Agnes Conner Chilton Ferguson (and, unofficially and occasionally, Walmsley) stood only 5 feet 1 ¼ inches, but she was more than capable of intimidating husbands, neighbours and two generations of the Brisbane constabulary. Her criminal activities, fuelled by a liquor intake that would have felled a lesser being, ranged from assault to trickery to public nudity. At one point, her husband traded her to another man for a horse and cart. The other man wanted his horse and cart back very quickly.

The Princess in disguise.

She was born around 1815 in Cork. She claimed to be the daughter of a Colonel of the 88th Regiment but was an unemployed farm servant when she conned the kind, but incredibly gullible, Cott family of Middleton in 1839. Agnes had been parading about the district wearing a sign that read, “Take pity on the Deaf and Dumb.” The Cotts did just that and let her stay at their house for a bit.

During her stay, Agnes communicated with the daughter of the house by writing on the bellows, confiding that she was in fact “a princess in disguise,” wealthy beyond imagination, a close confidant of Queen Victoria, and under a vow of silence for seven years to a Daniel O’Connell. She was also on a pilgrimage of some sort. The young Cott daughter was entranced by the tale and took some money and clothes and joined the silent, disguised princess on her journey. That pilgrimage took them to Cork City, and some “haunts of vice,” that Miss Cott sensibly fled from, but not before being relieved of her luggage and money.

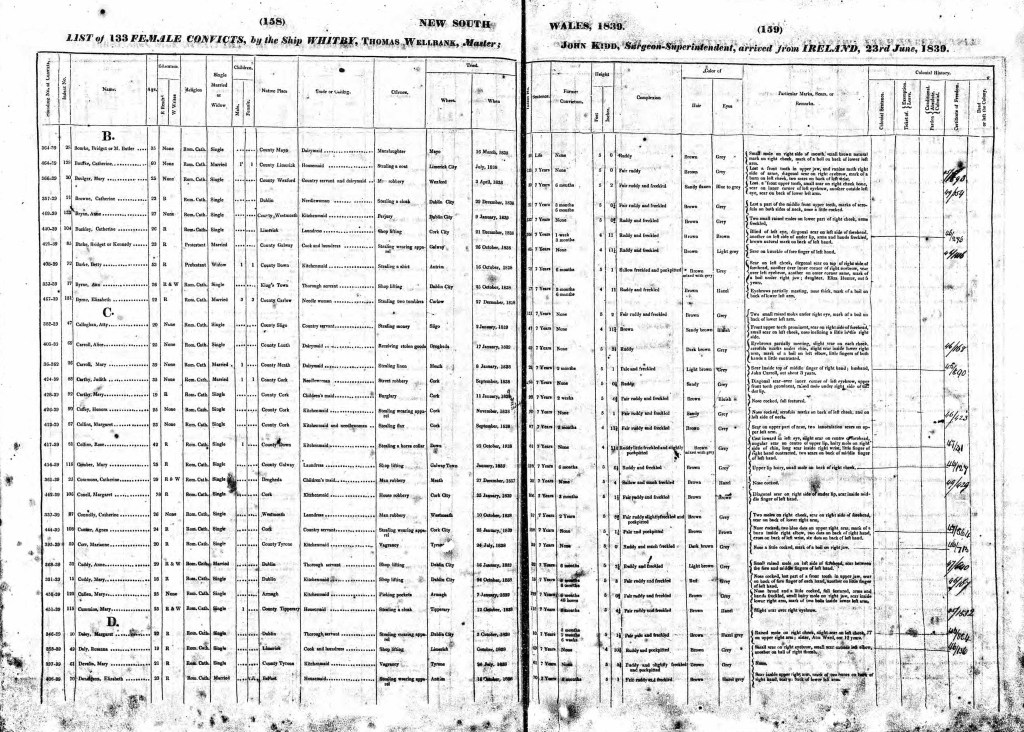

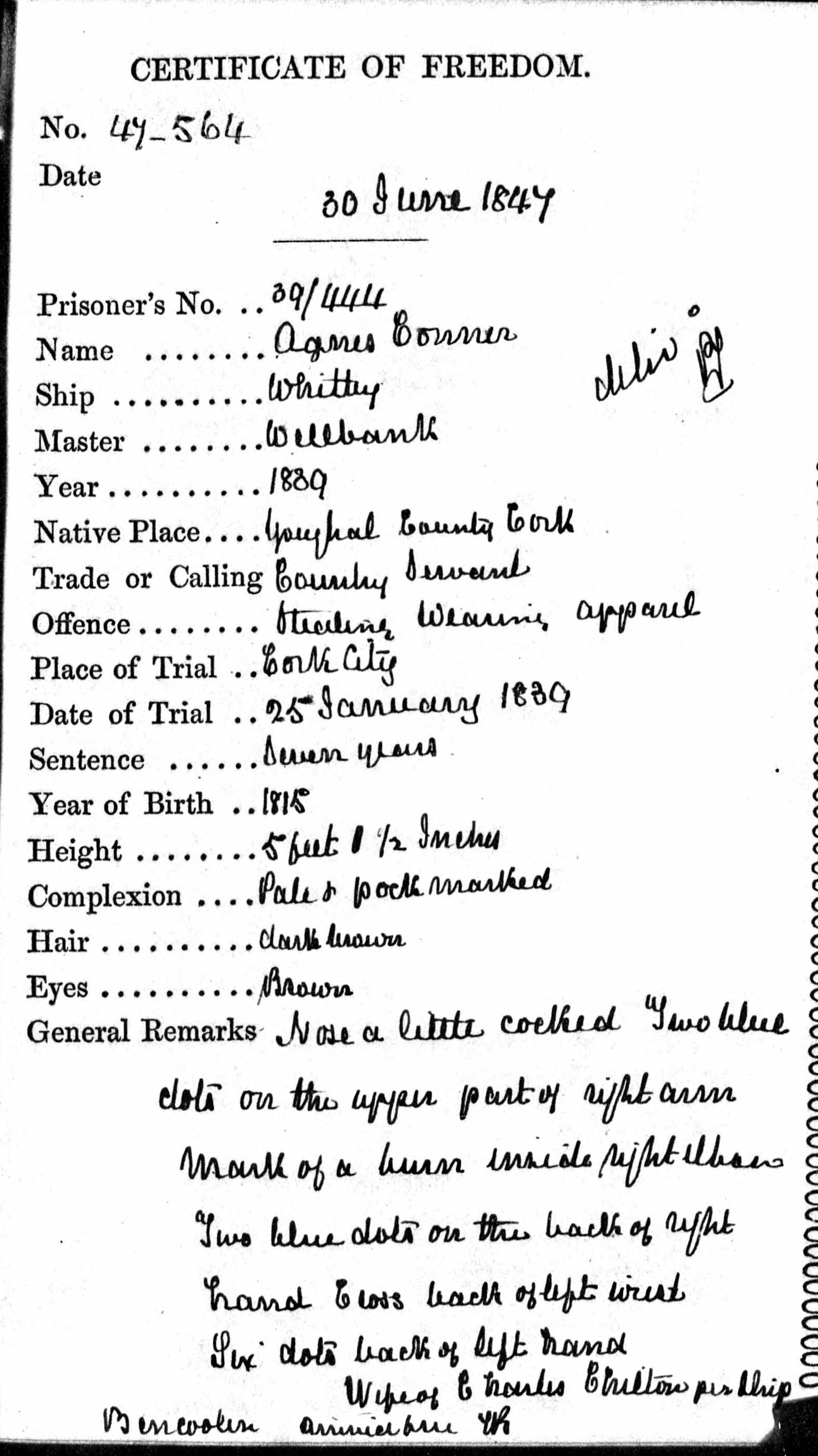

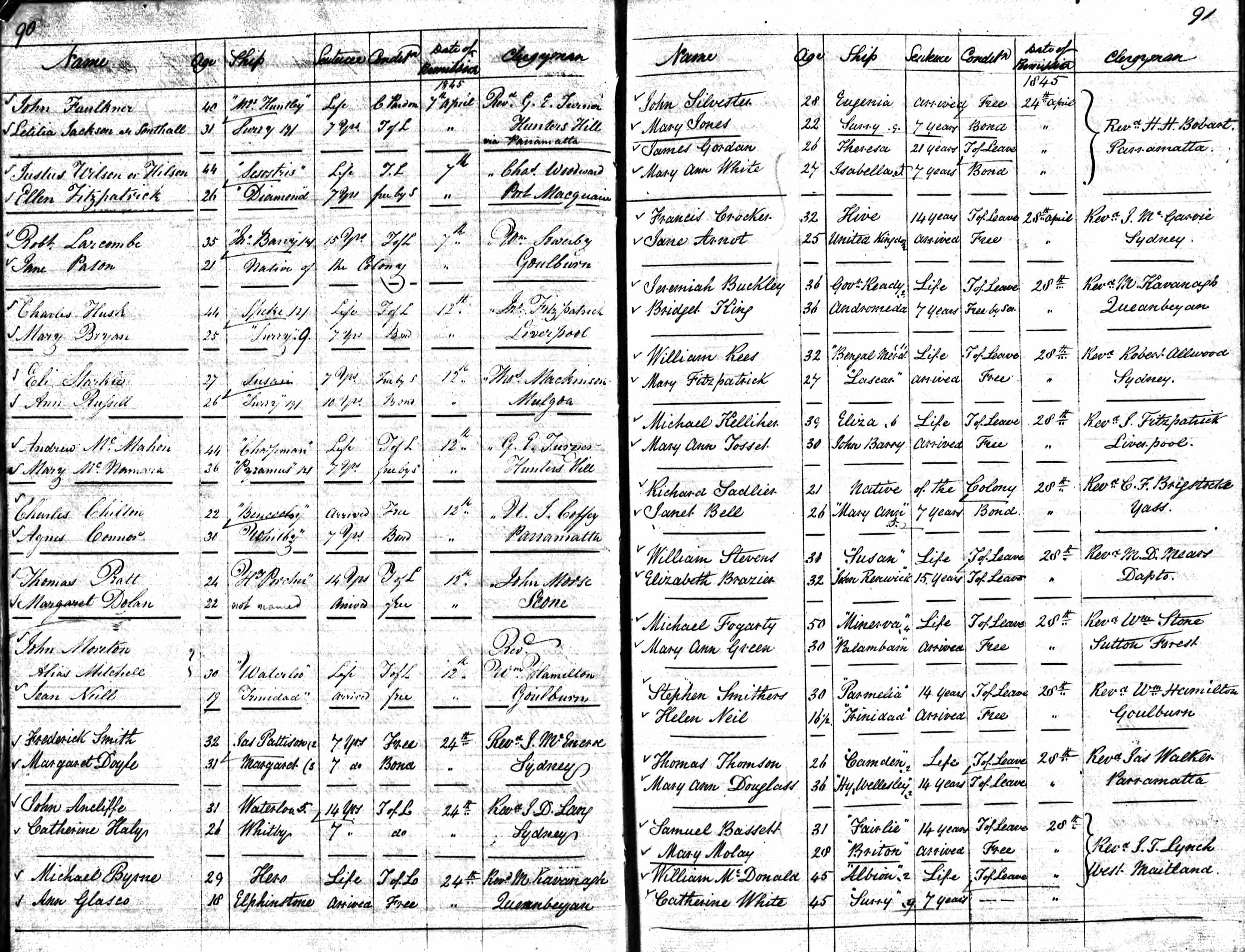

Agnes Conner was found guilty of stealing clothes and transported to New South Wales on the Whitby in 1839. The indents of the ship record her as 24 years of age, pale and slightly pockmarked, with brown hair and eyes, a cocked nose, and a tattoo of a cross on the inside of her left wrist. [i] She was sent to Parramatta to work as an assigned servant.

The convict bride.

In 1845, Agnes successfully applied for permission to marry, and became the bride of one Charles Chilton, aged 22, who had arrived free on the Bencoolen. (The eight-year age gap must not have concerned Mr Chilton.)

The ink had barely dried on the marriage licence when Agnes, proud of her improved social status as a married woman, and also rather drunk, lingered in Sydney to see a play rather than return to her assigned service. Her employer had her charged with absenting herself, and she spent seven days in the cells at Parramatta, pondering the complexities of her situation.

The following year, Charles Chilton junior was born at Sydney, and in 1847, Agnes had served her sentence and received a Certificate of Freedom, which noted that she was the wife of Charles Chilton, who had arrived free by the Bencoolen. A free immigrant husband was a social cachet not many convict women could boast. What became of Charles Chilton senior is puzzling,[ii] although a person of that name was charged in 1859 with escaping from the police (and was noted as having arrived per “Bencooling”).

A bride again.

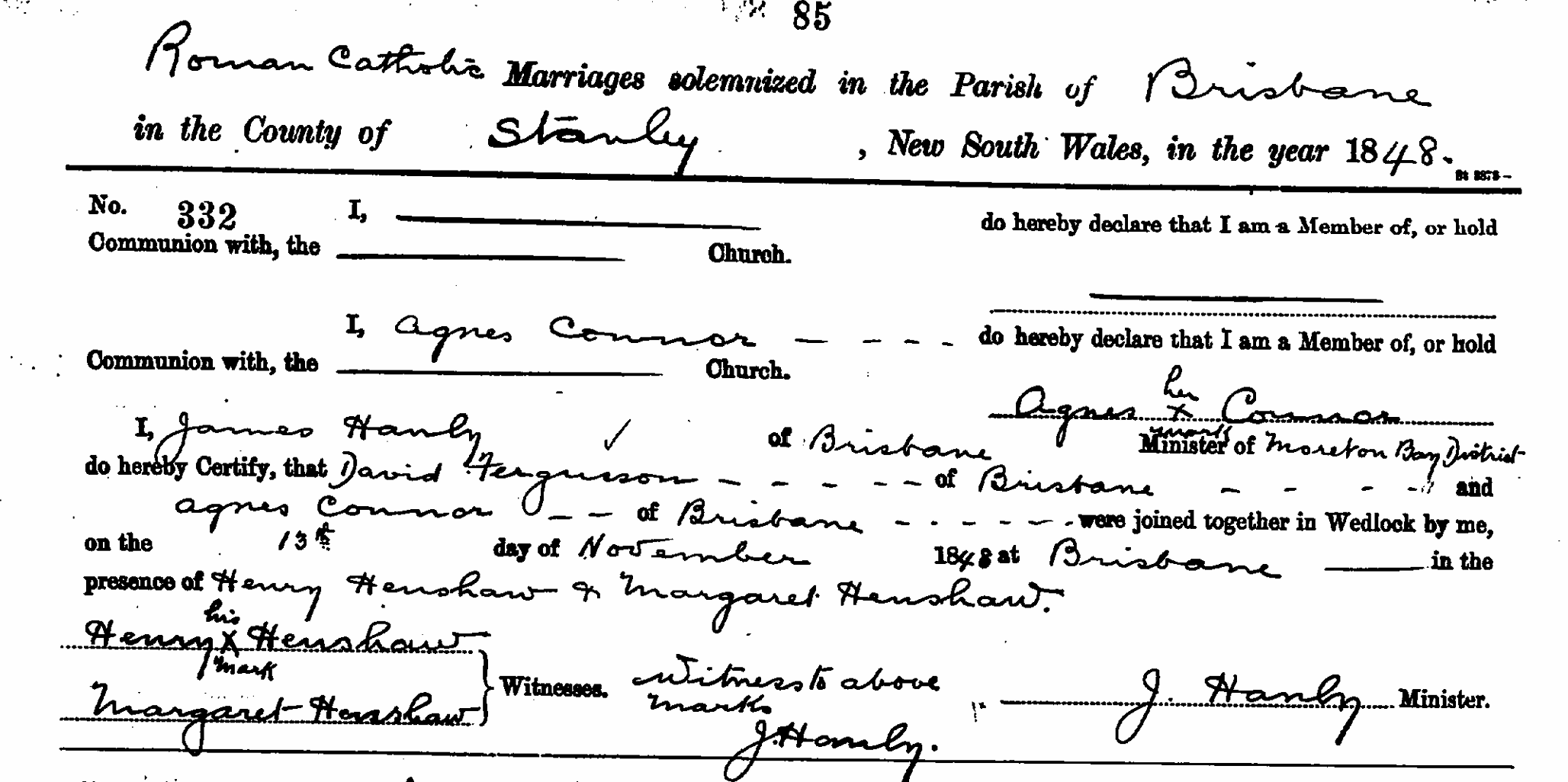

At any rate, Miss Agnes Conner, as she called herself, was married to David Ferguson by the Reverend Hanly at Brisbane Town on 13 November 1848. David Ferguson was a ticket of leave man, having been convicted of highway robbery at Norfolk in 1834, and sentenced to transportation for the term of his natural life. He had been born in 1810, making him five years older than Agnes. There were no children from this marriage, and David informally adopted Charles junior, who was known as Charles Ferguson until he reached adulthood.

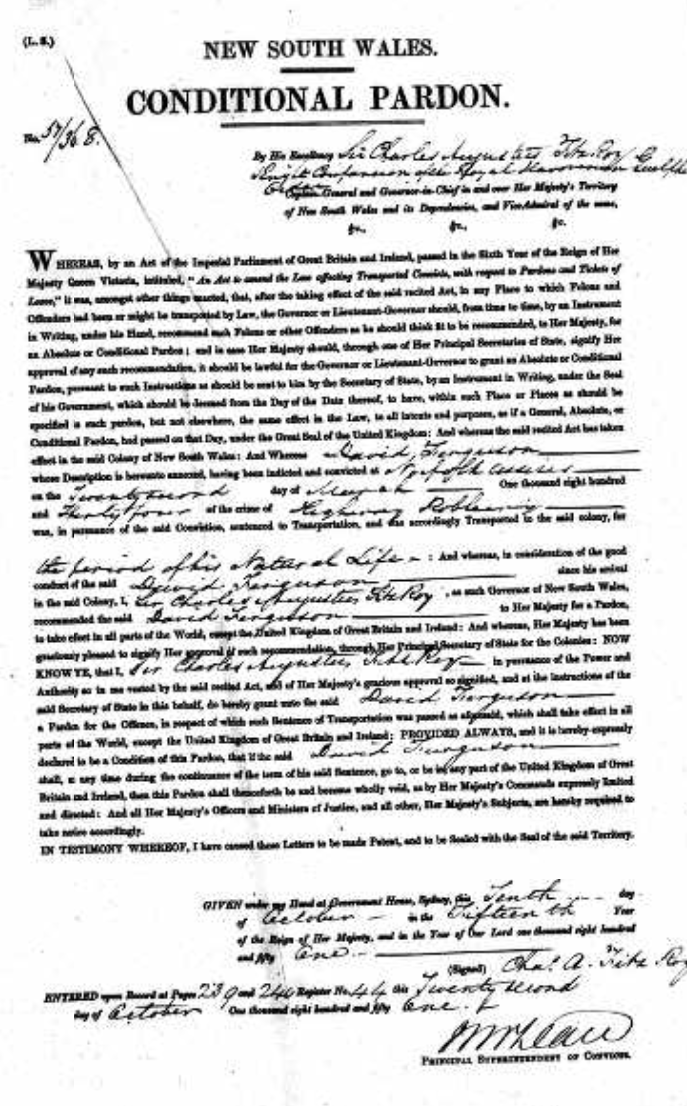

David Ferguson, although prone to a drink or two, was a quieter person than his wife, having once been warned that he could lose his ticket of leave when he turned up on the drunk list. He took Captain Wickham’s advice and earned a Conditional Pardon in 1851. He worked as a labourer and timber-getter around Brisbane and later, the Pine River.

Raising Hell.

Mrs Agnes Ferguson, meanwhile, raised Hell. In early 1849, she barged into the house of Charles Whitmore whilst drunk and destroyed some property. She had done this to him before, “having apparently an irresistible inclination to visit and annoy him when she was in her cups.[iii]” She was fined 20 shillings.

In 1851, Agnes was living at Kangaroo Point, with Mrs Catherine Driscoll, known locally as “Cranky Kate.” On 20 March, Agnes was the one who was cranky. She had, in the words of the Courier, “had been indulging in vinous fluids to a considerable extent, and reeled home to Kangaroo Point in a state of the most exalted independence.” When Mrs Driscoll opened the door to her, she was punched and throttled with her own hair. Mrs Driscoll screamed. Constable John Conroy heard the scream and came to the rescue.

Agnes turned her attention to him, punching him in the mouth and tearing at his hair and clothing. The only holding cells in the former convict colony were in North Brisbane, meaning that Agnes had to be taken across the river by ferry to be locked up. This proved to be quite a challenge. On arriving at the ferry, Agnes roared, “You bugger, I’ll drown you as well as myself,” and tried to jump in the water. Constable Conroy prevented this and managed to hustle her into the craft. As they were crossing, she broke loose and threw herself into the river, nearly drowning. Conroy rescued her at the cost of most of his uniform and lodged her in the lock-up.

The following morning, Captain Wickham convicted her in the following terms:

The Bench require Agnes Ferguson to find sureties to keep the peace (by her husband in £10 and two sureties in £5 each) towards Catherine Driscoll and all Her Majesty’s liege people for six calendar months, and in default of such sureties to be imprisoned in the common gaol at Brisbane for six calendar months.

Her Majesty’s liege people were safe for the next fortnight, as David Ferguson struggled to obtain the £10[iv] and two other sureties to release Agnes from durance vile. She left Brisbane Gaol on 5 April 1851, and her behaviour there had been orderly, probably because no alcoholic beverages had been served.

Two years passed quietly, at least as far as the law was concerned. Then, in January 1853, Agnes and a man named John Murray[v] were arrested for gross public indecency, and sentenced to pay a £10 fine each, or to spend three calendar months in gaol. David Ferguson, perhaps understandably, did not pay his wife’s fine this time, and both parties stewed in custody until mid-March.

Agnes celebrated her release from gaol by getting very drunk and using profane language in the streets. She found herself facing Captain Wickham once again. This time, David Ferguson appeared in Court and begged the Bench for leniency, promising that his wife was about to leave town on the Brothers. A relieved Wickham chided Agnes and fined her 10 shillings, which David paid.

If Agnes did leave town, she didn’t stay away long. The following year, Agnes took a neighbour named Margaret Banton to court, accusing her of threats. Despite the scepticism of just about everyone, Agnes insisted that she felt quite threatened, and a bond was imposed on Mrs Banton. Perhaps Agnes had almost learned her lesson, because she managed only two more arrests in the 1850s, on both occasions for being drunk and using profane language in public.

The wife, the horse and cart, and the dog.

The Fergusons had been married for twelve years in 1860. David was 50, Agnes 45, and Charles (Chilton) Ferguson was thirteen. Agnes hadn’t been arrested in over two years. The family might have seemed to be settling down. But the Fergusons weren’t quite ready for that.

In March, following a complaint by David Ferguson, Constable Thompson arrested one Aaron Walmsley and charged him with the larceny of three holland jackets, one blue handkerchief and a dog. Aaron Walmsley was arrested whilst camping at Red Jacket Swamp (later Gregory Park, Milton). Walmsley also had in his, er, possession one rather willing Agnes Ferguson, who claimed ownership of the clothing and pet. The Bench dismissed the charges against Walmsley.

In June 1860, the newspaper reading public in Brisbane Town were treated to the spectacle of David Ferguson being summoned by Aaron Walmsley for illegally detaining his horse and cart. Mr Ferguson’s defence, borne out by a violently misspelled document, was that he had obtained the horse and cart from Walmsley in exchange for Agnes. Both parties, at the time, considered it a fair exchange, and Agnes was apparently quite willing to go with Walmsley. After a few months in her rather wayward company, Walmsley regretted the deal, and wanted his horse and cart back, please.

Agnes Ferguson, not to be outdone, charged Aaron Walmsley with violently assaulting her with a tomahawk to the arm and a knife to the neck. She attempted to show her wounds to the Magistrates, who, after viewing one forearm, would not permit her to remove any further garments. Agnes did not want Walmsley punished, she said, just bound over to keep the peace towards her. Faced with the husband, the horse and cart, the “contract,” and the alleged assault, the Bench dismissed all the cases and admonished the parties about their behaviour.

The following night, Agnes was parading around George Street, very drunk indeed, and in a state of near nudity. Aaron Walmsley paid her 10 shilling fine, rather than have her spend 48 hours in the cells. He then had to pay a further 5 shilling fine, because she was arrested the next night for drunkenness (but not indecent exposure, thankfully).

The accident.

While all this was going on, Charles Chilton Ferguson, her only child, suffered an injury that could have claimed his life. In April, Charles was riding in a bullock dray when he had an accident, and his left leg was crushed against a tree. He was admitted to the Brisbane Hospital as an urgent case, and his injury was assessed as so severe that his leg was to be amputated at the knee “at daylight, or sooner if necessary.” The boy was weak and pale, having lost a lot of blood. On April 5, Dr Bell performed the amputation, successfully. Mercifully, Charles was given chloroform for the operation.

On 7 June 1860, the same day his mother and stepfather were making a spectacle of themselves in court over the horse and cart contract, Charles was fitted with a wooden leg. The day Agnes was staggering about drunk and near nude, her teenaged son was discharged from the hospital with his new leg. While Agnes was living with Aaron Walmsley, it seems that her son did not live with the couple.

In August 1860, Agnes and Aaron were brought before the magistrates in Brisbane again, this time for a brutal assault on an old man at The Gap[vi]. John Dunford had allowed Walmsley and Agnes to stay at his place for a time but asked them to leave after a particularly drunken incident. Agnes flew at Dunford, knocked him down and kicked him. Walmsley beat the man about the head with a stick. Both were imprisoned.

In October, Agnes came to town to seek treatment at the hospital, but “a glass or two” of alcohol caused her to lose control of her language in public. She repeated the offence in March 1861, and then went to live with Walmsley in the bush. She managed to stay out of trouble for three years and possibly tried not to drink too much as she approached her fifties.

In May 1864, Agnes returned to Brisbane and made such a nuisance of herself at a drinking establishment that two constables half her age couldn’t get her to the lock-up. Eventually, a horsedrawn cab was hired, and Agnes (by now rather stout) was with difficulty crammed into it, and taken to the watchhouse. She spent seven days in gaol for being unable to pay the fine and restitution for the cab fare.

That seems to have put an end to Agnes’ rambunctious career, at least as far as the Courts and Brisbane Gaol were concerned.

The Benevolent Asylum.

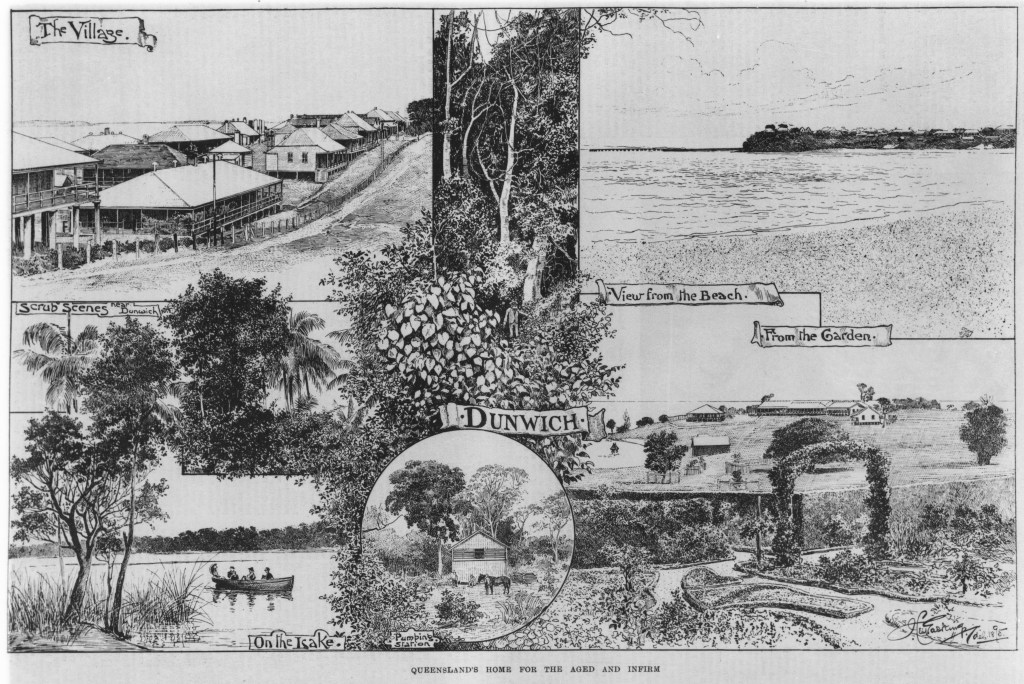

In November 1887, David and Agnes Ferguson were admitted to the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum, aged 76 and 67 respectively. David had a bad back and “senile decay,” while Agnes had a broken shoulder bone. They were living at South Pine, eking out a living on Charles’ farm, having reconciled as old age loomed.

Agnes remained at Dunwich until her death aged 78 in 1893. David Ferguson came and went from Dunwich over the years, going on leave in April 1897. He died on 22 May 1897, at the age of 87. Dunwich, having not heard from him since his departure in April, struck him off the register as being absent beyond his leave in August, later amending their entry to “reported dead.” Aaron Walmsley had passed away in 1890.

Charles Chilton married in 1870, raised a large family and bore a sound character all his life, which is something of an achievement, considering the environment in which he was raised. He died in 1919, much mourned by his many loved ones.

[i] Agnes got off lightly in the indent descriptions. Other ladies on board had facial scars, scrofula marks and hairy moles and upper lips described in humiliating detail

[ii] A Charles Chilton passed away in Brisbane Hospital on 28 December 1884, but according to the statistics of the hospital published in the Courier, that Charles Chilton was a 20-year-old schoolteacher.

[iii] Moreton Bay Courier (Brisbane, Qld.: 1846 – 1861), Saturday 17 February 1849, page 2.

[iv] David Ferguson could probably expect to earn between £22 and £30 in a year, according to the information at the Institute of Australian Culture, Wages in Australia.

[v] A waterman who held a ticket-of-leave, and who lived a rather itinerant life about the colony.

[vi] “a place which, according to Mr. Brown’s expressed opinion on the Bench, bears a very bad repute and requires purification,” according to the Courier.

Documents: 1. Convict Indent, 1839. 2. Certificate of Freedom for Agnes Conner. 3. Application to Marry Charles Chilton. 4. Marriage in Brisbane to David. 5. David’s conditional pardon.