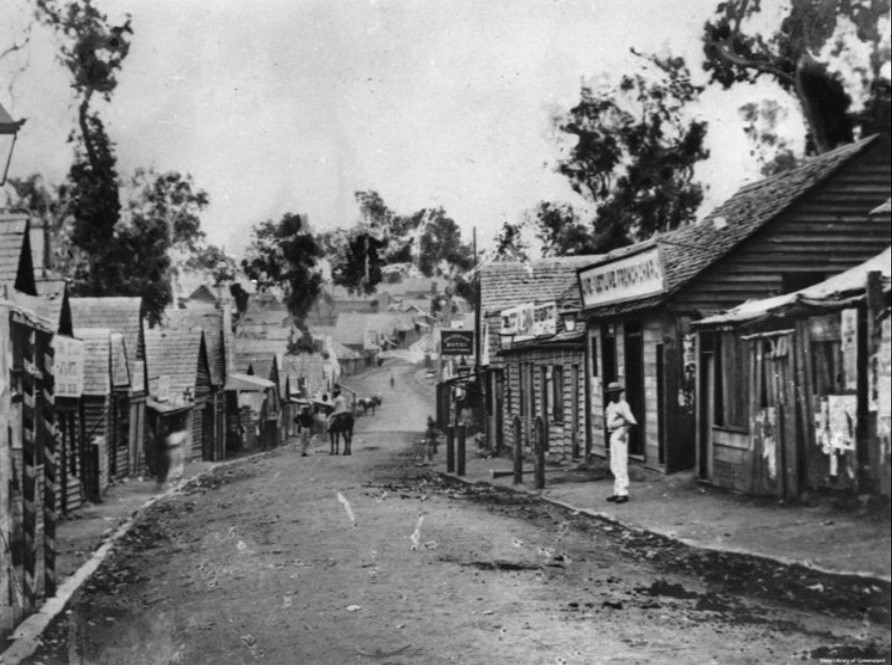

Mr W Selwyn King had received orders to return to Sydney from his posting at Kilkivan, near Gympie. It’s hard to imagine that he would be particularly reluctant to leave the remote town, but he had made good friends during his stay, and they toasted him at a farewell dinner at the Northumberland Hotel. The following morning, Wednesday 6 January 1869, his friends and well-wishers waved him off as he left town in the Gympie Cobb & Co mail coach. Little did anyone present suspect that their next meeting would be only a few hours away.

When the coach left Foo’s Hotel on the journey to Brisbane, there were seven passengers on board. They included Mr Thomas King, a former local merchant; Mr Walker, a local miner; and Mr Freeston, of the Sydney firm Freeston and Kidgell. Along for the journey was a decidedly tipsy young man, who had brought a few beers along to combat the January heat in the enclosed coach.

Five miles into their journey, two men emerged from behind an ironbark tree. They wore masks and were armed, and ordered the coach driver to stop or they would fire. They were bushrangers, wearing the accepted “uniform” of the Australian highway robber – moleskin trousers, coats and felt hats. Presumably all bushrangers dressed that way to avoid the inconvenience of being mistaken for missionaries or wandering poets.

One of the bushrangers was tall and thin, the other shorter and thick set. Their faces could not be seen by the passengers.

Mr Selwyn King, by now accustomed to travelling in the Queensland bush, had a revolver in his possession, and immediately drew it, and, reaching across the other passengers, aimed and fired at the closest robber, the shorter man. The bushranger fell back, but still fired off a couple of rounds into the coach – one hit Mr Walker through the wrist, another whistled by Selwyn King’s nose, and the last landed in the frame of the carriage.

As the shorter of the two bushrangers tended to his wounds behind a tree, his taller companion covered Mr King with his weapon, and ordered the passengers out of the coach, with instructions to remove and empty their coats and waistcoats of any money and watches they might possess.

Mr Selwyn King apparently had the presence of mind to secrete a bag of gold in his boot and his pocketbook. He also hid his gun in the folds of his shirt.

Mr Freeston, it was reported, had hitherto been quiet, but on emerging from the coach, cried out, “It was not me who fired. I have no revolver. It was him inside,” indicating Mr Selwyn King.

The drunk young man had been rather bemused by the whole business, until he sobered up enough to instruct Mr Selwyn King to “aim better,” and got up suddenly. The taller bushranger turned his weapon in the drunk’s direction, as Selwyn King took the opportunity to grab his revolver and fire several shots at the highwayman.

He hit his target, who roared, “Oh! you ——- dog!” as Mr Selwyn King, out of ammunition, took to the bush and kept running. Swearing vengeance upon King, but understandably reluctant to chase him while suffering gunshot wounds, the robbers took up the contents of the passengers’ pockets, neglected to search the coach, and rode off in towards Gympie. Mr Selwyn King, walking through the bush, noticed the two bushrangers on the road, both injured. When they were out of sight, King made his way to a nearby stop, where he met the coach and his travelling companions. From there, the party went back to Gympie, where Mr Selwyn King had some astonishing tales to tell his old friends, and the local police.

The Gympie Times joked that, “We believe that it is in contemplation to petition the Queen to grant Mr. Freeston the Victoria Cross, as a reward for his valour. In the meantime, the least that can be done is to invite him to a public dinner.”

Mr Freeston wrote to that paper’s Editor, complaining of his treatment, saying “a baser calumny was never uttered.” Hmph.

Ten days after the hold-up, one of the bushrangers was in custody. He was the shorter, stouter man, and was identified as William Bond. A doctor gave evidence that the injury Bond was suffering came from a bullet wound. Mr Thomas King identified Bond as the culprit from his build and the sound of his voice. Bond spent a miserable nine months in custody as his case was remanded again and again – Mr Walker was in hospital, other witnesses were in Sydney, his own witnesses were unavailable. Finally, after a strong cross-examination of identity witnesses in the face of a determined Ratcliffe Pring, the undefended Bond was found guilty of robbery under arms and sentenced to 20 years in gaol, and 50 lashes.

But what of the other bushranger? It turned out that he was named Palmer. At least three people were arrested on suspicion of being Mr Palmer, a bushman concerned in the robbery. The various Palmers were apprehended hundreds of miles from Gympie by gallant police officers who travelled across flooded rivers and dirt roads to get their man.

In June, the apparently correct Mr Palmer was arrested, quite close to Gympie, but by the time the police had their hands on him, they weren’t worried about the Cobb & Co robbery. He was now wanted for the murder of the gold carrier, Patrick Halligan, near Rockhampton. He was George Frederick Palmer, a New South Welshman of good family, who fell into doubtful company at Rockhampton, and parlayed his excellent horsemanship into a career as a bushranger.

As Bond went to trial in Maryborough in October 1869, Palmer was tried the same month in Rockhampton, and was sentenced to death. Palmer’s death sentence was carried out at Rockhampton Gaol in November 1869. Bond ended up at St Helena Island, where his admission register showed that he was a sailor aged 41, a recent arrival from England, 5 feet 4 ¾ in height, medium build with a dark complexion, brown hair and grey eyes. It was noted that he had a scar across his temple, some teeth missing, and a gunshot wound on his ribs.