Four men escaped from Moreton Bay in October 1825 – did they really commit murder, and leave five drowned comrades?

Runaway 1 – John Longbottom.

(Updated from the Post – A Notorious Rogue and Vagabond.)

At York in January 1817 a young sailor was sentenced to seven years’ transportation to New South Wales. Even for a man accustomed to sailing, the prospect of a journey to the other side of the planet would have boggled the imagination. The fact that a return voyage was out of the question probably made the sentence doubly difficult to bear.

John Longbottom was a nineteen-year-old Yorkshireman, of average height for his era (5 feet 4) and with a ruddy complexion and brown hair and eyes. It would be ten long months before he was put on board the Batavia for his trip to the Colonies. The actual journey to the bottom of the world took less time.

On disembarking in a strange dry, hot country in early 1818, the Batavia convicts were marched in chains off to a place called Windsor (that was nothing like Windsor) to be ordered into a work gang. John Longbottom chaffed at it all. He didn’t see why he should make it easy for the redcoats in charge of him.

In March 1819, for “theft and being a bad character,” he was sent by the Lady Nelson to a place called Newcastle, which, needless to say, was nothing like Newcastle.

Newcastle

John Longbottom could not abide his life at Newcastle. Whether it was the work or the overseers, or whether he was just cultivating a mean, disruptive streak, he was ordered to corporal punishment twice, and then ran away in early December 1821.

Very fortunately for John Longbottom, no sooner had his name appeared on the list of escaped convicts in the Sydney Gazette, than Sir Thomas Brisbane made a proclamation on 15 December 1821. Put simply, unless you were a really violent offender, you could come in before the end of the month and receive a pardon. Limited time only. Hurry, pardons limited.

Longbottom duly handed himself in, and, after a bit of to and fro with the Colonial Secretary’s Office, was sent to Port Macquarie.

Port Macquarie

Port Macquarie was more to John Longbottom’s liking. At least, he remained reasonably well-behaved, with no punishments or absconding for 1822. By virtue of being a summonsed as a Crown witness in a criminal case, Longbottom spent Christmas 1822 at Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney. I doubt that it was particularly festive, but a change is presumably as good as a holiday when your destiny is not your own.

The gears of bureaucracy grind slowly, and it was not until April 1823 that Longbottom returned to Port Macquarie. By January 24 the following year, Mr Longbottom was the proud owner of a Certificate of Freedom. And being John Longbottom, he did not keep it.

1825 – Imprisonment and Moreton Bay

Technically, the boat stealing incident occurred in November 1824, but for John Longbottom, it kicked off a year of determined lawlessness. It was as if the Certificate of Freedom had gone to his head, and he thought he could do anything.

On 30 March 1825, Longbottom and Charles Daley (“free, but long known as notorious rogues and vagabonds”), became agitated when placed under arrest. By now, the mere sight of a constable seemed to set Longbottom off. Several of the arresting officers were assaulted. The Sydney Bench took a dim view of this and put both men in the house of correction for three months.

That sentence had only just been served when in July, Longbottom decided that now was as good a time as any to make off with a bag of wheat from the Sydney Markets. Property crime being viewed as far more serious than roughing up a couple of constables, this offence earned Mr Longbottom a visit to the fledgling penal colony of Moreton Bay. Before leaving, he tried to break out of the yard, but was rounded up by Constable Ford, who received $20 from the Colonial Secretary’s Office for his sterling work.

The escape

The Mermaid arrived at Moreton Bay with John Longbottom on board on 14 September 1825. He managed to remain there for five whole weeks, before absconding in company with William Smith, John Welsh and Thomas Mills on 23 October 1825.

On 18 November 1825, the escapees arrived at Port Macquarie and surrendered into the custody of Henry Gillman, the Commandant there. What had happened to the runaways on their journey became a matter of conjecture.

They were placed in separate cells, and Longbottom gestured to one of the guards that he needed to speak to the man in charge. He then gave an extraordinary statement, claiming to have been part of a group of nine prisoners who seized a barge at the shingle splitters’ camp, disarmed several overseers and one soldier, then took off down the river to the sea. He claimed that his fellow runaway, Thomas Mills, had stabbed a soldier to death with a bayonet prior to taking to the boat.

On their journey south, Longbottom said, the boat floundered and was wrecked. Five runaways were drowned. The rest of the journey was made on foot.

My reason for giving this information is that I could not rest until I had done so; the other prisoners do not know I have made the confession. The Gaoler was the first person I told this to.

John Longbottom, depositions, November 1825.

Henry Gillman took the depositions and forwarded them to the Colonial Secretary, with a copy for the Attorney-General. Then nothing in particular happened.

One early report in the Sydney papers told of a murderous escape from Port Macquarie. Then the story changed. The Sydney Gazette of 01 December 1825 told its readers that the escapees had been regaling the Commandant of Port Macquarie with tales of a five-week journey by land, crossing magnificent rivers and streams. It added that the Commandant suspected that they had commandeered a boat and ditched it nearby. The prisoners, it said, would be sent to Sydney to be dealt with.

They assert that they have been five weeks on the journey, which they made nearly the whole way, within a few miles of the sea beach. They mention they crossed two very large rivers besides many smaller ones, and over very large plains many miles in length, thus they give an account of their excursion, however my opinion is that they have made their escape in a boat, I have therefore sent a Chief Constable with a soldier as far to the north as Trial Bay in hopes of being able to know the boat they have made their escape in. Commandant of Port Macquarie to Colonial Secretary, 18 November 1825

The result of the excursion to Trial Bay notwithstanding, in the coming months and years, Port Macquarie became a sort of half-way house for Moreton Bay absconders, to the great vexation of its Commandant. John Longbottom was sent to Sydney to be dealt with.

Return to Moreton Bay

John Longbottom was given another chance to enjoy the tropical delights of Moreton Bay for a couple of years, arriving per the schooner Alligator on 31 July 1827.

Longbottom would not spend long at Moreton Bay during the sentence. In April 1828, he witnessed an attack by William Clark on his fellow prisoner, James Cooper. It was Longbottom who took the axe from Clark and made sure the prisoner was secured. In September of that year, Longbottom travelled to Sydney to give evidence in the Supreme Court.

Four months later, Longbottom left Moreton Bay for good. A new Certificate of Freedom was awarded to him. Things were looking up.

But Longbottom did not go on the straight and narrow. He was quickly identified as one of the offenders concerned in a house robbery. Police inquiries resulted in another violent arrest. It was John Longbottom vs The Law again. Justices Stephen and Dowling – two of the most influential jurists of the time – gave him three years on the road in chains for larceny.

Chain Gang

Shortly after starting on the road gang, Longbottom absconded, earning himself 50 lashes. He then started a riot – as one does – and earned himself 200. He wrote to the Sydney Monitor, which was largely unsympathetic. Given the Editor’s antipathy to Captain Logan, Longbottom should have mentioned that he was once at Moreton Bay if he wanted a kinder reception.

We have received a letter from a prisoner named John Longbottom, of No. 5 Iron Gang, in which he narrates a small affair for which he says a Magistrate of the name of Lamby, (so he spells the name) ordered him 50 lashes. That the Overseer had him up again for creating a riot, and that Justices Atkinson and Lamby, sentenced him to 200 lashes. That in flogging him the scourger stopt once or twice, giving it as his opinion (as the best judge in the absence of the surgeon) that his back was so bad he could not take all the punishment at that time. But the Constable said he must obey his orders, and so the scourger completed the sentence. Of course, we do not vouch for the truth of this letter of Longbottom. But we think it right to publish his statement under all circumstances. He says (of course) that so far from being guilty, his accuser the Overseer had first maltreated him and then complained of him to the Justices. It is however to be remembered, witnesses on the part of Iron Gang Convicts are not allowed to be called by them. The accusers (under the Code Darling) have it all their own way. Sydney Monitor, 26 January 1831

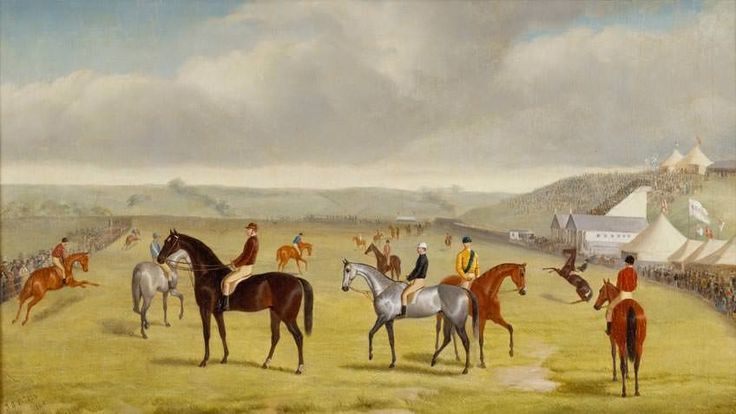

A Fracas at the Races

The Monitor couldn’t help Longbottom, so he absconded from his work gang again. This time, he managed to be arrested in the wash-up of a particularly riotous Race Day in Sydney. True to form, Longbottom did not go quietly.

That Race Day was attended by free citizens and the military, a lot of money changed hands and a lot of alcohol was consumed. The police were on the alert.

By 10 pm, the revels were still in progress, and that was the time that John Longbottom, a fugitive from the law, decided to enter one of the booths. One look at the people in the booth made him turn his face away – constables all over the place. Too late. Constable James Orr, who had seen him full-face said, “Ah, Longbottom, is that you?”

Longbottom’s reply was to draw his knife and attack Orr. Another constable, Richard Nagle, came to Orr’s aid, and a melee ensued. The crowd took Longbottom’s side and helped him get away. Four determined constables legged it after the fugitive, and eventually, after a scuffle with a knife (Longbottom’s) and a cutlass (Orr’s), the prisoner was captured. Constable Nagle was cut so badly on the hand that it was thought he might lose the use of it.

The prisoner was found guilty on the charges of stabbing with intent to maim, intent to do grievous bodily harm and resisting lawful apprehension. Longbottom was given the death penalty.

The Governor granted clemency and on 16 July 1831 commuted death to being worked in chains at Norfolk Island. For the term of his natural life.

Norfolk Island, Cockatoo Island and Vagrancy

Surprisingly, John Longbottom does not appear in the accounts of the Norfolk Island prisoners’ mutiny in 1834. Ten years earlier, this would have been just his idea of a day’s fun. Perhaps he didn’t get along with the ringleaders, perhaps he had his first attack of common sense in decades, perhaps he just couldn’t care anymore.

In 1842, a middle-aged Longbottom was transferred from Norfolk Island to Cockatoo Island, Sydney, as part of the transition to freedom.

He still struggled with the law. One charge of being a vagrant in 1846, against which he argued manfully in Court, gained him a month indoors with bed and meals provided. In 1850, Longbottom was charged on summons with assaulting a police officer. It wasn’t a serious violent assault, and he was given the chance to make reparation in return for the charge being vacated. But the law still won. John Longbottom had no goods and chattels to sell, so he spent two months in Parramatta Gaol.

After that, John Longbottom had very little fight left in him. He was over fifty and had spent nearly four decades fighting the law and losing.