On this day – 22 August 1848.

On 22 August 1848, Colonel Kenneth Snodgrass was elected to represent Moreton Bay in the New South Wales Legislative Council. He was our second ever elected representative after free settlement in 1842.

Brisbane turned out to vote in numbers. Small numbers. There were 32 votes for Colonel Snodgrass, and 22 for his opponent. (There might have been more votes cast had Ipswich been permitted to have a polling place, and had anyone who had ever actually lived in Moreton Bay been on the ballot.)

The Predecessor.

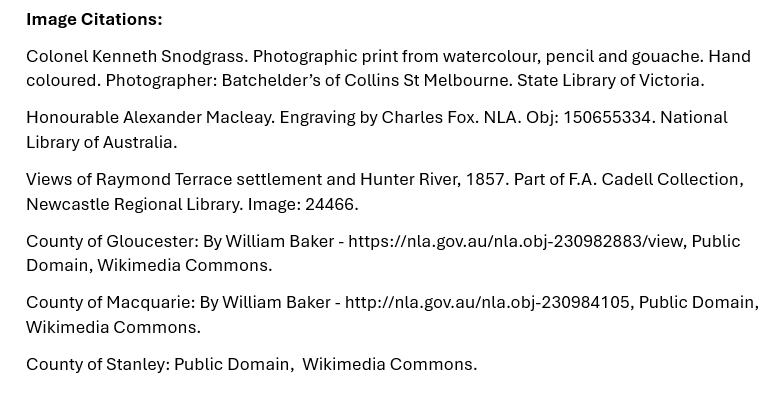

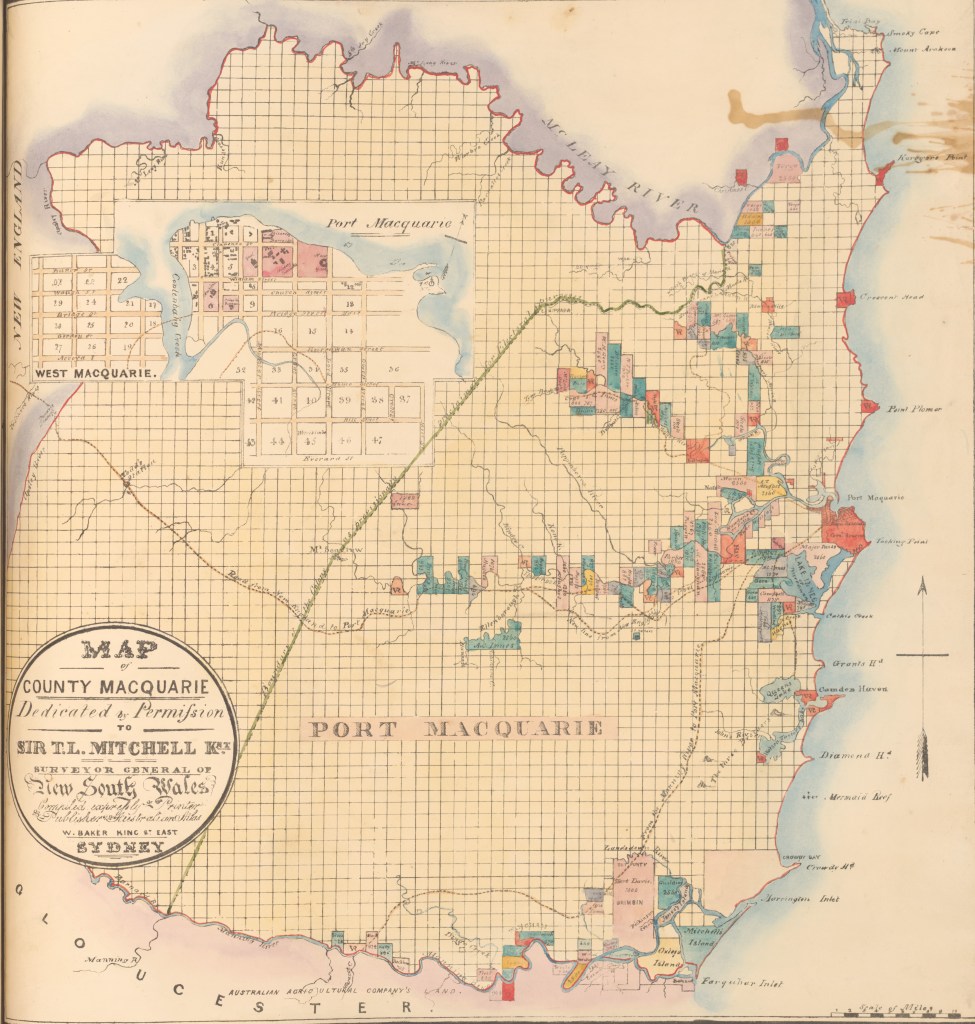

The first person elected to represent the interests of anyone north of the Tweed River was former Colonial Secretary and avid lepidopterist Alexander Macleay, in 1843 [i]. Then in his late 70s, he was elected to the districts of Gloucester, Macquarie and Stanley, an enormous chunk of the eastern coast of Australia.

By early 1847, the Courier wondered whether he should resign his post as Member for Gloucester, Macquarie, and Stanley, “the duties of which, owing to his increasing years and infirmities, he is no longer able to fulfil.” That… sounds familiar.

The Counties of Gloucester, Macquarie and Stanley – most of the east coast of Central and Northern New South Wales and Southern Queensland.

Macleay lingered on until deciding not to re-contest the August 1848 election, dying shortly after making that decision.

Our Man in Raymond Terrace.

The way was clear for Snodgrass, who won by 10 votes and published a letter to his new electorate. (He hadn’t campaigned here, of course – it was 400 miles by sea from his home at Raymond Terrace.)

The Courier wrote,

“On the whole, we must come to the conclusion that there is nothing violently objectionable in the views of Colonel Snodgrass.”

That was about as enthusiastic as the Courier, or indeed any of his far-flung constituents felt about Colonel Snodgrass, a man whose early career had been heroic and action-packed. His later career in politics was undistinguished, although he did inadvertently lay the groundwork for a massacre, and nearly drove his next-door neighbour mad.

Kenneth Snodgrass was born in Paisley, Scotland in 1784, and joined the armed forces at eighteen. Napoleon was in the throes of a long campaign to conquer Europe, and Kenneth Snodgrass fought longer and harder than most in the many wars to repel the French leader. He seems to have been both incredibly brave and resourceful as a soldier, and was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in 1817. By that time, however, Snodgrass had received a severe head wound, and saw out his service as a brigade major in Sydney, not willing to retire from military life but unfit for active duty.

In the 1830s, Colonel Snodgrass entered the administrative life of New South Wales. At one point, he was briefly Acting Governor of New South Wales, and in his few months in office, managed to set off a chain of events that eventually led to the Waterloo Creek Massacre of indigenous people.

When not doing official things, Snodgrass was busy upsetting people. His often pointlessly stubborn behaviour might have been the result of his head injury in 1815. He certainly brought the tenacity of his fighting days to civil disputes, and was known to be wildly impatient with civilians, certain branches of the Presbyterian church, and his neighbours.

The Reverend John Dunmore Lang was one notable who found Snodgrass upsetting. Following a row over Presbyterian stipends, in which Snodgrass was technically correct, Lang decided that he showed ‘an obtuseness of moral feeling.’

The Neighbour From Hell.

Another example of his obtuseness was a dividing fence dispute between Snodgrass and his neighbour at Raymond Terrace, James King. King had built a fence on the boundary of his property, and found that the Snodgrass family, particularly the sons of the worthy Colonel, used his land as a short cut. They had no compunction about destroying sections of the fence in the process. King repaired his fence and politely supplied the Colonel with a gate key, to allow the various young Snodgrasses to pass through without destroying the fence. The fence continued to suffer assaults, and some of King’s timber was cut down.

King felt he really must protest, and wrote to Snodgrass as one respected Colonist to another. Colonel Snodgrass wrote back, challenging King to a duel [ii], “I can hold no further communication with you, except to give you the usual explanation which I will do even to a person in your station of society and shall be at Raymond Terrace the whole of tomorrow, for this purpose.”

King forwarded the letter to the Attorney-General. Snodgrass was convicted and fined £100 for inciting a duel [iii]. That was in 1842. Snodgrass was still making Mr King’s life difficult as late as 1851. He tried to open a public road through King’s property on two occasions, no doubt using his position in the Government to further his schemes to torment his neighbour.

In 1849, the Courier noted that Colonel Snodgrass had shown a faint, but encouraging, degree of interest in the remote northern corner of his electorate, although it was aware that the old veteran was close to retirement.

Colonel Snodgrass retired in September 1850 and passed away at his home in Raymond Terrace in late 1853. In Sydney, people published poems, obituaries and portraits for weeks afterwards. The Moreton Bay Courier noted his passing in two sentences.

Richard Jones, another respected old Colonist, but one who actually lived in Brisbane, was elected to fill Snodgrass’s vacancy in the County of Stanley.

[i] He had been given 14 votes in Brisbane Town.

[ii] Duelling was a Snodgrass family passion. The third of the Snodgrass sons, Peter, engaged in two public duels in his adopted town of Melbourne. On both occasions, his gun went off prematurely; on the first, he shot himself in the foot.

[iii] Snodgrass didn’t help his case in any way by stopping King in the street and snarling, “You are a lying blackguard, and if you tell any more lies about me, I will beat you with this stick.”