Only he knew how his name really should have been recorded and pronounced. He was best known as Kimboo[i], and all we know of him comes from his interactions with European employers and the courts. He was born in China around 1820. He stood around 5 feet, 2 inches, and was described as neat, pleasant-looking and usually very quiet. He liked to be left alone.

In the late 1840s and early 1850s, British and Chinese labour agencies recruited indentured thousands of labourers to work in Australia. These men were predominantly from the southern provinces of China, and were brought out on contracts of as little as £6 per annum, with two changes of clothes. Conditions at home must have been incredibly difficult for the men to take part in these agreements.[ii]

Kimboo arrived in the colony in 1851, the year that saw the largest number of Chinese newcomers to Queensland before the gold rushes. He worked variously as a labourer and shepherd around Brisbane and the Darling Downs.

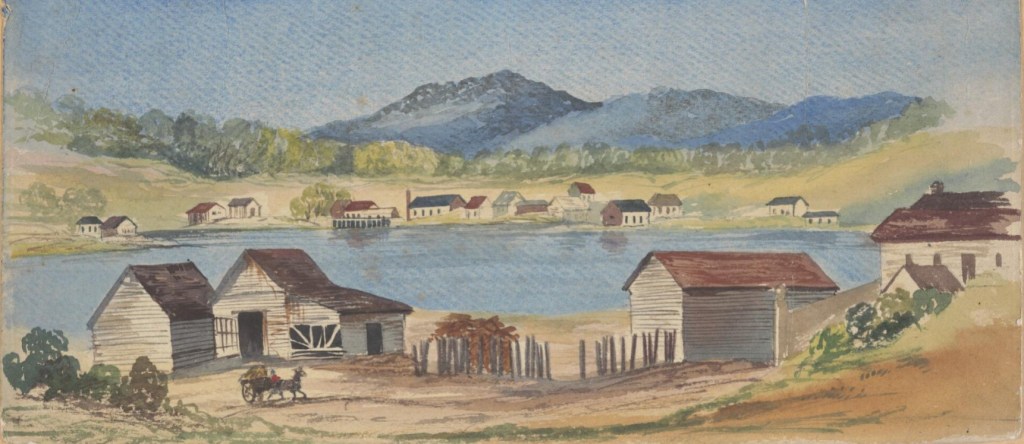

Drayton, 1856.

In February 1856, Kimboo (here called Nienpoo or Nimpoo), was charged at Drayton with assaulting his employer by throwing a stone at him and threatening him. The matter came before the Bench, was considered fully proved, and Kimboo was ordered to keep the peace for six months towards complainant and all her Majesty’s subjects, himself in £50 and two sureties in £25 each.

Naturally, Kimboo, a labourer who could reasonably expect to earn around £10 per annum if his European overseers paid him properly, had no choice but to spend the six months in Brisbane Gaol. His behaviour while in the gaol was described as orderly.

European settlers, accustomed to convicts and ticket-of-leave men working for them, seemed genuinely surprised that their Chinese labourers expected to be paid in full and on time. In silver if possible. Thank you very much. What’s more, these foreign fellows would actually take Englishmen to Court for breaching agreements and failure to pay.

(Apparently, it didn’t occur to the settlers that the Chinese men may have felt that they were performing manual labour for very little reward in a strange country where people spoke an unintelligible language, ate boiled food, and followed peculiar laws and religious practices.)

South Brisbane, 1857.

Exactly a year after his first visit to Brisbane Gaol, Kimboo was residing in South Brisbane. Kimboo’s version of events was that he invited James Orr into his house during a rainstorm, whereupon Mr Orr claimed ownership of the house, and removed some of Kimboo’s property. Kimboo protested, and said he would get a constable. Orr said, “No fear,” and punched Kimboo on his way out of the house. James Orr claimed he didn’t throw Kimboo’s property out, that Kimboo shoved him on his way out the door, and that he slapped Kimboo in reply.

Kimboo (here called Champoo by the Court) summoned Mr Orr, and Mr Orr issued a cross-summons. Kimboo’s interpreter didn’t speak much more English than he did. James Orr had the future Crown Solicitor, Robert Little, acting for him, and had an English-speaking witness. Kimboo’s complaint was dismissed, and he was ordered to keep the peace with a surety of £20 of his own, and two sureties in £10 each.

Again, neither Kimboo nor any of his acquaintances had a year’s salary lying around, and he went back into Brisbane Gaol. His behaviour in gaol was orderly, and he was released in May 1857.

Kimboo went back to his empty house, only to find himself arrested for being illegally on the property. Mr Orr attended Court, eager to confirm that Kimboo had no right to be in that house. Kimboo had trouble making himself understood to the Court, so Samuel Sneyd, the Chief Constable, kindly stepped forward to explain the man’s predicament. The Bench dismissed the case because the property’s owners had not turned up to Court (Mr Orr, it appears, was only verbally authorised to manage it.)

No longer able to live in the house he had leased, Kimboo had few choices. He was arrested a few days later for having no lawful or visible means of support (vagrancy), and given fourteen days in gaol.

It appears that Kimboo went back to labouring on the Darling Downs again. He travelled from station to station, on foot, taking whatever work he could get. Time would tell just how affected he was by the long years of travelling by himself, with his belongings in two sacks attached to a pole that he carried across his shoulders. It must have been lonely, alienating and exhausting.

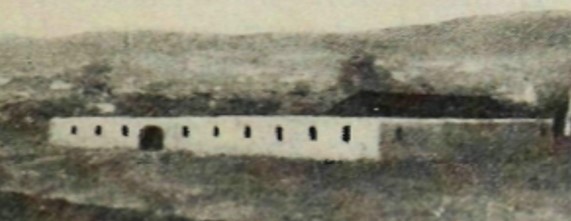

Yandilla Station, 1858.

In March 1858, Kimboo was working as a shepherd/general labourer at Yandilla Station near Toowoomba. The run was owned by St George Gore, who employed Charles Alfred Owen as his station superintendent.

On 8 March, Owen asked Kimboo to take out some sheep, and Kimboo refused. Owen replied that if Kimboo didn’t take the sheep out, he should leave Yandilla station. Kimboo took out a knife and cut Owen in the face, Owen responded by punching him. There followed a fight that went from the kitchen to the yard, where Kimboo got another knife from a pile of blankets, and rushed at Owen, who used a rail to defend himself. Another employee joined in the chase and struggle, which ended with Kimboo captured near a creek bed. Owens discovered that one of his legs was terribly stiff, and realised that he had been stabbed in the thigh.

Owen claimed that he had no previous dispute with Kimboo, although the shepherd had refused the offer of a cheque in lieu of some wages, preferring to be paid in silver. The amount still owed was “about £6 or £7.” In other words, nearly a year’s wages.

Still, inflicting what turned out to be a rather deep and painful wound was an extreme reaction to being owed money. It’s tempting to think that some other provocation might have taken place, although Kimboo’s later violent reactions seemed to have occurred very suddenly. Early reports of the stabbing started to make use of terms like “lunatic Chinaman.”

Brought to trial in Brisbane in May, Kimboo was found guilty of malicious wounding. He was sentenced to two years’ hard labour on the roads.

Prisoners sentenced to labour on the public works of the colony were sent to Sydney, because there was no capacity to supervise them in Brisbane. Kimboo was dispatched to Sydney, where he was processed through Darlinghurst Gaol, and forwarded to Cockatoo Island to serve his two years.

Brisbane Gaol, the former 1820s Female Factory, was crowded, deteriorating, and depressing. Cockatoo Island was worse. Prisoners were fed twice a day, live in reeking, cramped cells and performed heavy manual labour on pain of starvation. Kimboo did his time, and earned a ticket of leave to return to Queensland to look for work on the Downs.

Kimboo had been in Australia for nearly ten years, and had known two living conditions – back-breaking work for subsistence, and prison.

Clifton Station, 1860.

“You may remember some two years and three months ago a diminutive Chinaman being tried for stabbing Mr. Owen, of Yandilla, and sentenced by Mr. Justice Milford to two years imprisonment with hard labour. I was present in the Police Office at Drayton when the preliminary investigation was going on, and it appeared conclusive to me that the Chinaman was mad, and ought to be confined as a lunatic.”

The Drayton correspondent for the Moreton Bay Courier.

On the evening of 24 June 1860, part of a flock of sheep returned to an outstation on the Clifton Station run without their shepherd.

John Heineman waited some time at Ryeford hut for his mate Garrick Burns to come in. When it was clear that Burns was not returning that evening, Heineman rode to the head station and let the overseer, Roderick McLeod, know his mate was missing. McLeod organised a search.

The men searched around the run in the dark, and were about to give up when they heard a dog bark. The dog belonged to Burns, and was found guarding the man’s dead body. Burns had been the victim of a vicious stabbing – he had more than a dozen knife wounds, three of which were described as mortal.

When the police examined the ground near the murder site the following morning, they found signs of a struggle, and a lot of prints of small, bare feet.

Kimboo had been seen on the road about Clifton Station at the time, on his way to Ellengowan with a letter of introduction to the overseer. Kimboo had been travelling barefoot, wearing a pair of corduroy trousers rolled up to the knee, and carried his two swags suspended from a pole across his shoulders.

Kimboo was arrested on suspicion at Drayton on 25 June 1860. On apprehension, he was still barefoot, his trousers were blood-stained, and he had a razor and a butcher’s knife in his possession. Both were stained with blood, and Kimboo had scratches on his face.

While in custody, Kimboo spoke to the Chief Constable Kitching, and made some remarks about a “cranky” Englishman who tried to take his blanket and hit him on the head with a stick. Kimboo apparently told Kitching that in response to being hit on the head, he took his knife and “cut all about the Englishman.”

Kimboo was tried at Brisbane on 21 August 1860 before Justice Lutwyche. He had a competent Chinese interpreter in Charles Deane, and a civic-minded barrister, Mr Jones, watched the case on his behalf. (Kimboo could hardly afford a defence barrister of his own.) He was found guilty of murdering Garrick Burns, and was sentenced to death with a strong recommendation to mercy due to his state of mind.

The death penalty was commuted to life in prison by the Governor. It seemed that Burns had believed that he had been robbed by either Kimboo or another Chinese man, Young, alias “Gentleman John.” When Burns saw Kimboo making his way along the road at Clifton, he told a mate that he would follow the Chinaman and see if he had his property. He had a large stick with him, and grabbed Kimboo’s bundle to search it, hitting Kimboo around the head in the process. Kimboo had reacted by fighting back – with his knife.

Kimboo was put in the new Petrie Terrace Gaol in Brisbane. Once again, Kimboo was “orderly” in custody. The belief that he was mentally ill, raised at the time of the stabbing of Owens in 1858, and generally held by the press at the time of the Burns killing, must have had some foundation.

Perhaps his behaviour, although not disruptive enough to earn the comment “disorderly,” was strange or disturbing to his fellow inmates. Kimboo was discharged to the Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum in August 1865. Dr Canaan examined him and found him to be “quiet and easily managed, worked willingly all the time.” After ten months, Kimboo was returned to the Gaol. It is doubtful that he differentiated much between the two places. He kept to a routine.

Murder at Brisbane Gaol, 1871.

Michael Turley and Kimboo were the only two prisoners in C Ward at Brisbane Gaol on Petrie Terrace. They slept in adjoining cells, but shared the yard of C Ward. Both men had been sentenced to death for murders on sheep stations, and both men had been reprieved because of doubts about their sanity. They had always been on good terms.

By 1871, Michael Turley was a rather feeble man in his seventies, “somewhat eccentric and irascible,” whose only interest or activity was cleaning his cell. The Principal Gaoler didn’t think Turley was fit for any other kind of work, so left him to potter around in peace.

Kimboo, his neighbour, was in his fifties, and spent most of his time “ornamenting his cell with various curious devices.” With the exception of Turley, other prisoners annoyed Kimboo. He liked to be left alone.

Since returning from Woogaroo Asylum in 1866, Kimboo was quiet, and his manner was deemed “inoffensive.” However, in late 1869, Kimboo began exhibiting violent behaviour – becoming angry and destroying his cell furniture. Principal Gaoler Bernard was concerned enough to call in Dr Bell and Dr Hobbs to examine Kimboo, who certified the prisoner to be criminally insane. A move back to Woogaroo had been refused, because the Asylum did not have a secure cell to keep Kimboo in.

In late December 1870, Kimboo was moved to C ward with Turley, after other prisoners in the yard opposite his cell had started to “annoy” him. (One suspects that they taunted the Chinaman on racial and mental health grounds.) Living in C ward next to Turley seemed like a good fit.

On the morning of 25 February 1871, Warder Cox of B and C Wards had gone to breakfast around 7:30 am. No-one relieved him, but there were still guards in the various towers overlooking the gaol. When Cox returned around 8 am, he noticed Kimboo was very agitated, and that Michael Turley was lying down. On his face. With a bloodied broom by his side. He had been bending down when attacked from behind.

Michael Turley lingered for a few hours, before dying of wounds to the back of his head. Dr Hobbs did not think that Kimboo would have hurt Turley “without being provoked.” No-one else gave much thought as to what had led to the attack.

Kimboo was not called to give evidence at the inquest, nor was he charged. After all, he wasn’t going anywhere. The coroner noted that the attack had taken place when a guard had been away without a relieving officer.

The Figaro,1883.

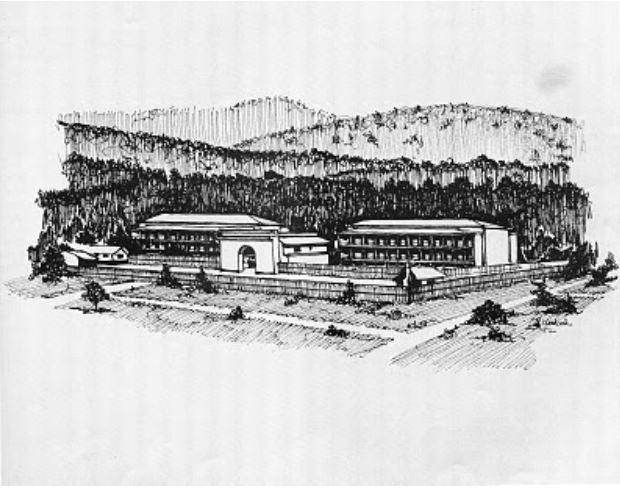

Kimboo is next glimpsed briefly in the pages of the Queensland Figaro, in 1883. Petrie Terrace Gaol was getting ready to close for the move to the new gaol at South Brisbane.

The Figaro’s reporter noted that Kimboo was at the head of the indulgence list, along with Kelah, a South Sea Islander who was also doing life. Kimboo was described as an unusually clean and inoffensive looking man, who had an exercise yard to himself “because he is dangerous when annoyed.” And the new breed of criminal – the larrikin – now infesting Brisbane Gaol would annoy him deeply if given the chance.

Woogaroo, 1885-1893.

Kimboo was in his late sixties when he was readmitted to Woogaroo. The Asylum hadn’t been able to accommodate Kimboo in a cell at the time he murdered Michael Turley, but it was able to take in an elderly man beginning to lose his faculties.

Kimboo grew withdrawn and silent over the years, until an infection laid him low in February 1893. Kimboo entered the hospital ward at Woogaroo. His abscess cleared up, but he did not recover his health properly, and developed swelling of his limbs, leading to his death from a lumbar abscess on May 8 1893. He was buried in the cemetery at the Asylum.

And that’s what we know of a man who came to Queensland seeking a living, but found discrimination, poverty, hard work, insanity, and prison.

[i] He was also recorded as Kim alias Champoo, Nimpoo, Kim Poo, Niempoo and Chimpoo.

[ii] The Australian National Museum notes increasing population in the Guangdong and Fujian provinces, as well as invasions, rebellions, famine and severe weather events in China generally in the mid-19th century as drivers of Chinese labour immigration to Australia.