Rowdyism in Rockhampton

On 12 November 1863, a scandal that had been hinted at over the dinner tables of Rockhampton broke out in the most sensational fashion. Two prominent men of the town, who also held the Commission of the Peace as Magistrates were charged with committing assault in the public streets.

At 10 in the morning, Mr Arthur Francis Wood, Magistrate, was arriving at his office in Denham Chambers, when he was accosted by a furious Albrecht Feez (pronounced ‘fates’), also a Magistrate. “You did say something about my wife,” declared Feez. “I did, and to your face, and I am willing to do so again,” replied Wood, who was rewarded with two blows across the arm from Feez’s whip. Woods parried a third blow, and Feez left hurriedly, having become separated from his hat in the heat of the moment.

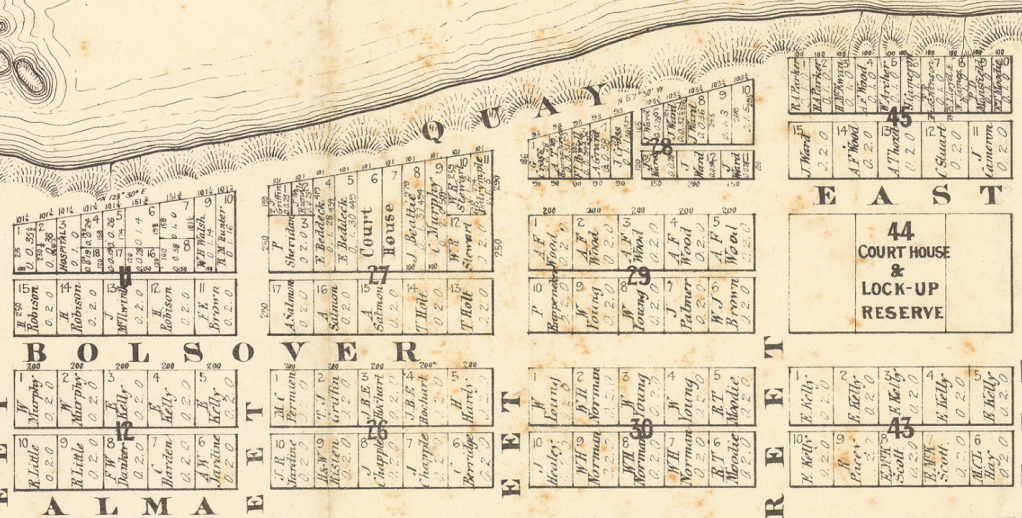

At 5 pm, Police Magistrate John Jardine was riding along Bolsover Lane near Bedek’s paddocks, minding – one presumes – his own business, when he was set upon by Magistrate George Augustus Frederick Elphinstone Dalrymple, also on horseback and wielding a whip. Mr Dalrymple laid into Mr Jardine with his whip, accusing him of prejudging a case, adding “I have the satisfaction of telling you that you are the most damnable scoundrel in Queensland.” Mr Jardine parried the blows, breaking his cane, and suffering a dented hat.

Mr Feez was summoned for assault, and Mr Dalrymple was taken into custody, and shortly afterwards was bailed by a special sitting of Magistrates.

The Courthouse was packed for the two hearings the following day, which happened to be Friday the 13th. There were an extraordinary number of Magistrates sitting that day to hear evidence against their fellow Magistrates. Seventeen of Her Majesty’s Justices of the Peace sat on the Bench: The Water Police Magistrate, WJ Brown, Esq., and Messrs. J O’Connell Bligh, FJ Byerley, Thomas Burnet, John Frazer, FR Hutchinson, RM Hunter, JA Larnach, PD Mansfield, GPM Murray, PF MacDonald, John Palmer, HT Plews, G Ranken, MS Rundle, H St George (minus his terrier, which was infamous for interrupting court proceedings), and R Scott. The only Magistrates not on the Bench were defendants and complainants.

Something was afoot, and Rockhampton was agog.

The Combatants

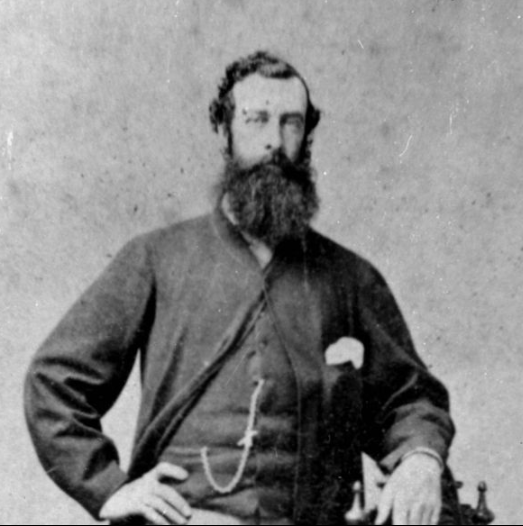

George Augustus Frederick Elphinstone Dalrymple was the tenth son of the equally exhaustingly named Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Dalrymple Horn Elphinstone of Aberdeenshire. He was born in 1826, and, in the great tradition of surplus sons, ventured to the colonies to make his fortune. He spent a decade in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) running a coffee plantation, then tried his luck in Australia. He obtained backers, and explored the North, reaching a place he named Bowen after the Colony of Queensland’s first Governor.

Dalrymple was appointed a Commissioner for Crown Lands, and a Magistrate for Port Denison. However, he preferred the dash of frontier exploration to the drudgery of clerical duties and fell out with his administrative masters. After some health problems, he took up station management near Rockhampton from 1862, but planned future expeditions.

John Jardine, like Dalrymple, was a Scot and son of a grandee. He was the fourth son of Sir Alexander Jardine of Dumfriesshire. He was nearly twenty years older than Dalrymple and had made his way to the colonies after serving with the 1st Regiment of Dragoons. In 1840, Jardine and his young family arrived in New South Wales, where he took on a run near Wellington. He suffered financial setbacks and was pleased to take up an offer to be a Commissioner of Crown Lands. Retrenched after ten years of service, he moved north to the new Colony of Queensland, being appointed Police Magistrate and Gold Commissioner at Rockhampton.

Albrecht Feez was born to, as the Capricornian put it, “a good family from one of the German or Austrian states, the writer does not remember which.” Helpful. In fact, he was born in October 1825 in Eschau, Bavaria, and served in the Army in Germany. He moved to Australia in the late 1850s, operating as a merchant first in Sydney, then Brisbane, where in October 1857 he married very well indeed. Feez’s bride was 23-year-old Sophia Milford, daughter of Justice Samuel Frederick Milford, a Supreme Court judge who had presided over the Moreton Bay circuit courts prior to Separation.

Feez became interested in the Rockhampton area following the Canoona rush of 1858 and moved his young family to Rockhampton. There he became a Magistrate, volunteer rifleman, alderman and a hugely successful trader. He was much in demand at social functions for his fine tenor voice, and whistling prowess. His wife looked after their two sons, and quietly took part in a few ladies’ social activities. Feez was a prominent agitator for separation – that is, creating a separate North Queensland state, citing a monopoly of business and political capital in Brisbane. (He was not, however, above giving a lot of business to Brisbane interests at the same time. One must be pragmatic.)

Arthur Francis Wood was born in England in 1826, and emigrated to the Colony of New South Wales, where he took up selections and worked as a surveyor. In October 1858, Wood was appointed as Government Surveyor at Rockhampton, and settled in that district, where he remained for the rest of his life. He invested in property in the area and married in 1860. He was also a Magistrate, often sharing the Bench with other Commissioners of the Peace, including Albrecht Feez, George Dalrymple and John Jardine.

The Scandal

What could have caused four respected Magistrates to become involved in public horse-whippings?

Constable Michael Buckley of the Rockhampton Police was walking home from work one evening in early October 1863, when he saw a man and a woman “committing an act of indecency” in the Courthouse Reserve.

Buckley did not arrest the pair, although he recognised the two prominent people involved. Instead, he made a verbal report of the incident to Chief Constable Foran the next morning, saying that he had “seen a case last night, which astonished me.” Chief Constable Foran would later claim that he did not think Buckley was making a formal report of a crime, and did not investigate it. That did not stop Foran mentioning the matter to (at least) two underlings.

Rumours began to circulate in Rockhampton, and Police Magistrate Jardine was asked to investigate the police handling of the matter. The person doing the requesting was one George Elphinstone Dalrymple. Dalrymple claimed that the rumours were “scandalous, malicious and utterly false,” and were “spread solely by the Police.”

On 9 November, Jardine held a closed-door partial investigation, calling in Foran and Buckley. He decided that the case wasn’t within his jurisdiction as a Magistrate and advised Dalrymple (with whom he had previously been on good terms) of his decision. Dalrymple responded that he wanted a full investigation of Chief Constable Foran and his conduct. Jardine refused. The men met on the street on 12 November 1863, several hours after Albrecht Feez had horsewhipped Arthur Wood for saying something about Mrs Feez.

The reason for Dalrymple’s keen interest, and the two assaults that occurred on 12 November 1863, was that the rumours identified the clandestine couple in the Courthouse Reserve as himself and Mrs Sophia Feez.

The Court Cases

13 November 1863

Jardine -v- Dalrymple was called on first, and the spectators were warned by Mr Dalrymple’s lawyer. “I am directed by the Bench to state that anyone who is found manifesting either applause or disapprobation in the Court, during the hearing of the case, if he can be discovered and pointed out, will be immediately committed. I hope that after this warning that all present will conduct themselves properly.” It seems that all present were unable to do so, as certain evidence presented was greeted variously with “sensation”, “suppressed merriment” and “much laughter.”

The details of the arrest and the hurriedly assembled bail hearing of the night before were deposed to, and then Police Magistrate John Jardine took the stand as the complainant.

“He rode in front of me a short distance, and stopped opposite me and said, ‘Mr Jardine, you have prejudged the case (or a case)’; I said, ‘Mr Dalrymple I shall be very glad to hear you at a proper time and place.’ He replied, ‘By God, you shall now,’ and immediately raised his whip.“

Evidence of John Jardine

Dalrymple, in between blows directed at Jardine’s head and arm, told his victim, “You are fostering a damnable scandal for the purpose of carrying out your own diabolical ends.” He also told Jardine, “I have the satisfaction of telling you that you are the most damnable scoundrel in Queensland.” (Sensation in courtroom.)

In other words, Dalrymple thought that Jardine had not done enough to prevent the spread of the gossip and had allowed Dalrymple’s name to be blackened. Dalrymple was also a great friend (and neighbour) of Albrecht Feez and his wife. In his fury, he acted in a way that drew the most attention possible to the situation.

Other witnesses were called, including an elderly Irishman named Luke Lawlor, whose evidence was greeted with raucous laughter, and who suffered the indignity of being described as “rather stupid” by the Bench, when the veracity of his evidence was challenged by Jardine. (Jardine came off as a little cowardly in Lawlor’s account.) The Bench decided that Lawlor was too simple-minded to concoct a lie.

The Bench, all seventeen of them, decided to block Jardine’s desire to explain what the “case” Dalrymple complained of was about, and chose to commit Dalrymple for trial at the next Rockhampton Assizes.

The case of Wood v Feez was heard next. Arthur Francis Wood deposed to arriving at his office to find Albrecht Feez waiting for him, a short contretemps, and Mr Feez running away without his hat. The assault – short and not injurious – was not taken as seriously as the previous case. Wood’s solicitor remarked that Feez “left his helmet on the field – I don’t know whether that’s the custom in the Prussian Army or not.” To which Feez’s lawyer replied, “And I suppose you sang “conquering hero comes.”

The Bench, hearing the matter as a summary assault case, delivered its decision: “In this case the Bench have come to the conclusion that the assault has been proved. In fact, it is not denied. We think we should be wanting in our duty if we did not inflict a substantial fine. It is a great pity, the Bench think, that gentlemen who are magistrates should break instead of preserving the peace. The Bench have therefore, decided upon inflicting a fine of £5.”

As a result of the cases, the names Dalrymple and Feez did not appear in the Commission of the Peace (list of Magistrates) for the year of 1864.

That the case was the talk of Queensland is an understatement. The Rockhampton Bulletin opined:

“A quadrilateral combat of the above description between four of Her MAJESTY’S Justices of the Peace, happily does not occur every day, and is an event not lightly to be ignored by ourselves, or passed over with indifference by others. Temporarily it will confer upon Rockhampton an unenviable notoriety; permanently it can hardly fail to result in a judicious pruning of the excrescences on this Bench.”

The Courier’s Rockhampton correspondent noted, mournfully:

“Some time ago the people of this town were accused of ‘rowdyism,’ and resented the accusation with much virulence – they would none of it – and began to fret and fume at the least word of disparagement. Any impartial critic who reads the police reports published in the local papers of last Saturday, will allow, I think, that the epithet was not misapplied, and it may well be doubted after the expose last week whether we ‘noble and high-souled’ people as we are, are fitted to govern ourselves as we wished to do.

I shall give therefore merely a broad outline and leave you to glean the details from the local prints. In the first place, then, a very serious scandal was disseminated about a certain lady and Mr. Dalrymple, late Police Magistrate at Port Denison. It is enough to say that there were dark whispers with reference to the character of the intimacy between Dalrymple and a certain lady, and that some of these hints being made rather public an investigation was called for, and conducted in private before twelve of the magistrates.

Meanwhile the slander, that at first was only spoken of in whispers, became the chief topic of conversation, and so it came about, I presume, that Mr. Wood having indiscreetly given publicity to his opinion of the lady in question, was horsewhipped in the street by her husband. That harmless castigation was the same evening followed by another of a much more serious nature.”

The Aftermath

During the Rockhampton Civil Assizes of April 1864, George Elphinstone Dalrymple was found liable for £500 damages for defaming the character of Police Magistrate John Jardine. Dalrymple was unable to attend in person, having been cut off by floods.

Dalrymple’s trial for assaulting John Jardine was set down for the Rockhampton Assizes of October 1864, but Jardine’s remote new posting prevented him from attending to prosecute the matter. Dalrymple’s charge was dismissed.

Dalrymple returned to dashing activities, opening up Cardwell, and the Valley of Lagoons. He removed himself from his business entanglements and entered politics as the first member for Kennedy in the Legislative Assembly of Queensland, and was, for a period in 1866, the Colonial Secretary.

After politics, and a bout of ill-health, Dalrymple returned to station management (unsuccessfully), and exploration, at which he succeeded, but it was costly to his health and finances. He was appointed Gold Commissioner at the Gilbert Diggings in 1871. He explored further north of Cardwell and in 1874 was appointed Government Resident at Somerset, the very establishment his old enemy Jardine had set up in the wake of the horsewhipping scandal. He arrived at Cape York, beset by ill-health and suffered a stroke. He was returned to Brisbane to recover, and then travelled to the UK where he died at St Leonard’s Sussex in January 1876.

In April 1864, Rockhampton bade farewell to Police Magistrate John Jardine, who was sent to about as distant a posting as one could imagine – Somerset in Cape York. It was a promotion, but to an incredibly remote location. Jardine travelled by sea to take up the office of Police Magistrate, while two of his young sons, Francis Lascelles (Frank) and Alexander William (Alick) travelled overland with cattle and horses. After nearly 10 months of waiting for their arrival, Jardine Snr had despaired of seeing them again, when they arrived, exhausted but exhilarated, having survived unforgiving countryside, weather, stock loss, and encounters with the indigenous people along the way. [1]

In early 1866, John Jardine returned to Rockhampton, and his old duties. He remained there until his death in February 1874. Frank Jardine remained in the Cape area, married a Samoan princess and did a lot of dashing frontier things that George Dalrymple could only have dreamed of.

Sophia Milford Feez, while not directly named as the lady at the centre of the Magisterial scandal at Rockhampton, was fairly easy to identify through reporting of the court cases -“You did say something about my wife,” and “he (Mr Feez) was the injured person in the matter.” She understandably withdrew from Rockhampton public life after November 1863, and the following years were unhappy ones. Her father, Justice Samuel Milford, passed away in Sydney in May 1865, and her brother Herman died only six months later.

In October 1866, Sophia Feez made her last will and testament. Perhaps she had received bad news from the doctor or had some idea that it was wise to get her affairs in order. She had property of her own, and made some interesting and specific bequests, leaving certain sums to female relatives on the condition that the money would always be in their name, and not to be taken ownership of by any future husband. She then travelled to Sydney, where she died on 16 January 1867, aged 32. She left two young sons, Adolph Frederick Milford Feez (who became a prominent solicitor) and Arthur Herman Milford Feez (who became a King’s Counsel).

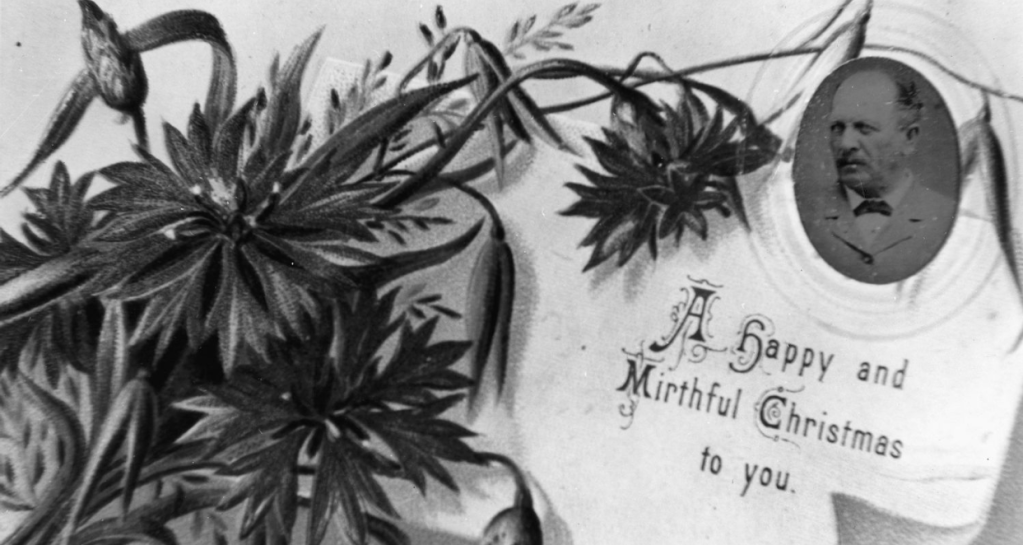

Albrecht Feez’s life after the horsewhipping scandal continued at its frantic pace. In December 1865, one of his warehouses burned down, an event which caused material loss, disgruntled workers, letters to the editors of both Rockhampton newspapers, and lawsuits. His business sense was only matched by his litigiousness. Feez continued to agitate for separation, and campaigned to be restored to the Commission of the Peace after being struck off following his conviction.

Albrecht Feez went from alderman to Mayor of Rockhampton in 1879, then served in the Queensland Legislative Assembly from 1880-1883 as member for Leichhardt. In 1885, Feez retired and moved back to Munich, travelling the world (including many trips back to Rockhampton) as a gentleman of leisure. He never remarried and died in Munich in 1905.

Lastly, the rather quiet Arthur Woods, who was on the receiving end of Feez’s fury in 1863, continued to work as a Magistrate and surveyor in Rockhampton, where he passed away after a brief illness in 1891. Apart from experiencing financial setbacks at one point, his life was stable and without any further scandal.

Citations:

Letter from Edward Farence to Sir GF Bowen, Queensland State Archives DR 112373

Clem Lack, ‘Jardine, John (1807–1874)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, (Melbourne University Press), 1972

C. G. Austin and Clem Lack, ‘Dalrymple, George Augustus (1826–1876)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, (Melbourne University Press), 1972

[1] In fact, so energetic were the young Jardines in their encounters with the indigenous people of the area, that their activities came to the attention of Downing Street.

“I regret to observe that the exploration has not been accomplished without bloodshed. I trust you will endeavour to impress upon all those who may be about to settle in any newly discovered territory under your Government the duty and the wisdom of avoiding whatever may tend to cause feelings of alienation towards us on the part of the aboriginal inhabitants.” (Letter from Edward Fardence to Sir George Bowen, 1865).

1 Comment