St Helena Island

Hartigan arrived at Brisbane Gaol on 13 December 1867. The Brisbane Gaol authorities recorded him as 5 feet 5 ½ inches in height, of slender build, with a ruddy complexion, sandy hair and blue eyes. He could read and write, was unmarried, had no children and belonged to the Church of England.

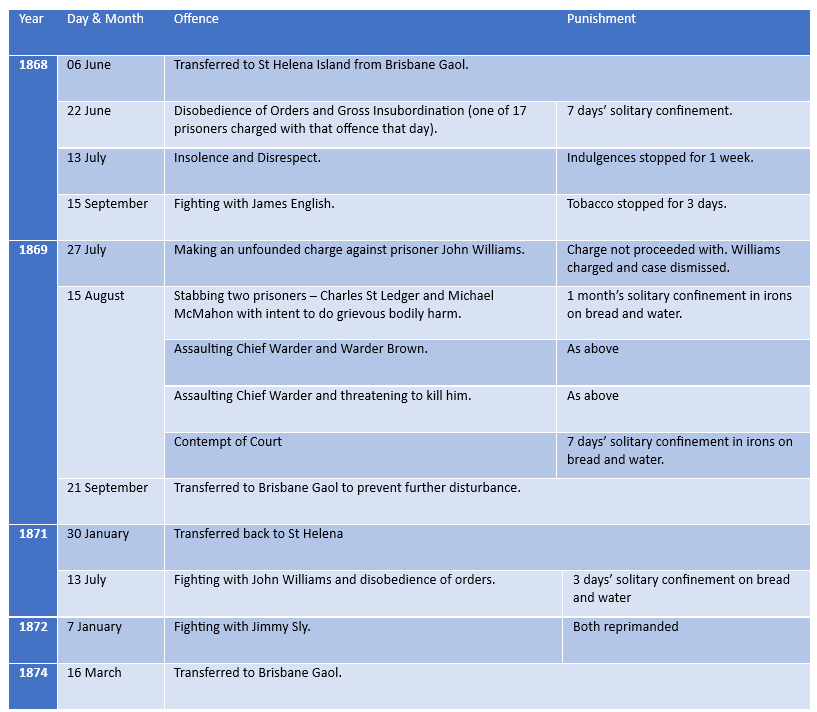

Hartigan spent six months in the gaol at Petrie Terrace, where he was observed to be “orderly.” On June 5, he was discharged to St Helena Island Penal Establishment, which had been open less than 12 months.

If I wished evil to anyone, which I do not, I would pray that he might be left in the scrub at St. Helena for twenty-four hours. At the end of that period, he would, by the influence of mosquitos, be rendered a deserving applicant for treatment at Woogaroo.

The Brisbane Courier, 1867.

Prison Life at St Helena

He proved to be quite a different man in gaol to what he was when at liberty. He was obedient and well conducted, and as the new system for a remission of two months in every 12 came into vogue in 1868, the Snob must have determined to do all in his power to merit all the remissions possible. His behaviour was so commendable that in 1875 he was again a free man.

The Rockhampton Bulletin, 1924.

One of the many legends surrounding Edward Hartigan is that he was able to put on a façade of good conduct whilst in custody, earning remissions on his sentences. Let’s see how he settled into island prison life:

If the boy doesn’t report you, I will.

The main cause of Edward Hartigan’s trouble at St Helena occurred in the very early hours of 11 July 1869. Hartigan was sharing a cell with a young man named John Burns and John Williams alias “Quinn.”

John Burns was a teenager who’d been convicted of horse stealing for a second time at the same sittings as Hartigan. To the judge, he “appeared to be possessed of a very slight amount of intelligence,” having never been to school. He was slightly built, blond and blue-eyed. John Williams alias Quinn was a short, stout, baker from Adelaide. At 31, he was a year or two older than Hartigan, and had been convicted at Maryborough of larceny and sentenced to eighteen months.

The evidence of the guards on duty that at St Helena that night was that they knew nothing had been going on until John Williams tapped at his cell door, and said he wanted to report Hartigan for attempting sodomy on Burns.

Hartigan and Burns, as well as eight other prisoners, recollected the night differently. All heard Edward Hartigan remark to Williams “Go away from that boy’s bed, you’ve no business there. If the boy doesn’t report you, I will.” Williams responded with some profanities, and said he would make the first report.

Burns made a complaint against Williams to chief warder Hamilton the following morning, as did Hartigan. Despite this, Hartigan was charged by the Chief Warden with making a false complaint against Williams, and was tried before the Visiting Justice.

After hearing the evidence of prisoners Frederick Goodfellow, Charles Pritchard, Thomas Carey (Tom the Devil) and Burns himself, the Visiting Justice abandoned the charge against Hartigan, and charged Williams with attempting to commit an unnatural offence.

In this trial, evidence was given by Burns, Hartigan, Daniel Rae, Edward Cooper, Alfred Allwood and Frederick Rogers. Hartigan claimed to have overheard Daniel Rae saying to Williams – “By Christ, I should have the first report if I were in your place.” Alfred Allwood remembered Williams saying to Hartigan “I’ve caught you to rights now.” In his evidence, John Burns denied that Hartigan had ever attempted any intimacy with him. The charge of attempted sodomy against Williams was dismissed.

There were now two camps at St Helena – those who supported John Williams, and those who believed Edward Hartigan. A few weeks later, all hell broke loose.

A Party Row

On Sunday evening, 15 August 1869, John Devine alias Parker and George Bull alias Evans, were having a fistfight in the “A” yard. The other prisoners had gathered around, while the warders were trying to restore order from the verandah. Two men involved in the Williams trial – Goodfellow and Rae – started their own brawl. Edward Hartigan joined in, but was stopped by another prisoner, Charles St. Ledger, who told him not to hit a man from the back, but to fight fair.

Several minutes later a cry went up, “Hartigan has a knife!” St. Ledger turned around, and raised his hand to protect himself, receiving a bad cut on the back of his hand. Michael McMahon received cuts on his fingers in the act of trying to disarm Hartigan. McMahon did not think that the injuries he received were inflicted intentionally. The prisoners, not the guards, were the ones who disarmed and restrained Hartigan.

(Hartigan was a shoemaker, and the tools of his trade – a knife and hammer – were sitting in an unlocked box on the verandah, supposedly under the control of Chief Warden, or at least his delegate on duty.)

After the brawl was broken up, Hartigan was removed with considerable difficulty, and locked up. The following day there was another incident, which resulted in Hartigan being charged with assaulting and threatening Chief Warden James Hamilton, and assaulting Warder Joseph Brown.

Theophilus Parsons Pugh – newspaper editor, politician, Justice of the Peace, and publisher of Pugh’s Almanac – accompanied the Visiting Justice to St Helena to try Edward Hartigan. It was nearly two days after the incident, and Hartigan was still uncontrollable. The bench adjourned for a week, to allow Edward Hartigan to calm down. In solitary, in chains, and on bread and water.

A week later, the fastidious Pugh was ready to try the matter, and Hartigan was ready to face justice. St Ledger and McMahon gave their evidence, and then Hartigan called Frederick Goodfellow to explain what was really going on in these terms: “Owing to a case in which Hartigan was concerned which was heard a little while before, there was some ill-feeling amongst the prisoners toward Hartigan and an inclination on the part of some to do him personal harm. There was a party feeling in the yard.” Hartigan stated that he interfered in the fight “to prevent a weak man being ‘double-banked.'” When he realised it was likely to be a ‘party row’ he admitted that he went and got the knife and hammer with the full intention of using them.

“It’s you, you bugger, I want. Your days is numbered – there are two or three I’ll take the life of in this place and you’re one of them. I acted the man to you, but you did not do that to me you bugger.”

Edward Hartigan

Unlawful use of a night bucket lid.

Next came the charges of assaulting prison staff. Chief Warder James Hamilton deposed that was overseeing the evening ritual with Hartigan, who was allowed out to change his night bucket, then to submit to a search before being locked up again. Hamilton turned to inspect a lock and felt a violent blow between the shoulder blades. Warder Joseph Brown was then stunned by a heavy blow to his face. Hartigan had thumped both men hard with the lid of his night bucket – it bounced off Hamilton’s back and struck Brown across the nose.

That’s when Hartigan made his threats to the Chief Warder. In cross-examination by Hartigan, Hamilton admitted that he had given a sheet of paper to Hartigan the day before the disturbance in the yard. He denied Hartigan’s accusation that he had received a letter from Hartigan the following day.

Tellingly, Hartigan accused Hamilton of telling Williams (the prisoner against whom Hartigan had made a charge of sodomy and vice versa) to “bring the matter to a barney in the yard,” in order to provoke Hartigan. Thus “it would be no use for you (Hartigan) to bring forward any more complaints as you would not be heard.”

This might also explain Hartigan’s remark, “I acted the man to you, but you did not do that to me.” It’s likely that Hamilton would have been delighted to find a reason to suppress or remove the tempestuous Hartigan.

Hartigan pleaded guilty to the assault, but not the death threats, because “I was in such an excited state at the time that I cannot say what my intentions were.”

He was sentenced to a month in solitary confinement, in irons, on bread and water. The bench, aware of “party” tensions that Hartigan believed came from the Chief Warden, recommended that the prisoner be transferred to Brisbane Gaol “to prevent further disturbance.” Hartigan was duly removed to Petrie Terrace gaol.

In 1871, he was transferred again to St Helena. He had two fights – one with Williams, which was probably inevitable. (Williams served three short terms during Hartigan’s time at the Island.) The other was with one Jimmy Sly, which can’t have been a dangerous fight, because both men escaped with a reprimand. Hartigan was sent back to Brisbane before being released (unleashed?) on an unsuspecting colony in 1875.