Prisoner No. 36.

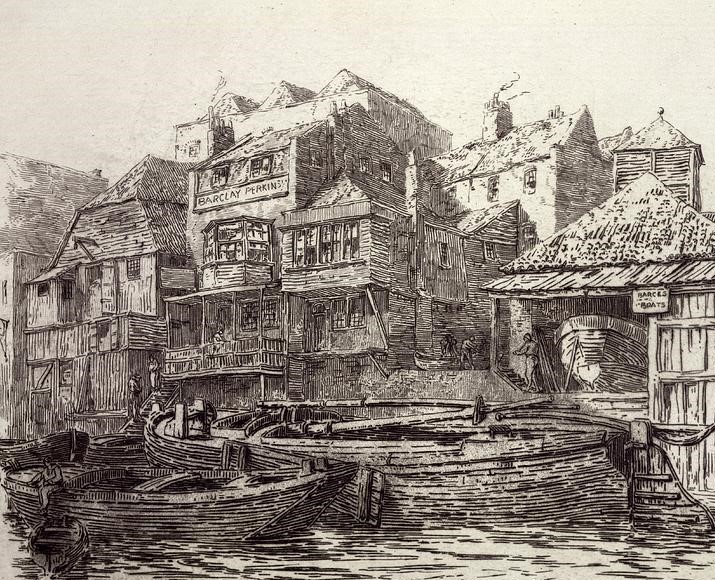

Bristol and Shadwell.

James Turner was destined for a life on the water – he was born in the harbour town of Bristol around 1799. At the age of nineteen, he stood nearly five feet six inches, had light brown hair and blue eyes. He had tattoos on his right arm – the figures of a man and a woman, and his initials, “JT.”

In 1818, Turner fetched up in the East End maritime hub, Shadwell. It was there that Turner and his mate James Perkins were observed to help themselves to eight yards of cotton that Samuel Haskins had, for reasons best known to himself, hung outside his dwelling.

Haskins’ keen-eyed neighbour testified at the Old Bailey that “Perkins took the cotton off the prosecutor’s iron rail, and put it under Turner’s smock-frock – They went away together.”

The teenagers claimed to know nothing about it, but were found guilty and sentenced to transportation on 9 September 1818.

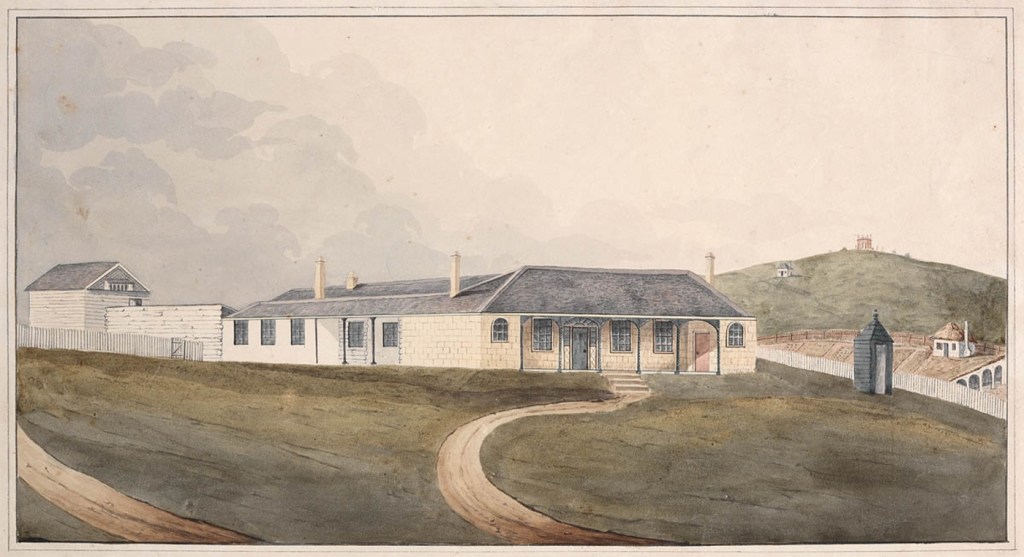

Hobart Town – 1820.

James Turner was transported to Sydney on the Prince Regent, arriving on 27 January 1820, and was then transferred to Hobart Town on the Castle Forbes. The second journey would have been an interesting one – one of his shipmates was Alexander Pearce, whose stay in Van Diemen’s Land was punctuated by escapes, thefts, murder and cannibalism.

James Turner landed in Hobart Town on 4 March 1820, and was put to service as a ferryman at Kangaroo Point. He worked his service without incident until late December 1820, when a female servant named Catherine McGinnis boarded his ferry. There were no other passengers on board, and Turner raped her. At the trial in January 1821, Turner claimed that she had consented to intercourse in return for a pair of gold earrings, and when she didn’t get them, pressed the charge. (I find it somewhat unlikely that a convict ferryman would have a pair of gold earrings at the ready to entice a stranger into a sexual encounter. Or that a young woman would be willing to surrender to a convict ferryman on the doubtful promise of same.)

Turner was found guilty, and sentenced to life (commuted from death). That commutation was directed to take the form transportation to Newcastle, which occurred via the Midas the following day. The machinery of government doesn’t usually move so swiftly. The Midas would have been ready to sail that day regardless, but there was a certain speed to the arrangements that suggests the authorities at Hobart Town were eager to be rid of Turner. A brief stopover in Sydney Town to board the Elizabeth Henrietta, and he was on his way to Newcastle.

Newcastle to Port Macquarie to Moreton Bay.

James Turner spent nearly three years at Newcastle Penal Settlement. Convicts were employed there in building projects, coal mining, cedar felling and lime burning. When the Newcastle settlement was closed in late 1823[i], Turner was one of the 900 remaining convicts transported on to Port Macquarie.

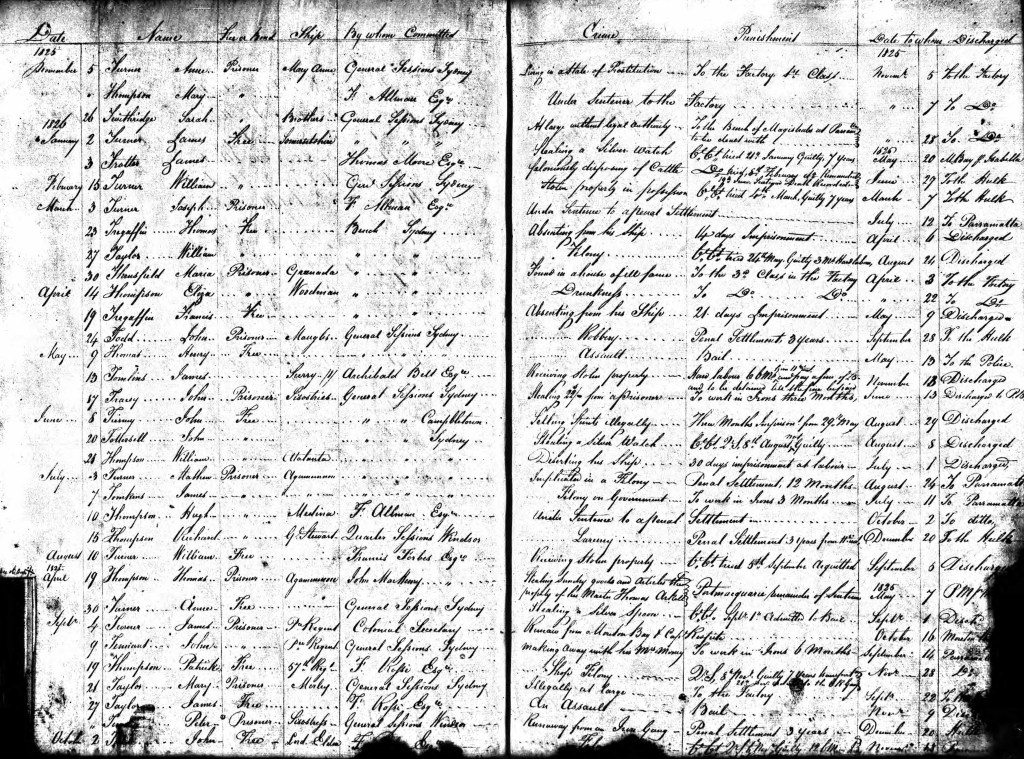

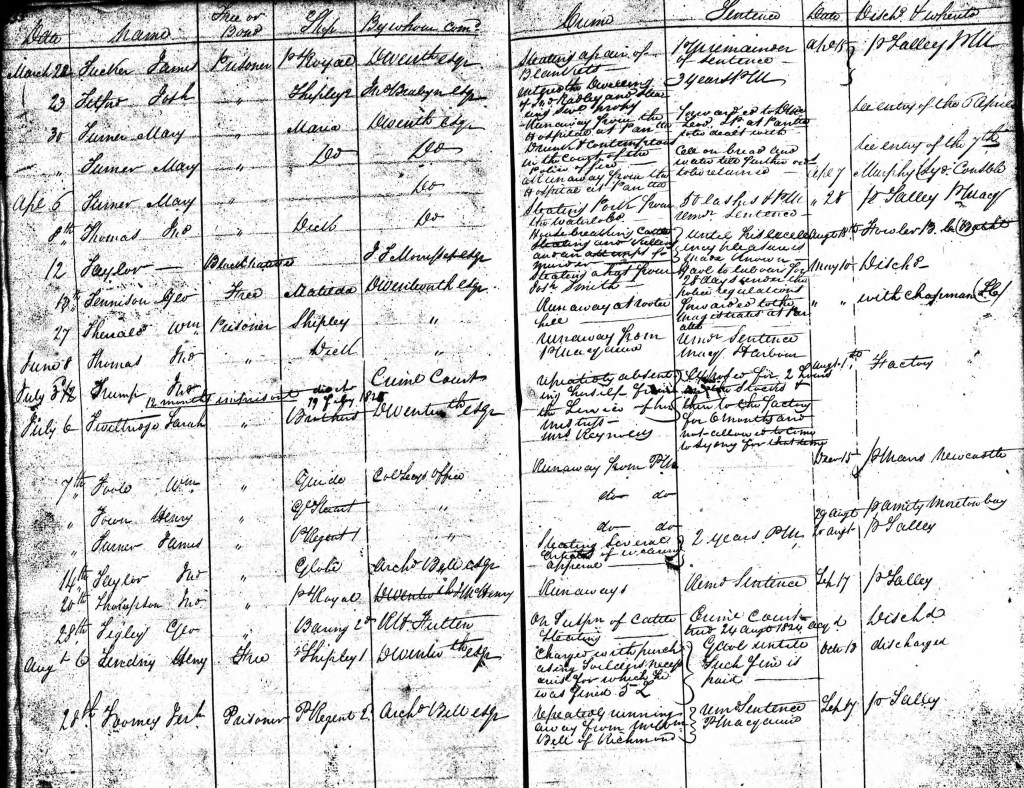

Port Macquarie was opened in 1821, to punish and work for “the worst description of convicts,” and appears not to have suited James Turner at all. He was one of a group of twelve prisoners who absconded in 1824, and Darcy Wentworth saw fit to send them, not back to Port Macquarie, but to Macquarie Harbour, Van Diemen’s Land, for the residue of their sentences. That was on July 9 1824. In August, His Excellency the Governor was pleased to alter the orders in the case of James Turner, and direct that he go to Moreton Bay per the Amity.

Turner was in a different position to many of the other Amity prisoners – he was not a volunteer, nor was his Colonial sentence short. Even when his original sentence expired, his capital conviction in Tasmania meant that he had little hope of leaving the place until middle age.

He endured the initial setting up at Redcliffe, with its shortage of fresh water, no shortage of sandflies, and the unfriendly response of the local indigenous people to the first group of white people who wouldn’t go away. Every other ship bearing white people had gone away. This lot set up buildings and seemed inclined to stay there. Until one happy day, the Europeans packed up and headed down the river to the inland.

On 12 January 1826, a group of prisoners legged it from Moreton Bay. They included James Turner, Charles Penny, Lewis Lazarus, William Hartland (Hartlin), John Newman and William Pittman. They made their way down to Port Macquarie, following in the wake of the October 1825 runaways.

“The accounts which have been just received from Moreton Bay, are by no means satisfactory. Very little progress has been made during the last two or three months, either in cultivation or in erecting buildings. This state of things is occasioned by the indolence of the prisoners, and the difficulty that there is of making them work.

They have discovered a road to Port Macquarie; and, they are continually running away. The distance between this place and Moreton Bay is not less than five hundred miles; yet, they seem to prefer encountering all the hardships of such a journey, with all the consequences of flogging, &c. than settle to their employment.”

The Australian, March 1826.

Return to Moreton Bay

James Turner was forwarded from Port Macquarie to Sydney Gaol, and was returned to Moreton Bay on 4 November 1826. In 1828, he appeared before Captain Logan and received 50 lashes, and made one more escape, being out for nearly four months in 1830.[ii] After that, his behaviour was viewed as steady and useful.

Skirmish with indigenous people.

From the Commandants’ reports to the Colonial Secretary, we learn that James Turner had been severely wounded by indigenous people while working to recover runaway convicts, some time between 1831 and 1833. He was mentioned as being involved in this incident:

“Again, during 1832 Chief Constable James McIntosh and a convict trustee named James Turner, out chasing runaways, were severely injured by Aborigines near the Cabbage Tree Creek estuary and only rescued by the arrival of a larger party of whites.”

Raymond Evans.

One of the sources for this account is found in a letter to the Moreton Bay Courier in January 1847, in which a writer calling themselves “Anti-Humbug” outlined a series of actions against Europeans allegedly taken by a recently-murdered indigenous man known as Millbong Jemmy.

“In 1832, he, with several others, attacked two men belonging to a boat’s crew, and after beating them severely, proceeded to roast them on the fire. The return of the Commandant and the remainder of the crew fortunately saved the lives of the men, but they were both in the Hospital for nearly twelve months, and never fully recovered.”

In a letter to the Colonial Secretary in 1833, Commandant Clunie mentions an attack by Dunwich Tribe “sometime ago” in which one convict and two soldiers were injured.[iii] The men were saved by the arrival of a group of soldiers who had just landed at Dunwich.

James Turner would spend a long time in Moreton Bay Hospital in 1833, and he may or may not have been the convict injured at Dunwich on that occasion.

Petitions and Injuries -1833.

Twelve years had passed since James Turner was convicted and sentenced to penal servitude for life in Hobart Town. His original sentence had expired, and he felt that it was time to petition the Governor for commutation of his colonial sentence. He gave a largely accurate account of his career since 1821, although he seems to have forgotten two other instances of absconding.

25 January 1833

His Excellency –

Major General Richard Bourke

Governor in Chief &c., &c., &c.

The Humble Petition of James Turner a Prisoner of the Crown at Moreton By Most respectfully sheweth,

That your Petitioner arrived at Hobart Town Van Diemen’s Land per Ship “Prince Regent” in 1819, under sentence for seven years.

That your Petitioner in an unguarded moment and in a state of intoxication committed an assault upon a Female for which offence he received at the Criminal Court Held in Hobart Town January 1821 “Life,” and shortly afterwards was forwarded to Newcastle, where he remained upwards of Three Years without the slightest misconduct alleged against his character.

That your Petitioner on the abandonment of the Settlement of Newcastle was drafted with others to Port Macquarie where he remained until this Settlement was also abandoned.[iv] Your Petitioner was then forwarded to Moreton Bay where he arrived in 1826,[v] but in consequence of the hopeless sentence under which he laboured and being so frequently transferred to different Penal Settlements, was imprudently induced to abscond, since which time he has continued to behave himself to the satisfaction of his superiors, and has not during that long period been punished for misconduct,[vi] in information of which statement he most humbly begs to refer to the Civil Authorities with whom he has been placed.

That your Petitioner must humbly prays, that your Excellency will take into your humane consideration his long course of good behaviour except in the solitary instance of his absconding, and allow him a commutation of sentence according to the Regulations laid down for Prisoners, labouring under sentence for Life, having served 12 years of his Colonial Sentence in January 1833 and your Petitioner will ever Pray &c.

James Turner

Moreton Bay 14 January 1833

Turner was one of six prisoners who petitioned His Excellency in January 1833. His Excellency’s response was curt.

“They have not qualified themselves by length of servitude for indulgence under the regulations.”

By the time the response arrived at Moreton Bay, James Turner would be in hospital.

On 18 February 1833, two injured convicts were admitted to the Moreton Bay Hospital. Patrick Byrne was suffering from vulnus,[vii] and James Turner had vulna et fractura.[viii] Patrick Byrne was released after a week, and was able to return to Sydney as scheduled at the end of the month. James Turner would not be well enough to be released for two months.

Just how severe Turner’s injuries were is revealed in letters from Captain Clunie and Assistant Surgeon Murray nearly eighteen months afterwards. The men recommended that James Turner (and an elderly man named Thomas Treslove) be forwarded to the Invalid Depot at Port Macquarie, as they were unfit for any kind of labour. Clunie added that, “Turner’s conduct has been extremely good while here, and that some years ago, while employed in a boat in pursuit of runaways, he suffered severely from an attack of the natives.”

The reply took up one sentence:

“I am directed by the Governor to acquaint you that these men are to remain at Moreton Bay, but not to be put to Labour.”

It may be in this case that the skirmish with the indigenous people took place in February 1833. Or that Turner was injured in some other way in the course of his work at Moreton Bay. From Turner’s description later in life, he had suffered a fractured right kneecap, along with other wounds.

James Turner steadily recovered his strength over the next few years, to the extent that he was back working in the pilot boat crews in 1837.

Northern Expeditions – 1837

In May 1837, Major Sydney Cotton took two whale boats north to Wide Bay to search for a vessel reported to have run aground with women and children on board. Samuel Derrington acted as an interpreter, and James Turner was on the boat crew. The search party found no evidence of a vessel having come to grief. On his return to Moreton Bay, Cotton reported favourably of the exertions of the men under his command.

Not long after this, the Duke of York was wrecked near Noosa (Huon Mundy), and two crewmen were reported missing. Lieutenant Russell and two boats went north to find out what had occurred, with James Turner again part of the crew. Lt. Russell reported that the local indigenous people were not well-disposed to Europeans, and after much commentary on that topic, reported that the missing men had been killed.

The Governor noted that, “Derrington, John Walsh or Gallagher, Webster, Lloyd and Turner who were engaged in two services with this should have their former rewards doubled and if any should be convicts for life their sentences will thus be reduced to seven years.”

In June 1838, Major Sydney Cotton wrote to the Governor, with a list of prisoners eligible under a new Act for conditional remissions of their sentences (including James Turner). The Colonial Secretary replied that he needed a list of the convicts and the “full particulars of their respective cases,” before doing anything.

Not long afterwards, the Command at Moreton Bay changed again, and Lieutenant Owen Gorman was appointed. His task was to oversee the dismantling of the settlement in readiness for its eventual closure. Gorman noted Turner’s presence on the pilot boat crew in 1839 – as coxswain and overseer.

Sydney Town – 1840.

As 1840 began, James Turner’s sentence was set to expire. It was seven years since his petition, and various Commandants had recommended him for remissions from the Governor during those years. He was seen as a hardworking and steady man, who had made himself useful in the boat’s crew, and had survived severe injuries from a conflict with the indigenous people. And still, it seemed that the Government was reluctant to act.

Lieutenant Gorman forced the hand of the authorities in Sydney Town. He sent James Turner and William White with the mail to Sydney, and then wrote to the Colonial Secretary for instructions. He mentioned that their sentences were about to expire, and recommended both be granted tickets of leave.

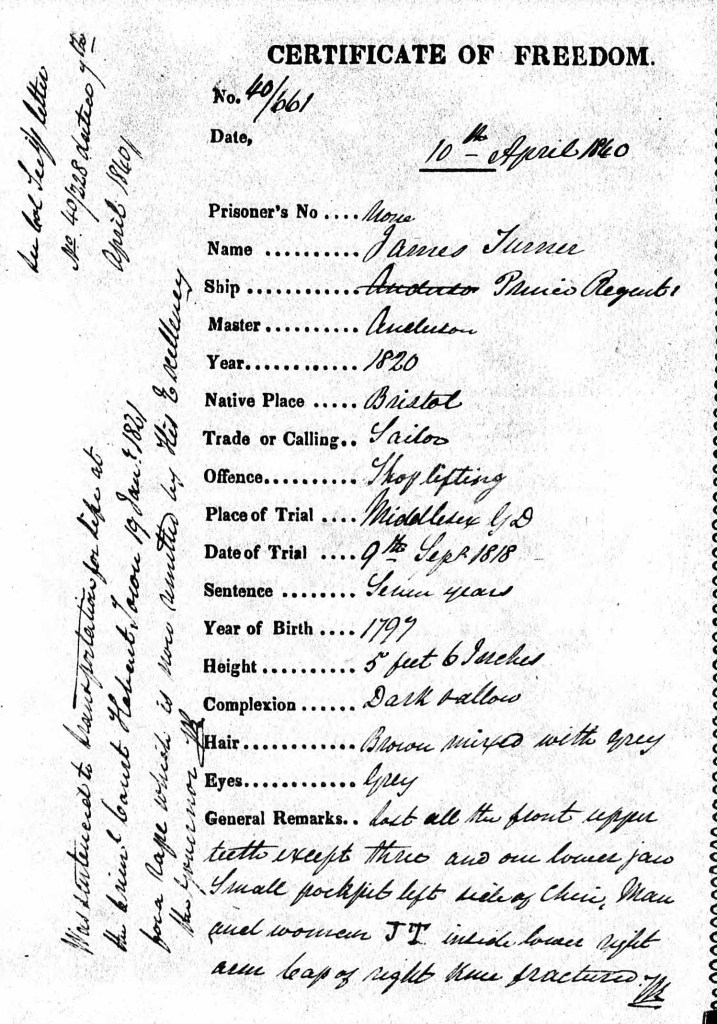

After a lot of marginal notes and referrals back and forth in Sydney, the Principal Superintendent of Convicts was instructed to take their physical descriptions and prepare free pardons for their Colonial offences. And thus, both men were granted Certificates of Freedom. In his 22 years in custody, James Turner had lost all but four of his teeth, had gone grey, and had a broken kneecap (and no doubt a pronounced limp). He was 41 years old.

[i] There were too many valuable natural resources at Newcastle to justify its remaining a convict settlement.

[ii] He was recorded as having run on 18 January 1830 and returned on 02 May 1830 in the Chronological Register, but in the Book of Monthly Returns for that time, his return was not recorded.

[iii] Clunie was describing relations with indigenous people since the murder of Captain Logan in 1830, and reported good relations with all groups, except those at Dunwich.

[iv] Turner is in error here – the Port Macquarie Convict Settlement did not close until November 1828. He absconded from Port Macquarie in 1824.

[v] Turner arrived at Moreton Bay on the Amity in 1824, after spending some time in Sydney Gaol for absconding from Port Macquarie. He was returned to Moreton Bay after absconding in 1826.

[vi] Spicer’s Diary records a corporal punishment inflicted in 1828, and a further absconding in 1830.

[vii] Wound or injury.

[viii] Wounds and a fracture or broken bone.