After travelling to Brisbane in February 1858 to support her daughter’s failed assault charge against a teacher, Theresa Whalin took stock of her life. She was a widow with a country hotel to run, a lot of land, and a wilful daughter to raise. There was another land sale afoot in Dalby in March, and Theresa thoughtfully purchased 52 acres at £1 per acre. One needed to shore up one’s holdings.

Neighbour Josiah Milstead was 32 years old, and smart and ambitious. A widow with a hotel, business acumen and a great deal of property was an appealing prospect. The two married on 6 April 1858 and set about making Milstead’s Plough Inn the finest public house in Dalby.

Milstead’s Plough Inn.

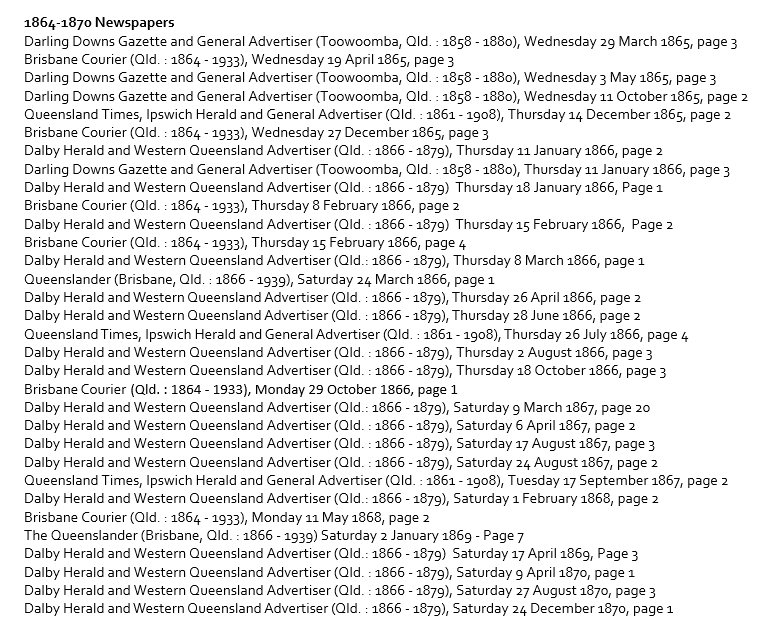

Josiah advertised for two bushmen to put up a fence to enclose the 52 acres of land, and in June, purchased his own 50 acres. He kept up the lost stock advertisements – a useful source of additional income. Then Josiah, who had a knack for writing advertising copy, began promoting “his” hotel in the Darling Downs Gazette.

In 1859, as Separation loomed, Josiah commenced regular advertising in the Darling Downs Gazette – both for his establishment, and for staff to work in it. The turnover of cooks, laundresses and house servants was extraordinary – probably because of high standards of the imposing Irishwoman known as “Mrs Joe.”

Contemporary accounts describe a meticulous and talented cook and caterer; “a lady with a good business head but an uneven temper.” Several years later, when embroiled in a dispute with a neighbour, it came to light that Mrs Joe was a person of imposing height and weight, who could certainly inflict bone-breaking injuries if she chose (she didn’t choose, mercifully).

When the Colonial Secretary stayed and dined at the Plough Inn, the Courier noted, “Mrs Milstead displayed her usual tact and good taste in the arrangements made for the comfort of the visitors. At 7 o’clock a large party sat down to a sumptuous repast. The tout ensemble of the table was all indicative of Milstead’s abilities as a public caterer.”

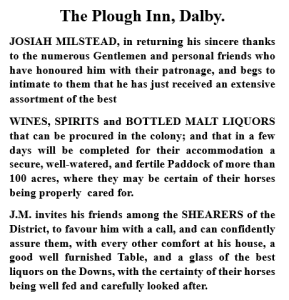

In 1861, His Excellency, Governor Sir George Bowen made his first visit to Dalby, and the Queensland Times was duly impressed: “On Monday morning his Excellency was invited to a public breakfast, which was served up in Milstead’s style, the whole arrangements being quite equal to those I have witnessed in the best English hotels.”

As a promoter Josiah Milstead had no shame. Two visits from Sir George Bowen in the course of four years prompted him to advertise in Pugh’s Almanac thus:

More than sixty years later, a Dalby old-timer recalled that Mrs Joe had “a great reputation as cook and manageress. Mrs Milstead was always entrusted with all public dinners, wedding festivities, etc.”

With a fine cook and manageress in residence, Josiah was free to become a Leading Citizen.

In the early 1860s, between Vice-Regal visits, Race Meetings, and floods, Josiah Milstead set about building a very large new hotel. Building materials, and indeed builders, were scarce in Dalby at the time, and this process took over a year. The Courier’s occasional Dalby correspondent reported the result:

I have seen no town in Australia present so extraordinary and even imposing appearance from a distance; its acres of flat low tenements, of the hay-stack style of architecture; all on one level, with a school of arts (a larger hay-stack), and Milstead’s Plough Inn, two stories high, towering above them without any background but the clear blue sky, reminds one forcibly of a picture of a town of India, or of a desert; and upon entering it, the wide roads, white paint, many sun-blinds and verandahs, and lots of Chinamen meeting your eye on every side, complete the illusion.

Affable Joe took part in all manner of civic occasions, from hosting the Race Day crowds (and their steeds), to personally conducting bridge-building works, to taking part in a graveyard-fencing committee (the local pigs were given to disturbing the eternal repose of those who had gone to a Better Place). He even took part in a 100-yard dash challenge with Mr RDH White of Toowoomba, the novelty of the event being that both gentlemen were “pretty lardy.” The “weightiest men on the ground” gave the event their formidable all, with Josiah Milstead winning by a hairsbreadth.

Mayor Milstead, and the beginning of the end.

Naturally, all of this civic activity could lead in only one direction – municipal politics. By the end of 1863, Josiah Milstead was an alderman, and in 1866, he was Mayor of Dalby. Unfortunately, 1866 was also the year that everything the Milsteads had achieved was also lost. The Inn, the marriage, the money – everything.

There was a “financial panic” in Queensland that year, and many a capitalist and speculator lost everything. Joe Milstead had taken out a lot of loans to build the imposing new Inn and struggled to repay in the difficult financial climate. Alfred Gayler, the Milsteads’ main rival in the Dalby hotel business, also lost everything. But there were other issues troubling the Milsteads of Dalby.

On 9 January 1866, Theresa Milstead was charged with wilful destruction of property belonging to her husband and was committed for trial at the next Dalby District Court sittings. Just what she did was not made public, and although a brief was delivered to the Crown Prosecutor, nothing seems to have come of the charge. The only criminal matter heard at the Dalby District Court’s March sittings was that of another fiery Dalby wife, Mrs Kim, who assaulted and stabbed her husband. She got fourteen days’ imprisonment. I suspect that the crime would have been dealt with a little more seriously had Mr Kim not been of Chinese descent.

In 1913, the Dalby Herald published a series of old-timer’s recollections, and included this tale in its history of the Plough Inn:

The downfall of the Plough Inn was associated with some remarkable circumstances. When Governor Bowen decided to visit Dalby, the event caused a great flutter, and the town turned out in buggies and on horses to meet his Excellency at Bowenville, then called the Long Waterholes, some seventeen miles from Dalby. Mine host of the Plough Inn insisted on joining the crowd, much against the wishes and orders of his wife. She was so annoyed at his disobedience that after his departure she took a bottle, and starting on the top storey (it was the only two-storied building in Dalby at the time), smashed every mirror in every room. Coming downstairs, she completed her work of destruction, as far as the mirrors were concerned.

Dalby Herald, 1913.

There is no evidence to show that any damage was done to the Plough Inn at the time of the Governor’s visits in October 1861 or November 1864. Journalists might have noticed if the vice-regal guests were being entertained in an unusually well-ventilated venue. Theresa’s malicious damage charge was laid in January 1866, and the only big Plough Inn event around that time was the Great Dalby Land Sale on 28 December 1865. If the great window-smashing took place, it may have occurred around then. Mrs Milstead was granted bail and would henceforth reside with her daughter and son-in-law (Winifred had married William Robertson in 1864 and lived at her Scarlet Street property).

Aside from suffering property destruction to a value exceeding £5, and the abrupt departure of Mrs Joe, Josiah Milstead lost his beloved sister Hannah in January 1866. She died at Bowenville near Dalby at the age of forty, following a long and painful illness. Hannah was his only family in Australia, and the loss must have been hard to bear.

One more blow was dealt by an unknown arsonist. Early on 29 January 1866, smoke was seen coming from a downstairs bedroom at the Plough Inn. Josiah rushed downstairs and extinguished burning bedclothes and a scorched table leg. Someone had thrown an accelerant through the window, and the footprint of a woman’s shoe was noticed outside. “There are good grounds for believing that the culprit is not unknown,” noted the Courier, a trifle ominously.

Nevertheless, Josiah kept up with municipal council campaigning, and was returned as an alderman in February 1866. The council met and installed him as Mayor of Dalby. Mayor Milstead soldiered on, convening a public meeting in April to prevent the District Court being abolished (it survived), and announcing an extraordinary election to find a replacement for Alfred Gayler, who had resigned due to financial stress.

Then on Monday 11 June 1866, Mayor Milstead tendered his own resignation, triggering another extraordinary election. A week later, he was placed in the Dalby lockup for protection. He was suffering, the Magistrates heard on Friday 22 June, from a delusion “that someone intended him personal harm,” and experienced “great terror.” I suspect that the person who intended him harm was not unknown.

The magistrates, friends and fellow aldermen who must have looked on Josiah’s downfall with sorrow, remanded him to the following week. On his next appearance, sureties were found for a good behaviour bond “to keep the peace towards others and himself.” For a time, Josiah could return to the Plough Inn, and assess the financial and emotional turmoil he found himself in.

Milstead struggled on for a month, until his behaviour became such a concern that his sureties withdrew. The Dalby correspondent of the Darling Downs Gazette reported the development:

“It appears he has been suffering from mental aberration, rendering him quite incapable of self-protection or minding his own business. As there were not two duly qualitied medical practitioners to give a certificate of lunacy, he was bound over to be of good behaviour, and on two occasions found sureties. Owing, however, to his eccentricities, the bondsmen deemed it advisable to withdraw, and so Milstead will be sent to Toowoomba, where two medical men can certify his sanity or otherwise.”

The outcome of the examination is not recorded, but the following month, TG Robinson & Co were offering to let the 100 acres lately used by Josiah Milstead. October saw Josiah Milstead back in command of his affairs to the extent of requesting that all persons indebted to him pay promptly or face his solicitors. Sadly, the Inn itself was put on the market at the end of 1866:

Josiah Milstead did not leave the Plough Inn. In fact, he stayed for many months longer than the new owner, a Mr CC McDonald, would have liked. Josiah considered it his place of residence, and it was not until an authority to remove him was obtained by agents JH Wilson & Co that he could be taken to Court. Even then, despite evidence of the authority, and of Milstead’s occasionally destructive behaviour, the magistrates refused to remove him. There was no evidence, they said, that he was there for an illegal purpose.

The books of the Dalby Watchhouse record that on 22 August 1867, the former publican was charged with being unlawfully on the premises of JH Wilson & Co, aka the Plough Inn. He had in his possession a pocketbook and sundry papers, three keys, one knife, a watch chain, one set of studs and case, and one bundle of papers. He was discharged with a caution.

On 24 August 1867, Josiah was back at the lockup, charged with using threatening language. He was ordered to find two sureties in the sum of forty pounds to keep the peace towards the hotel’s new owners for a period of five months.

It appears that Josiah kept the peace for exactly five months, because on 29 December 1867, he was placed in the lockup for protection (this was the practice at the time for people who were potentially of unsound mind.) The following day he was released, and an order was made prohibiting “Publicans and other persons” from supplying Milstead with liquor. Thus ended Josiah Milstead’s career in Dalby.

Theresa Milstead had her own skirmish with the law that year. A Mrs Josephine Range appeared at the door of William and Winifred (nee Whalin) Robertson’s house to discuss a promissory note. Mrs Range, instead of finding William or Winifred at home, encountered the redoubtable Mrs Theresa Milstead.

“Instead of asking to see Mr. Robertson, she asked for “Billy,” when Mrs. Milstead asked who she meant and slammed the door in her face. At this time Mrs. Range used language which Mrs. Milstead appeared to consider offensive, and hence resulted the assault, which complainant stated to be of a cruel nature, defendant having pulled her to the floor of the verandah by the hair of the head and jumped upon her and kicked her. It was sufficient provocation if an assault were made. Dr. Howlin was called to testify to the injuries complainant had sustained but stated that he had not been able to find a mark or a bruise, although she appeared to be greatly agitated. In cross-examination he stated that if a person of defendant’s “size and weight” were to jump on somebody, that somebody would run great risk of being hurt, and there would be marks left, most likely bones broken. Several witnesses were called, and after consideration, the Bench dismissed the case.“

After the Plough Inn.

Josiah Milstead.

Josiah Milstead, once he had been persuaded to leave the Plough Inn, moved on with his life, though in much reduced circumstances. 1868 found him shearing at Jimbour Station outside of Dalby – he was 42 years old and in reasonable physical health. Hard work on remote stations kept him away from places that sold liquor.

The Bell family, with whom the Milsteads were well acquainted in Dalby civic life, owned Jimbour. At the time Josiah started working there, the family had suffered the loss of the original station house and were yet to build the sprawling mansion that still stands today. I like to think that the Bells gave Josiah a helping hand by employing him, but that is pure speculation on my part.

In the late 1870s, Josiah worked for his son-in-law, who was the mail contractor at Dalby. Before that, he laboured about the Darling Downs shearing sheds. He was arrested and cautioned for being drunk in Drayton Street, Dalby in 1874, but mostly kept out of trouble.

In 1888, 58-year-old Josiah was admitted to the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum, “blind and infirm.” His record of admission makes sad reading:

Married, &c.: to Theresa Ann Whalin in Dalby. Wife died. No family. I came to Moreton Bay in 1849 and have been located mostly in the colony ever since. I have been settled chiefly about Roma and the Darling Downs. I had a public house for several years at Dalby. For the last five years I have been engaged as a labourer. For two years back, I have been employed by Mr Robertson, mail contractor at Dalby. I have no property, no cash, no relatives in the country.”

Josiah Milstead remained at Dunwich for the rest of his life, passing away on 28 August 1896 at the age of 66. Sadly, his passing was not mentioned in the press. He is buried in an unmarked plot at Dunwich.

Theresa Milstead.

Theresa Milstead continued to live with her daughter and son-in-law. She made a good living with her needle, being a fine seamstress. Occasionally, she would cater special events, such as the Election Grand Ball.

After a long and eventful life, Theresa Milstead died of cancer in 1885 and is buried in Dalby Monumental Cemetery. She was remembered fondly by the Queensland Figaro as one of founders of Dalby.

The Plough Inn.

The Plough Inn never operated as a hotel again, but for decades afterwards, the building was still known as Milstead’s, or the Plough Inn.

In 1868, Charles Fattorini ran a land agency business from it, and in 1870, it housed the Dalby Gymnastic Club. At one point it was thought that the building would be ideal for a hospital, but the idea stalled. In the 1870s, Mr McDonald transferred a share of the property to the Roman Catholic Church, and the building was used as the first Saint Columba’s Convent School. The Church decided to move its operations to the other side of Myall Creek in the early 20th century, and a new convent was built.

Some of the fun went out of Old Dalby when the Plough Inn closed. As early as 1873, the Brisbane Courier’s occasional correspondent was mourning the glory days:

A railroad ride to Dalby from Toowoomba is not a very exciting affair. The country is flat, and there is little or no sign of settlement, and the sheep in the paddocks seem easily scared. The township of Bowenville presented no sign of human dwelling worth noticing, nor indeed was there anything to look at until Dalby itself was reached.

The railway seems to have been of a retiring disposition, in that its terminus kept at a modest distance from the town, and the town itself is not lively. The spaces for streets are broad, and the houses are generally far apart, so a good deal of ground is taken up but not covered.

Since the line was opened the business portion of Dalby has removed from one side of Myall Creek to the other, but there did not seem to me that any remarkable trade was done. When the works on the line were going on there was not a little briskness and hotels multiplied. Now some of them have been converted into private residences, and some are deserted.

“Milstead’s,” once the glory of Dalby, where jubilant guests met to glorify Macalister and the City of the Plains; and where that Minister responded with an eloquence not yet forgotten – is left now to the cockroaches. I should say that the flatness of the site of this town must have a depressing effect, surrounded as it is by shoreless plains, which seem in their very uniformity of surface to give countenance to the idea that the face of the earth is really straight and not round.

Sources: