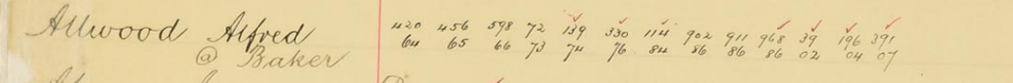

The long career of Alfred Allwood.

How did Alfred Allwood manage to spend most of his life in gaol, considering that his haul of stolen goods over 40 years amounted to less than £10, a pair of boots, a gold watch, and a cake? He wasn’t a very good thief, and on a couple of occasions entered premises and managed to steal nothing at all. He was certainly a persistent thief, and one who did not in any way learn his lesson. A heavy sentence when he was quite young seems to have sent him on a lifelong path of unrighteousness.

Alfred was born in Windsor, New South Wales, on 5 June 1848, the youngest of the six children of Stephen and Anne Allwood (nee Collins). Home life was stable for several years, until Stephen died in 1854, when Alfred was only 6 years old.

Mother Anne went to work as a general dealer, and her frequent appearances in court suggest a fiery woman with a large family to look after and a fondness for drink. The year she was widowed, she had a dispute with Mr Cooke over her son William’s apprenticeship, which resulted in Mr Cooke suffering the destruction of several windowpanes and a table. She had been ‘in liquor,’ and was fined 20 shillings.

In January 1857, nine-year-old Alfred joined a friend named John Player Box for a spot of fishing. Alfred caught a fish and got very excited and ran home to show his family. When he returned to John, he found the other boy struggling in the water. Alfred ran to get help, but John drowned. When his body was recovered, John was still holding his fishing line. (John had lost a leg several years before, and it was thought that a strong tug on the line caused him to overbalance and fall into the water.)

Six months later, Alfred’s mother died. His older siblings might have taken care of him, but Anne’s mother was still living, and it seems that he went to her (from evidence in other court cases). Losing both parents very early and witnessing the death of a friend would have scarred young Alfred, but there were no public reports of any antisocial behaviour until 1864, when he was arrested for robbery under arms.

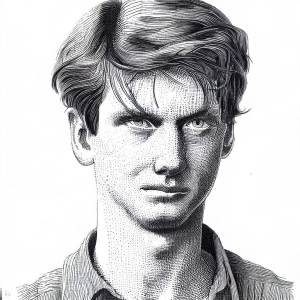

Robbery Under Arms

On the morning of 8 April 1864, Henry Symes, the Goondiwindi-Leyburn mailman, was riding back towards Goondiwindi and encountered two men walking near Bodumba. They wore blue pilot coats, had blanket rolls on their backs, and handkerchiefs tied around their hats, covering their faces. The men exchanged a “Good day” with Henry Symes, who asked the men why they had their faces covered. “To keep off mosquitoes,” was the answer.

The elder of the two men asked for directions to the creek. Symes turned in his saddle to point the way. As he did so, his horse jerked, and Symes found that the bridle was being held by the man, who also had a gun pointing at Symes. Both men, Symes realised, were pointing guns at him. The younger man had a single barrelled pistol, while the older man, who seemed to be in charge, had a six barrelled revolver.

After ordering Symes to stop, and threatening to shoot if he did not, the men demanded the contents of the mailbags. “You are great fools – what can you expect to get out of the mail?” asked Symes, as the younger man inexpertly tied his hands behind his back. “Money and cheques, I hope” was the older man’s reply.

As it turned out, there wasn’t much in the mailbags, so the men decided to take whatever Symes had on his person. “What you’ll get from me won’t fatten you,” replied Symes, as the men frisked him and found a £1 note and five-shilling order. “There is not much money there, but what there is, is all you can get, so you may as well let me go.” The younger man muttered that it was too late now. Symes offered to forget ever meeting the men and gave them his word, if they’d just go, and leave the mail alone.

The older man agreed that it was too late for that, and ordered Symes to lie in a ditch a short way off. The men took the horses and left Symes tied up where he was. Ever resourceful, the old mailman waited until the men were out of sight, and freed his hands by lying on his back and rubbing the ties against a sharp stone. He set out on foot to raise the alarm.

The robbers now had horses, but not much in the way of loot. The police offices throughout Queensland and northern NSW were on the lookout for two men – one “quite a youth,” about five feet four inches in height, fair hair and complexion. The older man was described as of similar height, “upward of forty years, with a most repulsive looking countenance.”

The youth, Alfred Allwood, clearly an incautious sort of chap, decided to go and visit his old employer Mr Cross at Warialda. He told the aghast man about the lark he had been involved in – a stickup that had only netted him twenty-five shillings. Imagine.

Mr Cross informed the police, and acted as a guide for their search, which resulted in the apprehension of Henry Irwin alias Murray and Alfred Allwood. Murray cursed Allwood for going to visit his friends when he was supposed to be on the run. The men were returned to Queensland, where they were fully identified by Henry Symes, who was in the process of a joyous reunion with his horses, saddle, and bridle.

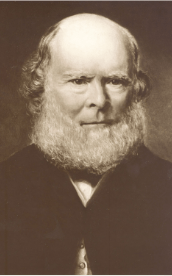

The jury, “without hesitation” found both prisoners guilty of mail robbery under arms, and Judge Lutwyche proceeded to make examples of the two prisoners. They were the first to be convicted of mail robbery in the colony of Queensland, and His Honour was anxious that the bushranging scourge in New South Wales would not occur here. (At that time, Ben Hall, John Gilbert and John Dunn were still alive and robbing their way across the sister colony.)

Henry Irwin alias Murray was given ten years’ hard labour. Alfred Allwood, who the judge felt had been led astray by the older criminal, and who didn’t seem to understand the strife he was in, was given seven years’ hard labour.

Irwin and Allwood were sent to Brisbane Gaol at Petrie Terrace. The seriousness of Alfred’s situation must have weighed on his mind – he began to exhibit signs of mental illness serious enough to cause his admission to the discreetly named Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum in August 1865.

The admitting doctor was not as concerned as the gaol doctor had been. Allwood was assessed as “very quiet and easily managed – presents no appearance of mental disease – probably feigning with the hope of escape.” Which is what, after three months of treatment, Alfred did. He headed back to his old stomping ground of Leyburn, possibly with the idea of going back to northern New South Wales. While in Leyburn, he managed to get arrested under the name of James Baker for causing a disturbance in the streets and using profane language.

Guilty of being himself.

James Baker pleaded guilty and was fined £2 for disturbing the peace of Leyburn. Barker was then remanded on suspicion of being Alfred Allwood, an escaped lunatic – one of the constables had recognised him. Allwood knew the game was up and pleaded guilty to being himself. He was sent back to Woogaroo. The doctor in charge was advised that when Alfred was picked up in Leyburn, he had been in possession of a bullet-mould, first-class revolver, and some crepe. It was clear that the patient had escaped to resume his criminal career, and he was promptly returned to Brisbane Gaol.

Early on Sunday 14 October 1866, the turnkeys at Brisbane prison were making their morning rounds when they discovered a clothed dummy in the bunk that was supposed to contain young Alfred Allwood. No trace of the prisoner was found on the premises, and his fellow-prisoners knew nothing at all, Sir, about his activities. Gone, Sir? Who would have thought it?

The following day, residents of nearby Kelvin Grove noticed some of their clothes missing from their washing lines, and food had vanished from their larders. Mr Rogers, a clerk in the Treasury, found himself lacking his horse, saddle and bridle.

Local police had reason to suspect that the suburban thefts might not be unrelated to the prison escapee. Sergeant McCarthy and a mounted policeman, set out after Allwood. Paved roads were not a feature of the Brisbane cityscape at the time, and they found a likely trail, heading west. Also, it didn’t take a genius to infer that Allwood would take off to the southern Downs, where he still had friends and associates.

Five days and 250 miles later, they had their man, who was stopping at “The Old House at Home,” near Leyburn. The fugitive was astonished to have been tracked down, and was quickly secured and returned to Brisbane gaol. He got another 12 months for escaping, meaning that he had no chance of being a free man until 1872. Allwood had been under lighter restraint than other prisoners because the gaol administrators were convinced that he may still have a mental illness. He was denied that indulgence, and sent to the newly opened penal establishment at St Helena Island to serve out his time.

The new St Helena Island prison.

During his stay at St Helena, Alfred Allwood used his time for quiet reflection and rehabilitation.

- 1868: Disorderly conduct and disobedience of orders: given 14 days’ shot drill.

- 1869: Refusing to work: given 48 hours’ solitary confinement.

- 1869: Refusing to work: given 2 days solitary confinement.

- 1870: Insolence and singing in his cell: given one dozen lashes (on the breach).

- 1870: Fighting: given 3 days solitary confinement.

- 1870: Disobedience of orders: given 4 days solitary confinement.

- 1871: Insolence: indulgences stopped and to be placed in solitary cell at night.

- 1872: Disobedience of orders, insolence, and abusive language: given 7 days solitary.

- 1872: Concealing pipe, flint steel and tinder: given 7 days solitary.

- 1872: Smoking in the yard: 7 days tobacco stopped.

- 1872: Disobedience of orders and insolence: 3 days solitary and indulgences stopped during remainder of imprisonment.

Alfred managed to resist the temptation to join Edward Hartigan in blade-wielding yard brawls, or the Wild Scotchman in his escape attempts, and never committed any violence upon the turnkeys. It didn’t reduce his sentence, though.

1872-1874: Freedom, for a while.

Alfred left St Helena on 17 July 1872, when his sentence expired. Three months later, he was reported to be one of a group of young would-be robbers who had been prowling around Warwick. “One of them, whose name is Alfred Allwood, is evidently a man of some ability and great ambition. He was a mail robber, though not a successful one, and will, should he live long enough, probably soon distinguish himself in that particular branch of the profession which he is now cultivating.” Allwood and chums left the Warwick area, and he didn’t get into any bother until the following year, when he was accused of stealing gold, silver and cheques from Mr Grigg at Roma. When the matter came to trial, Allwood claimed that he had been trying to live an honest life under the name of James Baker and pointed out the gaps in the chain of evidence. For once, a jury believed him, and he was acquitted.

In 1874, George Frazer, keeper of the Royal Hotel at St George, found himself no longer in possession of his gold watch and chain. Sergeant Cranny had his suspicions as to the identity of the new owner of the gold watch, and interviewed Alfred Allwood, whose sock drawer was found to contain the missing item. In June 1874, Alfred Allwood was sentenced to two years’ hard labour in gaol.

Back at St Helena Island, Alfred was quite well-behaved. He only offended once – being insolent and disrespectful to the Medical Officer on 30 November 1875. His indulgences were stopped for 14 days.

An incorrigible.

Shortly after Allwood returned to the mainland in June 1876, Mr Deazley, a draper who lived behind his store in Mary Street, heard someone creeping about his verandah. He lost no time in securing the stranger and calling for the police. The constables arrived, to find a man of slight build who called himself John Ball, being held down in the mud by Mr Deazley and his ward. They had a spot of bother getting Mr Ball to the lock-up, because he was able to slip his hands out of his cuffs and try and make a run for it.

Once secured, Mr Ball was recognised as Mr Allwood. Alfred had no stolen goods or housebreaking implements in his possession, but his intention to commit an indictable offence was clearly inferred by his presence where he shouldn’t have been.

In September 1876, Judge Lutwyche gazed down from the bench in exasperation. He had sentenced the teenaged Alfred Allwood in 1864, when the youth tried his hand at bushranging. Since then, Alfred had escaped from a lunatic asylum, escaped from a prison, and served another two years for having Mr Frazer’s gold watch in his sock.

Judge Lutwyche decided that the man was incorrigible, and ordered him to serve the longest sentence he could impose for the offence – seven years. Brisbane Gaol tolerated his presence for three years before prison officials decided to send Allwood back to St Helena Island.

On 15 January 1883, Alfred was again at liberty, and the Brisbane offices of the Singer Sewing Machine Company suffered a break-in. The following day, Detective Nethercote decided to arrest Alfred Allwood and William Boardman. To Inspector Nethercote’s horror, Allwood’s alibi checked out, and he was released without charge.

Alfred Allwood headed to the Western Downs, where, as John Allwood, he fell foul of the law at Roma in February 1884, receiving another three years for larceny of a cheque.

In September 1886, the newly freed Alfred Allwood shared a room in a boarding-house with a gent named Sophus Pederson, who got rather drunk and went to bed, leaving his pocketbook where it could be nicked. Which of course it was. Alfred Allwood didn’t get far, being caught red-handed in the back yard. He was, he claimed, holding it for safe keeping because Pederson was drunk. Another three years was added to his slate.

1893: The Northern Goldfields.

Freed in 1893 Alfred he decided to turn over a new leaf, forsaking his old haunts on the Southern Downs for the opportunities presented by the Northern Goldfields. This led to six months for larceny at Charters Towers in 1893, then another six months in 1895 for being illegally on premises at Normanton. The bench of magistrates in Croydon in 1896 did not appreciate his use of St Helena language in the streets of their town, and gave him three months.

Alfred Allwood was approaching fifty and had spent nearly twenty-five years in prison. Labouring work was all he could get, and he kept his head down for a couple of years, jobbing around North Queensland.

In 1901, Mr J Tyson of Townsville returned to his house one June evening, to find a light burning inside. Curious. Inside he located one Alfred Baker alias Williams alias Allwood, who had a sugar bag with some cakes in it, and a couple of household items in his pockets. Allwood pleaded guilty at the Northern District Circuit Court and was sentenced to three years’ hard labour at Stewart Creek prison. The authorities sent him on to St Helena immediately – a journey of 1,352 km or 690 miles, at the expense of the taxpayers of the new State of Queensland.

In 1904, Allwood was briefly free again, and celebrated by committing robbery with violence at Rockhampton. Another three years by the bay followed. He was released a little early this time – 1906 – which gave him a little time to spend at the Mount Morgan diggings.

In 1907, at Mount Morgan, Alfred Allwood was arrested, tried, and sentenced to seven years’ hard labour for committing a sexual act with another man. Hoping to avoid detection, the two men had sex under a bridge, and an already suspicious local the policeman followed them and caught them out. The Truth had a lot of fun with it, giving it three sub-headings: “Goldfield Ghouls. Mount Morgan’s Multy Morals. A Pair of Prurient Old Persons.”

End of his days at Moreton Bay.

Alfred Allwood, aged 59, went back to St Helena prison, served his time, and was released just as the First World War was breaking out. He appears not to have committed any further offences in his last years, before being admitted to Dunwich Benevolent Asylum, Moreton Bay, in 1921. He lingered on there for eleven years, before dying there, intestate, aged 84 on 22 June 1932.