On this day, 9 April 1883.

On 9 April 1883, the Edison company conducted the first ever demonstration of electric lighting in Queensland at the Government Printing Office, Brisbane. The representative of Edison was the wonderfully named Major S. Flood Page (General Manager, Edison’s Indian and Colonial Electric Light Company, Limited of London).

The language used by the journalist covering this event shows just how revolutionary electric light was. Candlepower was the unit of measure used to describe the brightness of light (based on a 75-gram candle burning at 7.8 grams per hour, according to the UK Metropolitan Gas Act 1860). The mention of a “8.5 horsepower dynamo machine” powering the display is particularly quaint and charming and describes what sounds like an early generator.

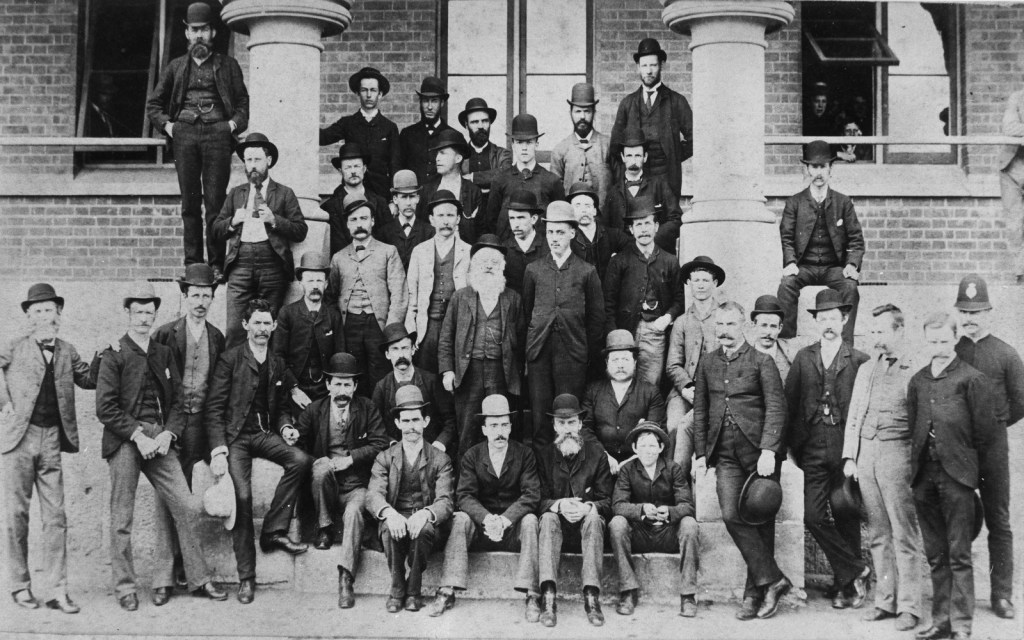

Around 80 men and women (accustomed only to gas and candlelight) assembled in the William Street Printing Office to see what all the fuss was about. The Edison lights they came to see had been set up and tested by the Office’s compositors, who were impressed by how cool and bright the lights were, compared to gaslight.

There were two distinct kinds of lights – one the arc light, and another the incandescent, or, as it is often called, the “glow” light. The arc light was that great, big, hideous light that everybody detested, which threw great shadows that hurt the eyes, and which all the ladies said made them look pale and deathlike.

For his own part he was old enough to know that what ladies did not want men could not get, and as ladies would not have the arc lamp, there was not much fear of the arc lamp coming into general use. On the other hand, he was quite right in saying that there was no lady in the room who would object to stand under the soft glowing light they had there.

Brisbane Courier, 10 April 1883

Nobody likes harsh lighting – even, one suspects, a gentleman – however the preference for incandescent light was laid at the feet of those vain creatures, “the ladies.”

Another point in favour of electric light was that it didn’t consume oxygen in the same way as gas lighting. Major Flood Price proclaimed that:

The glass in which the electric light was burning being hermetically sealed, there was no consumption of oxygen, and what amount of oxygen Providence had allowed to each person, Mr. Edison could always allow them to have to breathe.

Brisbane Courier, 10 April 1883

After the demonstration, and a light supper, Brisbane went home and considered the prospect of having as much oxygen as Providence and Mr Edison allowed. Brisbane liked what it had been told, and went all in on Mr Edison, particularly in the Parliamentary precinct in William Street.

Work commenced the following year, and finally in May1885, Parliament was lit, after Edison cables were laid underground, linking the “dynamos” at the Printing Office and Parliament House. This was the first underground electrical cable system in the country.

Those present at the first electric lighting of the people’s house noticed the place was much cooler and brighter.

The first feature calling for comment being the entire absence of glare and heat hitherto so apparent. More especially was this noticeable in the debating Chambers of the House where heretofore the light was obtained from a number of gas jets forming a “sun” from which the heat and glare were very noticeable. The change is now most agreeable, the light being more penetrating, but less trying to the eyesight.

Brisbane Courier, 20 May 1885

Nearly 140 years later, Edison’s tubes reappeared in an unexpected manner. Construction workers in the Queen’s Wharf site in 2018 uncovered the network of cables, long forgotten, under William Street. Archeologists and historians were called in, and it was discovered that these cables were extremely rare, and remarkably well-preserved. The discovery was so important that the cables were carefully divided, and sections have found their way into museums in London, the Edison National Historical Park, and throughout Australia.

1 Comment