Theresa Whalin was:

Theresa Whalin could handle herself very well, but as a widow running a business by herself in 1858, she had to undertake her late husband’s work as well as her own. And bring up a daughter who did not take well to being sent away from home.

The solution to her troubles appeared in the robust form of her near neighbour, Josiah Milstead. He had an engaging way about him, a head for business and a healthy level of ambition. The couple married in April 1858, eleven months after Joseph Whalin’s passing.

The Milsteads of Dalby were ready to take the hotel business to new heights.

Next post – The Plough Inn, Dalby.

Winifred Whalin’s evidence in chief, February 1858.

Sources: