James Byrne – the man of several names.

One of the Amity convicts was recorded as James Byrnes, per Asia 2. He also went by James Burns and John Burns. To further confuse, there were two convicts named John Burns aboard the Asia in 1822. One was tried in Liverpool, the other Surrey.

In the convict indents, the Liverpool John Burns was 16 years old, a Liverpudlian, a shoemaker, 5 feet 4, with a florid and freckled complexion, black hair and hazel eyes. He was convicted at Liverpool on 21 January 1822, and received 7 years. The Surrey John Burns was 19 years old, hailed from Greenwich, worked as a reaper, was 5 feet 3 1/4, and had a much-freckled complexion with black hair and grey eyes. He also received 7 years.

Two very young men of very similar appearance arriving on the same ship makes it hard to know which of these people turned up at Moreton Bay, but the Chronological Register, Description Book and other correspondence indicate that the Liverpool John Burns was the correct man.

John/James Burns/Burne/Byrne was forwarded to Liverpool (which doubtlessly confused him, coming as he did from the original Liverpool) for distribution after arriving in Sydney in July 1822.

In March 1823, Burns was sent to Port Macquarie to serve out his original sentence there. He absconded, and was admitted to Sydney Gaol on 2 June 1824. There were by now 10 Port Macquarie absconders there, and His Excellency was pleased to decree that these men were to be forwarded to Moreton Bay on the Amity.

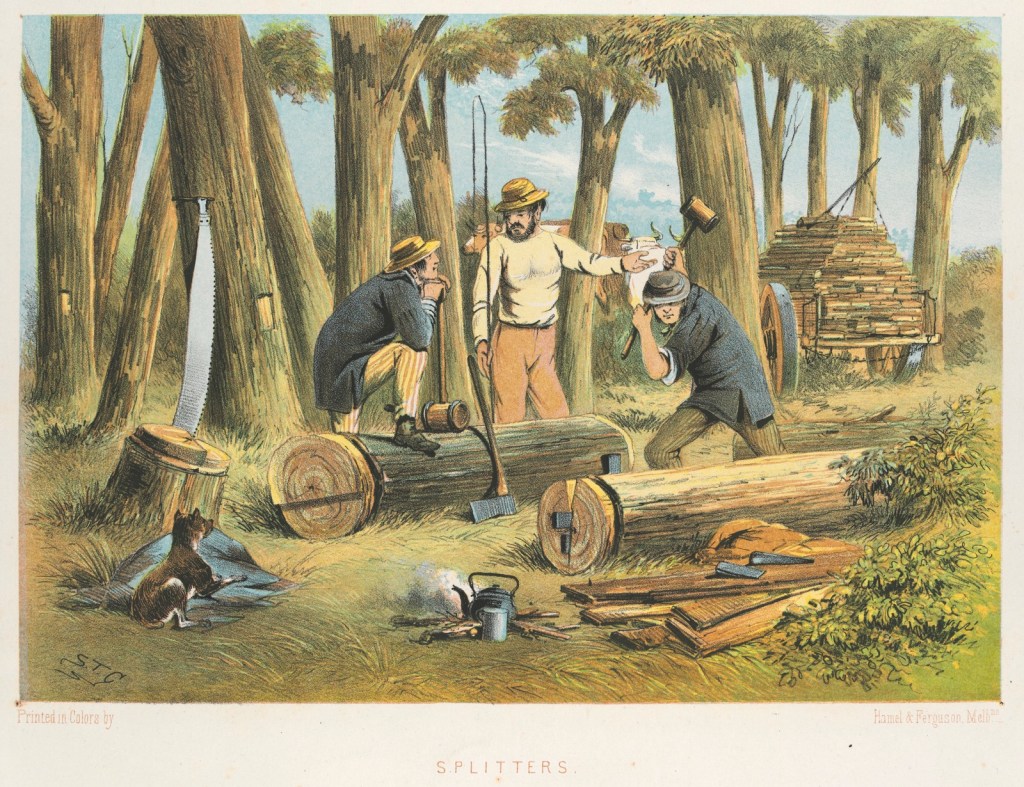

John Burns seems to have had an industrious 2 ½ years at Moreton Bay. He was recorded as “felling timber, burning off, destroying stumps and breaking up ground” in 1825 and 1826. On 6 January 1827, his original sentence had expired, and his hard work had paid off. He received a ticket of leave to remain in the District of Evan, and did not trouble history again.

James Winstanley – the convict success story.

James Winstanley was sentenced to death for housebreaking at the Surrey Lent Assizes 1819. He was very young – barely sixteen, and must have thought his world was ending. The sentence was respited, and he was sentenced to fourteen years’ transportation instead.

James was a shingle splitter, a trade that made him a welcome addition to the list of convict volunteers to Moreton Bay. He worked “splitting shingles, falling the timber and cutting” – which frankly sounds exhausting – for two years. He returned to Sydney in October 1826, aged 23.

In 1828, he received a Ticket of Leave, and in the 1830s he married, started a family, and received a Certificate of Freedom.

He spent the following years working as a carpenter, and growing his business acumen, becoming one of the most successful former convicts in New South Wales. He passed away in 1882.

John McWade – the sailor turned brewer.

John McWade was an Irish seaman who received a seven-year sentence of transportation at the York Assizes in November 1818. He was transported to New South Wales on the Canada.

On arrival, he was already 36 years old, with the a dark, pock-pitted complexion, black hair and dark eyes. McWade was sent to Liverpool for distribution, and in his first years in the colony was assigned to a lot of hard graft. He was on a Road Party at Parramatta, then “Mr Bayley’s Clearing Party,” and “Thompson’s Road Party.”

He understandably grew tired of clearing bush and building roads, and fled one of the gangs. He was apprehended and sent to Port Macquarie in 1823. Whatever he was asked to do there was not to his liking, and he absconded. Upon recapture, he was in Sydney Gaol, contemplating a sentence to Macquarie Harbour, Van Diemen’s Land, when the Superintendent of Convicts sent him to Moreton Bay on the Amity instead.

John McWade returned to Sydney to a Certificate of Freedom. His original sentence expired, and he was free to make his new life in the colonies. In 1832, he applied to marry Jane Smith, alias Johnson at Newcastle. He occupied himself as a brewer and distiller, and passed away in May 1862.

Evan Williams – stealing the live, tame fowls of Camden Town.

On 4 June 1818, Camden Town resident William Roberts rose and checked his fowl-house as usual at 7 am. There was a distinct lack of fowls. All that remained were a few feathers lying about the stable.

On the same day, an officer named Henry Croker was sent to the lodgings of two young jackanapes – Evan and James Williams – to look for some missing leaden pipes. He didn’t find any pipes, but, on searching the premises, found two bags under a bed, containing a total of seven fowls.

I’m guessing the fowls had been killed before Croker conducted his search, or the amount of bustle and racket coming from under the bed would have given the game away immediately.

Evan Williams swore that he bought them for 18d the previous afternoon, but William Roberts identified the birds and knew that they’d been nestled happily in his fowl-house the previous afternoon.

Evan Williams was transported for seven years. A swarthy-looking young man, he worked as a sawyer and joiner and volunteered to Moreton Bay in 1824. He served his two years, then returned to the usual Ticket.

In late 1827, there was an administrative headache at the Colonial Secretary’s Office. His Excellency was absent in the interior and could not endorse Evan Williams’ replacement Certificate. That was a bit awkward – Williams had been given written leave from the Superintendent of Convicts to board the ship, Harmony. Presumably, he was allowed to go, but the passage of time and leakage of ink on the page does not offer a conclusion.

John Williams – from picking pockets in Whitechapel to respectability.

It was high summer 1822 in Whitechapel when Robert Hendry felt what any watch-owner in London actively dreaded – the surreptitious tug in the pocket. Hendry was walking along Whitechapel at 10 pm – he wasn’t sure which young rapscallion took his watch, because his eyes weren’t too keen. At any rate, there was an alarm raised, and two youngsters ran. John Williams was grabbed as he ran down an alleyway – a watch was found on the ground a few feet from where he was caught.

On that evidence, 19-year-old John Williams was sent to New South Wales in irons. He arrived aged 20, a fair-haired young man with a slightly pock-marked face. He was a blacksmith, and when he arrived in the New World, he was put to work with William Henry.

John Williams volunteered to go to Moreton Bay on the Amity in 1824 to reduce the length of his sentence. He worked as a smithy, naturally, “preparing and repairing tools for the building of the settlement.”

When he returned to Sydney two years later, he received the first of a series of Tickets of Leave, permitting him to live and work in the District of Sydney.

In 1834, Williams married Phoebe Clegg, the free-born daughter of two early convicts. John and Phoebe had nine children over the years, and John passed away in March 1873, aged 69 years.

Thomas Warwick – the absent husband.

Thomas Warwick was a sawyer from Surrey, who stole sheep at Hornchurch. This, naturally, attracted the death sentence when he appeared at the Essex Lent Assizes of 1819. He was respited, and was transported to New South Wales for life on the Malabar.

He worked in Parramatta, and married a young lady named Anne Treble. Reverend Samuel Marsden blessed the union in 1823, and in March 1824, their first child, John, was born.

Thomas volunteered to Moreton Bay, arriving there at the age of 32. Thomas spent his time on the sawyer’s gang with William Francis, “sawing pine and hard wood for public use.” He did the standard two years of a volunteer, returning in October 1826. Now, he only had to wait another year to receive his Ticket of Leave.

The long absence at Moreton Bay did nothing positive for his marriage, sadly. By the 1828 Census, Ann was living with another man – a convict named Francis Allsop.

John Pearce – the waterman who couldn’t stay out of trouble.

The 19th century waterman lived and worked on the rivers of England and its dependencies. A waterman would take passengers across and along the waterways in small craft – rowing boats or sail boats. They were the essential to the life of any settlement on a waterway.

John Pearce’s story is noticeably similar to those of his fellow Amity prisoners – particularly those who were drafted from Sydney Gaol in 1824. He was tried at Southwark in 1818, when he was a teenager. He received transportation for seven years for larceny, and fetched up at Sydney in 1819.

He was sent to Parramatta for distribution. He was labouring at Eastern Creek in 1821, when he was arrested and charged with stealing and killing a calf “the Goods of our Lord the King.” He was found not guilty, but the Judge Advocate suggested that he and his co-accused might be better off going to another part of the colony to finish his original seven year sentence. You know, somewhere suitably distant, away from the King’s calves.

Pearce was sent to Port Macquarie in March 1822, but absconded and found himself in Sydney Gaol on recapture. He was forwarded to Moreton Bay on the Amity.

Pearce left Moreton Bay on 09 January 1826. He arrived back in Sydney a free man, and received his Certificate of Freedom on 23 January 1826.

On 24 January 1826, Pearce and a Sydney criminal named William Murphy were arrested for “having committed a gross and violent assault on the person of Samuel Arnold, at the hour of ten last night, in the street.”

Both men were found guilty, and sentenced to a year in the house of correction. The Gaol Description and Entrance Book for Sydney Gaol seems to show that he was discharged on the day he was sentenced.