More hard time.

Edward Hartigan was released from Brisbane Gaol in January 1875. According to his account, he had been quietly at war with Samuel S Priday, the Principal Turnkey, Storekeeper and Clerk at the Gaol, for some months. He had been asked to keep tabs on other prisoners in return for special treatment. Hartigan refused, wanting to keep his head down after his troubles at St Helena.

Hartigan felt that Priday was “down on him,” a suspicion confirmed when Priday visited his workplace in Brisbane and told his employer just who was working for them.

This was in contravention of Government orders that the release of prisoners should not be publicised in such a manner that it would prevent them finding honest work in the community. Hartigan claimed that he wanted to make an honest living, but couldn’t continue in Brisbane, where his presence was now well known. He went bush to work for George Logan Rankin, as a cook for his drovers.

Back to Springsure.

In late August 1875, the Rankin cattle mob arrived in Springsure, and Hartigan quit (after, he claimed, his criminal history was again discovered by workmates). He was paid out with a cheque signed by Rankin.

In the following days, Hartigan used a cheque to purchase a horse from the local hotelkeeper, and then visited the premises of Ah Sam and tendered a cheque for forty-two pounds. Ah Sam had his doubts about the cheque, causing Hartigan to offer several other cheques to the same value. While Ah Sam went to find out if the cheques had any value, Hartigan abruptly left town on his newly purchased horse.

It turned out that all the cheques were from the account of G Logan Rankin, but the signatures on them, when compared to the real signature of Rankin, were forged.

After a few frantic hours of searching, the police were able to locate sufficient horses to start a chase, giving Hartigan a good five-hour start.

The following day, Hartigan cashed one of the cheques – valued at fifteen pounds – with Mr PJ Storck, who realised he’d been handed a forgery when the police arrived to warn him about Hartigan’s presence in the district.

Undeterred by the police on his trail, Hartigan stopped at Mount Stewart, and put down a deposit on some land. Using the name Atkins, he managed to trick the chequebook straight out of the hands of a station-owner named Morgan, then set about hiring an overseer and some indigenous people to strip bark for him.

The Springsure Police followed his larcenous trail, eventually capturing him at his new premises at May Downs. He was very carefully conveyed back to Springsure, where he was remanded to take his trial at Rockhampton in December 1875.

Back to St Helena.

On 6 December 1875, Edward Hartigan faced Judge Hirst and a jury at Rockhampton, charged with forgery. The horse stealing charge was not proceeded with.

The prosecution brought out G Logan Rankin and Peter Joseph Storck to give evidence of the offences. It was, of course, damning.

The defence produced no witnesses, but Hartigan’s lawyer, Mr Melbourne, made inroads into the credibility of the police and the Springsure Police Magistrate. Part of the prosecution’s evidence was a signed statement of confession, given at Springsure during the committal hearing.

It turned out that the Springsure Magistrate, instead of taking the depositions himself, or having his clerk write them down, delegated the task to a police officer – Inspector Murray. Hartigan objected, but was told “I’ll get whom I like to write the depositions.” Mr Melbourne submitted that the confession was in Inspector Murray’s words, not Hartigan’s. Damning, but not enough to prevent the jury finding Hartigan guilty. Judge Hirst sentenced him to fifteen years’ penal servitude.

“Prisoner seemed moved by the sentence, but said, nothing, and was at once removed from the dock.”

The Rockhampton Bulletin, 1875.

Brisbane and St Helena.

The Brisbane Gaol photograph taken of Hartigan was made not long after his arrival from Rockhampton – it is dated 1875 and records his latest conviction. It shows a weather-beaten man in his thirties, looking cautiously to the side as his image is recorded. He has light brown curly hair, light blue eyes, and a large, sharp nose. One sleeve is rolled up, the other is down, and he appears to have either dirt or dried blood on that sleeve. He appears to have been roughly dealt with. One hand is just visible, and appears to be quite small, giving credibility to the stories of him slipping handcuffs off quite easily. He looks like he’s still coming to terms with the idea of being well and truly into middle age before he would be free again.

Hartigan spent nearly four years at Brisbane Gaol, before being sent to St Helena on 7 May 1879. Several faces there would have been quite familiar – the long-sentenced and recidivists, such as Alfred Allwood. Also, Chief Warder James Hamilton was still there, but from what remains in the records, they seem to have tolerated each other’s presence. Hartigan’s behaviour seems to have been reasonably good. For one year at least.

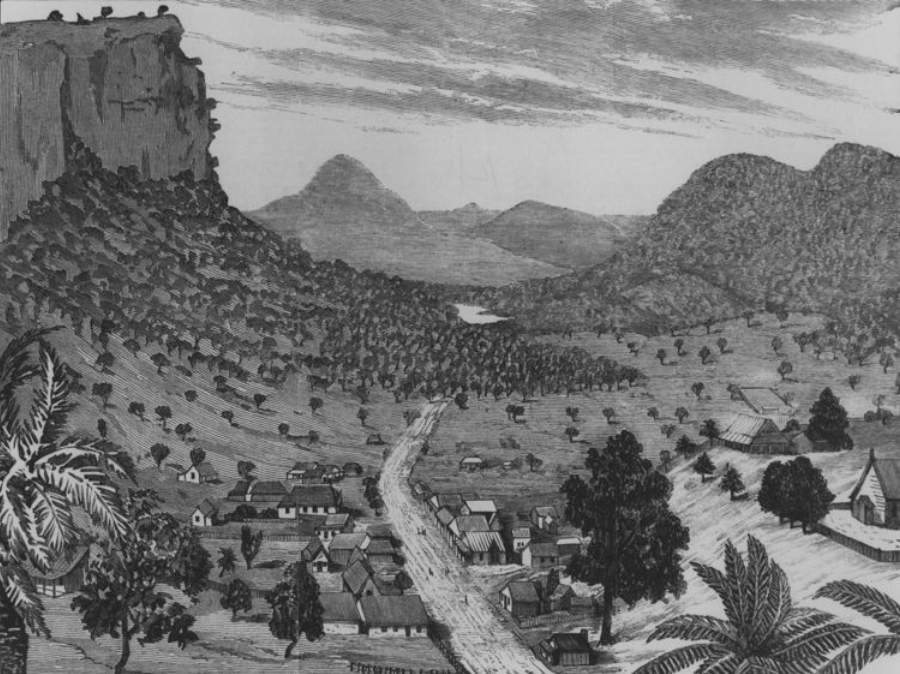

“Look up law on the subject Conspiracy.”

On June 16 1880, a telegraph was sent to Sir Ralph Gore, Visiting Justice for St Helena. It sounded ominous.

Joseph Samuel Sneyd was a Warder at St Helena Penal Establishment. His father, Samuel Sneyd, had been the Chief Constable at Brisbane, then Governor of the Brisbane Gaol until 1868. His father’s probity may have skipped a generation, or perhaps 34-year-old Joseph was a bit too gullible, but he found himself in the middle of a minor scandal with Hartigan at St Helena.

The General Correspondence Book for St Helena Penal Establishment contains the letters and depositions from this case and describes the lamplit shenanigans in real time:

Immigration Office, Brisbane 18 June 1880.

Enquiry re Warder Sneyd and prisoner Hartigan.

Sirs,

We have the honour to forward for your perusal evidence taken before us at St Helena yesterday in a charge preferred by the Superintendent of that Establishment against Warder Joseph Samuel Sneyd and a prisoner named Edward Hartigan of conspiring wrongfully to injure the trade instructor William Smyth.

We are of the opinion that the charge of conspiracy is not borne out by the evidence since prisoner Hartigan gave information to the authorities at St Helena, after which though he prosecuted the design agreed on, it was really for the purpose of convicting Sneyd of complicity and not to injure Smyth.

It is however we think shown that Warder Sneyd did employ prisoner Hartigan to draw the cheque referred to, and though the purpose to which it was intended to turn it is not stated it is not easy to see what innocent end would be served by such a proceeding.

If, however, the documents had been conveyed to Smyth’s possession he would have found a charge of trafficking with a prisoner exceedingly difficult to disprove.

We are of opinion that Sneyd has acted very badly indeed and shown himself unfit for the position of Warder. He came to Brisbane by the “Kate” last night.

We have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your obedient servants,

E D Ross, JP

St G Ralph Gore

Memorandum for the Honourable the Colonial Secretary.

I am of the opinion that the papers before me do not disclose sufficient grounds to warrant any criminal proceedings being instituted against Sneyd. Hartigan’s statement that Sneyd gave him the blank cheque is not corroborated in any way and Sneyd’s conduct after picking up the cheque when the turnkey suddenly came upon him was, I think, not that of a guilty man, but I must say that with the suspicions the turnkey had he may have lost a point in being in such a hurry. He should have watched him and seen whether or not he would report the circumstance to the superintendent. Hartigan is a criminal of no ordinary character and may have concocted the whole thing hoping by disclosing a plot to obtain some favour or remission of sentence.

R W Little, 22.6.80.

Her Majesty’s Penal Establishment, St Helena. Thursday 17 June 1880. Before Ross Colonel JP and St G Ralph Gore Visiting Justice.

Joseph Samuel Sneyd, Warder. Edward Hartigan. Conspiracy.

John McDonald states: I am superintendent of the Penal Establishment St Helena. I know Sneyd and Hartigan. Sneyd is a warder under my orders and Hartigan is a prisoner undergoing a sentence of fifteen years for forgery.

On that Sunday evening the thirteenth instant the Chief Warder Hamilton reported to me that Sneyd and Hartigan were conspiring against the trade instructor William Smith. I warned the Chief Warder to keep a strict lookout on Sneyd and prisoner Hartigan.

On Monday morning the 14th about three o’clock the Chief Warden brought prisoner Hartigan before me and Hartigan produced a blank cheque on the Bank of New South Wales.

I asked him who have him the cheque. He said that Warder Sneyd gave him the cheque while he (the warder) was on duty in No. 2 box that morning and that he Hartigan was to fill it up in favour of the trade instructor – William Smith and return it to Sneyd that evening. I produce the cheque which I recognise by a private mark I put on it. It is not in the same state now as when I put the private mark on it. After putting the private mark on the blank cheque I handed it back to prisoner Hartigan. The cheque I now produce is filled up for the sum of twenty pounds – (£20) in favour of William Smith and is signed by Edward Hartigan. It is on the form on which I put my private mark and was taken from Warder Sneyd in my presence about a quarter past six on Tuesday evening. I ordered Sneyd under arrest and to be confined to the barracks. John McDonald.

James Hamilton states: I am Chief Warder at the Penal Establishment St Helena. I know Sneyd and Hartigan. Sneyd is a warder here. Hartigan is a prisoner. On Sunday evening the thirteenth instant while trying the locks after locking up time about 55.15 I heard a rustle on the floor at the door of Hartigan’s cell, No. 32.

I looked down and saw a piece of paper moving underneath the door. I took the piece of paper. Hartigan was locked up in his cell at the time I heard the piece of paper on which was written in pencil, “I have something very particular to tell you. Call me out in the morning.” I showed the piece of paper to the Superintendent after making my usual report directly afterwards. As soon as he had read it, I destroyed it. I got the key of Hartigan’s cell from the Superintendent, returned to the gaol and opened the cell and spoke to prisoner Hartigan.

I asked him for his information. He told me that he was asked by Warder Sneyd if he got him a blank cheque would he (Hartigan) fill it up in favour of William Smyth the trade supervisor.

Hartigan said he had promised Sneyd to do so. I asked Hartigan if he had the blank cheque then. He said, “No, but I’ll get it from him tomorrow.” I then locked Hartigan up and reported the conversation to the Superintendent, who told me to keep a sharp lookout on Sneyd and Hartigan and find out if possible if Hartigan’s story had any truth in it.

On Monday the 14th when counting out the gangs at one o’clock prisoner Hartigan reported himself sick. I told him to remain in the yard if he was unfit for work. On going round at two o’clock, Hartigan complained to me of being very bad with a pain in the stomach. I brought him to the surgery to give him some chlorodyne. As soon as he was inside the surgery, he put his hand inside his shirt and took out a piece of paper which he handed to me saying, “There you can see now whether I told you the truth last night or not.” I had doubted the statements he had made to me. I opened the piece of dirty paper and found a cheque inside of which I took a hurried description at the time. It was drawn on the Bank of New South Wales the No. 4 (as figure) in manuscript dated June 14th, 1880, drawn in favour of William Smyth for the sum of twenty pounds, signed by Edward Hartigan.

The figure 4 in the number was blotted. The figures 20 in the amount were also blotted. The small “t” in the word “Twenty” is double – there are two strokes. The Superintendent was passing the surgery at the time. I called him in and handed him the cheque.

Hartigan made the same statements to the Superintendent as he did to me on Sunday night. It was decided by the Superintendent that he should keep possession of the cheque until such time as we had a favourable opportunity of seeing the prisoner give it to Sneyd.

The reason for so doing was that Sneyd had ample opportunity to communicate with the prisoner outside on the works and could get the cheque without being detected. It was Sneyd’s turn for duty in the A and C wards from six till eight. In the evening of Thursday, the fifteenth, I handed Hartigan the cheque into his cell at half past five o’clock of that evening and saw Sneyd come on duty at six o’clock. I remained in the gateway in full view of Sneyd till a quarter past six. I then walked away. I returned in less than a minute. Sneyd was walking up the passage and as near as I could judge when he was opposite Hartigan’s cell he rapped twice on the door and walked on. I withdrew for they could see me as soon as he turned and remained away about another minute.

I then came back and saw Sneyd standing under one of the lamps in the passage with a piece of paper in his hand apparently trying to read it. I walked up the passage to him and was close beside him before he saw me, he was so intent upon the paper.

I asked him what he had got. He said he did not know; it had just been thrown at him now. I told him to come up to the light till we would see what it was. We walked up to the gateway, held the paper to the light and saw it was a cheque.

Sneyd read out the body of the cheque and then said, “You had better take this.” I said, “No, you had better hand that to the Superintendent.” I brought him into this office where we are now, and he handed the cheque to the Superintendent. Exhibit A: The cheque shown to me is the one. James Hamilton.

Cross-examined by S. Sneyd: You were walking first opposite the associated wards. I gave you a paper about target practice to read under a lamp in the corridor. You did not bring me a paper which had been thrown out to you and say Hartigan had said “Mr Sneyd, give that to Mr Nairn.”

William Smyth states: I am a warder and trade instructor on the Penal Establishment St Helena. I know Sneyd, he is a warder. Hartigan, I know too as a prisoner. Hartigan does not owe me any money neither does Sneyd. I had no reason to expect a payment of twenty pounds or any other sum from either of these men on any account whatever. I know nothing whatever of the cheque I have seen. Exhibit A.

Joesph Samuel Sneyd states: I know nothing of the cheque in question beyond the fact that it was thrown out to me in the corridor I heard prisoner Hartigan’s voice say, “Give this to Mr Nairn.” I took it to Mr Hamilton and went with him to the superintendent.

Sneyd was punished by the loss of his post. Hartigan was punished by, well, remaining at St Helena.

Hartigan’s otherwise good behaviour earned him some remissions, and he was recorded as leaving St Helena in 1887. The entry in the admission books looks like 1889, which it may be – taking into account a future sentence, because, naturally, Hartigan did not go and sin no more.