Part 1 – Edward Hartigan’s Early Years.

In the years between Separation (1859) and Federation (1901), Queensland had its share of storied criminals. Some terrorised the roads for a few years but were captured and imprisoned– the Wild Scotchman was probably the most celebrated. There were infamous murderers who went to gaol or the gallows in various states of repentance. There were a few recidivists who spent their lives in and out of harsh penal establishments, such as Alfred Allwood.

One man was a combination of all the above. In the 1860s, he was the horse-stealing outlaw. In the 1890s, a back-roads murder haunted him. He spent nearly forty years in and out of courts and prisons.

Edward Hartigan (c. 1838 -1908) was known by many aliases – Henry Parker, George Parker, Walter Cahill, Thomas Cliffe, Edward McIntyre, Keane, Kane, Kain, and, most famously “The Snob.”

The nickname, together with a criminal history composed largely of fraud offences, conjures up an image of a gentleman thief or confidence trickster. In 1952, he was described by an overly imaginative writer as a smooth criminal – a dandy who wore spats, a bell-topper, and carried a cane as he charmed the pocket-watches out of innocent Rockhampton magistrates. (It would have been difficult to nick all those horses and conduct wild escapes from the law in a bell-topper and monocle. Not to mention a cane. The man would have been laughed off the road.)

In 1903, a journalist with an interest in criminology decided that Hartigan was a victim of a terrible compulsion. His obsession was imitating signatures and he possessed “nothing short of a mania for exercising his peculiar power.”

In reality, Hartigan was called The Snob because his trade was boot-making. Not that he spent much time at it. He was never convicted of any bush ranging offences – only forgery and uttering small cheques and orders. He was a compact, muscular Irishman who, like Alfred Allwood, received unusually harsh sentences for his early crimes and couldn’t or wouldn’t rehabilitate afterwards. And it is extremely doubtful that this man ever wore spats or a monocle.

Ireland to New South Wales

Edward Hartigan was born in Limerick, Ireland, to Michael and Ann Hartigan. Hartigan’s birth year was most likely around 1838-1840, but he gave different ages at different times to different authorities. He arrived in Australia aboard the Peter Maxwell with his parents and brother in January 1858. He was probably about 20.

A month after arriving in New South Wales, Edward Hartigan was charged with using obscene language in public at Brickfield Hill, Sydney. At the time, Brickfield Hill had yet to undergo full gentrification, and Hartigan was probably just trying to fit in.

In 1860, Hartigan was in Maitland, and was involved in a truly bizarre dispute with the wife of a publican. A Mr McDonald had taken over a pub previously licensed by Messrs Beirnes and Dillon.

One afternoon in November 1860, Mrs Catherine McDonald was at her husband’s pub, “jawing” her children, when Hartigan, Beirnes and Dillon entered the bar. Hartigan told Mrs McDonald that he had authority from Sergeant Gordon to arrest her for beating her children, and picked her up and carried her out of her house.

Catherine’s daughter Ellen had asked Beirnes and Dillon in to stop her mother’s beatings, and Hartigan was the muscle they brought along. He carried Catherine McDonald about 25 yards and set her down unharmed, then returned to the pub and his mates.

The majority of the Bench came to the view that Mr Hartigan should not have hauled Mrs McDonald out of doors against her will, however poorly she treated her daughters. He was fined £5 or in default, one month’s imprisonment. Hartigan took the month.

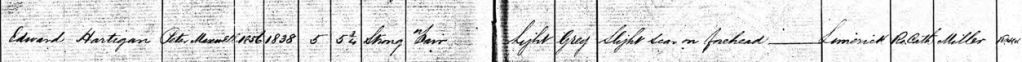

Edward Hartigan in Maitland Gaol, 1860.

Queensland

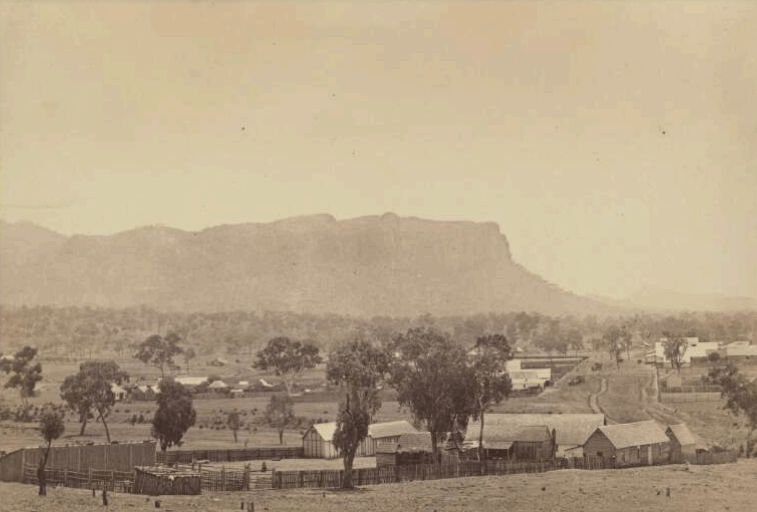

Edward Hartigan moved to Queensland in 1860 per the Eagle, shortly after his liberation. For a time, worked as a bootmaker for Patrick O’Reilly at Rockhampton.

Hartigan came to the attention of the Rockhampton police in January 1862 for fighting in the public streets, for which he was fined 20 shillings. Again, probably just trying to fit in.

The following month, he was charged with a more serious offence – being illegally on premises of an Alderman McElligott. The complainant failed to show up to court to prosecute the charge, and Hartigan was a very lucky, free man.

The opening of the Rockhampton Assizes – April 1863.

In April 1863, Edward Hartigan had the honour of opening the first ever sittings of the Assize Court at Rockhampton. Unfortunately, not as one of the dignitaries who gave flowery speeches to mark the occasion, but as the first defendant tried there.

Hartigan had been knocking about at Bowen, frequently drunk, as had another man, Peter Bolger. Bolger had a purse full of cheques, and found it empty after staying in the same pub as Hartigan. Hartigan bought himself some boots with a nice fat cheque, and had his collar felt by the authorities.

He was found guilty of the larceny of three cheques, despite a very canny defence by Mr Lilley. “Nothing being known of the prisoner; the Chief Justice ordered him to be imprisoned and kept to hard labour for four calendar months.” He wouldn’t be unknown for long.

Hartigan served his four months at Brisbane Gaol, and was discharged on 6 August 1863. His conduct while in their custody had been “orderly.” He celebrated his release by getting very drunk and was arrested and fined 5 shillings.

Disputed Property in Frog’s Hollow. Brisbane 1863.

In September 1863, Edward Hartigan took to visiting the houses of ill-fame in Frog’s Hollow. After one such foray, he charged Ellen Vickers with stealing money and property from him. After the first mention was adjourned, Hartigan and some new mates went off to drink at the very same brothel with Mary Ann Williams. It seems that Hartigan had the idea of retrieving his stolen goods. There was a scuffle, and Miss Williams charged Hartigan with stealing.

Ellen Vickers was discharged on the count of stealing from Edward Hartigan, who was tried at the Brisbane Supreme Court and found not guilty of stealing from Mary Ann Williams. It was a popular verdict – one suspects that Misses Vickers and Williams had deprived a few of their clients of a few of their sovereigns, and this was seen as a victory for the customers.

“The verdict was received with some manifestations of applause, which, however, were promptly checked.”

The Courier.

Around the same time as Hartigan’s visit to the home of Williams and Vickers, he was suspected of having stolen a watch and chain from a roommate at a South Brisbane boarding house. Another man had been arrested – a person from whom Hartigan said he had bought the watch. Defending himself in Court, he managed to throw doubt on the prosecution’s witnesses. He was found not guilty and walked free from the dock, only to be arrested on another charge before he could reach the outside world.

This time, he was accused of larceny at Ipswich, in company with Michael Healy. February 1864 found Hartigan, on remand at Ipswich, beguiling the hours by whittling away at the mortar around a brick near the woodwork of the cell door. He had very nearly made a hole big enough to squeeze through when the turnkey made his rounds and caught him. He was forced to spend his remand time at Brisbane Gaol, where his behaviour was now noted as “disorderly.” The Attorney-General withdrew the charges against him, and he was discharged on April 28, 1864.

Now a notorious horse thief, and briefly tied to a tree.

“Oh, it’s no use, my fine fellow, you are in the hands of Victorians now!”

One of Mr Hughan’s men.

Between 28 April 1864 to 12 August 1865, nothing further was heard of Edward Hartigan, at least as far as the world outside Springsure was concerned. Then he suddenly turned up in the pages of the Rockhampton Bulletin and other publications as a fully-fledged desperado on the run. It turned out that he had been quietly building a reputation in the Capricornia region.

In early 1865, a man who called himself Kane or the “Snob” was sought by the police at Springsure for obtaining goods and money under false pretences. In April, Kane was tracked down to the Planet Inn at Brown River, where a drunken mate named Thomas Macnamara prevented Constable Crogan from apprehending him. Macnamara got three months for his pains.

Kane was subsequently arrested and identified as Edward Hartigan. In May was committed for trial for the assault on Constable Crogan as well as two charges of horse-stealing. Confined in the cells at Springsure, and reluctant to be tried at Rockhampton again, he escaped from the lockup and went bush.

On 12 August, the Rockhampton Bulletin published a missive from one Allen Hughan, describing in florid, boastful detail, his capture of the Snob at Gordon Downs. His cook had alerted him to the identity of a stranger in the camp, and a daring capture was made by his men. After tying the outlaw to a tree, Hughan claims to have delivered his prisoner a stern lecture on the lamentable moral condition of the outlaw kind.

Unfortunately, no sooner had Mr Hughan sent one of his men to town to alert the police, and more importantly, send the letter, than he found himself missing a prisoner. No tree could hold Hartigan.

Edward Hartigan was properly recaptured in October and was very securely manacled henceforth. He was brought to Rockhampton to face charges of escaping from lawful custody, assault and horse stealing at the January 1866 Assizes. The press speculated on the length of the term the rogue would get. After months of remands in 1866, during which the prosecution failed to arrange its witnesses, all charges were dropped – even the escape from the Springsure cells. Hartigan was free.

Hartigan tried to keep a low profile after the nearly year-long legal saga he had been involved in. In February 1867, he ventured into Rockhampton, and was promptly arrested by Sergeant Doyle. “There would have been no bloody fear of me coming into town if I thought the coast was not clear,” remarked Hartigan. He was charged with forging a cheque.

Once again, Hartigan was committed to take his trial at Rockhampton. This time it would be the Assizes in March 1867, where, once again, the Crown offered no evidence. Discharging the prisoner, the judge urged Hartigan to reform and find an honest living. As soon as Hartigan left the dock, he was seized and arrested on a new charge by the constables.

Hartigan was charged the following day with uttering a forged cheque to a Mr Allen, publican on the Clermont Road. He was remanded to the May 1867 sittings, where it was revealed that Mr Allen, although served with subpoenas, had not attended to prosecute the matter. Once again, the Bench warned Hartigan to consider a more righteous way of life, and released him from custody.

Hartigan could be forgiven for feeling bullet-proof. Since his conviction in April 1863, no charge against him had been successful. He had no interest in taking the honest way in life and returned to Clermont, where he received a shepherd’s wage cheque for £2 in change at a store and tried to tender it in an altered form for £12. He was told the cheque in that form was no good, and he got out of town fast. Police tracked him to the Taroom area, and he was brought to Springsure, then Clermont to be locked up again.

In September 1867, he was duly charged with forging, uttering and horse stealing (the getaway). He informed the magistrates that he was quite used to coming before police courts, thank you very much, and was sent to Rockhampton again, for his trial.

Taking Hartigan and a co-accused named Thomas Francis from Clermont to Rockhampton involved an armed police escort of two officers on horseback. It was quite a distance, and Sergeant Delane and Constable Laing and the prisoners had to camp overnight at Mackenzie Scrub, where Hartigan managed to get out of his handcuffs and leg irons and escape. (Presumably, the armed police officers were asleep at the time.) Francis, not being as nimble, remained in Delane’s custody.

A contingent of Native Police lost Hartigan’s trail, but Constable Laing redeemed himself by locating Hartigan two days later at a miner’s camp after hearing the man’s distinctive Irish voice. Laing called on Hartigan to surrender, and when he refused, fired his weapon above the fugitive’s head. Hartigan surrendered.

The trial he lost.

On 3 December 1867, Edward Hartigan, together with Thomas Francis, faced trial at Rockhampton. Francis entered a plea of guilty, Hartigan pleaded not guilty. Despite one witness having died in the time it took to bring the case to trial, there was enough evidence for the jury to find Hartigan guilty of uttering – the Crown Prosecutor withdrew the other two charges. The judge gave the Snob ten years, and he gave the judge an almighty spray, and had to be restrained by several police officers.

He was told that he was going to serve his time at the overcrowded Brisbane Gaol. The authorities in Brisbane had come up with a solution to that overcrowding – repurposing an old quarantine station on an island in Moreton Bay. It was to be called the St Helena Penal Establishment.

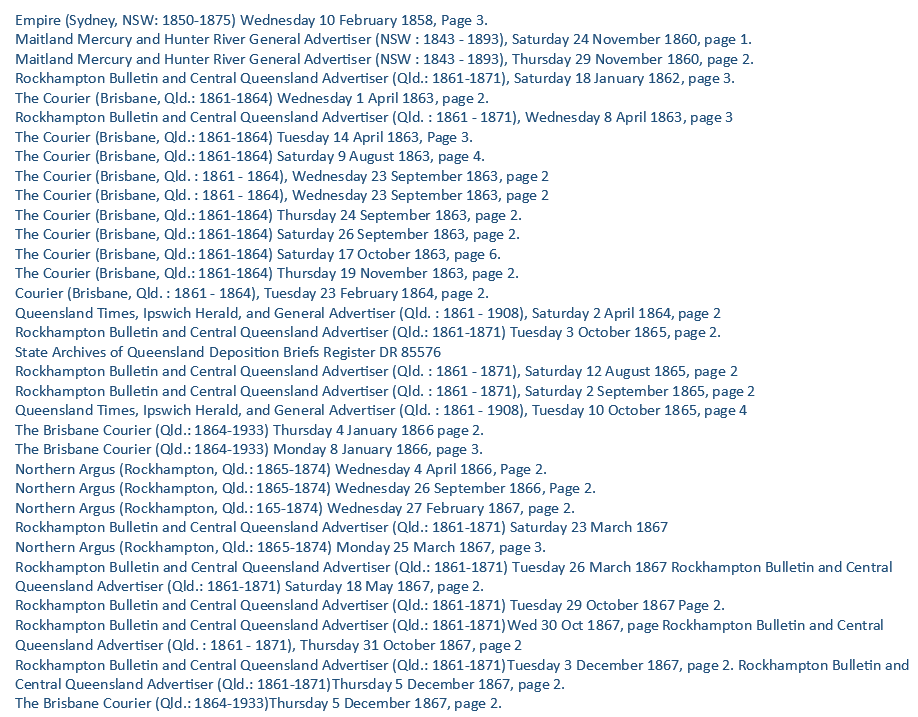

Citations:

NSW, Australia, Gaol Description and Entry Books, Maitland, 1860.

Photographs from the digital collections of the State Library of Queensland and the National Library of Australia (all images out of copyright).

Photographic records, descriptions and criminal histories of male and female prisoners – HM Gaol Brisbane 01.05.1875-12.06.1876. ITM 654069. State Archives of Queensland.

1 Comment