Brisbane gradually developed a theatre scene in the 1860s. Population growth spurred a desire to see entertainments beyond improving lectures at the School of Arts, travelling circuses and magic lantern shows.

1860s Brisbane played a small, but vital, part in the growth of a theatrical dynasty that would be celebrated throughout Australia and “home” in England. In fact, a star was born here.

In 1863, a young English chemist named Charles Robert Merevale Jennings settled in Brisbane with his wife Emily and their infant son. In October 1864, the Jennings welcomed a daughter at their Petrie Terrace home. Her name was Elizabeth Esther Ellen Jennings, who would become the young Queen of Shakespearean acting under the stage name Essie Jenyns.

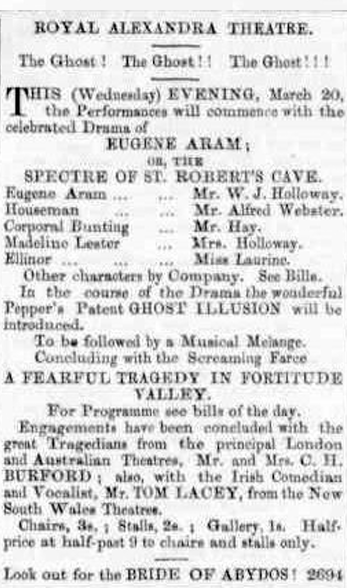

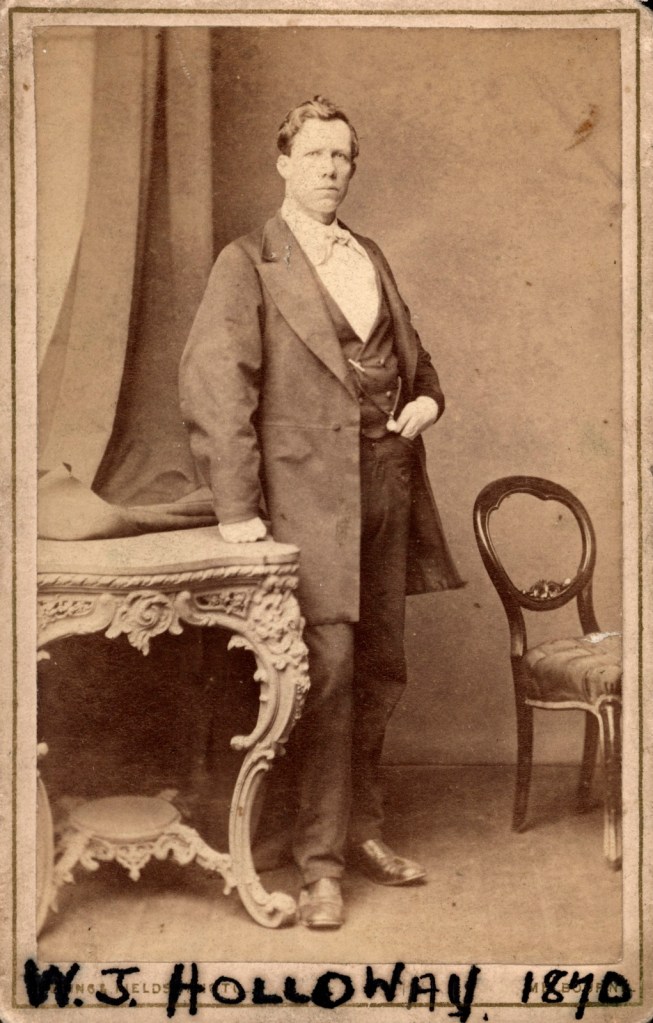

A couple of years later, William John Holloway, an Englishman who had appeared in amateur dramatics in Sydney, appeared in Brisbane for the first time as a professional performer, in the pantomime season. Holloway made regular visits and had lengthy stays in Brisbane as he refined his craft.

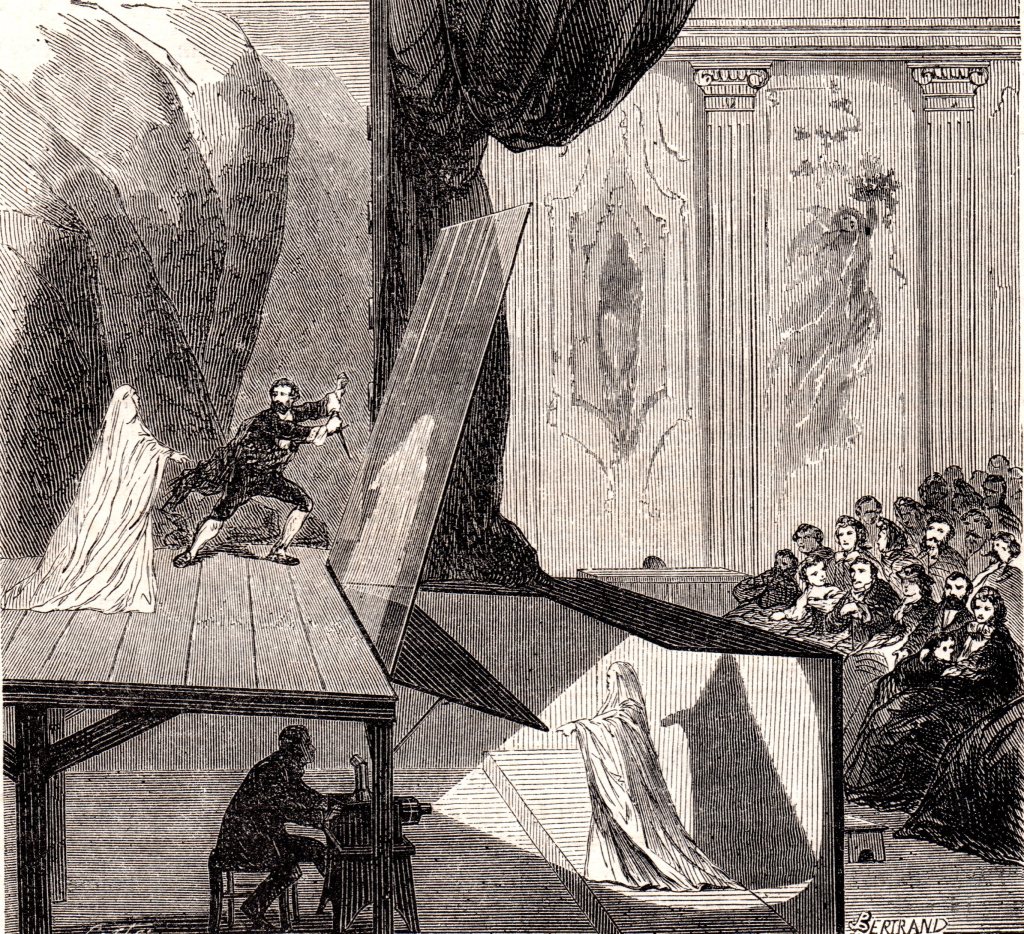

In 1867, WJ Holloway was a featured actor (along with his then wife) in the Queensland touring production, “Eugene Aram or the Spectre of St Robert’s Cave.” This production featured the “Pepper’s Ghost” illusion. Audiences were thrilled from Brisbane to the goldfields. Mainly with the ghost illusion, it must be said – the ghost had better notices than the actors. (Regrettably, the “screaming farce” set in Fortitude Valley was neither reviewed nor explained.)

Holloway remained in Queensland until 1868, and was farewelled with a benefit night prior to joining the Victoria Theatre company in Sydney.

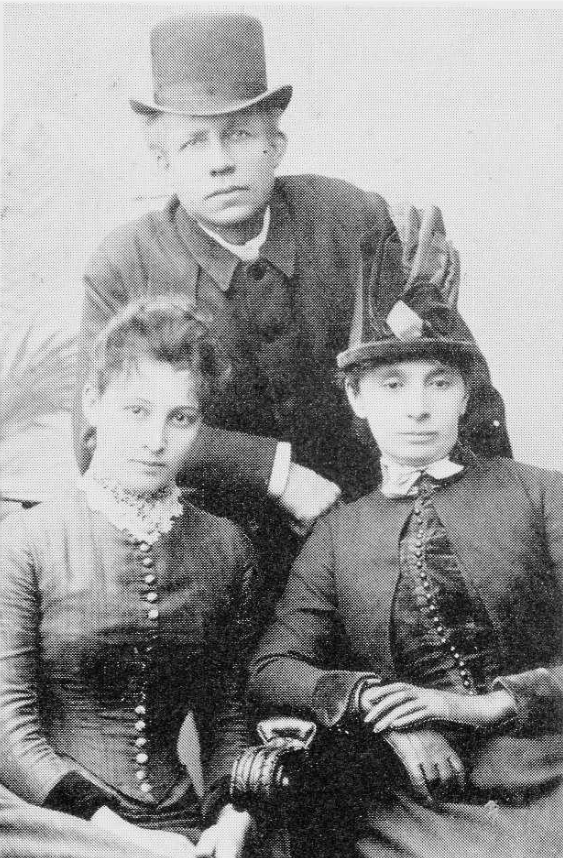

Charles Jennings died in 1871, leaving his widow casting about for ways to support herself and her two young children. Emily Jennings gamely went on the wicked stage as Kate Arden [i], and joined the WJ Holloway touring company in 1872. As the 1870s progressed, two daughters were born to Mr Holloway and Mrs Jennings, and they married in 1877 (the first Mrs Holloway having by then passed away).

The Holloways.

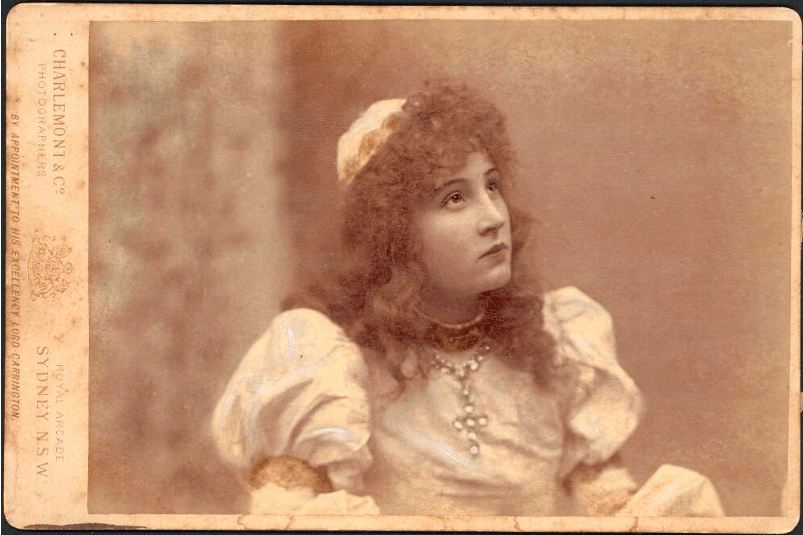

The Rising Star.

Essie’s mother and stepfather toured extensively through Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, and the little girl showed aptitude in child roles. She began to appear in speaking roles, and was so successful that she was taking on larger supporting roles by fifteen.

From 1882, the Holloways started including Queensland in their annual touring schedule, and Essie’s growth as an actress and an audience favourite can be seen in her notices.

Miss Jenyns – a very young actress, who is, we should think, destined to make a mark in her profession – was a bewitching Mathilde, full of grace and vivacity.

Brisbane Courier, 1882.

Miss Essie Jenyns, as Bess, at once enlisted all the sympathies of the audience on her side. Her acting showed a delicate appreciation of the pathos of the part, and she acted with a winsome grace and refinement that stamped her at once as an actress of no ordinary abilities. In scenes where there was every temptation to “rant” she substituted a quietness of suppressed emotion that was infinitely more pathetic. In short, it was a most artistic and refined rendering of a part that might have been written for her.

Brisbane Courier, 1883.

As Ruth Hope, Miss Essie Jenyns fulfilled my anticipations – in fact exceeded them. She is natural and free from that staginess which is all the more prominent in other members of the company. She has a fine part and it does not suffer in her hands.

Queensland Figaro, 1884.

In 1885, Essie did not visit Brisbane – she was taken to London by her mother and step-father with a view to trying her luck there. For various reasons, she did not get a role. Oversupply of young actresses already in London, stated Holloway. Prolonged ill-health, stated Essie. One of Essie’s peers, Nellie Stewart, claimed that Essie was overworked by Holloway and suffered poor health.

Essie did take in performances from her idols whilst abroad. She saw Sara Bernhardt in “Theodora,” Irving in “The Bells,” Irving and Terry in “Faust,” and two performances by Mary Anderson – “Parthenia” and “Juliet.” (Mary Anderson, the American actress known for her beauty and naturalistic acting style, would be the actress with whom Essie was most often compared in the following years.)

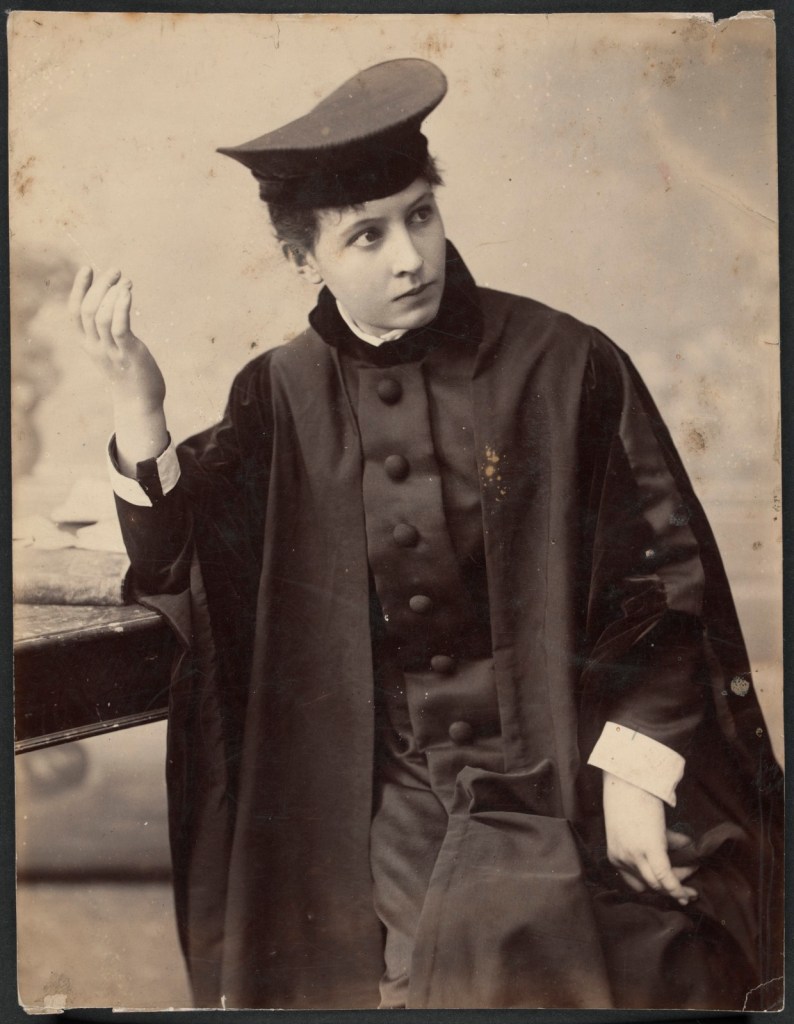

The Shakespearean Actress.

Back in Australia in late 1885, Essie and the Holloway Company undertook exhaustive seasons and tours throughout the colonies from 1886-1888, concentrating on prestige roles designed to show off their undoubted star.

In her 1886 season in Brisbane, she created a much-lauded Juliet. She was 22 years old by that time, breaking a tradition of somewhat matronly Juliets in the late 1800s. Her notices suggest that she was a genuinely moving, powerful and lovely Juliet, but it is hard for this modern reader to ignore the fact that she was playing Juliet to the Romeo of her 47 year old stepfather.

A more perfect ideal Juliet than Essie Jenyns on the balcony it would be difficult to find. The light and shades of the character are well brought out. She is loving and beloved, fearful yet joyful, hopeful yet desponding, never anything but a girl of quick appreciable fine temperament. She sees the difficulties in her path, but love is her god, she will worship none but him. When the nurse’s voice was heard calling within her acting was very fine and her hesitation between her lover and her duty was plainly manifested.

And so throughout the remaining scenes in the boudoir with Romeo she is the fond, affectionate young bride. When she takes the sleeping potion she rises from playful acting to tragic force and power. Her horror at the scene she may see in the tomb if she awakes before the time makes her tremble and afraid, but love masters all, and she “drinks to Romeo.” Again in the final scene of the tragedy in the tomb of the Capulets, where she wakes and finds her Romeo dead, poisoned for love of her, her acting is intense. She stabs herself with her dead love’s dagger and falls at his feet. She creeps along painfully until she lies by his side, and then with a faint smile and sigh of relief, as though she had found a heaven from her troubles at last, she dies.

Telegraph, June 1886.

In the 1887 season, as well as continuing Juliet with her stepfather, Essie portrayed Portia (to slightly mixed notices), Viola, (to ecstatic notices), and Rosalind:

The playful vivacity and deep feeling, and the keen appreciation and pretty use of mimicry, were finely contrasted with the emotional anguish with which she receives the napkin stained with her lover’s blood.

The Brisbane Courier, May 1887.

The Brisbane season was marked with a little sadness. Audiences knew that Essie would be headed back to London to try her luck. Essie was always careful to acknowledge her home town during the visits to Brisbane, and when not on stage, she attended benefits and made public appearances where her beauty and exquisite dress sense made the news.

By September 1888, the Holloways had made firm plans to take Essie to London for her debut. The company was disbanded, and Essie was the subject of a long interview with Centennial Magazine:

Miss Essie Jenyns continued by giving some information as to her future plans. Mr and Mrs Holloway do not wish her to make her debut in London before next May.

“If I go to London in my youth, surely that will be in itself a strong appeal to the kindly consideration of the London playgoer and the London critic.”

On representing Australia in London, “I shall feel inspired, and shall do my best to uphold the honour of my native land.”

The article then states that “Miss Jenyns is not engaged to be married – a fact which she enunciates with playful emphasis.” (There had been whispers as early as February 1887 that Essie had lost her heart to a young man, and would marry and leave the stage.)

A wedding and a riot.

Just as the Holloways were packing for a journey to London of at least a year, rumours of Essie’s possible engagement appeared again. In November, her engagement was announced – she would marry John Robert Wood, a very wealthy young man from Newcastle (New South Wales).

The wedding was announced to take place in Sydney in December 1888. The Holloways would not be in attendance, having decided to continue with their plans for London (they had other stage-struck daughters, after all).

It’s fascinating to speculate what went on when John and Emily Holloway found out that the young woman – who had worked to near exhaustion across five colonies and more than ten years for them – had decided to live her own life. People didn’t discuss that with the press in those days. And because those things were not discussed, there was only ever a rumour that John Wood paid a small fortune to Holloway to buy Essie out of her contract, and compensate for the loss of future earnings. At all events, the Holloways left for England, somewhat wealthier, in November 1888. They remained there.

Essie’s wedding was marked by uncouth behaviour from members of the public, who created a crush and caused damage in the cathedral, which may have caused Essie to faint (accounts vary as to the extent of the damage to the church and the distress of bride). The most restrained account of the wedding follows:

The building was crowded to such an extent that the wedding party could scarcely push their way through, and at the close the crushing was so great that not only was much damage done to the fittings of the cathedral, but many ladies and children were very roughly jostled, not all the efforts of her friends being able to protect the bride from this unmannerly mob. No doubt this discreditable incident may be partly attributed to the popularity of the bride, her many admirers, especially from the region of the ‘gods’ being certain to turn out in great force to her wedding, and from one of the telegrams it would appear that the reason for the rush at the close as a desire on the part of those present to secure some memento of the wedding.

Telegraph, December 1888.

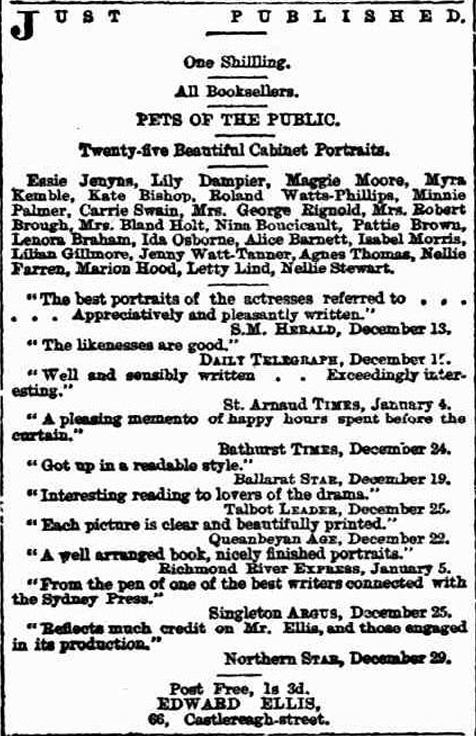

Essie was probably the first home-grown ‘star’ in the modern sense. Her carte-de-visite photographs used in this article were still selling briskly a year after she left public life. The photography studio who took them estimated that 15,000 copies had been sold by 1889 alone. In the language of the day, she was the principal “pet of the public.”

Essie Jenyns, or Mrs Robert Wood, was now 24 years old. Apart from a special appearance with Ellen Terry in Sydney in 1914, she never appeared before an audience again. The Woods had a family, travelled the world by yacht, lived in beautiful homes, and contributed to charity. Essie died in 1920.

The Holloways continued their success in England, with WJ replacing an ailing Henry Irving in “King Lear” at short notice, and scoring a personal triumph. The Holloway company, now including Essie’s stepsisters Juliet and Theodora and son William Jr, toured South Africa several times to great acclaim.

[i] Oddly, though, there was an actress named Kate Arden active in Sydney in 1866. At first, the artist seems to be an imported performer, but this advertisement suggests otherwise: BENEFIT TO MISS KATE ARDEN. – A complimentary benefit to Miss Kate Arden (Mrs C Jennings) is announced for tomorrow (Thursday) evening, to be given at the Masonic Hall by the Amateur Backus Minstrels. The programme states that the entertainment is to be patronised by the Premier, members of the Ministry, and the Mayor and Aldermen of Sydney. (Sydney Morning Herald, 1866.) Perhaps Mrs C Jennings went on stage during her marriage to Charles. In which case, as an actress, she might have had the opportunity to spot the rising talent, WJ Holloway, in Brisbane in the 1860s.