Rowdyism is our most prominent fault, and this prevails most while the steamers are in.

The Courier’s Rockhampton Correspondent, 1861

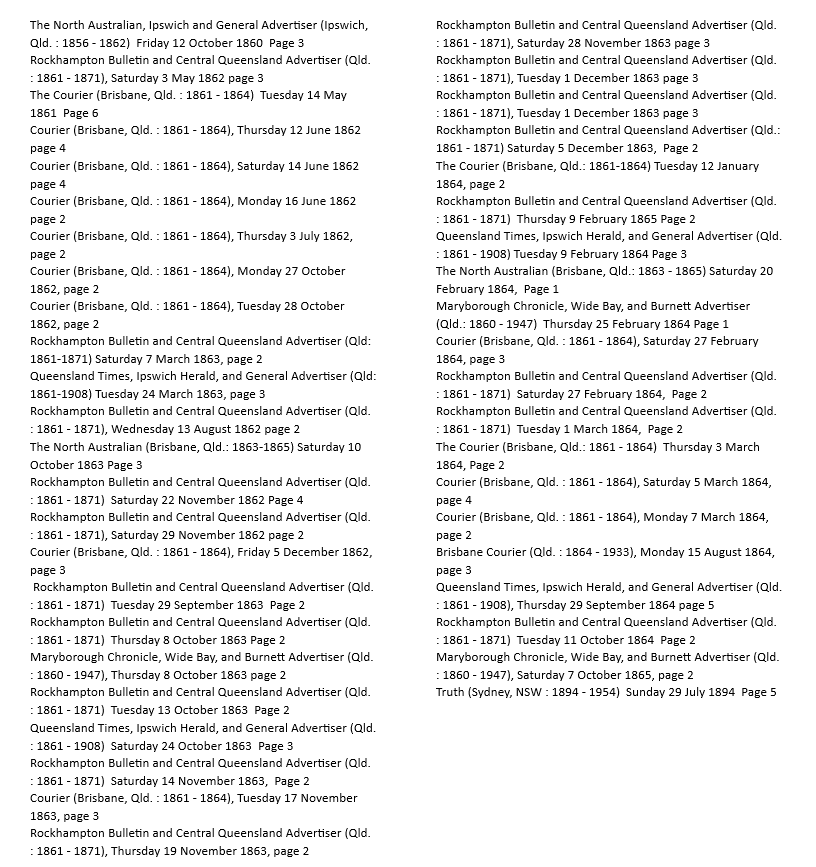

Rockhampton surged into existence rather suddenly, from a few demountable public buildings thrown together in response to a nearby gold rush in 1858, to a thriving and beautifully planned young city in the early 1860s. Brisbane could only dream of being so neatly laid out.

As Rockhampton grew, graceful public buildings were erected, wide streets were laid out, and prominent colonists purchased lots. Wealth flowed from the goldfields and the huge pastoral runs nearby, and those who had yet to make their fortunes camped cheek by jowl across the river.

Whether it was the sub-tropical climate or the prospect of sudden riches (balanced, of course, with the frequent reality of hopes dashed), people in Rockhampton were noted for “rowdyism.” Town worthies engaged in physical fights, litigated furiously and often vexatiously, and the town’s newspapers were in the thick of it.

A Founding Rowdyist

Elias Rutherford v Bigamists, Bailiffs, and his Lawyer

Elias Sedborough Rutherford was Rockhampton’s first pharmacist and was described by his friends as “a warm-hearted, if impulsive, friend.” Between 1860 and 1865, he held various public offices – Coroner, Alderman, and 2nd Lieutenant of the Volunteer Rifle Corps, and so on. He also stood trial at various times for riot, assault, hindering a bailiff and larceny.

In August 1862, Elias Rutherford was one of several men charged with “tumultuously and riotously assembling and disturbing the peace.” A group of sober, right-thinking men and women of the town had marched on the residence of the bigamous Mrs Wakefield alias Mrs McDonald, cried out their disapproval of her, and broke the front windows.[1] Fortunately, no-one was injured, and the mob grew bored and went home. Rutherford was accused of being one of the ringleaders of the mob, but there was no convincing evidence of this offered in Court, and the men were discharged. Mrs Wakefield was later charged with stealing Rutherford’s chickens, perhaps in retaliation, but was also found not guilty.

On Thursday 21 November 1863, a solicitor named Henry Boyle was sitting down to tea in his drawing room with his wife and two of her lady friends when his client Elias Rutherford appeared on his front steps and demanded to see him immediately. Mr Boyle explained that he had company, and could Mr Rutherford please wait five minutes?

No, Mr Rutherford could not. As Mr Boyle shut the door, Mr Rutherford called out violent threats then forced his way into the house and knocked Mrs Boyle aside while she was holding a baby. He turned his attention to Mr Boyle and dragged the solicitor out to the street by the throat and hair, saying, “I’ll watch for you night and day, and I’ll have your life if I drag you out of bed, and stick a knife in you.”

Mr Boyle summoned Mr Rutherford to Court and displayed the injuries on his throat causing Mr Rutherford’s new lawyer to enquire, “Is there a powerful magnifying glass in the room?”

What could have so enraged Rutherford? Mr Boyle would only answer questions from the Bench, but unconvincingly denied that it was related to a bill of costs recently delivered to his client. Albrecht Feez, local alderman, merchant and known horse-whipper, approached the witness box to give evidence, causing Rutherford (who had been trying to negotiate an out of court settlement) to instantly plead guilty.

Thus, an alderman and former Coroner was sent on his way to Brisbane Gaol for two months. His conduct there was described as “orderly.”

In 1864, Rutherford was back behind the counter of his Pharmacy, when a creditor named John O’Donnell attended the premises in company with a bailiff. A struggle ensued, and Rutherford charged O’Donnell with assault, and won. Mr O’Donnell got fourteen days’ hard labour for blacking Elias Rutherford’s eye, and a two quid fine for taking one of Rutherford’s horses away from the bailiff, who had seized them.

A month later, Elias Rutherford faced a charge of larceny of a gold ring that had been left with a local jeweller to repair. He was not indicted, because the chief prosecution witness had sailed for parts unknown.

Rutherford was still held in some esteem by his townsmen (other than Mr Boyle, presumably), because in 1865 he was nominated by a group of prominent Rockhampton gents for the seat of Archer in the colonial parliament. Whether he would have made a politician with his criminal record is unclear, but a criminal past certainly didn’t hinder the likes of William Groom from achieving high office.

Elias Rutherford died suddenly at his home on 1 October 1865, and his funeral was “attended by all the principal citizens.” He had been suffering from heart disease, and had impulsively taken an extra dose of Seidlitz powder, hastening his end.

Rowdyism on the Diggings

A young and prosperous community, is commonly the ‘Needy Villain’s Home,’ and thither flock the ‘waifs and strays’ of older cities, when probably a longer residence is ‘inconvenient.’

The North Australian, October 1863.

Mr Birmingham v Mr Reid

The prospect of sudden wealth attracted all manner of potentially rowdy folk to Rockhampton. One of the “rushes” was to the Ross Diggings in 1863. The small team who found some promising-looking veins on the Ross property shared the information with the local press, and of course, hundreds of treasure-seekers arrived at the scene. Among the throng of prospective overnight millionaires was John Peter Birmingham, who was always described, before anything else, as “a man of colour.” Once he (and to be fair, dozens of other people) discovered that there was nothing but hard work and disappointment to be found, attention turned to the original prospectors.

On the afternoon of 24 September 1863, Frederick Reid, one of discoverers of the Ross field was sitting near his tent when a group of people led by Birmingham approached him in an aggressive manner. John Birmingham said, “You bloody wretch, why don’t you tell me where the gold is.” He then pushed Reid to the ground, hit him with a bucket, and set fire to the tent. The crowd that came with Birmingham didn’t do anything to stop him, being apparently content to enjoy the spectacle of a man burning another man’s tent down.

In Court, Reid expressed hesitation in giving his evidence, having been met in the street the day prior by some other disappointed prospectors who advised him to be lenient to Birmingham. Or else.

The police had originally charged Birmingham with assault and malicious destruction of a tent. However, as a warning against rowdyism, particularly on the goldfields, these charges were substituted with one under the Riot Act – “having, in company with more than three other persons, assembled in a riotous manner, against the peace of Her Majesty, and to the peril of the lives of her subjects.” That charge attracted serious gaol time, and a few years previously would have resulted in transportation.

Birmingham was committed to stand trial on this charge, but at the last minute the Attorney-General declined to prosecute. This development disappointed W H Buzzacott, the editor of the Rockhampton Bulletin, who had been a fascinated spectator at the affray. Talk about ruining a good story.

The Circuit Court Experiences Rowdyism

Magistrate Howard St George’s Dog v Mr Justice Lutwyche

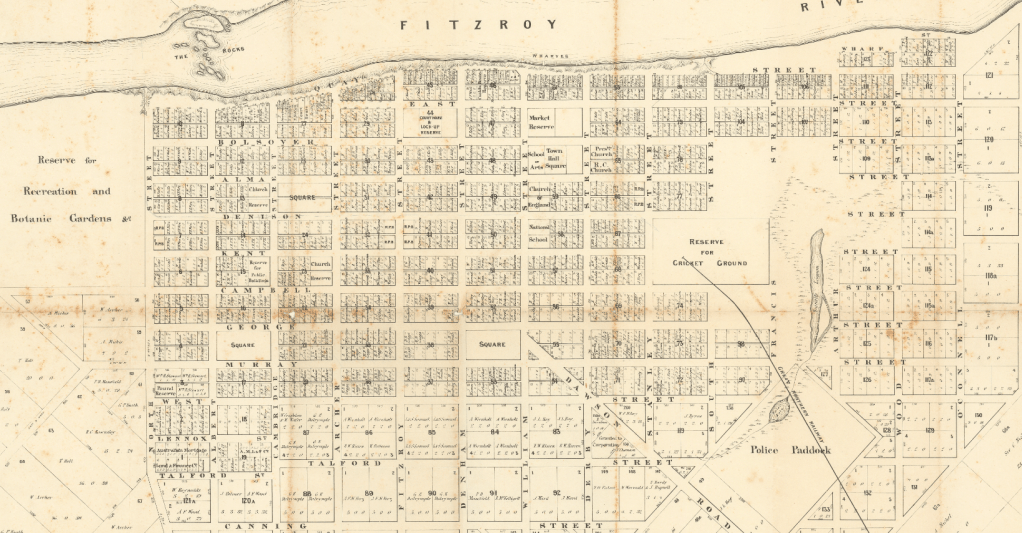

1863 was a banner year for Rockhampton. The first ever criminal sittings of the Assize Court had taken place in April, featuring the Snob as the first criminal to be tried in that jurisdiction. The second sittings were held in October, with Mr Justice Lutwyche taking the Bench in great dignity to hear a string of larceny cases.

During the trial of one Charles Ding (larceny, of course), a small terrier gained admittance to the courtroom, and ran excitedly about the room, barking and yapping with glee. Justice Lutwyche directed an officer of the Court to drive the dog outside, but “this was not however done.” Presumably, the Court officer looked at his duty statement, and didn’t see “dog catcher” listed as one of his responsibilities.

The dog persisted on its merry way, and Mr Justice Lutwyche rather understandably lost it. He ordered the animal to be caught, and its owner brought before him immediately.

It was Chief Constable Foran’s unhappy duty to do so, and to identify the owner as Mr Howard St George, Esquire, a Magistrate of the territory. The Attorney-General, Ratcliffe Pring, who was prosecuting Mr Ding, remarked that “it would be far better if Mr St George attended on the Bench than allowing his dogs to be running about the Court, interrupting the business. He thought the Dog Act required enforcing in the town.”

Mr Justice Lutwyche decided that he would not, on this occasion, fine Mr St George for allowing his terrier to run about loose, however he wished it to be known through the press that in future, he would fine the owner of any dog found within the Court precincts. Oh, and Mr Ding was found not guilty of larceny.

That should have been the end of it, but Mr Howard St George was embarrassed. And annoyed at Mr Pring’s attempted witticism. He wrote to the Editor of the Rockhampton Bulletin, stating that “Whilst I tender to His Honour Mr Justice Lutwyche my humblest apology for any interruption which may have been caused to him or the Court over which he presides, through the misconduct of my dog, and whilst I assure him that I had taken every means in my power to guard against such intrusion, which I beg him to believe was purely accidental, yet I must most strongly protest against any right which the Attorney-General may suppose he possesses to lecture me or any other magistrate in the manner he has thought fit to indulge in on this occasion.” So there.

A Passer-by v Mr Justice Lutwyche

Mr Justice Lutwyche had barely recovered from the indignity of having his Assize Court interrupted by a terrier, when he was publicly insulted by a very drunk German gentleman named John Rutabach (or James Rumbach, the various editions of the Rockhampton Bulletin couldn’t decide).

It was a fine Saturday evening in Rockhampton, and Mr Rutabach was taking a stroll, very much the worse for alcohol. He was creating a disturbance on Dawson Street, when two passing gentlemen advised him that he should stop making a ruckus, and go home to sleep it off. Mr Rutabach objected to this advice quite strongly, and became even louder and more profane when the two gentlemen introduced themselves. They were Mr Justice Lutwyche and Chief Constable Foran.

Rutabach, “so far from showing him any respect, grossly insulted him (the judge) and witness (Foran), and used very foul, disgusting language to both His Honour and himself.” The Chief Constable did not help matters by attempting to restrain Rutabach, and they both fell over. Mr Justice Lutwyche hurried for a constable to disentangle the men and arrest the German.

Police Magistrate Jardine fined Rutabach 20 shillings for being drunk, and 10 shillings for assaulting the Chief Constable. However, the matter of insulting a judge in public was so grave that he remanded Rutabach “in order that His Honour’s pleasure may be ascertained.”

What Mr Justice Lutwyche’s pleasure might have been is not known, as he returned immediately to Brisbane to preside over a Diocesan Committee meeting and ponder some insolvency cases.

The Rowdy Gentlemen of the Press

“We imagine no town in the colony possesses so cantankerous a clique as Rockhampton – there are one or two of the community who, like moral firebrands, scatter dissension and scandal all round, and attach to their well-conducted fellow- citizens an unenviable notoriety for which the latter are by no means responsible, or desirous of participating in.”

Queensland Times, 1864.

1863 was also the year that Rockhampton gained a second newspaper. The Rockhampton Bulletin and Central Queensland Advertiser was the original newspaper, which was launched in 1861 and edited by Mr William Hitchcock Buzzacott. The new paper in town was the Northern Argus, launched in January 1863, and published by Arthur Leslie Bourcicault. Naturally, the two publications aligned themselves with different town factions, and things became rowdy.

Mr Leith Hay v Mr Buzzacott

1862 was an eventful year for the Bulletin. On 14 August 1862, its offices burned down, destroying all its plant and equipment. New presses were quickly ordered, and put to good use in the cause of upsetting local grandees.

Early in 1862, Commissioner of Crown Lands James Leith Hay was accused of using his position to his personal benefit. Letters made their way to various editors by steamer and overland mail, defending or condemning Leith Hay, including a particularly indignant defence from George Elphinstone Dalrymple. Questions were asked in the Legislative Council and the matter percolated for months. On 22 November 1862, the Bulletin published a letter from someone calling himself “North Australia,” that contained allegations that Mr Leith Hay considered libellous. The letter was at the very least highly insulting, calling Leith Hay “the cast-off refuse of other communities” and an “official mountebank,” and accusing him of everything from corruption to mail tampering. Mr Leith Hay took Mr Buzzacott to court for false and malicious libel.

Mr Buzzacott was committed to take his trial at Maryborough in March 1863, but the Attorney-General offered no true bill in late February. The Rockhampton Bulletin could not contain its glee, describing small-town magistrates thus:

“They become the petty kinglings of the place; the swaggering, pretentious potentates of all they survey – magnificently receiving the humble homage of police flunkies, and graciously patronising the small tradesman. We do not mean to assert that such remarks as these apply in full force to Mr Hay, but there is something to induce arrogance and pretention on the part of any individual who finds himself vested with supreme authority in a small locality, and Mr Hay, being a man of merely ordinary capacity, was not proof against the temptation.”

Mr Leith Hay, writing from nis new post at Ipswich, felt moved to reply,

“I am induced to make this request in consequence of the repeated attacks by innuendo made by the Editor of the Rockhampton Bulletin on my character, which, if allowed to remain unnoticed by me, night induce the public to believe that there is some truth in them. I can only say that I am not conscious of ever having acted so as to merit the bitter and vindictive attacks made upon me by that scurrilous paper; and without the slightest dread, I can say that I dare the Editor of the Bulletin to the proof and court an investigation into my conduct as a public officer, as I feel satisfied, that should an investigation take place (which I have already demanded from the Government) it will be found that I have honestly and faithfully done my duty, and that the remarks of the Editor of the Rockhampton Bulletin are false, scurrilous, and malicious.”

Mr Morisset v Mr Bourcicault

Argus proprietor Arthur Leslie Smith Bourcicault was born in 1819 in Dublin. His younger brother was the playwright and actor Dion (Dionysius Lardner) Boucicault. The spelling of the surname differed between the brothers and their father, who seems to have been a Mr Boursiquot. Or a chap called Lardner, at least in Dion’s case (the Wikipedia entry for Dion Boucicault is, to put it mildly, a ride.)

The Northern Argus commenced in 1863 under Arthur Bourcicault’s stewardship, and, in the tradition of Rockhampton rowdiness, began alienating prominent townspeople almost immediately.

One of the first was one Rudolf Morisset of the Native Police, whom the Argus in November 1863 depicted as a teller of untruths.

Mr Morisset took exception to this, and called upon the office of Mr Bourcicault and punched him in the face. Mr Bourcicault threw Mr Morisset through the front window of his office. The scuffle continued in the street, where a passing police officer took Mr Morisset into custody. At a court hearing, the men were reprimanded and ordered to keep the peace. Both parties wrote letters to the Editor of the Bulletin, one indignant (Morisset), the other smug (Bourcicault).

This scuffle occurred as the public were still digesting the fact that four Magistrates were involved in public assaults earlier in the month. Rockhampton, it was claimed, was a place where its leading citizens resorted to “muscular argument.”

Mr Feez v Mr Bourcicault

On 1 December 1863, the Bulletin delayed its edition by several hours to report on a great fire in the town, which had destroyed stables and several shops, and a storehouse belonging to Captain Albrecht Feez.

The following Saturday, Albrecht Feez wrote a letter to the Editor of the Bulletin, humbly thanking the townspeople for their firefighting efforts on his behalf. The Bulletin was quite touched, and, forgetting the horsewhipping of Alfred Wood the previous month, wrote that “Captain Feez’s conduct as a merchant in this town and his unfailing rectitude of principle, have won for him a deserved popularity requiring only an opportunity to ensure its full exemplification.” (It would be cynical to note that Feez had recently transferred the entirety of his classified advertising to the Bulletin.)

The fire had consequences beyond physical property loss. After Feez withdrew his advertising, the Argus published a letter brought in by a man named James Crosse and signed by a dozen of his fellow labourers. It complained that Feez had not paid him or his co-workers for their work during the fire clean-up. In fact, Mr Feez had told Crosse to “go to hell.” Mr Bourcicault lost no time in publishing the letter and included a few unflattering remarks about Feez for good measure.

The next edition of the Bulletin featured an indignant repudiation by Feez, as well as a letter from Crosse disclaiming authorship of the letter in the Argus, practically accusing Bourcicault of forging it. On seeing the Bulletin, Crosse went to Bourcicault and denied that he had written the Bulletin letter in support of Feez. Bourcicault decided to march Mr Crosse to the courthouse, where Crosse swore to the truth of his original letter to the Argus.

In February 1864, Crosse was charged with perjury (relating to the Argus letter), and, after a lot of deeply confusing evidence about letters and signatures, the case was dismissed. Also dismissed was a charge of libel against Bourcicault for publishing the letter. A win of sorts for the Argus, and the only people who truly suffered were the Magistrates who had to listen to the evidence.

The situation divided Rockhampton’s press. The Bulletin was in Albrecht Feez’s corner, and the Argus was his taunting enemy. As late as March 1864, Mr Feez went to Brisbane to seek legal advice as to whether he had an action against the Argus and Mr Bourcicault. He may have been advised that it was not worth his trouble, or (a more likely scenario), he was diverted by a financial and political crisis in the Rockhampton Municipal Council.

As the decade progressed, the rowdyism continued. Separation meetings became rowdier, and the editors of the Argus and Bulletin faced each other in court for a bitter and sensational days-long libel case that ended with a £5 verdict. Some conditions improved – Mr Justice Lutwyche was never again abused by drunks in the street, or barked at (by dogs) in the course of his judicial duties.

[1] Mrs Wakefield had married Mr McDonald while he was still married. His actual wife arrived in town, discovered the unhappy news, and took her life.