The Visit of the Duke of Edinburgh.

His Royal Highness paid a visit to the Colony of Queensland. We fed him, feted him and sang at him. With varying levels of success, although HRH was unfailingly polite. At least no-one tried to assassinate him…

Original post here: https://moretonbayandmore.com/2022/02/26/the-grub-train-and-the-emu-hunt-that-never-was/

George Edmondstone.

George Edmondstone (1809-1883) was a founding father of Brisbane . He was one of the very first free European settlers in Brisbane, and opened a butcher’s shop in Queen Street. He was a businessman, alderman, the Mayor of Brisbane, and a member of both the Queensland Legislative Assembly and the Legislative Council. Not all at the same time, though. That would have been quite exhausting.

Edmondstone championed all sorts of sensible and beneficial things for Brisbane – the Breakfast Creek Bridge, Enoggera Reservoir, Toowong Cemetery, and the Brisbane Central School.

Edmondstone was by repute a genial and kindly Scottish gentleman. Sadly, he’s less memorable than some of his contemporaries – he was not given to bouts of florid oration, horsewhipping his rivals, scurrilous letters to the Editor, or tottering about the Legislative Assembly in his cups.

Elections.

Ugh. Politics – so toxic. Parties vying to stir up the social, racial and ethnic prejudices of the public? Check. Misinformation and disinformation? Check. A lack of civility in public discourse? Check. All of these elements were present in the North Brisbane election of May 1888.

On the big night, the footpaths of Queen Street were crowded with people watching the results as they came in to the Courier office, “on a large screen, illuminated by electric light.” Sounds very modern.

Left: Sir Thomas McIlwraith, the victor. Right: Sir Samuel Griffith, the runner-up. Politics in 1888 was a job for the hirsute and knighted.

After more than a month of political coverage – from the quite reasonable (The Courier, The Telegraph), to the quite unreasonable (The Figaro, who demanded to know “Who Gave the Chinese their Votes?”), emotions were running high. Sir Thomas was carried off to the Australian Hotel in triumph, Sir Samuel (viewed as dangerously not anti-Chinese) was booed and someone tried to poke him with a stick.

In Albert Street, a mob of drunks decided that they would ask the Chinese who had given them their votes by throwing stones at their windows and roofs. Crowd estimates varied wildly between 150 and 2000. Fortunately, the mob did not follow through on its threat to take on the Breakfast Creek Temple (probably because it was too far to walk), and dispersed.

Electric Light.

It was slow in coming, but the reception it received was priceless.

Here’s my original post: https://moretonbayandmore.com/2024/04/09/let-there-be-electric-light/.

Brisbane Town had a fascination with Edison and his creations. Here’s Edison Lane, and some Edison artifacts dug up on the Queen’s Wharf site.

Jane Ellis.

Isabella McEvoy was an orphan kept as a servant by Jane Ellis, the wife of a prison guard at Brisbane. Jane Ellis treated her harshly, but when the ill-treatment escalated to starvation, violence and humiliation, Isabella had to run away.

Here’s what happened: https://moretonbayandmore.com/2020/09/30/the-most-despised-woman-in-old-brisbane-town/

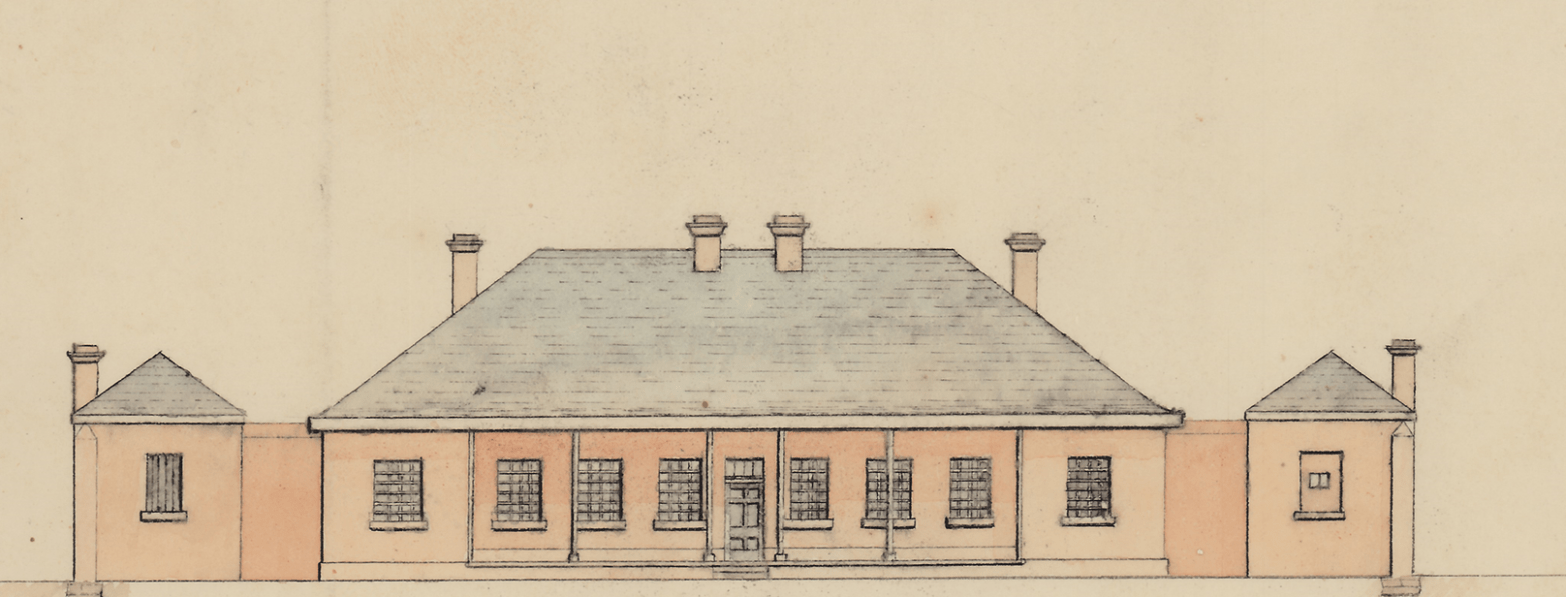

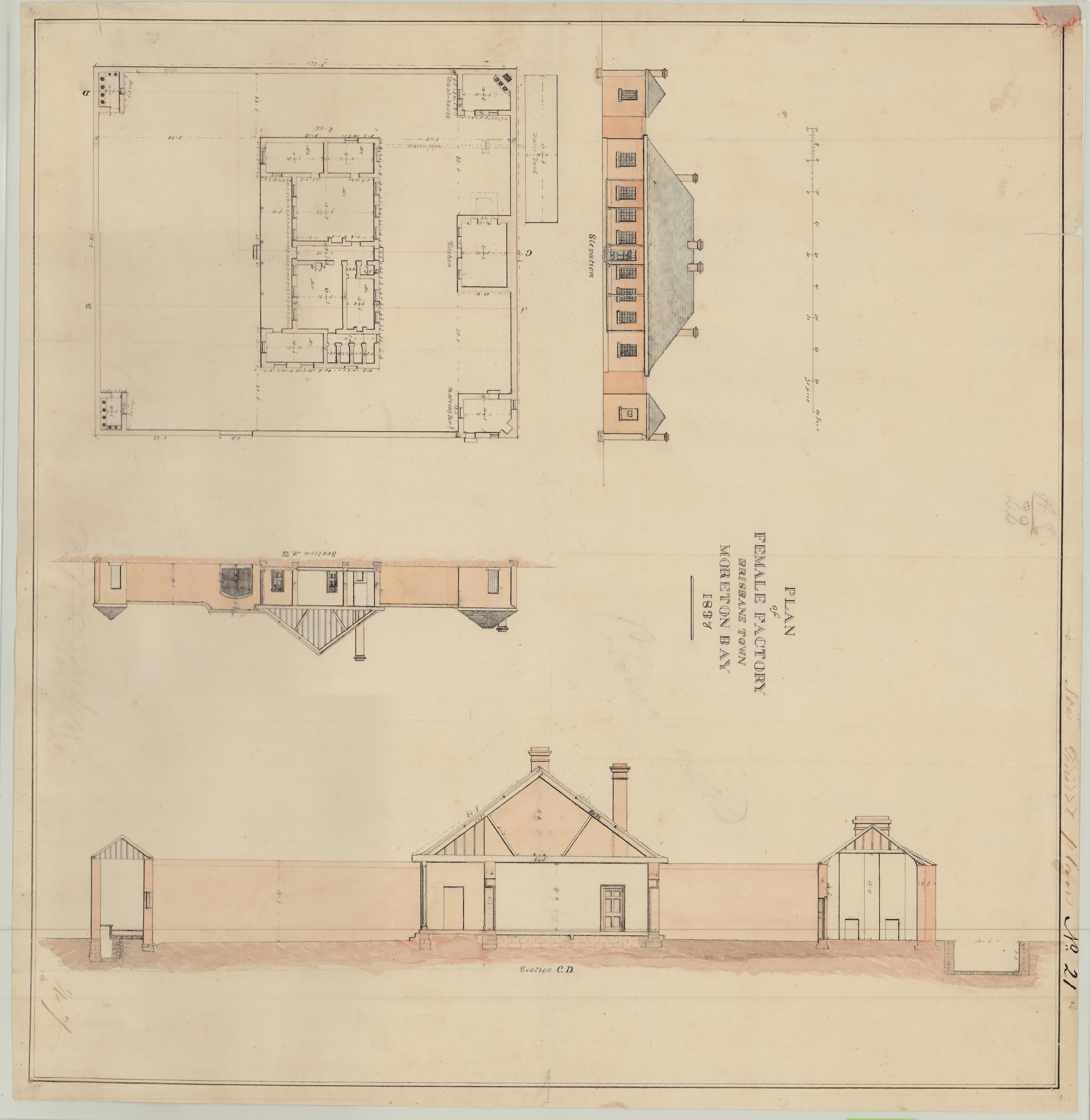

Two views of plans for the Female Factory, which became the Brisbane Gaol, where the Ellis family was employed in the early 1850s. And AI has provided a suitably unhappy-looking Victorian orphan.

Executions.

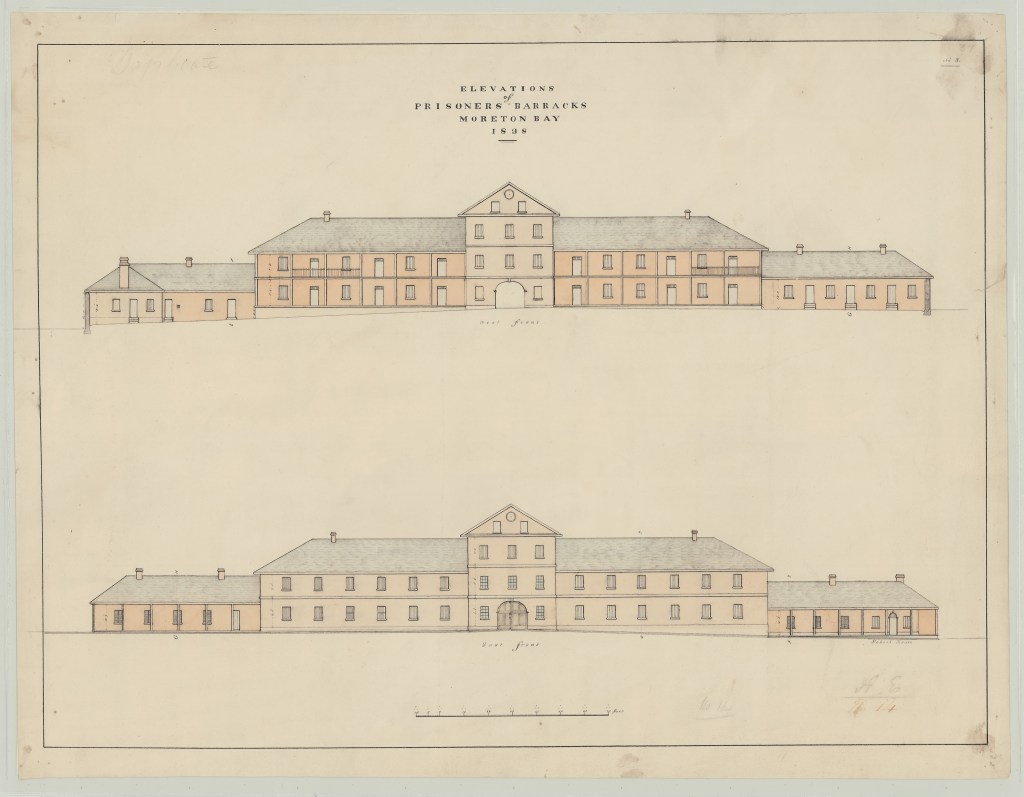

Executions were mercifully rare in the earliest days of the colony. Until 1850, Brisbane town had no Supreme Court, scaffold, or executioner. The earliest hangings were enacted as a spectacle to warn others – those of Charles Fagan and John Bulbridge at the Convict Barracks in December 1830, and those of Mullen and Ningavil at the Windmill in July 1841. The former were repeat absconders who committed depredations on the run, and the latter were convicted of involvement in the murders of surveyor Stapylton and a convict labourer named Tuck. The prisoners were tried in Sydney, and they, their executioner and the scaffold equipment had to be transported by sea to Moreton Bay in order to carry out the sentences.

After 1850, convictions and executions took place in Moreton Bay, and after Separation in 1859, at various gaols across the colony. The last public execution was that of Dundalli, whose protracted hanging was such a horrible spectacle that the practice was moved out of sight.

There were 94 people executed between 1830 and 1913 in Queensland. One was a woman, the vast majority were indigenous men. Capital punishment was abolished in 1922.

The Experiment.

In June 1846, the Courier published its first edition, and the Experiment steamer began a regular passenger and cargo service on the river between Brisbane and Ipswich. The Courier was invited along on the VIP maiden voyage:

THE “EXPERIMENT.”—This steamer started from North Brisbane, on her experimental trip to Ipswich, on Wednesday morning last. Mr. Pearce, the owner, and a select party on board, were warmly greeted as they passed up the river, by a large concourse of spectators, who had assembled to witness her departure. Owing to the imperfect knowledge of the person acting as pilot, respecting the river flats, she got aground near the crossing place at Woogaroo, and was detained until daylight the following morning, when she proceeded on her voyage, and reached her destination at one o’clock.

Moreton Bay Courier, June 20, 1846

That grounding on the first journey to Ipswich was a sign of things to come. In early January 1848, the Experiment foundered and sank at Queen’s Wharf during bad weather. It took Mr Pearce’s business prospects with it. He sold his remaining interest in it to Boyland and Reid, who managed, after two months of trying, to raise the steamer from its silty grave. After a lot of repairs, Experiment worked the river until September 1849, when it was scrapped.

Still, Experiment’s nearly four years of service brought Brisbane and Ipswich together, socially and physically, and spared many colonists a jolting cart journey over rough roads.