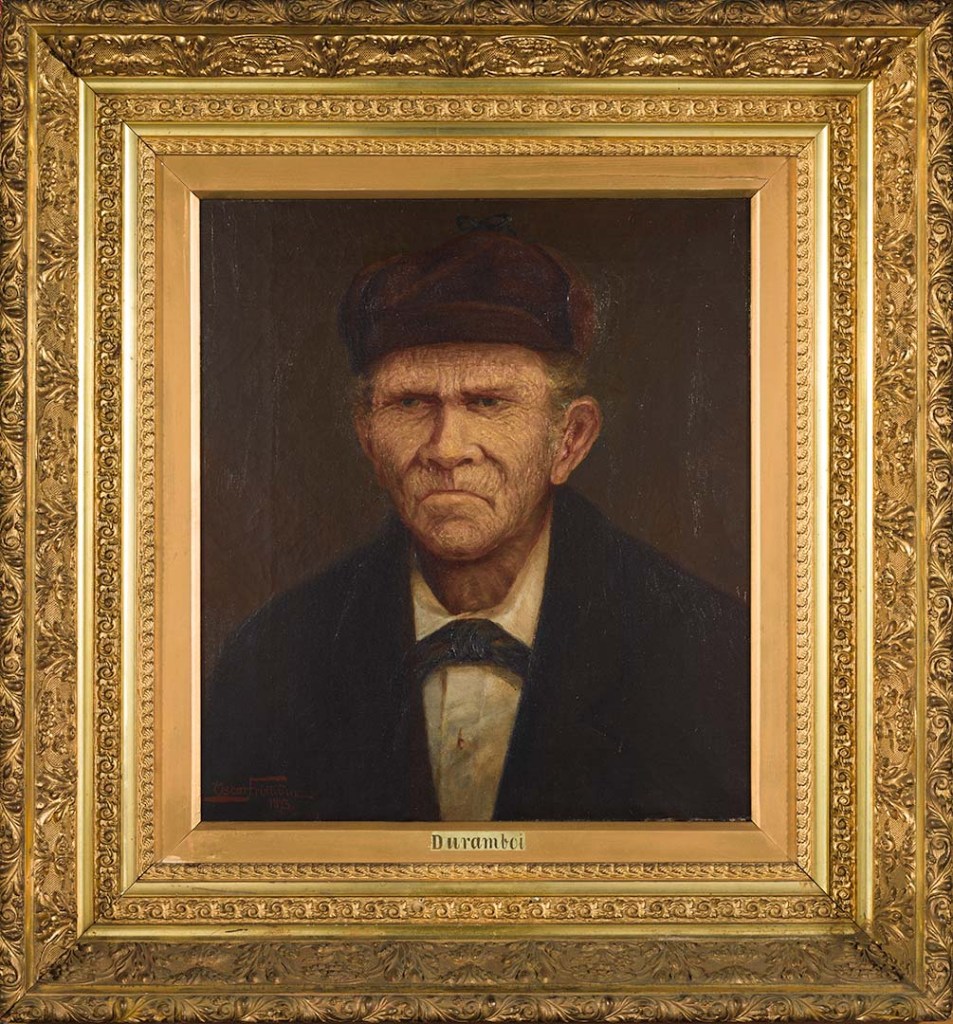

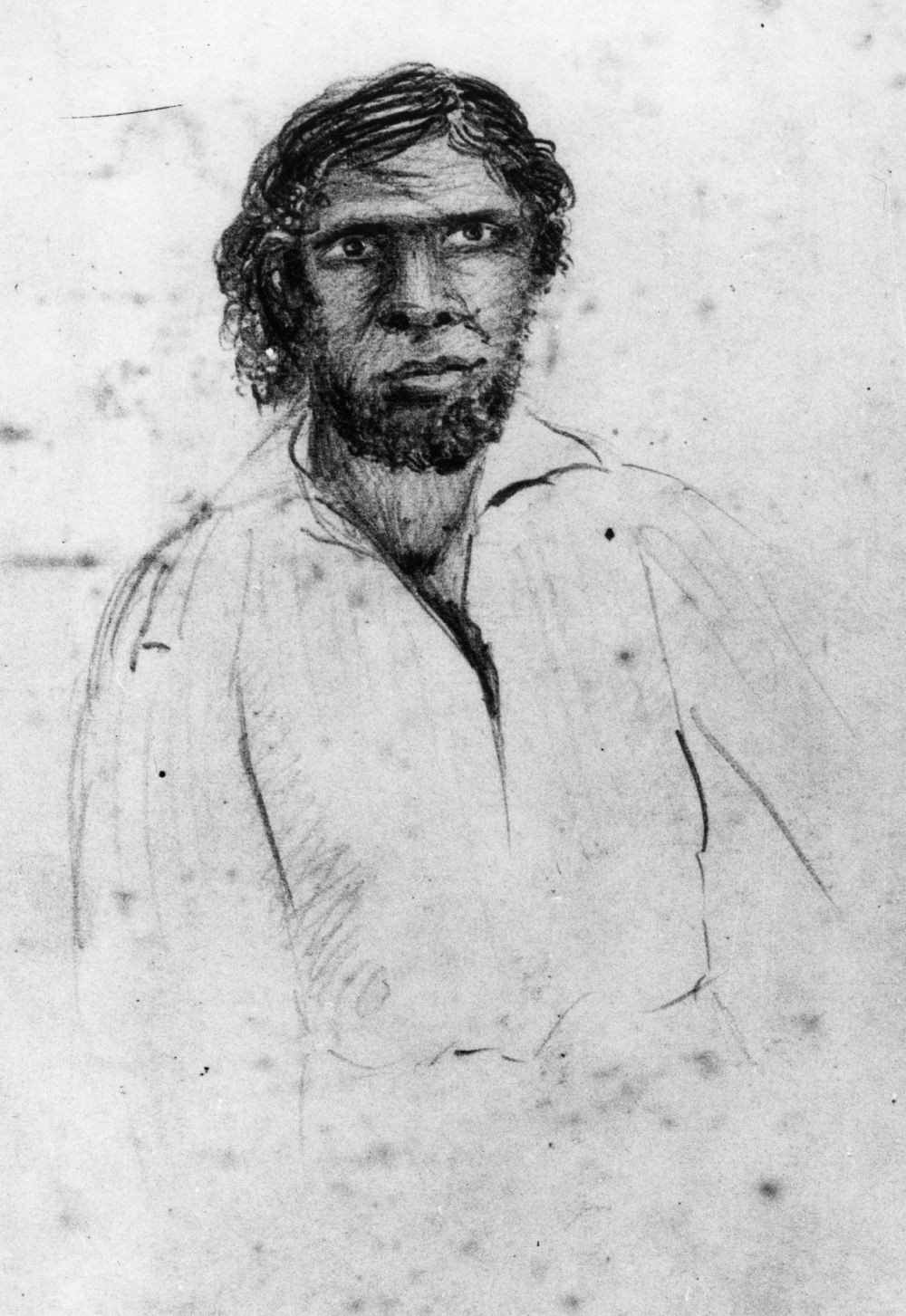

James Davis “Duramboi.”

James Davis (1808-1889) was a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside a forbidding, taciturn man.

A blacksmith’s son from Glasgow, James Davis was convicted as a teenager of “theft, habit and repute” (a thief who associates with other thieves) in 1824 and transported to New South Wales on the Minstrel.

He was sent to Moreton Bay in February 1829 for a robbery at Patrick’s Plains, and absconded from the settlement after six weeks.

Returning convicts told the authorities about several “wild white men” living with the indigenous people of South-East Queensland, but, officially, nothing more was heard of Davis until May 1842.

An exploration party led by Andrew Petrie had gone to the Wide Bay district, and had encountered David Bracewell (“Wandi”), a serial absconder with a tale to tell of another white man in the region – James “Duramboi” Davis.

After some negotiations (very theatrically retold by expedition member Henry Stuart Russell), Davis returned to Brisbane Town in June 1842. He worked as a bush constable and tracker, then set up at Kangaroo Point as a blacksmith.

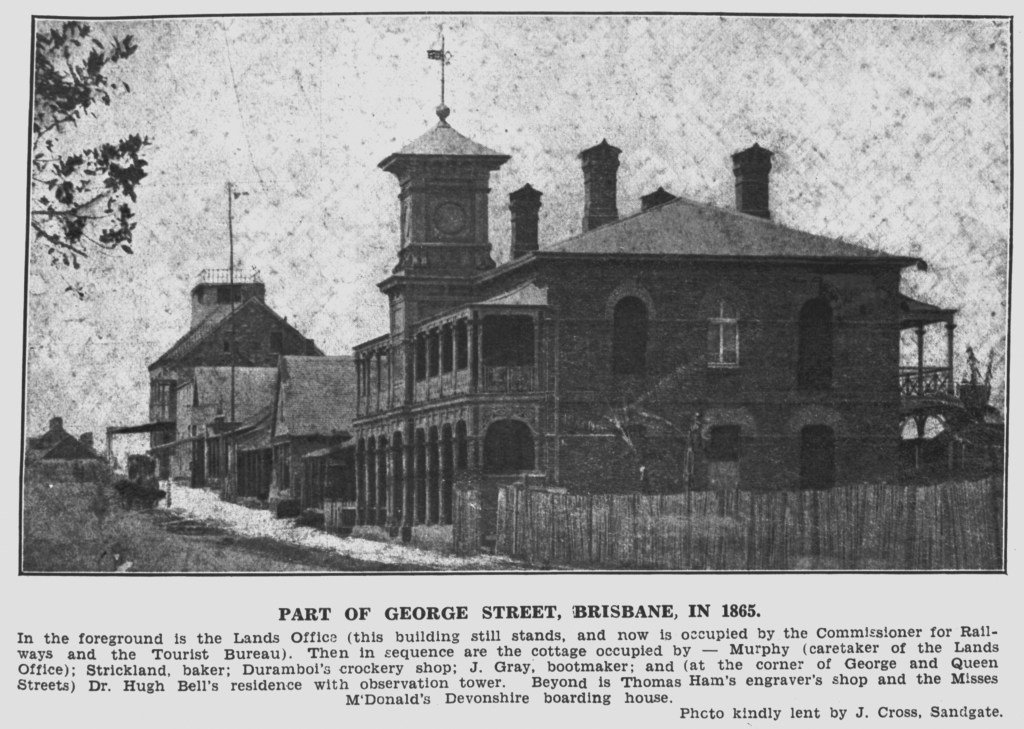

In 1847, Davis married Annie O’Shea and later moved his smithy to George Street, Brisbane. He began to be employed as an Aboriginal language interpreter in the Courts in the 1850s – something he would do for 30 years.

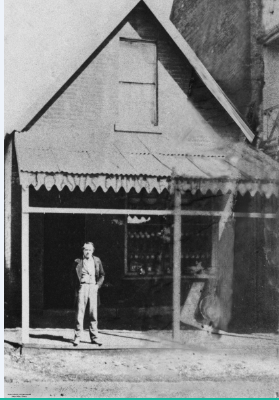

Retiring from his forge, Davis became a merchant, specialising in glass and chinaware. Following Anne Davis’ death, he married Bridget Hayes. He died in 1889, leaving a considerable estate, mostly bequeathed to the Catholic church and the Brisbane Hospital.

Those are just the bare facts of his life. James Davis reluctantly gave one account of his time with the indigenous people north of Brisbane. He said that he had been adopted by an indigenous family due to his resemblance to their dead son, Duramboi. He gave an account of the customs and beliefs of his former community to an inquiry, yielding as little information as he possibly could. He was known to order curiosity-seekers from his shop if they tried to pry into his time in the bush.

James Davis had at least one child with an indigenous woman – James “Jimmy” Davis. Jimmy lived with Davis and Anne in their Burnett Lane house in the 1860s, and attended the National School in Brisbane. Jimmy was prone to running away, finally deserting his father’s home due to his treatment at the hands of his step-mother. (Who was no doubt displeased at the presence of the teenage boy in her house when she’d been married to Davis for over 20 years. Ahem.)

Davis had no children with his European wives. It seems that both ladies had strong, argumentative personalities and a fondness for drink. Both women fought with Davis, their neighbours, and the law.

As Davies grew older and frailer, he became estranged from Bridget, and added a codicil to his will that gave the bulk of his estate to the church and hospital. At some point in early 1889, he returned to the marital home – probably too frail to look after himself anymore – and Bridget physically and verbally chastised him about his penny-pinching in the household budget. Davis had to be rescued by neighbours, and Bridget was arrested. Duramboi died as a result of his frail health and injuries. Bridget was tried and acquitted of his manslaughter in July 1889.

His son, “Jimmy” Davis, long estranged from his father, spent decades working in the Pine River and at Kilcoy as a timber-getter. Charles Perry wrote to Archibald Meston in 1918 about Jimmy’s movements, and suggested that Meston locate and interview the son of Duramboi before it was too late. This does not appear to have occurred, possibly due to Meston’s distaste for James Davis senior, who he found to be a very common, uneducated little man. Jimmy passed away in the 1920s.

My piece on the return of Duramboi to Brisbane is linked here.

My Convict Runaways piece on Duramboi is linked here.

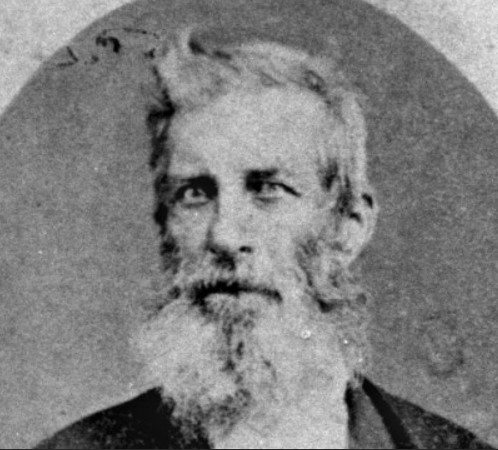

Thomas Dowse, “Old Tom.”

Hackney-born Thomas Dowse (1809-1885) was a teenaged messenger boy in London when an act of foolishness caused his life to take a dramatic turn. Thomas made off with some clothes from his brother and gave them to an acquaintance to pawn. The result, at the Old Bailey, was “guilty-death-aged 15.” Fortunately, this was respited, and young Tom was transported to New South Wales for life.

In Sydney, Thomas Dowse kept his head down and worked hard. He was a quick learner and moderate commercial success followed. He married and started a family, eventually earning a pardon in 1839.

Tom’s knack for commerce and his boundless enthusiasm led him to try his luck when Moreton Bay opened up in 1842. After a memorably bad first night, a cold and hungry Dowse was taken in by kind Sydney acquaintances, and never looked back. He saw the need for cross-river travel and bought a skiff. He noticed the rising and falling fortunes of fellow-colonists, and put his business skills to use by becoming an auctioneer. He had little opposition to start with, and his friendly nature and sales ability made him a very successful local entrepreneur.

Dowse was a driving force behind Separation, stood for the abolition of transportation and corporal punishment, and served as Brisbane Town Clerk from 1862-1869. He returned to commerce, and died in 1885 after a long, full life.

His series of articles, “Old Times,” writing as “Old Tom,” brought the distant past to vivid life. He knew the great and the good. He enjoyed all of his sojourns around the colony, and wrote memorably of them. His optimism and enthusiasm is endearing to the modern reader – he had none of the pomposity of other memoirists.

Old Tom’s Reminiscences is linked here.

The Corner, in which Old Tom revisits some lively characters is linked here.

Dundalli.

From the little we know about his life, Dundalli (c. 1820-1855) seems to have been a leader in his society from an early age. We first encounter him in 1841, when he met with Mr Hartlestein, who was part of the German Mission to the indigenous people of Moreton Bay. Indeed, Hartlestein’s diary quotes Dundalli (then aged about 20) as saying, “Now we see you are missionaries, and no liars. You have come as you promised.” Dundalli then negotiated a form of co-existence with the Germans.

This meeting occurred in August 1841, before free settlement. The only European people Dundalli was likely to have encountered before that meeting would have been convict absconders and their pursuers. “No liars” seemed to be important to Dundalli and his people, and the presence of a small group of helpful German missionaries was something that could be endured.

The following year, a different group of Europeans began to intrude. Selectors and squatters, armed of course, accompanied by servants and bullock teams, began to clear vast swathes of country. Few of these settlers were willing to negotiate co-existence. More and more of them came. Homelands and hunting grounds were taken over by force. Members of Dundalli’s family, his community, friends and acquaintances, were driven away or killed.

As the 1840s progressed, the name Dundalli became linked with a series of anti-European activities and attacks. (Dundalli wasn’t even mentioned in early reports of the Gregor and Shannon murders.) It hardly seemed to matter whether Dundalli was involved or not. He was a strikingly tall and charismatic indigenous man, associated with indigenous resistance. Therefore he was a villain in the eyes of settlers.

In 1854, Dundalli was captured and tried for the murders of Andrew Gregor in 1846 and William Boller in 1847. In January 1855, Dundalli was publicly hanged in front of the Brisbane Gaol in Queen Street, an act intended as a warning to local aboriginal resistance leaders. There were indeed groups of indigenous people watching from the hilly ground near Wickham Terrace. What they saw was a display of barbarity of the European kind, as the hangman botched the execution, and had to pull down on Dundalli’s legs to effect his death by strangulation.

There would be never be a public execution in Queensland again. Dundalli was the last person to be publicly executed. He was not the last indigenous man to be executed.

Sources:

- Research already documented in linked articles (please, don’t make me type it all out again!).

- The Colonial Observer (Sydney, NSW: 1841-1844), Thursday 28 October 1841, page 27.

- The Australian Dictionary of Biography entries, particularly Libby Connors’ biography of Dundalli.

- All illustrations, unless otherwise credited are from the State Library of Queensland’s digital collections and are out of copyright.