On 23 May 1872, a weak and emaciated elderly man was admitted to the Woogaroo Asylum [i], after spending quite a few years at the Benevolent Asylum at Dunwich, Stradbroke Island. By early August, the man had developed a terrible cough and could no longer leave his bed. The Asylum staff were able to get him to eat a little arrowroot and sago, washed down with beef tea, but the man didn’t rally, and he died at 8:10 pm on 27 August 1872.

An inquest was held the following day, at which it became clear that the Asylum staff were more concerned about ensuring that they (and the institution) weren’t held responsible for the old man’s wretched condition [ii]. It also revealed that they knew very little about their patient – even his age.

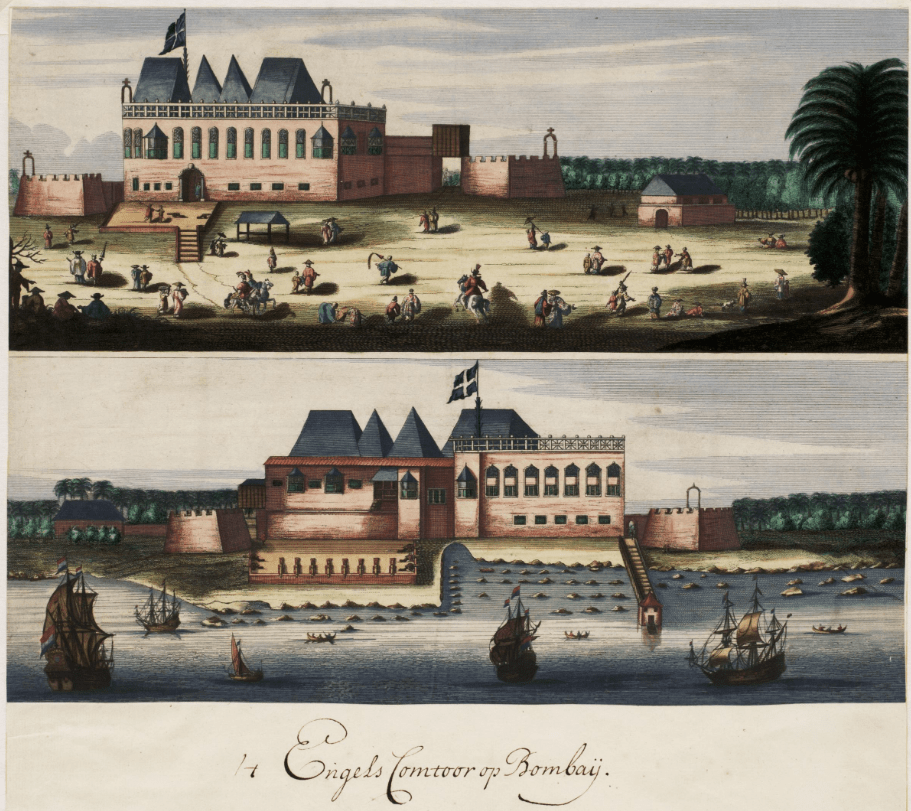

The man who died so miserably among strangers was named Abraham Freeman. He came from a distinguished family background in Ireland and had served with the Bombay Infantry. While in India, he made a terrible decision that led to a life of wandering through rural New South Wales and Queensland, taking menial jobs when he could, before being punished and then institutionalised for being old and poor.

Abraham Freeman was born in Ballyhaise in County Cavan in 1800 to William Freeman, attorney, and his wife Phoebe Ferguson. Records of his life are scant, but he was recorded as joining the Cavan County Freemasons in December 1817, with his brother, Robert.

Twenty years later, he was transported to New South Wales on the convict ship “Hind,” one of seven soldiers sent from Bombay in British India. Of his shipmates, two had been convicted of desertion, one with attempting to strike a serjeant, and two with striking a serjeant.[iii] The other six men had been court-martialled at Bombay.

Not Abraham Freeman, though. He had been convicted in the Bombay Supreme Court on 22 March 1838 of shooting at a serjeant and had been given a life sentence. In a later account Freeman gave of his experiences, he described the matter as being “sent out for duelling.” I’m inclined to believe that, only because had Freeman made a murderous attack on a serjeant without being in a duel, it is probable that he would have been executed without delay.

On arrival in New South Wales, he was described very thoroughly in his Convict Ident. He was 5 feet 4 ½ inches tall, with a dark, sallow and freckled complexion, brown hair and hazel eyes. He could read, was single, Catholic, and had lost a couple of incisor teeth. When he checked in at Sydney Gaol prior to being assigned, the records there unkindly added “stout” to that description.

Freeman went to Maitland, where he remained until his Pardon was granted in September 1850. It was “available everywhere, save in the UK of Great Britain and Ireland, and Bombay.” He was free to go outside the Maitland district, and he tried his luck on the diggings before going back. He remained there, only racking up a fine or two for being drunk. As he aged, work became scarce, and he tried his luck in the new Colony of Queensland in 1861.

What he apparently didn’t know is that he was being sought by his family and friends back in Ireland. They didn’t know where he’d fetched up in the colonies, but they seemed to be aware of his Pardon having been granted. Earnest advertisements started appearing in newspapers everywhere. Everywhere that is, except the places Freeman actually was.

Should Mr Abraham Freeman of Ballyhaise, County Cavan, Ireland, communicate with the undersigned, he will hear of something greatly to his advantage. F.C. Singleton. Adelaide, 29 July 1851.

ABRAHAM FREEMAN, late of the 2nd European Infantry, formerly of Ballyhaise, County Cavan, Ireland. Any information respecting Mr Freeman will be thankfully received by Hugh O’Reilly, at this office, 58 Chancery-Lane, Melbourne. 18 July 1856.

These advertisements repeated over the years but seem to have missed their target. Finally, a clergyman was appealed to, and he in turn appealed to the Colonial Secretary in New South Wales.

29 October 1859

The Rev. Robert Hogg presents his compliments to the Chief Secretary (Sydney) and requests that he will cause inquiry to be made of the whereabouts of Abraham Freeman, who gained a conditional pardon in 1850.

His friends in Britain are anxious that they may get him to send them the “Power of Attorney” to recover some money that belongs to him in right of his poor wife, Eliza Freeman, who has been dead since March 1839.

The Parsonage, Horsham, Victoria

Freeman had been married; it appears. His wife had died exactly one year after her errant husband had been given a life sentence. The Colonial Secretary’s office requested a search of the records of the Convict Department, and replied to Hogg, “The man above named I am informed left Maitland some years ago and has not since been heard of.”

Had the Colonial Secretary’s office instigated a police enquiry, Abraham Freeman might have been located. He didn’t leave for Queensland until 1861.

1861, coincidentally, was the year the second appeal came from Revd. Hogg to the New South Wales Colonial Secretary.

Revd. Robert Hogg, St Stephen’s Manse, Bathurst. To the Honourable Colonial Secretary, Sydney.

Sir,

I beg to request that you will cause inquiry to be made respecting Abraham Freeman, who lived in the District of Maitland from the year 1838 up to November 1850 when he obtained his liberty to go out at large. His friends are anxious to know his whereabouts since a “Power of Attorney” is wanted by his brother Robert to recover some property that belonged to his wife – Eliza Freeman (alias Reid). I remain your obedient servant, Robert Hogg.

This second letter stirred the Colonial Secretary to order the Police Commissioner to cause an enquiry and report back. The Police advertised in newspapers and the Police Gazette well into 1862, but to no avail. Nothing further had been heard of Abraham Freeman.

Back in Ireland, Robert Freeman must have been grinding his teeth – the power of attorney never arrived. One suspects that Robert Freeman’s anxiety over his brother’s whereabouts was not entirely devoid of self-interest.

Abraham Freeman, meanwhile, was living and working in the Ipswich area for a man named Darby McGrath. They got on well enough, until Abraham had to take action to recover some wages. Every shilling counted. Still, Freeman was kind enough to part with a hard-earned pound to a charity subscription.

Unfortunately for Freeman, the Ipswich Police Magistrate could not abide the presence of loafers going about being unemployed and looking shabby in his town. He was fond of sending poor people to prison – usually for a month and usually with hard labour. So, Abraham Freeman, aged 64, spent Christmas 1864 in the Petrie Terrace Gaol in Brisbane in order to atone to society for the sin of poverty. He was grey-haired, no longer stout, and had apparently shrunk an inch in the nearly thirty years since his arrival in Australia.

Ipswich Police Court.

Tuesday, December 20. (Before the Police Magistrate and Mr Leith Hay.) Abraham Freeman, having neither lawful means of support nor a fixed place of abode, was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment.

In October 1865, Abraham Freeman was admitted to the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum, giving his age as 70 and omitting any mention of a brother in Ireland, or a long-dead wife. The ailment that caused his admission also wasn’t noted. Freeman was open about his past as a convict, which he hadn’t been at the Brisbane Gaol, where he claimed to have arrived free. He spent most of the next six years at Dunwich, until he was noted as “discharged in custody 20 May 1872.”

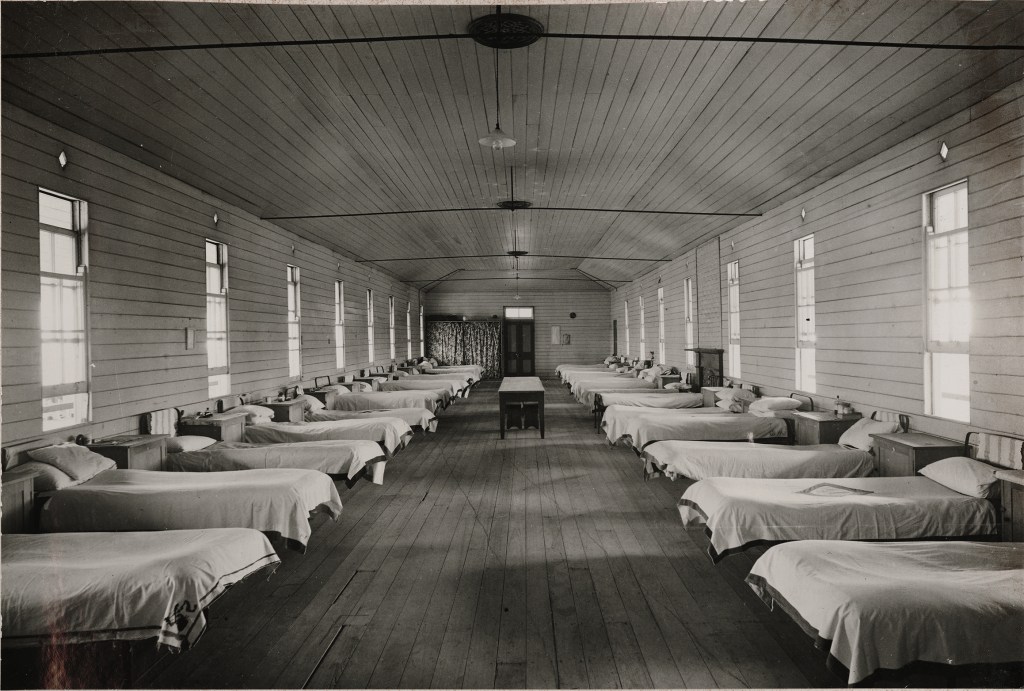

By that time, Abraham Freeman was 72 years old, and his health had worn down. He travelled from Moreton Bay to Woogaroo in three days, arriving at the Asylum “thin and emaciated.” Perhaps Freeman’s mental state had declined with age and infirmity, and he became unmanageable in the fairly isolated setting of Dunwich. But it seems rather brutal to remove a dying old man from a Benevolent Home to Woogaroo.

Abraham Freeman, whose life began with promise and ended being shuffled between places of refuge for the sick, was buried at Woogaroo.

Particulars of a Magisterial Inquiry touching on the death of one Abraham Freeman, late a patient in the Lunatic Asylum. Held at Woogaroo before Mr Goggs Esq on the 28th August 1872.

Patrick Keans being duly sworn states: – Abraham Freeman was admitted as a patient into the Hospital on 23rd of May 1872. He was thin and emaciated when he was admitted. He took to bed on Sunday the 11th of August, and has been on the bed ever since. He had corn flower, sago and arrowroot, wine and beef tea, according to the Doctor. He coughed much. I did not see him die. I know nothing of his age.

John Mannion being duly sworn states: – I am a night warder at the Asylum. I saw Abraham Freeman in the Hospital last night. He did not ask for any food or drink from me in last night. He was bedridden. He did not cough last night. He died at ten minutes past eight o’clock and I saw him expire.

Thomas Jesse on oath states: – I am Chief Warden of the Asylum. I knew the deceased, Abraham Freeman. He was admitted to this Asylum on the 23rd of May of the present year. He was brought from the Lunatic Reception House at Brisbane, but was, according to the records, originally in the Benevolent Asylum at Dunwich. I produce the Asylum Case Book, in which the particulars of this case are fully entered. He appeared to be about 70 years of age.

Charles Prentice being duly sworn states: – I am the acting Surgeon Superintendent of the Lunatic Asylum. Abraham Freeman was in the Hospital Ward when I took charge of the Institution. He died of effusion In the brain following a severe attack of bronchitis.

Charles Prentice, recalled, states: – The cause of his death was effusion into the ventricles of his brain, following on bronchitis. The bronchitis would be accelerated by the night wind coming through the unglassed parts of the Hospital windows.[iv]

Verdict – That Abraham Freeman died from effusion on the brain and bronchitis.

[i] At the time, the official name of the place was the Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum.

[ii] The coroner recalled Dr Prentice, the acting Surgeon Superintendent, who had to admit that the Hospital ward where the deceased had been had unglazed windows, and the night breezes would not have helped the man’s recovery.

[iii] Not, presumably, the same serjeant. One hopes.

[iv] The Colonial Secretary made a marginal note on his inquest file to have the unglassed windows attended to.