Or, how John Stewart occupied himself between the ages of 18 and 25.

The bare facts of John Stewart’s convict career in Australia can be summed up fairly easily – he was transported in 1823, absconded from a few settlements, and received a Certificate of Freedom in 1829. What he actually got up to is far more interesting.

John Stewart hailed from County Antrim, and was sixteen years old when he received a sentence of seven years for stealing a tobacco box. The following year, the Recovery arrived in Sydney Town with John Stewart on board.

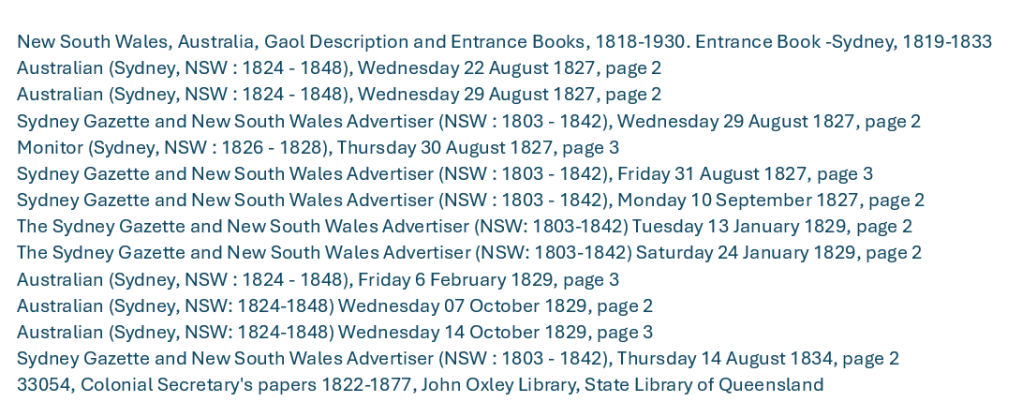

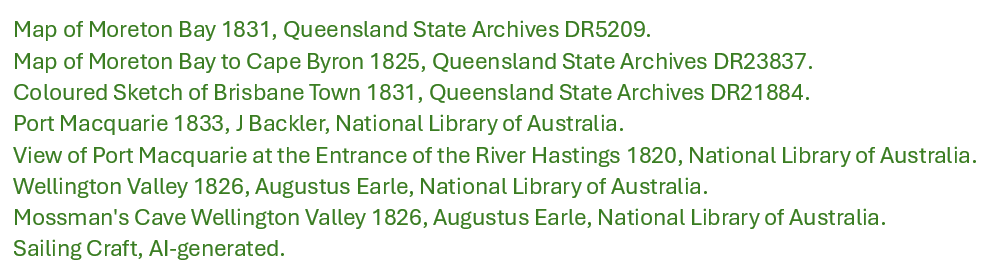

Within a week of landing, Stewart was one of the prisoners sent to Minto, some 35 miles away, to be distributed to work crews. From there, Stewart was sent to work at a small, recently established convict outpost at Wellington Plains, deep in the interior.

In January 1825, John Stewart was reported to have “absented himself” from Wellington Plains. By June, he was located, and sentenced to two years by Magistrate Fennell at Bathurst. Two years meant transportation to a place of secondary punishment, and on 13 July 1825, Stewart was placed on board the Elizabeth Henrietta with nine other prisoners, bound for Port Macquarie.

The Port Macquarie settlement was surrounded by dense bushland, and heavily patrolled by soldiers. Designed to be tough – a place of secondary punishment and hard labour – it does not have the kind of bleak historical reputation bestowed on (earned by?) Moreton Bay and Norfolk Island. Port Macquarie did not suit John Stewart any more than Wellington Plains had. He lasted there less than a year before again escaping into the bush.

July 1826 found Stewart once again in Sydney Gaol, awaiting disposal for running away from Port Macquarie. John Stewart was 21 years old and had scarpered from two settlements in quick succession. There was one place on the mainland remote enough to contain him.

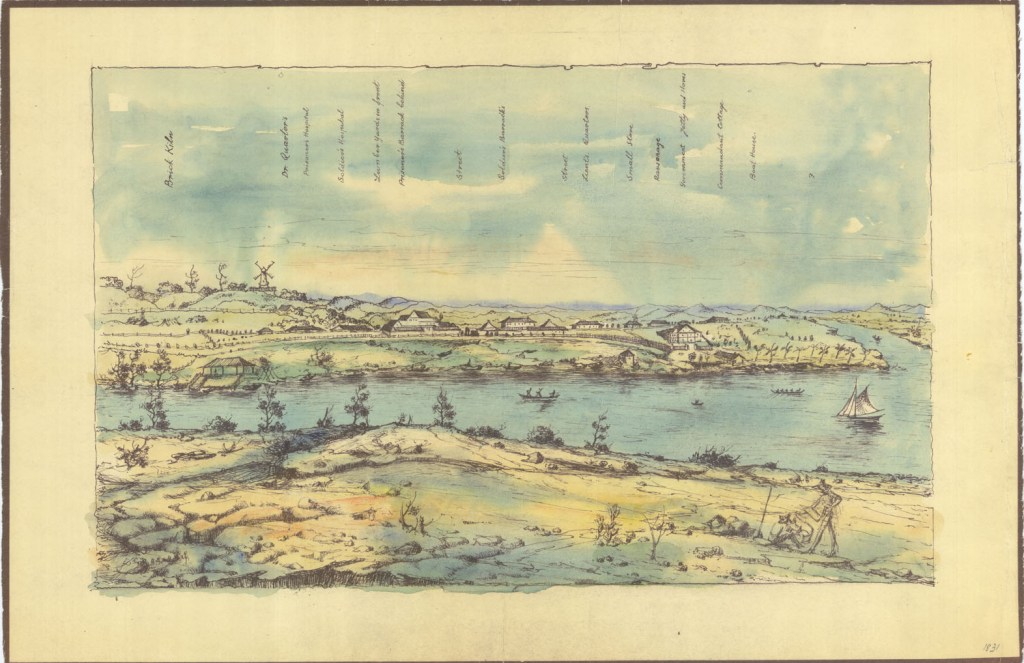

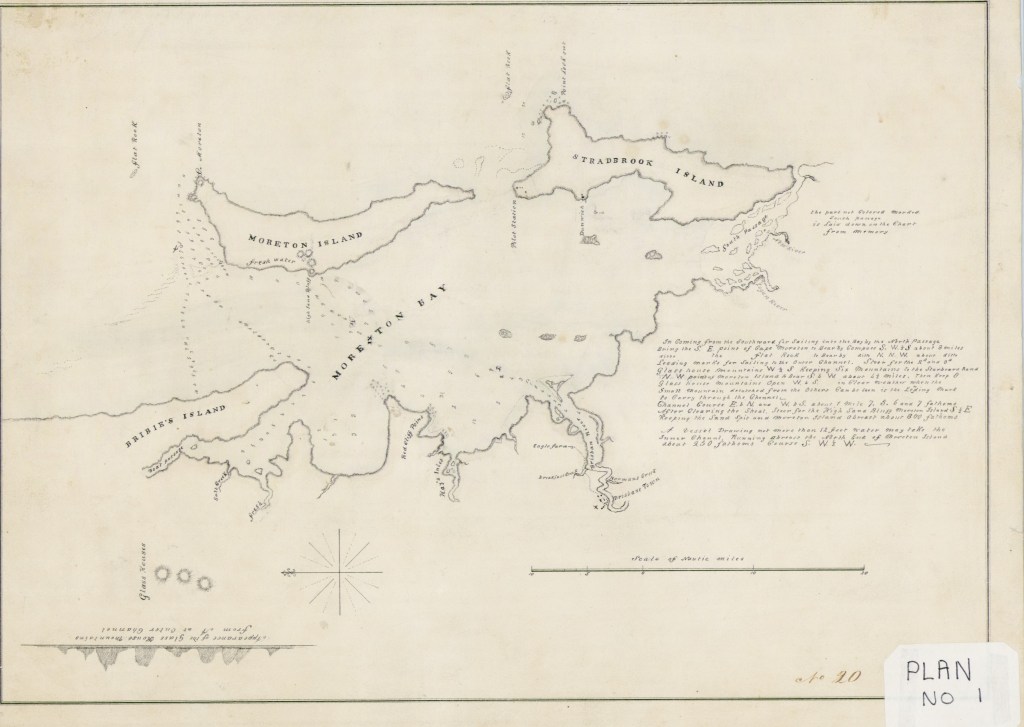

Welcome to Moreton Bay.

The Moreton Bay Convict Settlement had just relocated down the river to Brisbane Town. The new Commandant there was a Captain Patrick Logan of the 57th Regiment, and he had rather a lot of tasks to complete. He was building a gaol, prisoners’ barracks, hospital and windmill, working out how to co-exist with the indigenous people, and exploring the lands around the settlement. He found the convicts at Moreton Bay to be idle and disorderly, and as a result, used corporal punishment rather more than he would have liked (at least that’s what he told the Governor, after some pointed enquiries from the Attorney-General)

When the Amity arrived at the Bay in September 1826, one of the prisoners had been caught stealing flour from the cargo hold. That prisoner was John Stewart, who was promptly given 50 lashes on disembarking. Welcome to Moreton Bay.

Stewart really didn’t like Moreton Bay. The Commandant was too strict. The rations were too light. The work was too heavy. He found himself regretting his premature departure from Port Macquarie. On 16 January 1827, Stewart ran from the Brisbane Town.

John Stewart had now run from three settlements, and had spent some months in the bush each time. He had clearly learned bush survival skills, as well as finding a way to interact in a friendly manner with the various groups of indigenous people he encountered during his bushranging days.

In late June 1827, after six months on the run, he turned up at Port Macquarie. There were three other Moreton Bay escapees there at the time, and the Commandant, no doubt exasperated by the never-ending stream of visitors from the North, formally interviewed the men.

The Port Macquarie Statements.

John Stewart’s statement included the whipping he received on arrival, and alleged further corporal punishment for complaining about his rations being short. He stated that he had been expected to break up 15 rods[i] of new ground in a day, “which he neither could, nor would, do” and was put on half rations for seven weeks as a punishment. He claimed to have been out for three and a half months, but the time between absconding and the statement was closer to six months.[ii]

William Dalton of the Lord Eldon reckoned he’d been on the run for six or so months. He left Moreton Bay because of the rations and work[iii].

Thomas King per Baring 2 was another man who’d been transported to Moreton Bay for running away from Port Macquarie, a decision he had also come to regret. His problems included rations, work and ill-treatment by Overseers[iv].

Edward Mullen per Neptune had volunteered to Moreton Bay. He’d liked Lieutenant Miller, but not Captain Bishop, who had sentenced him to Norfolk Island (for building an escape boat). Mullen had not yet been sent to Norfolk Island, but his property and tools were taken from him. Some Commandants are so touchy – all he did was try to flee the country! He said he’d been on the road for two months.

All four runaways were returned to Moreton Bay on the Wellington on 20 July 1827, along with 44 men being transported from Sydney. All four tried their luck at absconding again. Dalton absconded twice before completing his sentence in 1834. The other three absconded permanently – Thomas King in November 1827, Edward Mullen in February 1829, and Stewart on 15 June 1828.

Captain Logan had been provided with a copy of the statements of the Port Macquarie Four, and practically snorted his response to the Colonial Secretary. “They have never been required to do more work than is generally performed by Prisoners throughout the colony assigned to settlers and what they call half Rations is the Ration No 7 in the Printed Regulations ordered for Prisoners in Gaol Gangs. Stewart’s statement that he received fifty lashes for complaining of the scantiness of his rations in entirely false – he never received any corporal punishment on the settlement except for breaking into the hold of the Brig Amity and stealing flour.” So there.

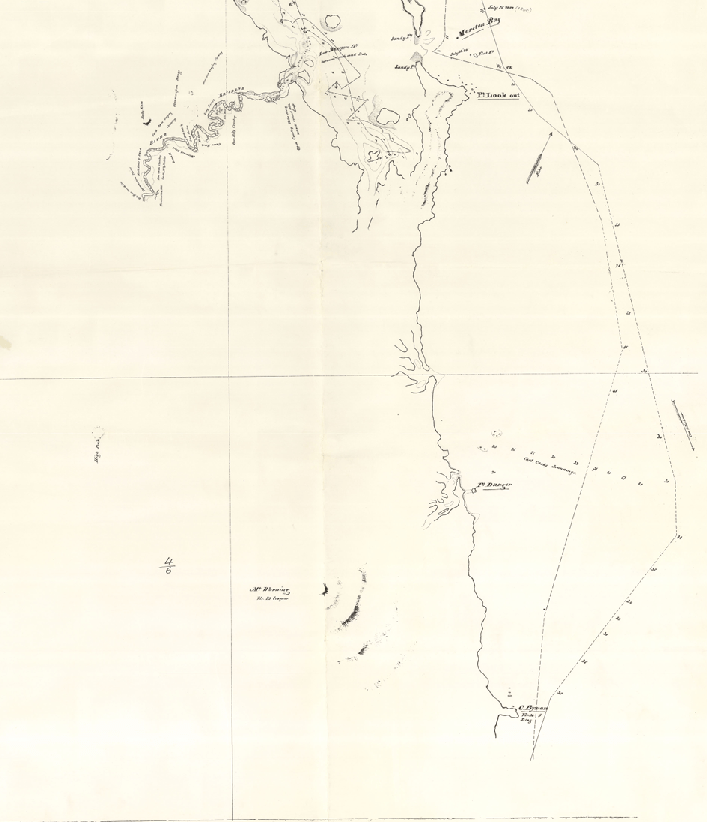

Another matter was occupying the authorities in Sydney and Brisbane – John Stewart claimed to have seen a shipwreck lying on the bank of a river mouth north of Port Macquarie. Captain Logan questioned Stewart closely, and instructed the master of the Alligator to make a thorough search of the coastline on his return to Sydney. Logan’s instinct was that the story was a work of fiction, but decided to do his due diligence.

A Shipwreck?

Apprehensions are entertained for the safety of the ship Elizabeth, Captain Powditch, as she is some months overdue, still however, it is thought that she has gone upon some coasting voyage or other.

Australian, August 1827.

Reports of a shipwreck north of Port Macquarie had been circulating in Sydney in August 1827. David Maziere of the firm Berry Wollstonecraft wrote to the Governor, concerned that the wreck might be the Elizabeth, which had been due to return from South America months earlier. The Australian and Sydney Gazette published the description given by Stewart – a three masted ship with a female figurehead, white streaks on the sides and a coppered deck.

The Master of the Alligator, William Barkers, was tasked with looking for the wreck, and found nothing on his journey to Moreton Bay. On the return voyage, Barkers decided to take a whale boat to inspect a large river near Cape Byron and ask the local indigenous people if they knew anything about a shipwreck. Not only was his search fruitless, but he also couldn’t relaunch the whale boat. In the end he had to abandon it.

While Barkers was wading miserably around the northern rivers, the Elizabeth arrived safely in Sydney bearing wheat, walnuts, soap, raisins and a clergyman.

John Stewart, no doubt being kept under a very close watch at Moreton Bay, deferred any plans to scarper until June 1828. On 15 June 1828, the Pine Party (which I suspect was a sawyering expedition, not a social occasion) found itself short five men. Thomas Allen,[v] Francis Mulligan,[vi] Daniel Ready or Reidy,[vii] George Williams,[viii] and John Stewart all absconded.

When (inevitably) caught, every Pine Party escapee was ordered to return to Moreton Bay on the City of Edinburgh. Everyone arrived at the Bay on 21 January 1829, except John Stewart.

The Mutiny on the City of Edinburgh.

In the early hours of Sunday 11 January 1829, the ship City of Edinburgh was lying in Sydney Cove, ready for a journey up the coast to Moreton Bay. Over 140 convicts were on board. All were recidivists, having committed offences in the Colony after having been transported from their home countries. Some, like John Stewart and John Smith, had been to Moreton Bay before, and were not relishing the prospect of more hard labour in the heat under the command of Patrick Logan. Others were dreading the prospect, facing even longer in chains through their own actions.

Tensions grew in the night, and some of the most troublesome prisoners prised up some boards in the coal hold scuttle. There was a rush of prisoners over their bread, two escaped overboard, and the soldiers guarding them opened fire. Six convicts were taken to hospital. One died.

The first convict to escape into the water was found quickly, and brought back by the ship’s boat. The second convict to jump overboard was John Stewart, and he was last seen swimming towards the North Shore. It was not considered likely that a man wearing heavy irons would survive in the open water.

Two Justices of the Peace, George Bunn and Thomas Raine, went on board the City of Edinburgh, took statements and inflicted corporal punishment on nine of the convicts who were considered to have been the ringleaders.

The JPs who attended the City of Edinburgh on the night of the mutiny proudly presented their findings to His Excellency the Governor. They had acted with dispatch, punished the main actors, and the ship was able to continue the voyage to Moreton Bay without delay. The response the JPs received from the Colonial Secretary was unfailingly polite, but also scathing:

“I am directed by His Excellency to communicate to you his thanks for the zeal which you showed on that occasion; but His Excellency has commanded me to submit to you whether it would not have been more regular to have reported the disturbance on board of the ship in question to the Principal Superintendent of Police immediately after it came to your knowledge rather than to have proceeded as you did … because the legality of these punishments has been questioned.” Oops.

And the missing man, John Stewart? By 13 January, the Sydney Gazette was reporting that Stewart was known to be a strong swimmer. “A day or two previous to the riot this man, though heavily ironed, went over the ship’s side, with a rope fastened to his body, and brought up a musket, which had accidentally fallen overboard, from the bottom, in 9-fathom water.” Adding, “We have just heard that this man, who is known by the name of Scotch Jack, succeeded in making the shore and was apprehended yesterday morning at Lane Cove.”

Denouement.

John Stewart, still only 24 years of age, had escaped from Wellington Plains, Port Macquarie, Moreton Bay (twice), and a mutiny-struck transport vessel. There was no place left to send him but Norfolk Island, and he was transported there on board the Isabella on 5 February 1829. Looking at his record, one would be forgiven for thinking that Stewart was doomed to spend a long time on that isolated outpost. In fact, John Stewart was returned to Sydney per the Isabella on 4 October 1829, and was granted a Certificate of Freedom on 15 October 1829.

Why Stewart was released and given his freedom nine months after escaping during a mutiny, the record does not disclose. The voyage of the Isabella that brought him back to Sydney also brought witnesses in the trial of former Norfolk Island Commandant, and a convict charged with attempted murder. It’s possible that Stewart was a witness in the second matter, or had taken a deal with the prosecution for evidence.[ix]

Stewart’s name does not appear in convict records after the Certificate of Freedom was granted. However, the name John Stewart, known as “Scotch Jack,” does appear in a newspaper story in 1834. It may be the same John Stewart.[x]

[i] Around 248 feet, according to a unit calculator online.

[ii] His account of his time on the road involved meeting a “very friendly” tribe in the mountains, and living with them for three weeks. Heading south by the coast, he met and lived with another group for a month, only leaving when it was proposed to scarify him as an adoption process. Another indigenous group helped him across a large river in their canoe. Finally, about 60 miles north of Port Macquarie, he met a less friendly group who “cruelly beat and maltreated him.”

[iii] He’d lived amongst the indigenous people, who treated him well. At one point, he met Stewart, but they parted company about two hundred miles north of Port Macquarie.

[iv] He was treated well by indigenous people on his journey, but was emaciated on arrival at Port Macquarie.

[v] Per Marquis Hastings.

[vi] Mary 1

[vii] Hadlow 2

[viii] Eliza 2

[ix] Commandant Wright was charged with the murder of a prisoner in 1827. He was found not guilty of that murder. This was two years before Stewart’s stay on Norfolk Island.

[x] “Scotch Jack” in this case had sold some cattle – claiming it was on the order of his employer – to a butcher, who was charged with receiving stolen goods. “Scotch Jack” had made himself scarce by the time the butcher’s matter went to court, and he was mentioned only in passing.