On this day, 4 February 1882.

Brisbane had been drought-stricken for months. A gentleman named Professor Pepper had a scientific idea – “tapping” the clouds that had hung low over the town, but which had failed to produce a drop of rain. The idea involved an iron-framed kite, cannons and rockets. A donkey was present. Nothing went to plan. The Courier was present to observe the proceedings.

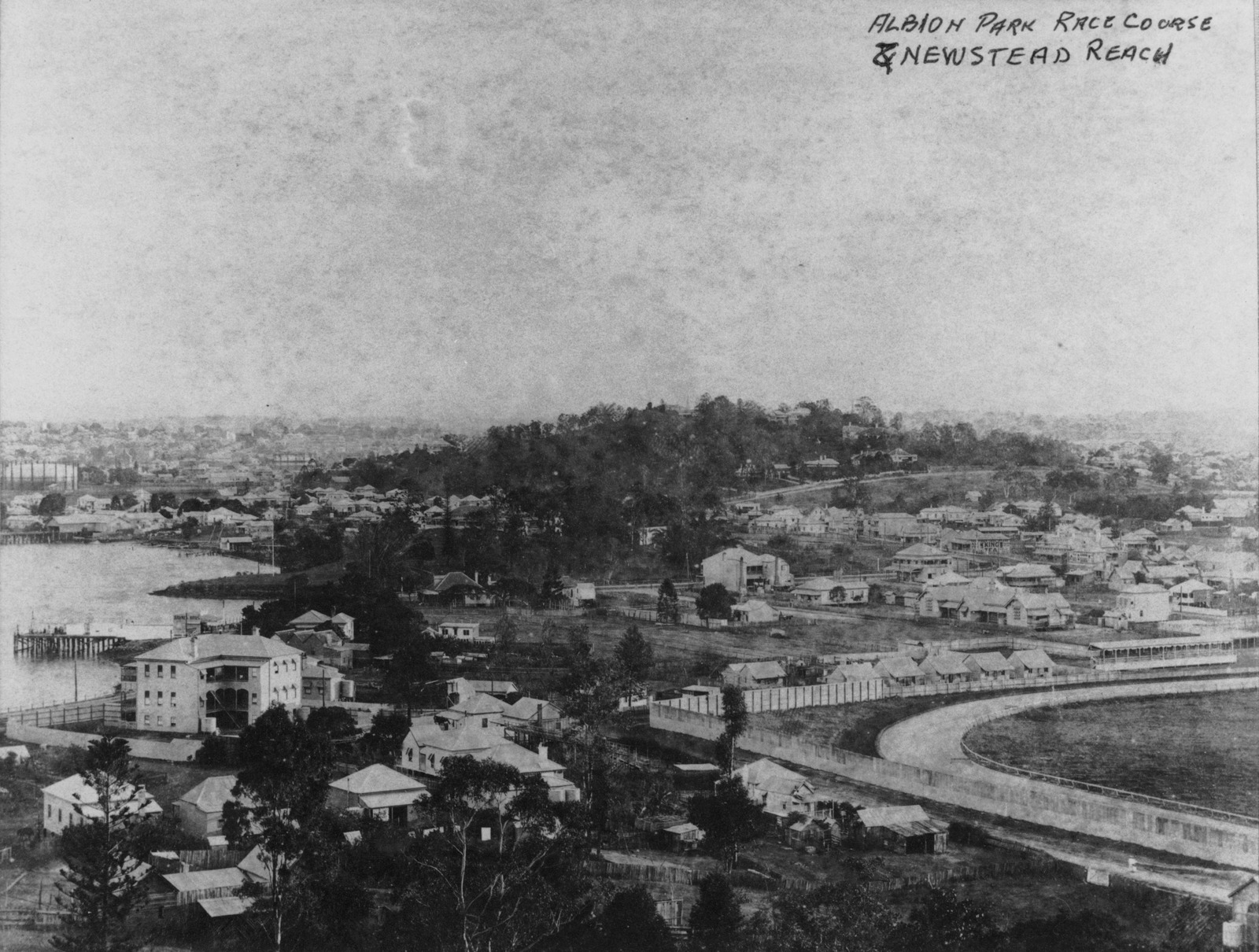

Professor Pepper at the Racecourse.

On Saturday the racecourse was attended in the afternoon by some 600 or 700 persons, who went there in order to witness the series of scientific experiments, and especially the novel feat of “tapping the clouds” by means of a gigantic kite and concussion promised to be attempted by Professor Pepper.

The main feature of the affair was a complete failure, and the experiment which the professor expressed his desire to attempt was not tried, although the atmospheric conditions were most favourable, heavy rain clouds hanging low and a steady breeze blowing nearly all the time.

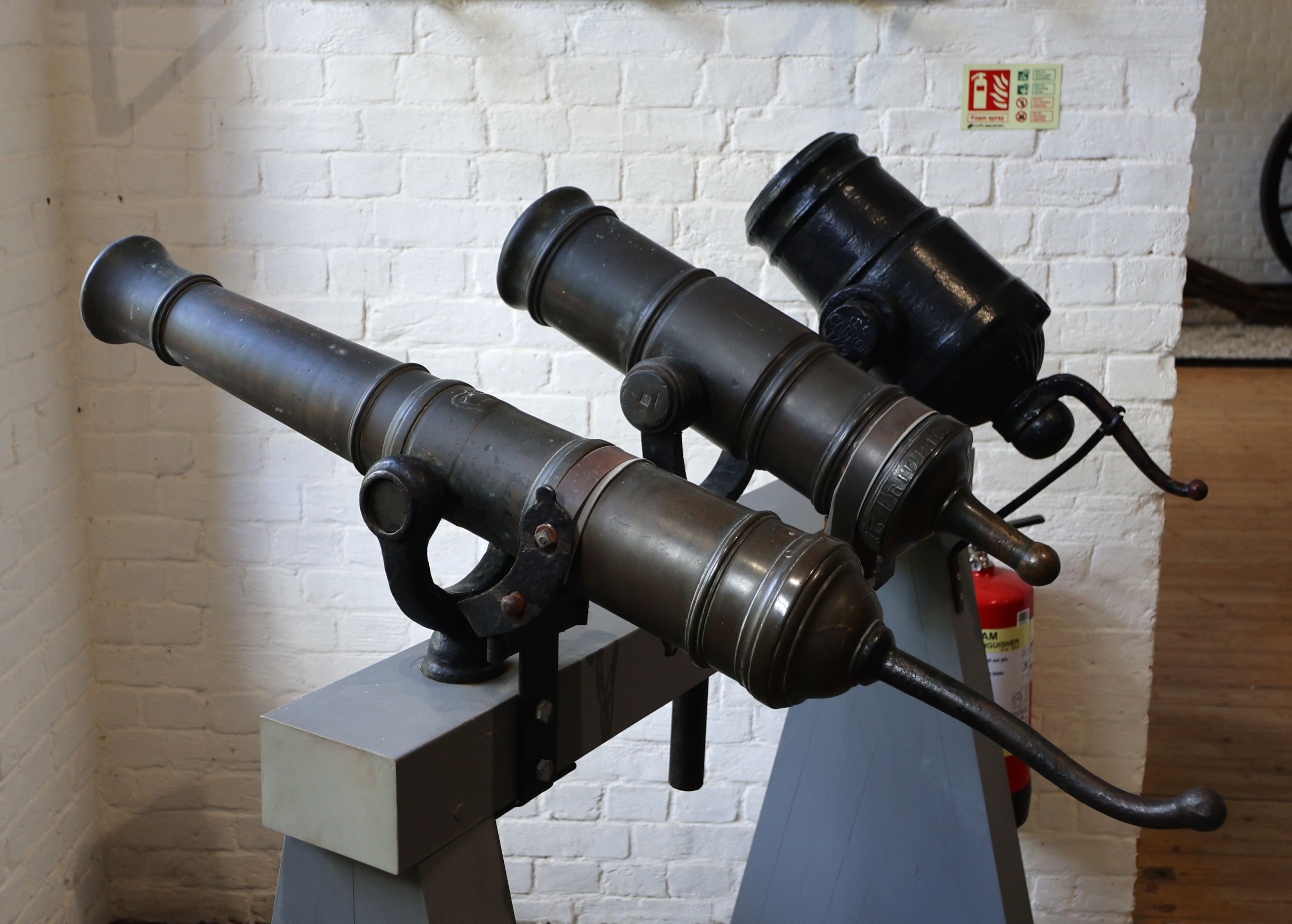

On arriving at the ground, preparations of different kinds were visible, an anemometer[i] for indicating the velocity of the wind was at work, and an electrical machine was in readiness for use. There were also fixed on posts ten small swivel guns[ii] of an antiquated pattern. By noon a commencement was made by the explosion of a small charge of dynamite by electricity, and two or three large rockets were fired. The swivel guns were fired separately at intervals during the afternoon, no attempt being made to produce a concussion by firing them simultaneously by means of electricity.

From left to right: Photograph of Albion Park Racecourse and Newstead, c. 1900 (John Oxley Library); Anemometer, 1899, Johns Hopkins Press; Swivel guns, Wikipedia, photo by user Geni.

Shortly after 2 o’clock the first attempt at kite flying was made. The kite tried was a square calico one, with a heavy piece of batten laid crosswise and fastened with iron for a frame. It would scarcely be believed that it could have been thought possible to make such an affair rise from the ground in anything short of a hurricane; every effort to do so resulted in utter failure.

Shortly afterwards a few more rockets were discharged, and a large charge of dynamite was exploded. Two of the rockets were very carelessly handled. One went over the fence of the course, and exploded on the ground, and another took an erratic flight in the opposite direction, fortunately out of the way of the crowd, or a serious accident might have occurred. The people became clamorous for the “great experiment” of the day, an event that had been anxiously expected, “the raising of the huge kite that was to have tapped the clouds.”

This proved an even more conspicuous failure than the preceding attempt. Nothing would induce the unwieldy affair to leave the ground, and the efforts to raise it were greeted with shouts of laughter. At last, the jeering crowd took possession of the whole affair and tried their hands, but with no greater success. In fact, the good humour of the spectators was remarkable, in many places a similar public disappointment would have raised angry feelings. Not a little of their good humour was due to the laudable exertions of a lady professor of the art of equiponderant disturbance[iii], with the assistance of a highly trained donkey, which created infinite fun by the skillful manner in which it flung off all who attempted to ride on it. This and the excellent playing of the Artillery band served to divert the crowd and induced them to regard in a merciful spirit the pseudo-scientific fiasco they had come to witness. Friends of the professor’s, however, declare that the rain experienced since Saturday last is due mainly to his exertions, and from his letter in another column it will be seen that he has something more to say for himself.

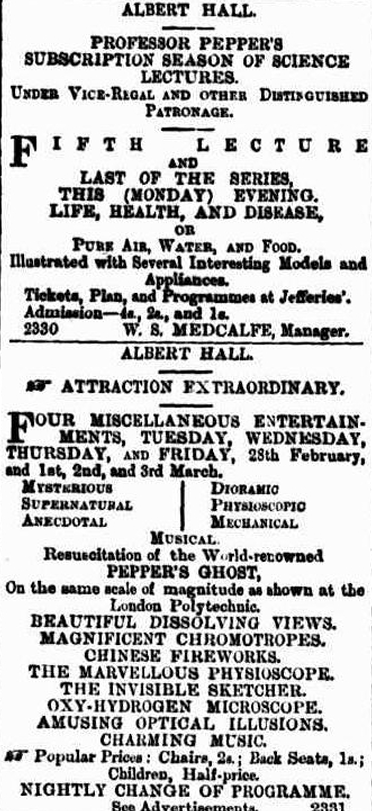

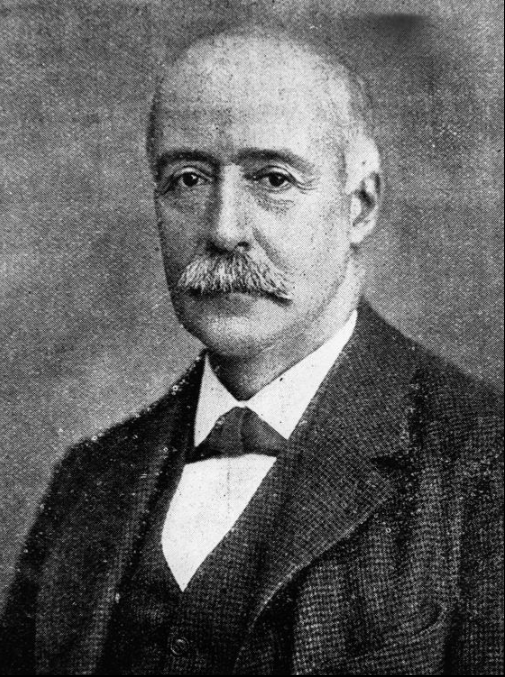

Professor John Henry Pepper (John Oxley Library); Advertisement for Professor Pepper’s Subscription Lectures, Brisbane Courier, 27 February 1882.

Professor Pepper? Firing rockets at clouds? Surely this was the work of another faux academic carnival character, like Professor Russell[iv], or Doctor Norman. [v] But no, John Henry Pepper was an academic, albeit one with a fabulous line in theatrical entertainments.

Professor Pepper c 1870 by Henry Maull (London). Professor Pepper in later years (John Oxley Library).

Pepper was born in London in 1821 and attended King’s College School. He developed an interest in chemistry and lectured at the Grainger School of Medicine while still in his teens. In the 1840s, he began giving lectures at the Royal Polytechnic Institution, and later became its director.

Pepper lectured around the English-speaking world throughout the 19th century and had a particular interest in public education – providing scientific and academic lectures to anyone who had an interest (and a few shillings). He had a flair for theatrics and created the sensational “Pepper’s Ghost.” [vi] The ghost effect involved using angled mirrors and light to project the movements of an actor concealed below the stage to show a ghostly apparition seemingly interacting with the live actors on stage.

Professor Pepper and his family settled in Brisbane in the early 1880s, where he was appointed Government Analyst. The house built by Professor Pepper, “Woodlands,” still stands in suburban Ashgrove and is heritage-listed. In 1889, Mrs Pepper’s health necessitated a return to London, where the family remained until Pepper’s death in 1900. There is a charming interview with him in the Pall Mall Budget below.

Professor Pepper at the Polytechnic. An Interview with the Professor – not his ghost.

Professor Pepper, erstwhile of Brisbane, has been interviewed on his arrival in England by a representative of the Pall Mall Budget. The scribe writes: –

“The Polytechnic and Pepper! How naturally the familiar conjunction flows from the pen, and what bygone enjoyments it conjures up out of the long ago. So far as London is concerned, the famous scientific entertainer has been absent from it so long as to make it widely supposed that the good man has indeed become “Pepper’s Ghost,” and positively to a large portion of the rising generation his very name-to say nothing of his fame – is unknown. To-night, however, by a strange combination of circumstances, the Professor’s foot will once more tread his “native heath” at the Regent-street institution, when he has arranged to give a lecture of the old type so well-known and so much frequented before the Young Men’s Christian Institute had taken up its quarters at the Polytechnic.

“In the course of a chat with the ruddy-faced white-haired Professor a representative gleaned from him some interesting reminiscences and reflections. “It is exactly ten years,” said the erstwhile Prince of the Polytechnic, since I left London, where my ghost performance sprang into popularity about a quarter of a century ago. I and my family have been living at Brisbane, Australia, for the last ten years, and my wife’s health was the chief reason of our return. We had a large and comfortable ‘place’ out there. Neighbours would often send in, asking’ me to let them have half a dozen trees, which I gave with as little thought as if they had been cauliflowers in England. I was appointed analyst to the city and used to have fine fun when people tried to bribe me-all in vain, of course-not realising that all samples reached me simply with a number attached, affording no clue to identification. I lectured a little, including some lectures of a more serious scientific character than I usually give. And, by the way,” he continued, “that reminds me of one of the leading principles of my old entertainments at the Polytechnic – I have always tried to steer the ship so as to give plenty of entertainment, while never forgetting the freight of science that we had to throw overboard. Had it not been for weak management, the old Polytechnic would still be in existence and flourishing. But £30,000 was lost there in fifteen years, and that is not a small sum; considering it, I have all the more admiration for Mr. Quintin Hogg’s lavish outlay; it is not every day in the week that one comes across such a man.”

“I spent five years in America, where such lectures as mine proved a decidedly attractive novelty; but their powers of drawing everywhere have always been great; indeed, my ghost illusion has realised many thousands of pounds from first to last.”

:And then the worthy Professor, mentioning the expenses attendant on his scientific training in the state of such matters in his young days, spoke about his small but faithful band of actors and actresses, especially of one young lady who used to play the leading parts in the Pepperian dramas. She went on and on, now as Queen, now as mermaid, then as peasant, and what not, until something like twelve years had passed, when she grew so stout that audiences laughed at her ultra unromantic appearance, and her marriage and retirement occurred -she was a worthy soul,” said Mr. Pepper with a genial smile. The Professor will shortly give other lectures in other places, and a fortnight’s entertainment, with the resuscitated “ghost,” at the Polytechnic at Christmas. Fortunately, he has no need to lecture, but is a firm believer in not getting rusty.” With some cordial praise of the present Polytechnic laboratory, Mr. Pepper, with thanks for good wishes, then hurried off to look after his preparations for to-night; “for,” said he, “after a long rest, such as I have had I have to pull myself together to make the thing go smoothly.”

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Monday 6 February 1882, page 3. Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 25 December 1889, page 7.

[i] An Anemometer is a device to measure wind speed and direction.

[ii] A swivel gun is a small cannon mounted on a stand that allows it to have a wide range of movement.

[iii] Presumably this lady was there to observe balance, and the effect of its disturbance – equiponderant means evenly balanced.

[iv] A hairdresser, amateur dentist, and brothel owner, who had a sideline mail order business in pills for “female problems”.

[v] An unregistered, and very probably untrained, medical man alias Dr Hope alias Samuel Abrahams, who, between stints in custody, lectured on phrenology.

[vi] Well, he took a theatrical trick created by Henry Dircks and improved upon it and amplified it. The two men worked as a partnership for a time, until professional jealousy, combined with Pepper’s self-promotional instincts, split the partnership. Dircks was extremely bitter as he watched “Pepper’s Ghost” become a worldwide sensation.