Highway Robbery at Kangaroo Point

Samuel Fletcher loved horses. To be precise, he loved horses that weren’t his own. A horse was an expensive proposition – why pay for one?

That was Samuel’s mindset back when he was a lad in Nottingham – he worked as a groom[i], and was surrounded by fine horses all day. The temptation was too great.

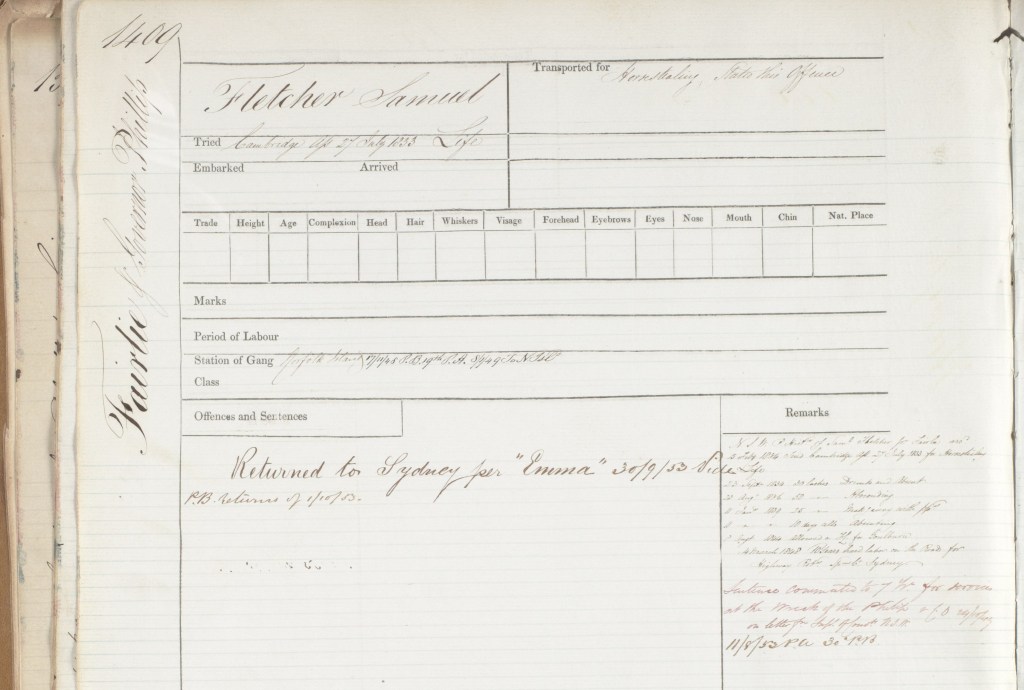

Acting on that impulse earned Samuel a lifetime’s stay in Australia via the Fairlie, where his turbulent nature drove him to abscond from his employers in Goulburn and Yass, before he was awarded a ticket of leave in 1844 to remain in the district of Goulburn.

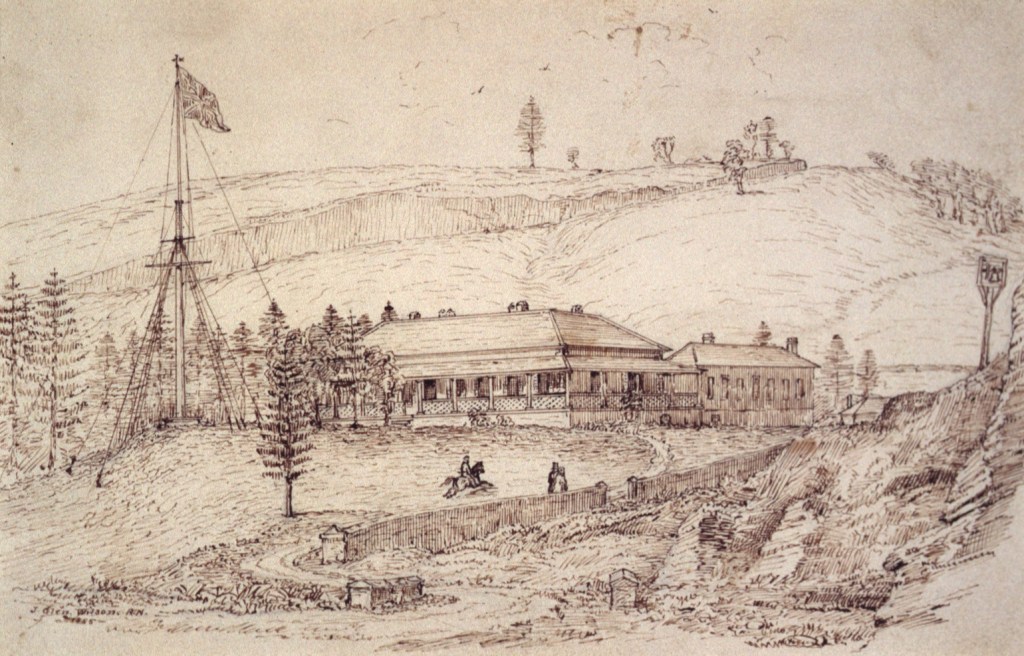

Samuel was in the district of Moreton Bay for the New Year in 1848. On 3 January, Samuel had a gun, a vendetta to settle, and no horse.

At South Brisbane, he saw the man who had wronged him, working on an allotment. He’d settle the scoundrel. Samuel fired his pistol at the man but missed, and the man retreated into his hut with Samuel in hot pursuit. His nemesis, through a crack in his door, asked Samuel what he’d done to offend him.

Samuel roared, “If it’s fifty years’ time, I will take your life.” That’s about when he realised that he was talking to a chap called Michael Slavin, not the man he meant to murder. He apologised and went away.

As the sun was starting to set. Samuel Fletcher saw a man on horseback near Kangaroo Point. The fellow tied up his horse, went into the surveyor’s tents and asked for a cup of tea. Samuel lingered about the tents, walking back and forth, admiring the horse.

The men in the tent were watching, so Samuel went away for a moment. No. The horse was his. He put his foot in the stirrup, and addressed the incredulous surveyors, “This is my horse.” The man who’d rode up earlier replied, “If he is, I have paid for him,” and tried to get the reins.

Samuel reached into his coat and produced his pistol, telling the man, “By the eternal Jesus, I will blow your brains out if you don’t let the horse go.”

The man backed off and decided to walk home, with Samuel following him on his horse. Samuel was now in need of funds and thought that this fellow might have some to give him. He told the man to stop walking and hand over his cash. The man said he had none. Samuel told him to prove it by stripping off. The man declined, saying that Samuel could search him without making him undress.

Samuel had an idea. “Do you see that tree there?” he said. ” I will leave your horse there some time in the night, and I will see if you are game to come for him.” And with that rather cryptic threat, Samuel turned and rode off.

Frederick Smith, the unfortunate horseless and cashless man, hurried homewards and alerted the police.

Constable Murphy joined Smith at the surveyor’s tents in pursuit of the horse thief. It didn’t take long for them to find Samuel, still on the horse, in company with two other riders. Smith told Murphy which horse was his, and Samuel, hearing his voice, turned and fired directly at Murphy and Smith. The shot whistled by the constable’s head, but neither man was hurt.

Smith’s stolen horse, however, was startled by the gunfire and nearly unseated Samuel. Murphy secured Samuel Fletcher before he could regain control of the frightened animal. Fletcher appeared “stupid from the effects of drinking.”

The two horsemen who’d been on the road with Samuel were eternally grateful for Smith and Murphy’s takedown of Fletcher – he’d been in the process of robbing them when the law arrived.

Samuel Fletcher said nothing in his defence when he appeared at the Police Office, and was committed to take his trial in Sydney, where he continued to offer no explanation or defence. He was found guilty, and the judge sentenced him to ten years’ hard labour on the roads. His Honour was so perturbed by the crime, and Fletcher’s behaviour, that he suggested an assessment of the prisoner’s state of mind.

After he was deemed fit to serve his sentence, Fletcher was ordered to be sent to Norfolk Island on the Governor Phillip, via Van Diemen’s Land.

On 24 October 1848, the Governor Phillip struck a reef off Gull Island, in the Furneaux group to the north of Tasmania, and was wrecked. The brig had been carrying passengers, soldiers and convicts (who were locked in the hold). Of the 85 people on board, 16 were either drowned or killed by debris.

The survivors camped on Gull Island “subsisting on penguins and shellfish” for nearly a fortnight. Samuel Fletcher was one of the survivors, and his good behaviour and service in the crisis proved so valuable that the Governor reduced his sentence to seven years. Once recovered and fed, he was sent off to Norfolk Island to do the rest of his time.

In 1853, Samuel Fletcher completed his sentence and was returned – uneventfully – to the mainland. The following year, he was discharged from the employ of a family at Black Creek, in the Maitland district. Not taking too kindly to his dismissal, Samuel returned to the Fletcher house and made threats and behaved so violently that the local constable had to keep watch over the family all night (there was no police lock-up in town). During the night, Fletcher got his handcuffs off twice and managed to stab the hand of one of his captors.

The Maitland bench returned him to Government. He made a short tour of Newcastle and Darlinghurst Gaols, before being lodged in Carter’s Barracks. He escaped from Carter’s Barracks in March 1855, taking a saddle and bridle with him. Presumably no horse was available.

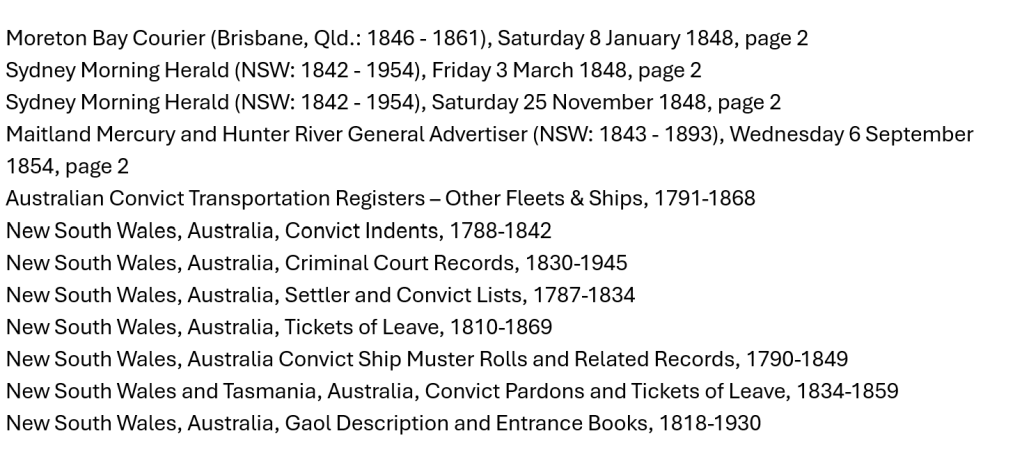

[i] He was also an “indifferent” watchmaker, according to his convict indent.