In 1871, Charles Dean married Temperance Bouchard at Fortitude Valley in Brisbane. Nothing terribly unusual about that – both were single and of marriageable age. However, the backstory of their lives, and how they came to meet and eventually marry each other is quite extraordinary. The groom was a Singapore-born Chinese businessman and interpreter. The bride was from the Huguenot silk weaving community in London’s East End.

The Huguenot Silk Weaver’s Daughter.

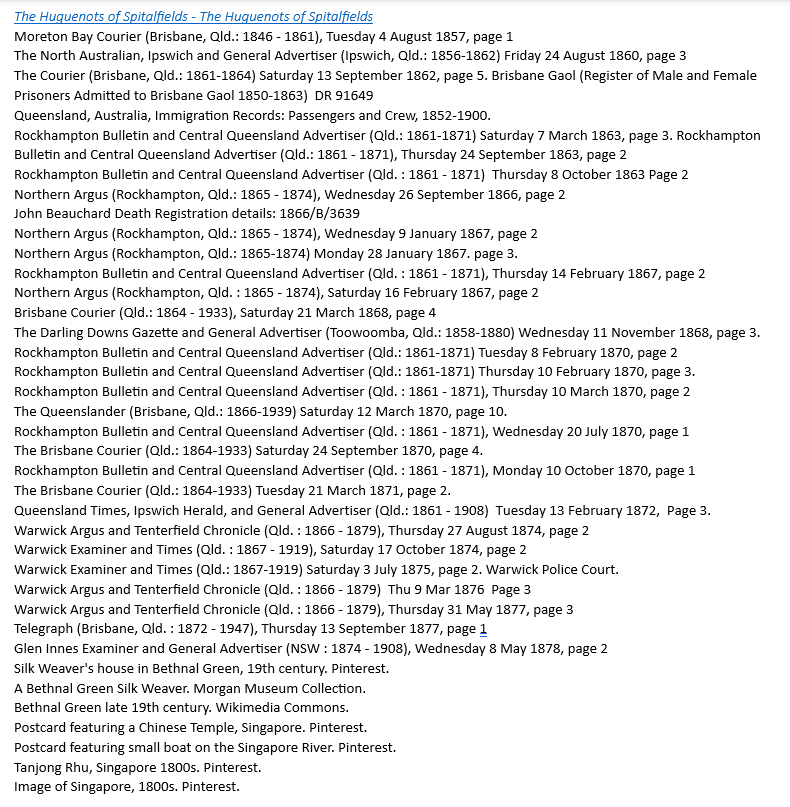

Bethnal Green

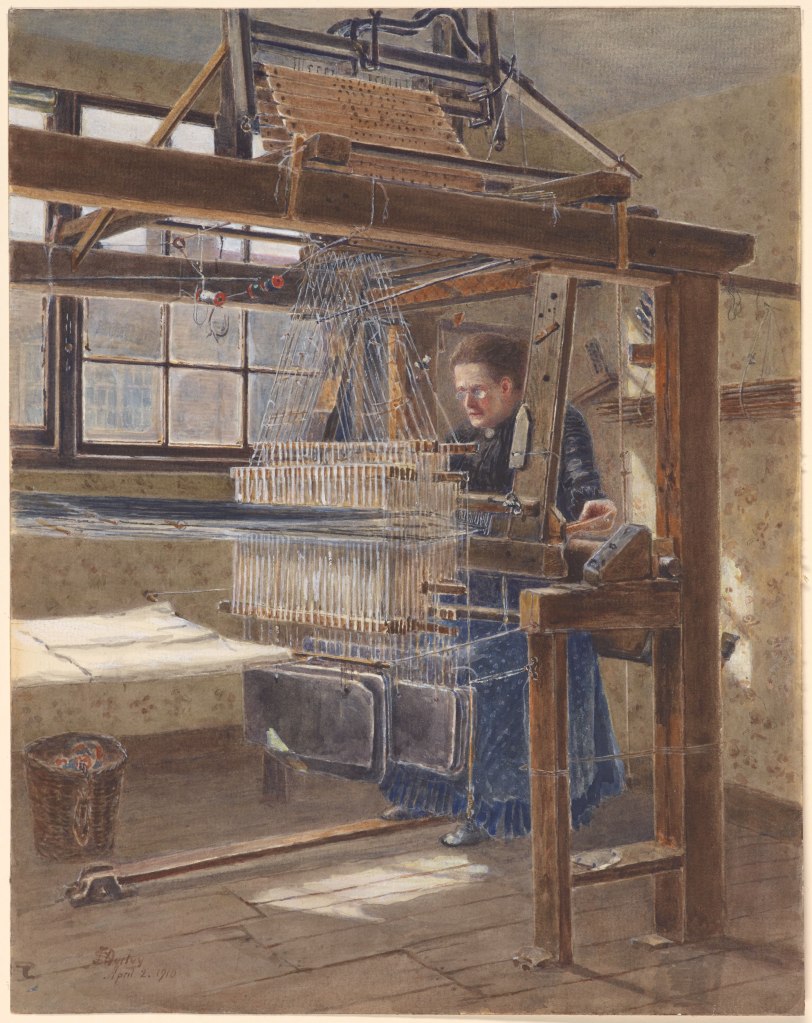

Just off Castle Road, close to King Street and Duke Street, and travelling all the way to the newfangled Eastern Counties Railway line, was Turk Street, Bethnal Green.

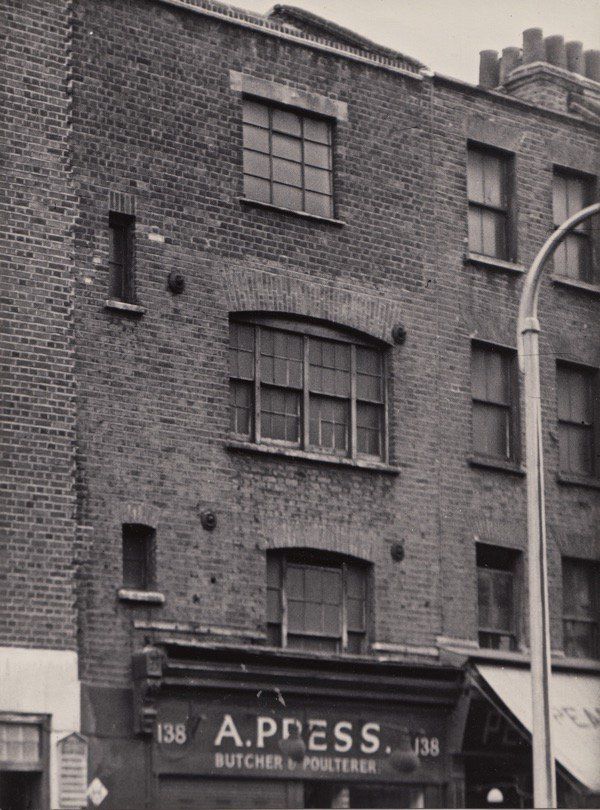

Number 12 Turk Street was home to several families of journeyman silk weavers and their lodgers. There were the Houghtons, the Hunts, and the Huguenot[i] Bouchard family. Josiah Bouchard was a silk weaver, as was his wife, Eliza. When the 1851 census was taken, they had two children, Temperance aged 4, and Alfred aged 10 months.

Multiple families living in one small dwelling was the norm for the East End’s artisan silk weavers. Large silk looms dominated their rooms, leaving only a small amount of space for family living. The squalor associated with living at close quarters was somewhat abated by the need to keep the silk clean for weaving, but it was hardly pleasant for so many people to live on top of each other.

In the 1850s, living standards in the East End deteriorated further, and some streets were becoming slums. By 1863, the Bouchard family had grown to seven. Faced with the decline of the British weaving trade[ii], and the crowding and poverty of the area, Josiah applied for assisted immigration, and took his family to a place in the colonies called Queensland.

Just before their departure, Temperance was christened at All Saints, Stepney, something that had apparently been neglected in the previous seventeen years. Perhaps the prospect of a long sea journey and a life on the other side of the world compelled Josiah and Margaret to do something about their daughter’s immortal soul. Events would prove that the divine blessing had little practical effect.

The Bouchard family arrived in Brisbane aboard the Star of England in 1863. Young Temperance was sent out to work, as any useful young immigrant would be. She was unable to write, but would be suitable for domestic work.

In 1864, Temperance was hired as a servant to a Chinese man who kept a boarding house in South Brisbane. The man’s anglicised name was Charles Dean, he was still in his twenties.

The Sea Captain’s Son.

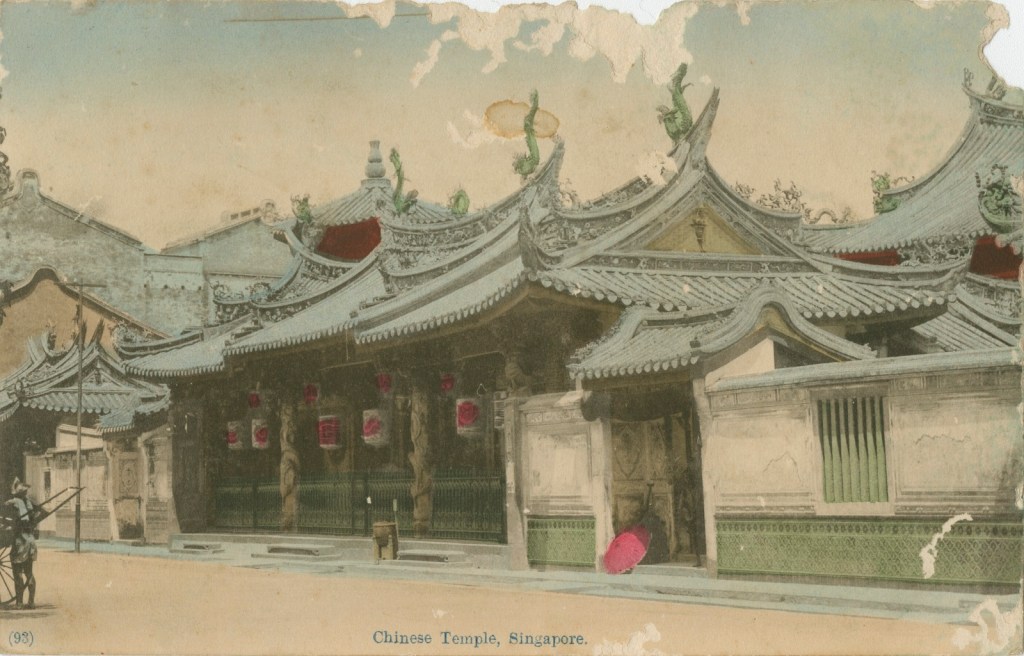

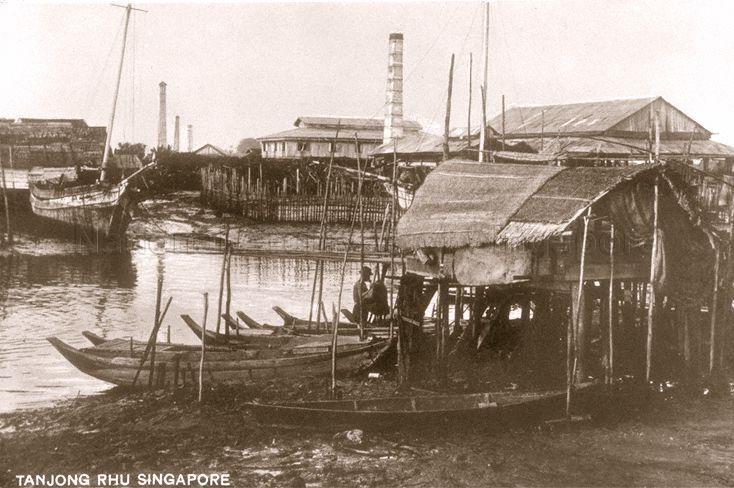

Singapore.

Charles Dean (or Deane, Deng, Din or Ding, depending on which European person was recording his name) was born in Singapore in 1838. His father was Hong Din and his mother Ah Way, or Sada Honey. Hong Din was a sailor and ship’s captain and was part of Singapore’s Chinese diaspora community.

Just twenty years before Charles was born, the British Empire – in the person of Sir Stamford Raffles -decided that the island of Singapore would be an ideal spot to set up a port to secure the lucrative trade route between (British) India and China. And it would put paid to those Dutch scoundrels monopolising sea trade in the region.

Sir Stamford pounced, and the trading post was secured with a spot of imperial chicanery also known as a treaty. Raffles’ stratagem worked – trade boomed, and in consequence, the population of the island grew from a few thousand local inhabitants in 1810 to tens of thousands of Malays, Indian, and Chinese settlers. Growing up in this dynamic, multicultural, multilingual society gave Charles the language and business skills he would use in later life.

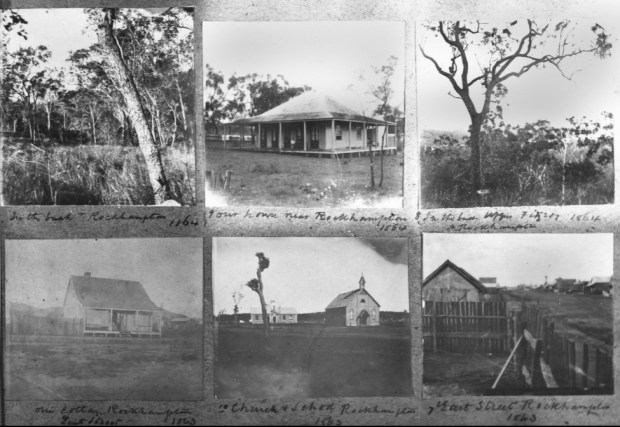

Early life in Queensland.

Exactly when Charles arrived in Australia is hard to pin down[iii]. He was in his late teens when he was first recorded as living in Brisbane in January 1857, and seems to have worked as a cook before setting up the boarding-house at South Brisbane in the early 1860s.

Charles was part of the first wave of Chinese immigrants, who were welcomed as saviours by settlers seeking workers who were not drunken, shiftless ex-convicts from the Old Dart. Although there were clashes of language and custom, the era of organised anti-Chinese sentiment was still a generation away.

Some of the many Chinese workers and businesspeople in Queensland, 1800s.

Charles Dean’s English and Chinese language skills led to him being called upon to act as an interpreter for Chinese people appearing before the Courts. The first trial of Charles’ interpreting career was also the most serious. In August 1860, a Chinese shepherd named Kimboo was tried for the murder of Garrick Burns at Clifton Station on the Darling Downs.

At 22, Charles Dean found himself assisting a defendant before the Supreme Court at Brisbane. From the press reports, Charles did a workmanlike job interpreting the procedures and evidence to Kimboo[iv], including explaining the right to challenge jurymen before they were sworn.

Charles’ services were called upon more frequently in the 1860s, and he was officially gazetted as the Government Chinese Interpreter, a position that he treated as both an honour and a responsibility.

Beginning a family – 1863.

Traditional and more westernised Chinese families in 19th century Queensland: Left, Kwong Sue Duk with his 3 wives and 14 children; Right, Mee Yong Tom and her younger sister Annie with their father Tam Hung (SLQ).

“Our Clerk of Petty Sessions, Mr Ravenscroft, was again called upon to perform the holy ceremony of marrying a Chinaman to a blooming rosy girl here, a native of the Emerald Isle. This is the fourth couple of that sort living here, and all seem as yet happy and contented.”

Drayton correspondent, Moreton Bay Courier, 1857

In 1861, a seventeen-year-old domestic from Ayrshire arrived in Brisbane on the immigrant ship Persia. Mary Ann Potts was among the thousands of very young women who travelled alone to the other side of the world to find employment. She went into service in Maryborough but found herself in trouble for stealing items amounting to £5 in 1862. The frightened teenager pleaded guilty at the first opportunity and was sent to Brisbane Gaol to do three months’ hard labour. She was discharged in December 1862.

How, when and where Charles Dean and Mary Potts met is lost to time, but in March 1863, the Reverend Samuel Savage conducted the wedding of Charles Dean and Mary Ann Potts, according to the rites of the Congregational Church at Rockhampton.

In 1863, newly-married Charles also found himself in trouble with the law, charged with stealing a piece of holland (cloth) from Mrs Goodwyn at the Clarence and Eagle Hotel. No-one saw Charles take the cloth, but he was seen carrying a roll of cloth one evening. Mrs Goodwyn missed her roll of holland some days afterwards and decided that of all her recent guests it was Charles who had made off with it. He was committed to take his trial at the Rockhampton Assizes in October 1863.

At the trial, Charles’ name was reported as “Ding” in the papers. As luck would have it, the Ding/Dean case was being heard when Magistrate Howard St George’s terrier bounded into the courtroom, eager to make new friends. Chief Justice Lutwyche was irritated by the canine interruption to the dignity of the Court, and Attorney-General Ratcliffe Pring made a joke at Magistrate St George’s expense. Magistrate St George defended his, and his terrier’s, honour in the Letters pages. Oh, and Charles Dean was found not guilty of larceny.

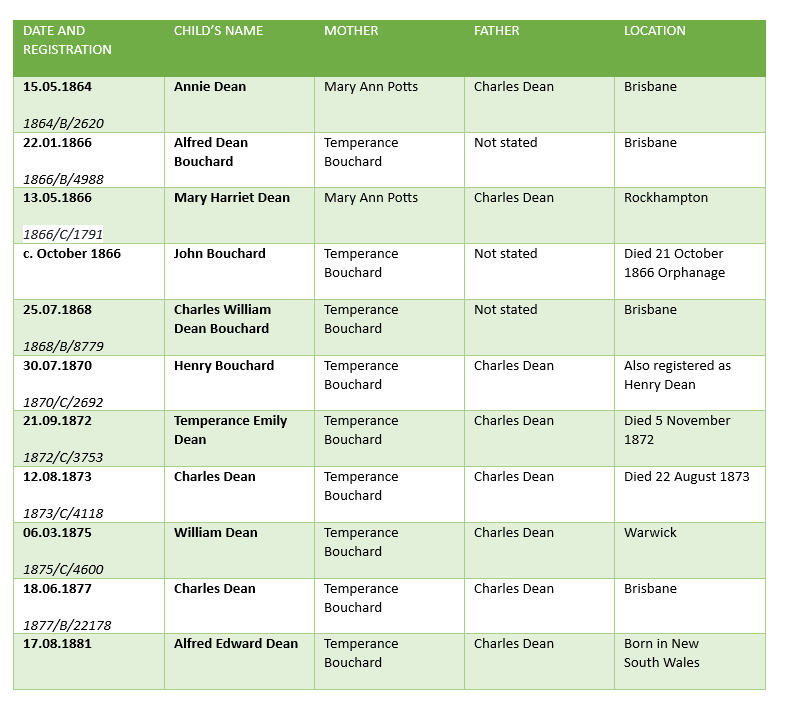

Charles and Mary Dean welcomed their first child, baby Annie, in May 1864. So far, so good.

In September that year, Charles Dean, back in Brisbane, met and employed Temperance Bouchard. In December 1864, Charles was taking out advertisements in the Brisbane Courier, refusing to be responsible for his wife’s expenses. The two events were not unconnected.

Affiliation – 1866.

On 22 January 1866, Temperance Bouchard gave birth to baby boy she named Alfred Deane Bouchard. One month later, Temperance summoned Charles Dean for maintenance, and the Courier reported:

AFFILIATION. -Charles Dean (a Chinaman) was summoned to show cause why he should not contribute to the maintenance of his illegitimate child. The prosecutrix was Temperance Bouchard[v], a German girl; and it appeared, from her statement, that in September 1864, she was engaged by the defendant as a servant.

Dean at that time kept a lodging house at South Brisbane, The second night after she had been in his service, she allowed an improper intimacy to take place between them, a promise of marriage being made by the defendant. This intimacy was continued afterwards, the same promise being repeated on several occasions.

The prosecutrix accompanied him to Ipswich and also to Rockhampton; at the latter place, both got situations; subsequently they went to Maryborough, where the defendant left her. She was there confined of a child.

On coming to Brisbane, she ascertained that the defendant had been married before she knew him; he refused to have anything to do with the child, and she then obtained a summons.

The defendant did not deny that he had lived on intimate terms with the prosecutrix but denied that he was the father of the child. The Police Magistrate ordered him to pay 7s. 6 d. weekly for twelve months for the maintenance of the child.[vi]

Brisbane Courier, 1866.

Whilst paying maintenance to Temperance for Alfred, Charles’ paternal happiness was further increased when in May 1866, his wife Mary gave birth to their second daughter, Mary Harriet, in Rockhampton. Mary Dean could not have been unaware of the existence of another woman and her baby. If Charles hadn’t told her, no doubt any Rockhamptonite who took the Courier, had.

On 21 October 1866, a baby named John Bouchard,[vii] infant son of Temperance Bouchard, died shortly after admission to the Diamantina Orphanage in Brisbane. This baby was conceived around the time that Temperance was taking Charles to Court over maintenance, and may or may not have been his. Temperance did not put the father’s name on the Orphanage admission book, nor his death certificate. Resorting to placing her child in the Orphanage showed the pressure the teenager felt at having given birth twice in a year, having the paternity of Alfred disputed, and the knowledge that Charles was married, and had fathered another child with his wife.

Desertion – 1867.

Charles Dean now had a wife and two young daughters in Rockhampton, and a mistress and one living child in Brisbane. His marriage to Mary Ann Potts broke down, in what turned out to be a rather public fashion.

Deserting Children. — As the Queensland was hauling off the wharf yesterday, some person drew the attention of Mr. Brown, W.P.M.[viii], to two children who were crying on the riverbank. On enquiry it was ascertained that they belonged to Charley Dean, the Government Chinese Interpreter, who, obedient to a summons, was leaving by the above steamer on business at the Toowoomba District Court sittings.

It appears that before leaving he had a quarrel with his wife and she left the youngsters to him to take care of, vowing she would have nothing more to do with them. In the absence of the police, Mr. Brown had the woman ferreted out during the day, and she was made to take home her offspring and attend to their wants.

This article annoyed Charles to the point of Writing to the Editor, generally something reserved for Europeans who’d had their good name impugned.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE NORTHERN ARGUS.

SIR, Be kind enough to allow me a space in your paper to contradict a statement which referred to me in Wednesday’s Northern Argus, of the 9th of January. It was concerning me leaving my wife and family on the wharf without maintenance, I therefore beg to state that it was not my intention to leave them so. I leave them a house over their head, and also money enough to go on with until my return; but I am in duty bound to appear at the next Toowoomba Assizes, which will take place shortly. I am the Government Chinese Interpreter, and I also sign myself as such. Hoping this short letter will not prove me unjust in the eyes of the public.

I remain yours,

C. DEANE.

Rockhampton, January 22nd, 1867.

One month later, Mary filed a complaint for wife desertion and neglect. Mary claimed that Charles had left her without any support for her or the two girls. She had been treated poorly by him for two years[ix], he had stayed out at night, and made her do all the work at home without a servant (though the last complaint was probably a good thing, given his record with servants).

Charles claimed that she had deserted the children on the wharf when he was going to Toowoomba, that on his return, she had abused him verbally and left then him. He could not, he said, live happily with her, and offered to take care of Annie, the oldest of their two children. The unimpressed Bench ordered him to pay maintenance of 20 shillings per month to his wife for twelve months.

The Dean/Bouchard family 1868.

What exactly happened next to this unhappy couple is not clear. At some point between February 1867 and January 1871, Mary Ann Dean died. A death under the name Mary Ann Dean or Mary Ann Potts in that timeframe does not appear in Queensland records, but Charles was a widower when Temperance finally got him to the altar. Mary Ann Dean had no family in Australia, beyond her husband, so presumably little Annie and Mary were taken care of by their father. (They do not appear in Orphanage records.)

Temperance may have spent some time apart from Charles after the affiliation case, and the ructions in the Dean/Potts union in 1866 and early 1867, but they were back together for the birth of Charles William Dean Bouchard in 1868. In a court case in 1870, Temperance states for the benefit of the court that she lived with Charles in Rockhampton. She was a game young woman, living openly and having children with a Chinese man in the late 1860s. She must have been incredibly relieved when Charles was willing and able to marry her in early 1871.

The make-up of the Bouchard/Dean family was complex. Some of Temperance’s children did not have a father listed on the birth certificate, but it is clear from their names that she considered them to be Charles Dean’s children.

Charles and Temperance also tended to repeat names of their children. When a child (Alfred, Charles) died, they used the Christian name again. From the official records, here are the children of Charles and Mary Ann, Temperance and Charles and Temperance.

Rockhampton, Brisbane, and Warwick – 1870-1878.

Tea? Perhaps?

In March 1868, as reports of Charley Dean’s activities in Rockhampton ceased, the Brisbane Courier reported that a Chinese man named Charles Dean, a merchant in Edward Street, Brisbane, had begun cultivating tea in the Chinese manner. He submitted a sample to the Acclimatisation Society, made from tea plants grown in the Botanical Gardens. The tea he produced and submitted in August that year was a much better sample. It was adjudged that it “would not do discredit to the veritable production of the celestial empire.”[x]

In October 1868, Charles Dean was not collecting his mail at Rockhampton, but the Brisbane Charles Dean[xi] had won an award at the West Maitland Show for his manufactured tea. I like to think it’s the same Charles Dean – how many Chinese merchants with that name can there have been in Queensland in 1868?

Fantan, and a year of trouble – 1870.

1870 found Charles Dean was living in Rockhampton, in Bolsover Street, with Temperance and his children. In a year, he managed to alienate himself from a good proportion of the Chinese people living in that town, starting with informing on gambling dens, and ending with a charge of wounding with intent to do grievous bodily harm.

In February, Government Interpreter Dean made a complaint to the police about a gaming house in William Street Rockhampton, where Fantan[xii] was played for fairly high stakes. Such activity was, of course, illegal.

When the police raided the gaming house, they found about 20 men there. Those who couldn’t escape immediately were arrested, charged and fined. A lot of odd, but valuable, property was found in the possession of Kong Hing, the owner.

“It was further ordered that the money and property found in Kong Hing’s house should be confiscated, and all the gambling materials be destroyed. Half the fines to be paid to the informer. The fines were paid, and the prisoners were released.”

The Rockhampton Bulletin, 1870.

Hmm. Half the fines to go to the informer. That, and the loss of personal property, upset a visiting storekeeper named Ching Foo. He took out an advertisement in the Rockhampton Bulletin, stating that he was merely an observer at the game, and had had his gold rings and a great deal of calico carried off by the police. He accused Charles Dean of paying the fines money towards the fines of all of the players except him. Odd.

Charles Dean, meanwhile, spoke to the Rockhampton Bulletin about the damage “those hells” (gambling dens) did to the lives and families of those who gambled there. He had trouble getting search warrants granted, because of the prevailing attitude that if Chinese people wanted to ruin their lives with opium and gaming, they were entitled (if not encouraged) to go ahead and do so. The Rockhampton Bulletin might have listened, but the Queenslander sneered. Why, there was a house not far from Dean’s own, where dice clinked all day and night. Was the man deaf?

On Monday 18 July 1870, the Rockhampton police attended Charles’ house in Bolsover Street. There they found Dean “scuffling on the floor” with another Chinese man who went by the name of John Peters. John Peters had a lot of blood on his head, and the constables had a lot of difficulty separating the men and getting Peters out of the house.

After Peters was treated by a doctor, who deposed to some nasty wounds on Peters’ head, the court heard two very different accounts of what had happened.

Peters testified that Charles ordered him to come to his house, where Temperance wanted to speak to him. Charles then hit him on the head with a nullah nullah.

Temperance testified that Peters had come to their house, refused to leave, and fought with Charles. She also claimed that the wounds on Peters’ head had been inflicted ten days before by a tomahawk wielded by an acquaintance named Ellen Connolly. After Peters had assaulted her (Ms Connolly’s) mother.

Charles was committed to stand trial at the September 1870 District Court sittings, where Charles asked for time to summon his witnesses. This was granted, and he was released on recognisance to appear at the next sittings.

When those sittings came around the following March, Charles was not called upon to appear, and the case seems to have ended there.

Mr and Mrs Dean of Warwick.

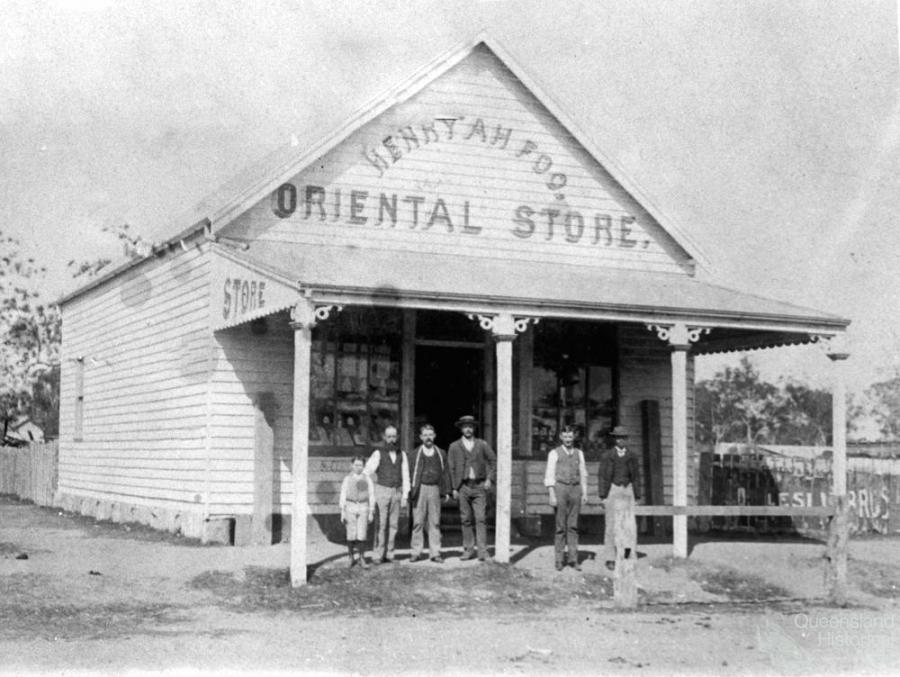

An unnamed merchant on the Downs, and a Chinese business in Goondiwindi – perhaps Charles’ shop and cart were life this. (SLQ).

After spending time in custody in Rockhampton, Charles moved to Brisbane, and married Temperance in January 1871. She was 24, and Charles 32.

The Deans first moved to Ipswich where Charles established a business as a fruiterer, a business he relocated to Warwick by 1873. In 1872, they welcomed, then tragically lost, a little girl named Temperance, and a second Charles passed away shortly after his birth the following year.

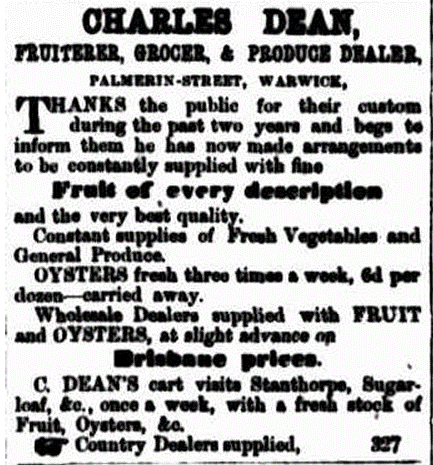

Charles Dean’s business thrived in Warwick. He offered a comprehensive variety of fresh produce, wholesale and retail, and his cart visited towns in the Southern Downs region each week.

When Charles was on the road, Temperance minded home and the store. One day, her children annoyed a neighbour named James P Ross, who came into her house and raised his fist to her, saying “I will muzzle the whole b—-y lot of you.” Temperance denied sending her children out to “annoy” Mr Ross’s children, and ordered him from the house. Fortunately a acquaintance named Mrs Higgins was at her place, and when Mr Ross noticed a witness, he rushed outside. Temperance was so shaken that she froze. Ross was found guilty of assault and fined.

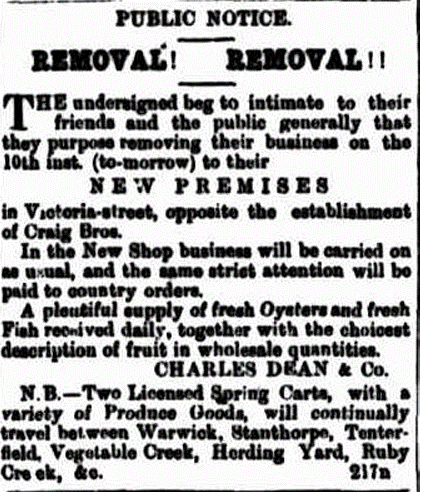

Charles moved his business briefly to South Brisbane, then returned to Warwick, opening a larger store and expanding to two carts visiting Southern Queensland and northern New South Wales.

By 1878, the family seems to have relocated to the Northern Tablelands of New South Wales. Charles gave evidence at Glen Innes in the case of a Chinese man charged with selling opium.

The End of the Adventure.

In 1881, Charles and Temperance welcomed their last child, Alfred Edward Dean in August. A month later, Charles died in Sydney of pneumonia, aged 43.

Many years later, Temperance, a respectable middle-aged widow[xiii], married a man named Frederick De Bor in Sydney (sometimes noted as De Bois or Deabor). The couple seemed to have lived a quiet, comfortable life in the capital of New South Wales until Temperance’s death in 1915 at the age of 69.

She had started life in a crowded silk weaver’s house in the East End, travelled to the other side of the world. She loved, and waited for, a Singapore-born Chinese man. She bore nine children over two decades. She lost her much-loved husband only a decade after marrying him. It doesn’t seem that she ever learned to write, though.

Charles’ daughters from his marriage to Mary Ann Potts married and had families of their own. Temperance was survived by two of her sons, Alfred Edward and Henry.

[i] Huguenots were descended from French Protestants, who had sought refuge from religious persecution. Silk weaving was a particular skill of the Huguenots, and industries sprang up wherever Huguenots settled.

[ii] “The treaty with France in 1860 which allowed French silks to come in duty free, found Great Britain and Ireland unable to compete with France, and in a short time the trade dwindled immensely with disastrous results to Spitalfields and other centres.” British-History.ac.uk

[iii] Records of European immigrants were compiled thoroughly, but the passenger manifests of other ships would simply note “and fifty Chinamen,” or similar, as if they were part of the cargo.

[iv] Kimboo (aka Chimpoo, Chamfoo or Nimpoo, depending on the European who wrote down his name) had a prior conviction for assault, was reported in the press to be suffering from mental illness. Kimboo and was found guilty of Burns’ murder and sentenced to death, but mercy was exercised by the Governor. In 1871, Kimboo murdered a fellow inmate at Brisbane Gaol. He kept in isolation from other prisoners due to his unpredictable behaviour, and eventually died at Woogaroo Asylum in 1893, aged 74.

[v] Here spelled Beauchard. Also, not many German girls are born to French exile families in Bethnal Green.

[vi] The Guardian added to this report: “There were two other young girls outside the Court with babies, of which they alleged Dean was the father.” (If a surviving photo of one of his daughters is anything to go by, Charles was probably a very good-looking man.)

[vii] The Diamantina Orphanage Register spells the surname as “Beauchard.” The length of John’s admission is not recorded.

[viii] Water Police Magistrate.

[ix] In other words, since Temperance Bouchard had been in the picture.

[x] This Mr Charles Dean knew a lot about tea. “In a letter to Mr. Rourke, Mr. Dean says that tea will grow anywhere that is not subject to more than four months’ frost; if the frosts should extend over a longer period, the tree should be planted on land having a north-east aspect and should be protected from the frosts by means of canvass or matting.”

[xi] His name was spelled Dean and Deane in the reports of his tea-making endeavours.

[xii] A guessing/board game involving chance and percentages.

[xiii] In 1884, a baby named Mary Ann Deane was born in New South Wales, and the birth certificate only stated that the mother’s name was “Temperance,” with no surname. No father was listed. That may or may not be this Temperance.