She went by many names, but the nickname “Ellen the Cutter” was the one that the press and public remembered best. How she came by that nickname was never explained but it seems to have been in common use in Ipswich when she first came to the attention of the constables in the early 1850s.

She married three times, bore five children, and was imprisoned in Queensland under many names and on many occasions from 1851 to her death in 1876. A man was killed over her affections, she ran a house of ill repute, she hurled sausages at local merchants, and was known for nicking people’s washing. She must have been a lot.

Part 1 – Miss Sweeney/Mrs Semple.

Ellen Sweeney.

Two young Irish servants named Ellen Sweeney arrived in Sydney, Australia as assisted immigrants on board the ship Forth in 1841. One was 22, born in Clonmel, able to read, and a kitchen maid. The other was 16, born in Galway, unable to read or write, and a nurse maid.[i]

The Ellen Sweeney who made such regular visits to the Brisbane and Toowoomba prisons gave her birth year as 1823 or 1825. According to her third marriage certificate, her parents were James Sweeney (shoemaker) and Julia Slattery, and she came from Tipperary. She may have been the 22-year-old Ellen on the Forth.

Ellen stood 5 feet 3 inches and had brown hair and grey eyes. She seems to have been very attractive in her youth, with journalists in the early 1850s describing her as “fair Ellen.” (By 1865, she was described by the Brisbane Gaol Admissions Book, rather unkindly, as stout and sallow.)

In the early 1840s, Ellen met and married an Irish ticket of leave man named David Semphill, whose name was usually recorded as Semple[ii]. David was more than 10 years Ellen’s senior but might have been an attractive prospect for Ellen. He had light brown hair, hazel eyes, a slightly crooked nose and freckled complexion.

David was serving a sentence of transportation for life for a robbery he committed as a 20-year-old in 1831. He was known to be a quiet individual and a hard-working man. Even after a spot of absconding early in his sentence, his employer, a Mr Kemmis at Bathurst, took him back. David earned a ticket of leave to Bathurst in 1841, which was amended to Moreton Bay in September 1842, making him part of the first wave of new arrivals after the convict settlement closed.

Ellen Semple.

The Semples lived at Ipswich, and had three sons – James, William and David Jr [iii]. In June 1845, David had his ticket of leave amended again, to allow him to travel to the Darling Downs to work for Mr Thomas Alford, who was setting up as a storekeeper and publican at Drayton.

Ellen was at the time pregnant with James and might not have made the journey west and across the range to Drayton. If she didn’t, she would have to wait and hope for a share of his wages, an experience that left many wives in that situation to suffer uncertainty and poverty.

William was born at Ipswich in 1849, and by 1850, Ellen was living on and off with a young sawyer named Thomas Young. Neither party was discreet about the relationship.

“I’ll knock dandrum out of you!”

By early January 1851, Ellen had returned to live with her husband. At 9 in the morning of Saturday 11 January 1851, a drunk and angry Thomas Young decided to confront the Semples. He made his way down towards David Semple’s house and started shouting taunts. When Semple came to the door with his wife Ellen, Thomas Young yelled, “Come out and I’ll knock the dandrum [iv] out of you. I’ll burst the bloody eye in your head.”

A neighbour of Semple’s, Thomas Stanley, heard Young make a boast about how well he knew Ellen Semple. (The boast was deemed too disgusting to print.) Young threw his hat on the ground and rolled up his shirtsleeves. In Ipswich in 1851, that was the universal signal for a challenge to fisticuffs.

John William, a shepherd staying nearby, joined a group of locals who had assembled on some sleepers to watch the fight. The fight didn’t seem to be happening, and the crowd started to leave, disappointed. Just as they turned away, Young turned back towards Semple, they exchanged blows, and the two men fell. Semple got back up and went inside his house, with a long clover knife in his hand. Young was bleeding heavily from a wound in his side.

Witnesses helped Young, who was still conscious and able to speak, indoors. The police were called; so was a doctor. Young told John William, “Nobody injured me,” when it was quite clear that someone had. William Vowles told Young that it was his own fault. “I know it is,” replied Young, “I blame nobody for it but myself.” When Vowles found out that Semple had done it, he said, “I told you that would be the case three or four months ago.” Young, who was bleeding heavily, agreed. He died soon after.

David Semple told the Chief Constable, “I stabbed him. Any person with a Christian feeling would have done the same.” He was charged with wilful murder.

The Semple Trials.

As David sat in Brisbane Gaol, awaiting his date with the Supreme Court in May, Ellen had to feed her children and make a living by herself. Now a well-known and disgraced woman, that didn’t leave her many legal options.

Ellen didn’t enhance her standing with police and her community by getting involved with Joseph Lyons and Thomas Phillip. These men were described as “flash gentry” by the Courier and were engaged in some spurious financial transactions.

Joseph Lyons, who sported a “beard moustache,” passed himself off to a credulous out-of-towner as local worthy John Gammie, and swindled a saddle out of the visitor. Thomas Phillips had Ellen pass a cheque allegedly drawn by another Darling Downs identity, Joshua Bell. Ellen said she might get a dress and some flour from the transaction.

Both swindlers were easily discovered and charged. Ellen, after a brisk examination by the magistrates was given her “PPC card. [v]” The newspapers made it clear that Thomas Phillips was fair Ellen’s new swain, and the Bench wanted to know if Mr Phillips was living with her. Ellen averred that she was not a “boarding-housekeeper,” but instead took in washing and sewing to support her family. Ellen’s evidence was sufficient to cast doubt over Phillips’ knowledge of the forgery of the cheque, and he was discharged.

When David Semple was brought to trial in May 1851 at the Brisbane Assizes, Ellen was not called upon to give evidence. Her relationships outside of the marriage, as well as her involvement in the “flash gentry” transactions made her an undesirable witness.

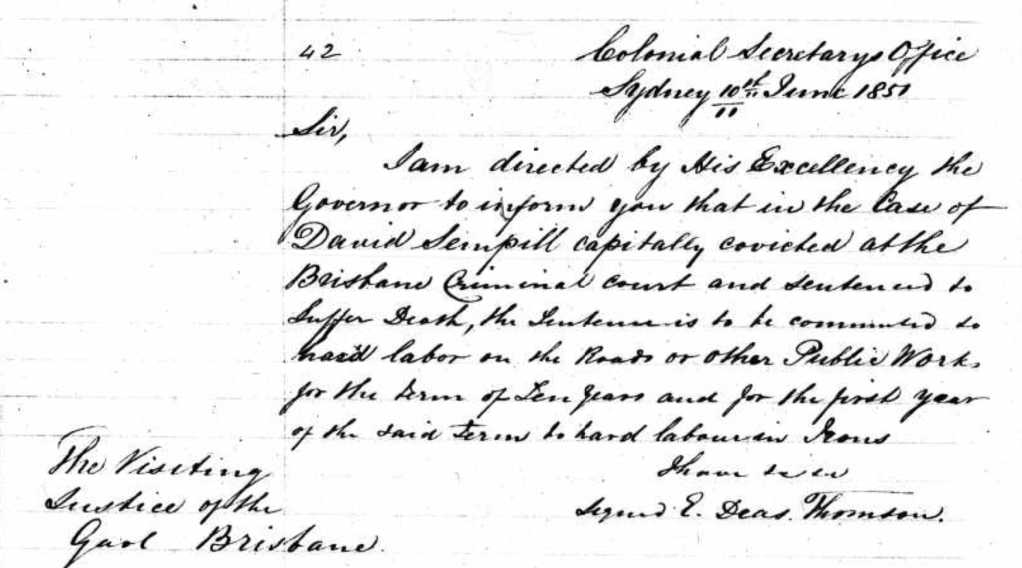

David was found guilty of murder, and sentenced to death. The jury strongly recommended that he be spared execution, due to the provocation that he had received. David Semple spent a no doubt long and tortuous month in Brisbane Gaol, awaiting the decision of the Governor in Sydney.

On June 11, a brief letter was sent to Moreton Bay, advising that the sentence had been commuted to 10 years of hard labour on the roads and public works of the colony, the first year to be spent labouring in irons. David was sent to Sydney, placed in Darlinghurst Gaol, and then sent to Cockatoo Island to serve his time.

A woman alone in the world.

Ellen Semple was on her own, with three young sons. She had no prospect of seeing her husband for the next decade.

On 29 October 1851, Mrs Ann Golbert returned home to find that someone had taken some of her property. Mrs Golbert had a good idea of who might be responsible and proceeded to Ellen’s house. Ellen refused to return the property, and the police intervened. Part of the property stolen from Mrs Golbert was a visite [vi] that Sarah Hammond had left with her. Ellen didn’t help her case by threatening to stab Mrs Golbert “as David did Tom Young.” When the case reached the Brisbane courts for trial, Ellen was found guilty of stealing from both women, and was sentenced to six calendar months in prison, with hard labour.

Ellen emerged from Brisbane Gaol on 15 May 1852. She had been an orderly prisoner. Four days later, her name came up in the news again. A man was robbed of a money order at her house, which was described as “a place of ill-repute in the township.” Ellen wasn’t involved in the theft.

For six years, “the cutter” was quiet. What happened to Ellen, not to mention her children, in the years after her release in 1852 became clear in 1858. In May 1858, she was charged with robbing one William Morley, a carrier, of £70 in cheques and cash.

The evidence showed that Ellen had been living with Morley for seven years as his wife and had taken his name. The relationship ended in catastrophe on 17 May 1858, when Ellen fled from Morley’s camp outside of town in the middle of the night, seeking refuge with the Hunter family. Ellen was in her underclothes and barefoot. She said that Morley had been beating her. She begged the Hunters to go back with her, fearful that Morley might murder her children. It was too dark for the Hunters to set out for Morley but let Ellen shelter with them for the night.

When dawn broke, Morley sent for the police and charged Ellen with stealing his papers. Morley’s evidence was contradictory, and Ellen escaped conviction because of it. (Mr Macalister, a future Premier, conducted the prosecution, and was decidedly unhappy with the result. He ordered the depositions, with a view to an appeal.)

Ellen was free, but her relationship with Morley was over (he died several months after the break-up). A familiar figure came into view at just the right time. David Semple, on early release after eight years, and with a ticket of leave to report to the Ipswich Bench, arrived back in town.

Coming up – Ellen Morris/Ellen Clinch and a racehorse named Carbine.

[i] There was no certification of baptism registry entry in either case.

[ii] David Semphill couldn’t read or write, and the spelling “Semple” stuck.

[iii] James was born in November 1845 at Moreton Bay, William’s year of birth is listed as 1849 on his gravestone, and David Jr’s record cannot be located at present.

[iv] Derived from a Scottish dialect, a dandrum is a whim or a fancy.

[v] To go at liberty, to be called on as a prosecution witness.

[vi] A cape or mantle, worn as an outer garment. As if Victorian women didn’t have enough clothing to contend with, the visite was something one could pop on top of all of the other layers, for going-out. Two ladies at right model their visites, no doubt rather more ornate garments than the one Ellen swiped in Ipswich in 1851.

2 Comments