James Hamilton was trouble. A tough labouring man with a penchant for stealing horses, and the kind of fellow who would make life very difficult for any police officer sent to arrest him.

Ipswich Chief Constable Edward Quinn had few men to spare when a warrant for Hamilton’s arrest arrived at his station. He chose Constable William Devine, a sterling character, as the man who would have to single-handedly capture James Hamilton. The fugitive was known to be working at Fernielaw, a station near Ipswich. Quinn warned Devine that Hamilton would try to escape – he was “one of the greatest scamps about the place.”

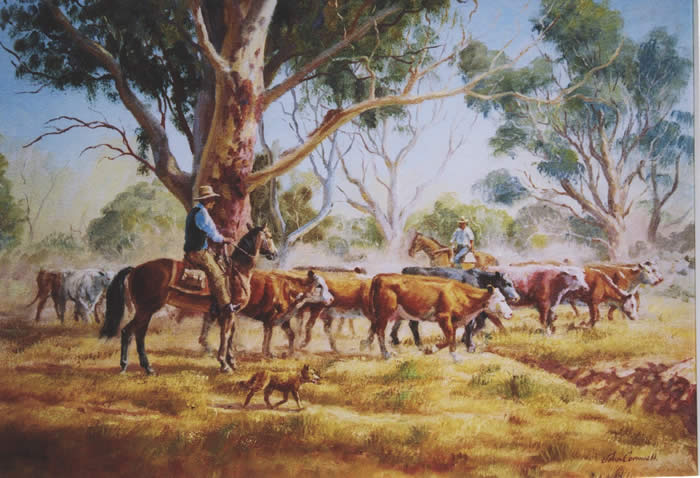

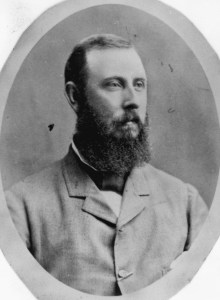

Armed with a warrant and a pistol, Constable Devine arrived at Fernielaw on 18 September 1857. He met with station owner Francis North, and initially had little trouble locating the accused, and bringing him in to see North.

Then, a hesitancy set in. Devine asked Francis North if he thought it would be alright to let James Hamilton stay with his family that night and set off for Ipswich the next morning. North told him, in effect, “You’re the policeman. You decide.”

After a no doubt uncomfortable night handcuffed to Hamilton in the man’s tent, Devine briefly removed the cuffs so that his prisoner could get dressed. As luck would have it, just as Hamilton was tending to his britches, Devine had a “visitation of God” as he put it, experiencing a sudden bout of dizziness and a nosebleed. When God left him, so had his prisoner.

Devine pursued Hamilton until he found the man on a small island in the river. He mustered up some resolve, and told Hamilton to surrender or he would shoot. Hamilton replied, “I won’t surrender – I will allow you to shoot me first, as there are about twenty charges against me besides the charge upon which you arrested me.” He would rather die, he declared, than serve his life in gaol.

Devine fired at the prisoner, who appeared to take a shot between the shoulders, and then fell into the water.

Devine then reported to Francis North that his prisoner had (a) escaped, and (b) been shot and fallen into the river. Could Mr North spare him some powder and ball? And some help possibly? A posse from the station, made up of North, Devine and four farmhands started out for the river. There was no sign of Hamilton.

Devine then had to survive the wrath of Mrs Hamilton, who threatened him because he shot her husband. That was probably nothing compared to the wrath of the Chief Constable.

Francis North had his men drag the river with poles the following day, and a local indigenous man pointed out some footprints on the bank. North couldn’t make them out, because the gravel on the ground was packed hard.

William Devine was charged and committed for trial for suffering a prisoner to escape. He was found guilty at the October 1857 Supreme Court sittings at Brisbane. The jury asked the judge to be lenient in the light of Devine’s previous excellent character. Devine was fined £10 and paid up immediately. He left the police force and eventually became a publican.

“I think you are over-doing your duty”

Nothing further was heard of James Hamilton. Until September 1869, when Devine noticed a very familiar man on the streets of Ipswich. He had the distinctive scar over one eye that had made Hamilton so memorable.

When Constable William Gunn arrested James Hamilton for escaping from custody twelve years earlier, he was haughty. “You will have to take me to New South Wales; I think you are over-doing your duty;” whilst in the watch-house prisoner said, “Escaping from the police was no crime thirteen years ago-it has only been made a crime since separation.” Which of course wasn’t true – a prisoner at the 1857 assizes was tried for that crime immediately after William Devine parted with his £10 for allowing Hamilton to escape.

Hamilton had survived, swum to the other riverbank, and had kept a low profile for a dozen years. His confidence grew to the point that he openly lived in Ipswich by the late 1860s. It turned out to be hard to nail Hamilton for escaping so spectacularly all those years ago – no-one seemed to know where the original arrest warrant had been filed.

The authorities in Sydney, Brisbane and Ipswich had been canvassed, but no-one could locate it. James Hamilton had retained a rising lawyer named Charles Chubb to protest the constant adjournments and non-production of evidence. Eventually, the Crown had to give up and offered no true bill at the December 1869 Assizes.

The Attorney-General couldn’t prove that James Hamilton had escaped lawful custody because he couldn’t prove that there was a reason for him to be in custody in the first place.