This rhetorical question asked by King Henry II was taken literally by some of his more brutish knights, who proceeded to Canterbury to take the life of Archbishop Thomas à Becket.

Moreton Bay Commandant Patrick Logan must have mused on that statement in 1829, when the Church of England decided to extend its chaplaincy to his convict station, and thought that the ideal person for the job would be the Reverend John Vincent.

A Chaplain to the Convicts

The Elizabeth. 1827-1828.

The Reverend John Vincent was approaching 40 years of age when he ventured from Cork to the Colony of New South Wales in 1827, putting aside the comforts and familiarity of home in the service of his Lord. His wife Eliza and their four young daughters bravely undertook the long voyage with him on board the convict ship, Elizabeth.

It would be a very trying voyage for everyone concerned. The convicts – all female – were described as “the worst and most troublesome” who had ever embarked at Cork.[i] 194 female convicts were embarked on 6 July 1827, 192 would arrive at Botany Bay.[ii]

Rev. John Vincent noticed a lot of irregularities on the voyage. The convicts mixed in with the crew too freely, a prisoner had jumped overboard, and he suffered a lot of mockery and abuse from the convict women, something not prevented by those meant to be in charge .

After five months of hell on the high seas, the Elizabeth arrived in Sydney Town in January 1828. Vincent was moved to lay formal complaints against Surgeon Joseph Hughes and the ship’s Master, Walter Cock. These included improper intercourse between the convicts and crew, the suicide, and (one suspects, most importantly of all) “the disrespectful treatment that the Rev. Vincent and his family were subjected to.”

Rev. Vincent would have to wait for the machinery of two Governments, half a world apart, to deal with his complaints about his voyage to New South Wales.

A Passage to Moreton Bay. 1828-1829.

Very little would go smoothly on the road to his first appointment in Australia. His chaplaincy at Moreton Bay was publicly mooted in January 1828, but he would not be formally gazetted in that position until September 1828, due to his growing reluctance to take up the post. In the interim, he acclimatised himself to life in the Colonies as an assistant to the Rev. Mr Samuel Marsden at Parramatta. Vincent claimed to find these duties exhausting, presumably in hope that the Archdeacon might find him too ill to go to Moreton Bay. If anything, Archdeacon Scott only became more determined.

Getting the new chaplain to Moreton Bay would tax the Church of England, the Master Attendant’s Office and the Colonial Secretary for several months. The Vincents had, since arriving in New South Wales, been blessed with a son, and another was on the way. He had a servant man, three female servants, and his belongings. He sought to bring along some sheep, pigs and poultry for the family’s use. The Archdeacon hoped that the Colonial Secretary could arrange same in September 1828.

The Colonial Secretary desired that the Master Attendant at Sydney book Vincent on the first passage to Moreton Bay. The Master Attendant begged to acquaint the Colonial Secretary that there were 30 tons of provisions and stores to be shipped on the next vessel, and that half the bread and flour would have to be left behind to provide the necessary space.

When the Governor insisted, the Master Attendant advised that there were now between 200 and 300 prisoners ready to be shipped to Moreton Bay. There were a lot of commercial vessels lying in the Harbour – could they perhaps call for tenders to get Vincent to the Bay? His Excellency made a gruff note permitting this, the Colonial Secretary contacted the Commissary-General, and tenders were called in December 1828.

Finally, on 27 March 1829, the first clergyman at Moreton Bay was deposited in Brisbane Town.

At first, Commandant Logan didn’t seem overly interested in the new arrival, and in May merely noted Vincent’s request for convicts to be assigned as Clerk, Sexton and Bell Ringer. He told the chaplain that he’d get back to him.

We need a Church. I’m a Chaplain after all.

The Reverend Vincent made himself very busy checking the state of the settlement, and found it in many ways lacking. He decided that he was the man to sort this out, and he wrote to the Archdeacon with his observations. There was no church; and conducting services for 700 prisoners in the Barracks was uncomfortable and unsuitable for the families of Officers. The Parsonage was too small for select, officers-only services. He had no sexton, clerk or gravedigger. The schoolroom was snug and rather too close to the wharf, and the burial ground was unenclosed, distant and small. The Archdeacon passed Vincent’s suggestions along to His Excellency, although he didn’t feel that he was qualified to comment on distant graveyard locations.

Six weeks after his letter simply brimming with ideas, Vincent’s tone became peevish. He complained of the unfinished state of the Parsonage – convict labour was often diverted by the Commandant to other works. Vincent knew that while the Parsonage remained unfinished, it was the property of the Government, and under the control of one Patrick Logan. Only when the work was complete could control be handed over to the Church.

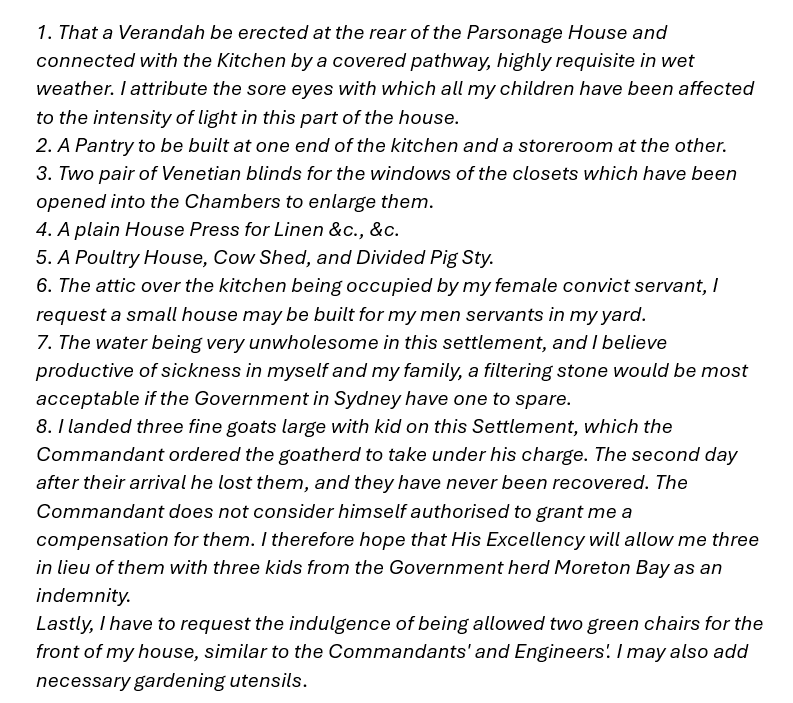

Rather than approach the stiff-necked Commandant, Reverend Vincent approached the Sydney authorities directly, creating an atmosphere of mistrust between the men. Vincent attached a list of needs to his Colonial Secretary letter:

Governor Darling scrawled on the letter: “Refer him to the Commandant, through whom all his applications to the Govt ought to pass.”

It was around this time that Commandant Logan was made aware of just how often the Chaplain was going over his head to Church and Government officials in Sydney (contrary to the instructions Vincent had been given before arrival).

On 7 September 1829, Reverend Vincent wrote to Scott, asking for an update on the inquiry into the voyage of the Elizabeth, nearly two years earlier. The response, when it came, would hardly have pleased him.[iii] Three days later, the Reverend had rather more to worry about.

The Unfortunate Deceased.

Michael Collins had been a free man less than six months earlier. He’d done his seven years’ transportation to New South Wales for stealing a pocketbook and some bank notes in 1814, when he was a teenager. He’d earned a Certificate of Freedom in 1824, and had mislaid it a couple of times. He spent time in the Lunatic Asylum in 1825, then found work there after his condition improved.

In May 1829, Collins stole some clothes and money from the hut of Mr Sparke, and was sentenced to seven years’ transportation to Moreton Bay. If he was honest with himself, he’d admit to having a spot of bother before, but not convicted of anything. If he’d been around today, he’d be described as having some mental health issues, but in 1829, he was described as a lunatic or a vagabond. He just didn’t fit in.

Collins arrived in Moreton Bay on the Waterloo at the end of August 1829, and was assigned to the work on the newly completed treadmill. Within the fortnight, he was dead.

10 September 1829

On 10 September 1829, Reverend John Vincent was finishing the burial service of a convict (probably George Bull[iv]), when he was told that a convict had just lost his life on the treadmill at the Windmill overlooking the settlement.

He rushed to the convict hospital, and discovered that 32-year-old Michael Collins had died on arrival. The poor man had become entangled in the machinery, and had suffered catastrophic head injuries.

Reverend Vincent went back to the parsonage, and waited for someone to bring him a Funeral Report, and for an Inquest to be convened. And waited. (Captain Logan was at the Bay, discharging the Waterloo, and Lieutenant Thomas Bainbrigge acted in his stead.)

11 September 1829

The following morning, a convict named Daniel Brown was dispatched by Overseer Ross to ask Reverend Vincent for orders to toll the bell, and for his surplice to conduct the burial of Collins’ body. That wouldn’t do at all, thought Vincent, and he refused to conduct the burial until he had a report or warrant. He took up his pen.

Bainbrigge wrote to Vincent, advising that he did not know about the verbal message. He did not feel authorised to call a Jury, but was taking statements from witnesses. Captain Logan would be back tonight, and Dr Cowper had said that the corpse “would keep” another day until the proper arrangements could be made.

12 September 1829

On Saturday, Dr Cowper told Bainbrigge that Collins needed to be interred as soon as possible, and Bainbrigge wrote to Vincent with this information.

Vincent replied, “I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of this morning’s date and beg to acquaint you that an official Funeral report must be furnished, previous to the discharge of my ministerial duties.” He followed up with a note, asking if Bainbrigge declined sending or ordering a report.

Captain Logan arrived back at the Settlement later that morning, and noticed a funeral procession leaving the Hospital, with no Reverend Vincent in attendance. Lieutenant Bainbrigge informed Logan of the impasse, and Superintendent Spicer was going to read the funeral service. Most. Irregular. Indeed.

Settlement Order

12th September 1829

The Revd. Mr Vincent will immediately send to the Commandant, his reasons in writing for disobeying the official orders he received from Lieutenant Bainbrigge during the absence of Captain Logan that the same may be forwarded for the information of His Excellency the Governor.

By Order of the Commandant.

Logan was accustomed to running the Settlement in a decisive manner, and issuing a formal, public order accusing the Chaplain of disobedience of official orders was nothing if not decisive.

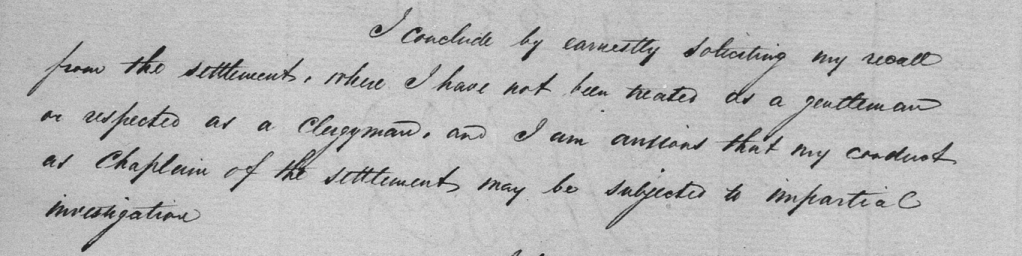

Vincent, no doubt in shock at the abrupt turn things had taken, replied that he was not aware of having disobeyed any orders. Knowing that his career and integrity were about to be questioned at the highest level, he set about making careful copies of the documents that had passed between the parties over the last two days. He wrote his account to the Archdeacon in his final letter of 12 September, concluding with an earnest request to be recalled from his station.

Next door – literally, next door – Commandant Patrick Logan, was writing to the Colonial Secretary. The next vessel to Sydney would be loaded with missives of complaint.[v]

13 September 1829

September 13 1828 was a Sunday, and Chaplain Vincent had duties to perform. In the presence of Captain Logan, Lieutenant Bainbrigge, the military and about 700 convicts, Vincent used the church service to publish the Banns of Marriage between his convict servant, Anne Hall[vi], and Thomas Cribb[vii], free by servitude.

That was the first Captain Logan had heard of this marriage. Most. Irregular. Indeed. Logan wrote to Vincent, demanding to know why this had been done without his knowledge or authority.

Reverend Vincent, apparently now determined to continue his one-man mission to irritate the Commandant, responded that he had followed all the correct procedures, and those procedures did not necessarily involve consulting Logan.

The Commandant decided to send Thomas Cribb back to Sydney to foil Vincent’s plan. That ought to do it.

14 September 1829

Monday 14 September 1829 was a day that threatened to drain the Commissariat of its stocks of ink and writing paper.

Captain Logan wrote to Reverend Vincent, requiring certified copies of letters received from Lieutenant Bainbrigge. When he did not receive a reply, the demand was repeated, together with a threat of official sanction if Vincent did not oblige. And while the Reverend Gentleman was at it, he could explain to the Commandant why the banns had been published without his knowledge?

Reverend Vincent replied that he assumed that Lieutenant Bainbrigge had placed copies of his letters in the orderly book, would provide copies as requested, but did not consider himself legally bound to do so. He did not respond to the question on the banns.

Captain Logan then wrote to Dr Henry Cowper, begging to be informed whether the usual death notification had been made on Collins, and if not, why not. Dr Cowper advised that because Collins had died within minutes of arrival, the prisoner did not appear in his book. Besides, Mr Spicer did that sort of thing.

Having issued the necessary requests and rebukes, Logan set about penning a four-page letter to His Excellency the Governor, enclosing Vincent’s appeal to the Archdeacon and copies of the abundant paperwork the Collins matter had already generated.

20 September 1829

Sundays, for Captain Logan and Reverend Vincent, now involved the unpleasant business of being in each other’s physical presence. Their incendiary letters had been despatched to Sydney, and were being scrutinised by their administrative masters. Both men were convinced that they were morally and legally Right.

It seems that John Vincent just couldn’t help himself. At Divine Service on Sunday 20 September, the Reverend Vincent again published the banns of marriage between Thomas Cribb and Anne Hall or Goodlake. Logan left the room “in the most indignant manner.” When Logan returned, he had his convict clerk give Vincent a copy of a new regulation, forbidding the matter to proceed. Then, the convicts were assembled, and the regulation was read out to everyone, to reinforce the Reverend’s powerlessness. Reverend Vincent did not openly tempt the wrath of the Commandant again.

October and November

The next vessel to arrive at Moreton Bay was the Mary Elizabeth, which docked on 25 October with twelve male convicts and assorted official responses to previous letters. It departed on 27 October with 20 discharged convicts and new letters detailing the affronts suffered by the combatants during the Hall/Cribb crisis.[viii]

Reverend Vincent’s letter to the Archdeacon justified his conduct and adherence to the published circulars and church regulations. Logan’s letter to the Colonial Secretary justified his conduct and adherence to Penal Station regulations. It also explained why this particular challenge to his authority had infuriated him.

Logan had been told that Hall/Goodlake was the worst of the badly behaved female prisoners on the Waterloo. Vincent had not notified Logan of his intention to publish the banns for this unknown woman, who may have already been married. The Commandant saw the second reading of the banns as a direct challenge to his authority.

The Reverend Vincent’s request to be recalled to Sydney had been granted by the Archdeacon, and he was told to return by the next available vessel. That vessel would be the Amity, in December.

Captain Logan, Captain Owens and the Reverend Vincent’s Furniture.

17 – 18 December 1829

Of course, Reverend John Vincent could not leave Moreton Bay without one last controversy. At least this time, it was his furniture, not his actions, that caused the eruption.

On 17 December, the Commandant arrived at the Bay to discharge the Amity to Sydney as usual. He discovered that the Military Guard was sharing the ship’s prison with the convicts, and the hold – which usually housed the Military Guard – was full of Reverend Vincent’s furniture. Most. Irregular. Indeed.

Logan sent a Sergeant on board with a verbal message to the Master, Captain William Owens, desiring that he return the guard to the hold, and stow the cargo with more care.

Captain Owens replied in writing that this instruction could not be complied with, owing to the amount of cargo on board. Owens added that “the Military Guard are more insubordinate than the Prisoners, which circumstance I shall not fail to represent to His Excellency the Governor, on my arrival in Sydney.” Ouch.

Commandant Logan decided to get Official. He wrote to Owens, repeating the request he had made through his Sergeant earlier in the day. No response. He then wrote to Owens requesting that “you will immediately wait on me personally to receive my instructions relative to prepare your vessel for sea. Too much delay has already taken place from your improper conduct.”

Captain Owens came ashore with of two of his crew, at a time of his own choosing, interrupting Captain Logan who was occupied with writing. In “a most unfortunate tone of voice” Owens told Logan to tell him what he wanted to say, while one crewman wrote down the exchange, and another acted as a witness.

What passed between the men that night would have been fascinating, as Owens reported that Logan had “used some very warm expressions casting reflections on my character as a seaman” in an earlier conversation.

Logan wrote an order directing Owens to hand of Command of the Amity to his Chief Mate John Richards, and then wrote a six-page letter to the Colonial Secretary, concluding, “I trust that such conduct will meet with the punishment it deserves.”[ix] It did. Owens was dismissed by order of His Excellency.

Owens spent the month of January 1830 trying to reverse the decision to relieve him of his command. He made his points well, and was granted a meeting with the Colonial Secretary, but one moment of fury back at Moreton Bay doomed his efforts. Logan was able to produce a curt note from Owen, threatening to take him to the Supreme Court. That note sealed Owen’s fate. He had lost command of the Amity.

What the Archdeacon Said.

The most level-headed and reasonable player in the Logan-Vincent dispute was Archdeacon William Grant Broughton, the successor to Archdeacon Scott. Just prior to Reverend Vincent’s departure from Moreton Bay, the new Archdeacon wrote two letters. One to the Governor, the other to Vincent. Both letters demonstrate a fair-minded worldview, and take a tone of conciliation missing elsewhere.

To the Colonial Secretary, Broughton advised. “I entertain much disapprobation of his (Vincent’s) conduct in this unpleasant affair, and adhere to my acceptance of his resignation.” However, he requests that the Governor’s attention be drawn to “one or two points in this dispute wherein it appears to me he has had hard measure dealt to him.”

Of Captain Logan’s conduct, Broughton pointed out the peremptory tone of the Settlement Order, the failure to use a respectful mode of address, given Vincent’s sacred office, and the failure to give Vincent a chance to explain himself before issuing the order.

To Vincent, Broughton explained: “Bearing in mind the awful responsibility and endless anxiety which the Military Superintendent of such a station must incur, your duty is, and your desire, I think, must be, to influence, as powerfully as by words and actions as you are able, the minds of abandoned and desperate men to bear their restraints with submission.” To soften the blow of his censure of Vincent’s activities, he stated that he would always “protest severely against any clergyman being subjected to severe and vexatious treatment,” which the Settlement Order appeared to be.

There was no further attempt to introduce a spiritual influence on the convict settlement at Moreton Bay. A group of German missionaries would undertake a mission at Nundah later in the 1830s, and churches and the clergy came to Brisbane after free settlement. The other “first” Anglican minister at Brisbane, John Gregor, also had a troubled tenure at Brisbane.

Reverend John Vincent continued in his chaplaincy work in New South Wales, passing away in 1854 at the age of 65. He had eleven children, nine of whom survived into adulthood. The eldest, Caroline, lived to the age of 101, spanning the Georgian era to the Jazz Age in her lifetime.

Captain Patrick Logan was criticised for his peremptory attitude in handling the Vincent affair. Logan was murdered in October 1830 during a surveying trip just prior to his intended hand-over of the station to Captain James Clunie. Many weeks after his death, his remains were interred at Sydney Town, following one of the most elaborate funerals the colony had witnessed. His funeral service was read by Archdeacon Broughton.

[i] There had been a riot amongst factions of the women before the voyage, which had required armed military intervention. Some still had open bayonet wounds when they boarded the Elizabeth. The Surgeon would describe the convicts as “worn out with their former debaucheries, poverty and chronic diseases.” He found their conduct appalling, and had reservations about the conduct of the crewmen, one of whom “underwent a sheet examination” as a result.

[ii] Mary Conner died of illness on board on October 18, and Eliza Robinson jumped overboard and drowned. Two of the children of the convict women also died.

[iii] The findings included: The prison locks on the ship had been tampered with, allowing some improper behaviour between the women and the crew. This was not deemed to be the fault of the Captain or the Surgeon. The suicide of Eliza Robinson could not have been foreseen. The board found that the Master of the Elizabeth had not enforced discipline amongst the convicts, resulting in disrespectful behaviour to Vincent and his family. The Surgeon Superintendent was hard of hearing, and the enquiry found that he may not have been aware of the abuse being directed at the clergyman and his wife.

[iv] George Bull per Prince of Orange also died on 10 September 1829. The only other convict to die before Collins in September 1829 was John McElwaine per Regalia, who died on 3 September 1829, but it’s unlikely that his remains would have been left unburied for seven days.

[v] Logan appealed to His Excellency to relieve him of his command if Vincent was not recalled. Because Vincent had asked to be recalled, His Excellency deemed any response to that request unnecessary.

[vi] Anne or Ann Hall (also called Goodlake, and once, Goodluck) ) was born in Bath in 1798. She was convicted of theft at the Somerset Quarter Sessions on 12 July 1819, and sentenced to 7 years’ transportation, per the Morley. She was a laundress by trade, a short, ruddy-faced woman with brown hair and grey eyes.

[vii] Thomas Cribb was a born in Bristol around 1800, and was convicted at Monmouth in 1819, and given 7 years’ transportation per the Agamemnon. He was a sailor, ruddy and freckled with brown hair and hazel eyes. He wore earrings, apparently unusual enough to note on his Certificate. Anne and Thomas both arrived in Sydney Town in September 1820.

[viii] In the letters from Sydney, Vincent had been ordered to return to Sydney on the next available vessel.

[ix] This letter, clearly written in a state of fury, shows Logan barely able to control his penmanship.

1 Comment