A re-issue of a previous post, dealing with the group of convicts who ran from Moreton Bay in 1825.

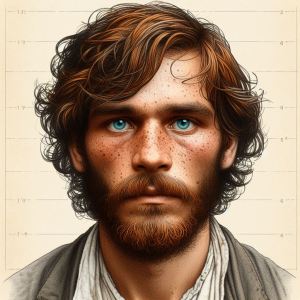

Thomas Mills

Robbing the Vicar of Stepney

St Dunstan’s Anglican Church, Stepney, known as the “Mother Church of the East End,” had been a place of Christian worship for more than 900 years when Thomas Mills, a 17-year-old sailor from Newcastle, decided to inspect the contents of its rectory. On 31 March 1819, at 11 am, Francis Whitehouse, a servant to the Rev. Thomas Barneby, noticed the kitchen door was open and heard someone rifling around some drawers. He raised the alarm and discovered one Thomas Mills hiding under another servant’s bed. He was searched, and a £10 note was found in his pocket, and four £1 notes were scattered around him. He was given in charge to the headborough, who located a brooch hidden in the boy’s shirt. All the items found were the property of Rev. Barneby.

Mills said and did nothing to defend himself, and at the Old Bailey trial the following day, he was found guilty of stealing and sentenced to death (with a recommendation to mercy). Mills sat in Newgate for two months before the respite from hanging was given. He went to the Justitia Hulk at Woolwich, then embarked upon a one-way journey to the Colonies on the ship Eliza.

Visiting the Penal Settlements of New South Wales

The Eliza arrived in Sydney at the end of January 1820, and Mills and his shipmates were sent to Emu Plains, deep in the countryside, to join the Government Agricultural Establishment. The following year (1821), he was no. 70 of 104 prisoners assigned to work under William Cox, Esq., Magistrate and roadbuilder [1], a man who made no secret of his ambition to eradicate Aboriginal Australians from the face of the earth.[2] Spending time in his service would have been arduous and dispiriting.

In April 1822, he had broken a three-year crime drought, and had been sentenced to a further two years at Newcastle per the Eliza Henrietta, after a short stay in Sydney Gaol. Things were quiet until Mills and five other prisoners absented themselves from the Cedar Party in March 1823. (The Cedar Party probably wasn’t nearly as festive as it sounded.) The delinquent sawyers were also suspected of some robberies in the district. Mills received 25 lashes, courtesy of Colonel Morrisset.

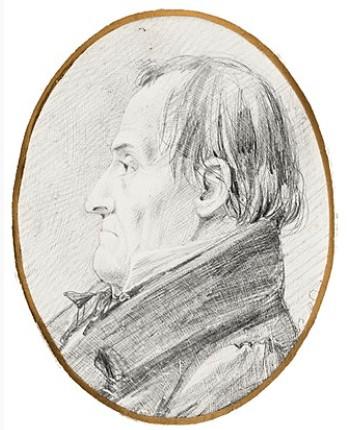

By September 1823, he was removed from Newcastle to Port Macquarie, in order to serve that sentence for robbery dating back to March 1822. June 1824 saw Mills back in Sydney gaol, and due to be embarked on the Lady Nelson to Port Macquarie (again). Presumably, that plan was changed, and Mills found himself on a list of twelve serving prisoners [3] to board the Amity for a place called Moreton Bay.

Moreton Bay

The Amity arrived at Redcliffe on 14 September 1824, with provisions, soldiers, volunteers and some very unhappy convicts. This group had to build the settlement from nothing. There were sandflies, fresh drinking water shortages, and a population of indigenous Australians who were not pleased to have all these strangers arriving on their land without invitation. Nearly twelve months later, the settlement was packed up and taken into the interior to what is now Brisbane. They hadn’t been in the new spot long before Thomas Mills, together with John Longbottom, John Welsh and William Smith deserted, probably by stealing a boat.

The four runaways arrived at Port Macquarie on 18 November 1825, claiming variously to have walked for five weeks along the shoreline, or have hijacked a boat at Moreton Bay in a murderous mass escape.

The men were in the cells when John Longbottom called out to the Gaoler, and asked if he could make a statement about their escape. His account included this passage, about Mills:

After this Mills said “I never liked a red coat (meaning the soldier) in my life, I’ll run the bayonet through him” which he instantly did, through the lower part of his breast and killed him on the spot. The soldier at this time was lying on his back from the severe beating he as well as the constables had received with sticks and the butt-ends of the muskets, and when Mills stabbed him, Smith said “That’s right.”

John Longbottom’s deposition, 1825.

Longbottom further claimed that nine men took the barge from the settlement, but were shipwrecked on the journey south, with the loss of five lives.

The Commandant at Port Macquarie took the depositions and forwarded them to the Governor, with a copy for the Attorney-General. The prisoners were to be forwarded to Sydney to be dealt with, although Commandant Gillman doubted the story of a journey overland and advised that he was sending a party to look for the boat they had used.

And then … very little happened. No charge of murder was laid against Thomas Mills, and only one report of the alleged murder appeared in the newspapers, and it was inaccurate as to the location of the alleged murder and the number of victims.

“A dreadful murder has been lately committed at Port Macquarie by nine prisoners. The victims are two soldiers and two prisoners. The murderers, after committing the deed, seized a barge belonging to the settlement, and made off with it. The boat was upset by the surf and five of the runaways drowned. The others made for the shore and were secured and are now in custody.” Australian (Sydney, NSW: 1824 – 1848), Thursday 8 December 1825, page 3.

The subsequent news reports contain no mention of the murder, just some cynical reports about the story of the five-week journey by land.

Thomas Mills was sent to Sydney Gaol, and was then ordered to return to Moreton Bay per the Amity on 30 August 1826. He spent six months back at the settlement, and was discharged to Sydney on 6 January 1827. His stealing charge from 1822 was officially revealed in the Register – “Stealing oranges and (being) an incorrigible character.”

As Incorrigible as Possible

Thomas Mills was back in Sydney Town, and decided to continue being as incorrigible as possible. Here are the highlights:

1827: Running away from Carter’s Barracks. Six months to an iron gang.

1828: Running away from his iron gang. Sent to Campbelltown.

Running away from his iron gang again. Another six months to an iron gang.

1829: Being a notorious runaway, robbing and absconding. Two years to a penal settlement.

1832: In gaol at Newcastle.

1837: In Sydney gaol awaiting trial.

1838: Admitted to Sydney gaol four times, then sent to an iron gang.

1840: Admitted to Newcastle gaol twice.

1841: Admitted to Newcastle gaol for fourteen days.

1843: Admitted to Newcastle gaol.

1845: Ticket of Leave – to remain at Parramatta.

1847: Charged with robbery, sentenced to three years in chains, and admitted to Darlinghurst gaol.

1848: Sent to Norfolk Island.

1850: Ticket of Leave – to remain at Carcoar.

1852: Ticket of Leave cancelled by Carcoar Bench for being illegally absent.

And then, nothing until his death on 18 May 1868[4]. Perhaps spending the better part of three decades in gaols and at penal settlements finally convinced him that crime didn’t pay. But at least he hadn’t murdered a soldier at Moreton Bay. The Commandant, Regiment, Governor, Attorney-General and Colonial Secretary would have noticed if that had happened.

[1] Well, the convicts did the actual building – so much faster and cheaper than private labour.

[2] Appin massacre | The Dictionary of Sydney

[3] James Hazel, Lewis Lazarus, James Burns, John Anderson, Thomas Mills, John McWade, James Turner, William Saunders, John Pearce, Henry Allen, Thomas Bellington, and John Walsh alias Cartwright. Only Bellington, Allen and Pearce did not abscond.

[4] The Convict Records website gives this information and quotes a source that I have not been able to locate.