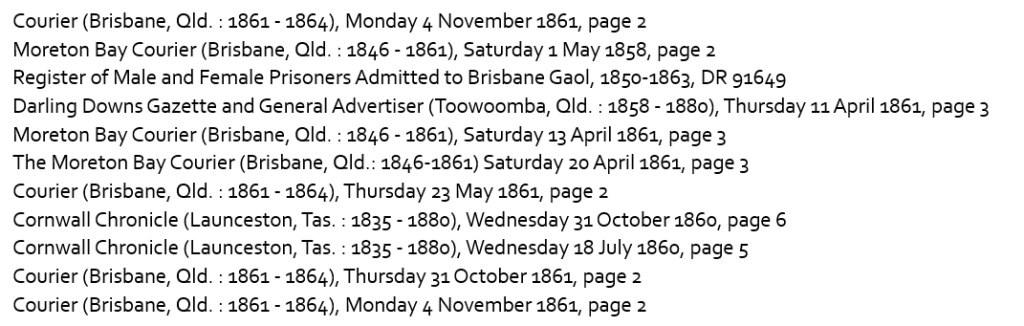

Reading the 1846 article, “Love in the Bush,” made me think of that grand old 19th century tradition – elopement. Was it common in Queensland?

A survey of the papers revealed that elopement in that century was a portmanteau term – it could mean a flight to the altar against parental wishes, a cheating spouse leaving with another partner, or simply the act of leaving a location without notice. Usually without settling the bill, too.

In Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom, elopements in the high life were occurring on an industrial scale. It seemed that no stately home in England was complete without a ladder leaning against the youngest daughter’s window. Footmen seemed to be a popular choice for ardent young ladies who longed for an escape from the tyrannies of Papa and the prospect of a future spent with a chinless wonder plucked from the less-visited pages of Burke’s.

In Queensland, elopements of the traditional variety – young ladies running away with unsuitable men – were quite rare. Put-upon wives leaving their husbands for another man was much more common. The men they fled with usually appropriated a good deal of the husband’s property as well as their lawfully wedded wife.

But, after the bucolic romance of the shoemaker and the sheep-station belle, it was more than a decade before another elopement made news.

Stealing A Wife and Bedding.

Michael McLennan insisted that his marriage had been happy, although his wife, Ellen, “seemed always to be in very bad health.” The McLennans operated a boarding house in Ipswich, and in early 1858, a new chum from the old country, Michael Ryan, stayed in their premises.

On February 11, McLennan saw Ryan at breakfast, shook his hand, and bade him good day. Later that day, McLennan returned home to find his kitchen not occupied by his wife. Odd. He went to the bedroom to get some tobacco, and noticed that his wife’s clothing was gone. He also noticed that the mattress in Ryan’s room was gone. McLennan checked his linen cupboard. He found himself missing four sheets, one blanket, one pillow slip, a pair of socks, a towel, a prayer book and the counterpane from his bed. And Mrs McLennan of course. He later discovered that she had placed her wedding ring in one of his boots.

Another boarder at McLennan’s, John Kerr, had helped Ryan load a dray for a journey to Jimbour. There were some rather heavy goods in bundles, but they were tied up in sheets. He didn’t see Mrs McLennan about the dray when it was loaded up.

The dray had been hired from Joseph Reece, who met Michael Ryan and a woman he introduced as Mrs Ryan. At a campsite on the way to Jimbour, the couple had slept on the mattress under the dray.

Constable Devine located the couple, the dray, and the lost bedding. Mr McLennan was pleased to be reunited with his property, but not his wife.

When the matter came to court, Mrs McLennan took all the blame for removing her husband’s goods, and putting them in the dray. Ryan, she insisted, had refused to take McLennan’s things. Ellen further claimed that she had instigated the elopement, by threatening to “make some bad end of myself, drown myself or something,” if he would not take her away. McLennan had beaten her at Christmas time, and she would not stay with him.

The jury was instructed that a wife could not steal the goods of the husband, but if she eloped and gave the goods to the adulterer, that man was guilty of a felony. Michael Ryan was found guilty of stealing the property of Michael McLennan, and was sentenced to a year in Brisbane Gaol.

The adulterer dealt with; the judge ordered that Ellen McLennan be brought into court. Mr Ratcliffe Pring, for the Crown, submitted that there were not enough witnesses to sustain a charge of perjury against her. “He hoped she would go away and do better for the future.” The judge reprimanded her for her conduct and discharged her.

One hopes that “doing better” did not involve returning to a husband who had beaten her, and who valued his missing bedding more than his wife.

Elopement(s) Extraordinary.

1861 was a bumper year for elopements. In April, two elopements shocked Toowoomba. The first involved three prisoners overpowering the wife of the local lock-up keeper, and escaping. (The gaoler was away at the time, tasked with taking the census.)

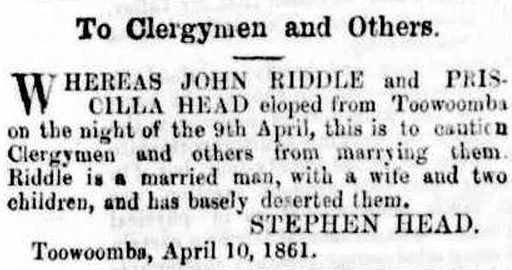

The second elopement occupied the papers of Brisbane and the Darling Downs for nearly a month. A “blooming damsel of sixteen,” Priscilla Head, absconded from her hired service with the Seale family. A married man in his forties named John Riddle disappeared at the same time. Mr Riddle’s wife, who was expecting their third child, was devastated.

The mailman happened across the delinquent couple on the Ipswich Road, and learned that were headed for Sydney. When the postie arrived at Toowoomba, his tale of meeting a certain young miss and her much older mister scandalised the town.

“It is shocking to contemplate a transaction of this kind, and it is evident proof of the deep villainy of the principal delinquent when I state that he made away with everything available for money, and he has left his poor wife and family miserably destitute.”

Moreton Bay Courier.

Priscilla’s highly respectable father, Stephen Head, took out an advertisement, warning clergymen against marrying the pair.

The police caught up with the pair in Brisbane ten days after they fled, and charged Mr Riddle with deserting his wife and family, and Priscilla Head with absconding from service. Priscilla, the press noted, was “a well-dressed and prepossessing young woman.” After a further day or so of sensation, the charges against both were dismissed for want of evidence. No-one thought about charging Mr Riddle over his activities with an underage girl, just as no-one thought about protecting her identity.

It’s not hard to imagine the difficult conversations and sideways looks that greeted the parties when they returned home.

Another elopement that ended unhappily was that of Henry Wells and Mrs Spearman. This elopement began in Tasmania and ended in Brisbane.

Wells had been a coach driver for Mrs Spearman’s publican husband in Deloraine, Tasmania.[i] He was a man of mature years, who had a wife and children, and was well-liked in the district.

Passion must have simmered away quietly in the background at Spearman’s Coaches, because in late 1860, Henry Wells and Mrs Spearman suddenly left their families and fled to the mainland. Mr Spearman was having none of that. He pursued the fugitive lovers through the colonies of Victoria and New South Wales.

In Sydney, Harry Wells was arrested on suspicion of desertion, and promptly jumped his bail. The runaway middle-aged lovers fetched up in Brisbane, and opened a boarding house in Charlotte Street. Imaginatively, Wells had an alias. Smith.

A few months after arriving, Henry Wells came down with a persistent cold. He worried about being arrested by a detective who had been sent to check for his whereabouts in Rockhampton. He told friends that he was deeply upset about the disgrace his actions had brought on his children, and on Mrs Spearman. These worries pressed on him, and his cold worsened.

On Tuesday 21 May 1861, Harry Wells collapsed on his sofa and died. Dr Cannan conducted a post-mortem that indicated heart disease. The verdict of the coroner’s jury was that he died from disease of the heart accelerated by nervous excitement.

1861 had one more elopement story for Queensland. In late October, Frederick Lawrence was doing his usual rounds in Brisbane Town, pushing a handcart about, and selling ginger beer. When he returned home from relieving the parched throats of Fortitude Valley, he discovered that he was missing (a) Mrs Lawrence, (b) a boarder named Frank, and (c) the better part of his personal wardrobe. (The losses included £63 cash, most of his best clothing, a silver watch and Maria Lawrence.)

Mr Lawrence went to the police station to take out a warrant, but Maria and her paramour, “known to his circle of acquaintance by the euphonious title of ‘Frank the Slasher’,” had already left Brisbane on the steamer Clarence. Really, Maria? Frank the Slasher? Perhaps married life had hitherto been dull.

The coming decade would provide more in the way of elopement – including a shooting of a scoundrel by a vengeful papa, a famous divorce, and a young man who risked it all for the love of his – stepmother? That will be another post entirely.

[i] 1860 had been a rough year for Henry Wells – his coach had run over and killed a child (although the father of the child did not place any blame on Wells), and he had been the subject of the 19th century equivalent of a police sting for speeding. Constables Gould and Williams concealed themselves in bushes near a hill, and watched the coach go by to try and guess its speed. They decided that the vehicle had been flying along at a high speed, whereas passers-by and the passengers of the coach thought it was going at a gentle canter.

Apart from the sketch of Brisbane in 1860 (which is from the National Library of Australia), and the newspaper clipping, all images are AI generated.