Board of Inquiry

Above – left to right: the Board who heard Frank Bowerman’s charges. Left: Auditor-General Frederick Orme Darvall, Surveyor-General Sir Augustus Charles Gregory, Collector of Customs William Thornton.

The official Board of Inquiry into three charges of misconduct against Frank Sydney Bowerman was convened with a speed modern public servants would find astonishing. The Colonial Secretary’s Office wrote to the Auditor-General on 30 October 1868, ordering a Board to be assembled, and by 04 November 1868, the Board had examined Bowerman and several other public servants, and produced a record of proceedings, decision and recommendation.

The first charge was failing to submit to the Treasury the Billiard License fee of £10 received from “one Ford,” the second was an identical charge regarding Dalby publican Alfred Gayler, and the third was for having paid a Police Constable’s salary by his own private cheque in opposition to positive instructions. (Never mind that it bounced, apparently.)

Bowerman, who had taken a room at the Royal Hotel in Brisbane after being sent the show cause letter, acquitted himself superbly before the Board. No doubt he was under tremendous personal stress, but his willingness to admit his fault through carelessness impressed the Board. Excuses were made, but they were convincing enough.

Having carefully weighed the several excuses offered by Mr Bowerman, and the absence of any attempt at concealment, the Board, while leaning on him most severely for his culpable negligence, are inclined to acquit him of a deliberate intention to defraud and venture to express a hope that the Executive will, in consideration of his length of Service, and of the general laxity in conducting business, which has hitherto been too prevalent among the Country benches, and without which Mr Bowerman’s omissions must have been at once discovered, deal as leniently with him as circumstances will permit, and inflict some punishment short of absolute dismissal.

Members cannot overlook the charges of gross negligence against Mr Bowerman but taking into consideration the recommendation of the Civil Services Board , and the long services of Mr Bowerman, recommend that instead of dismissal from the public service (which under the circumstances they almost consider it their duty) to advise Mr Bowerman should be suspended from the Commission of the Peace, deprived of the Office of Police Magistrate at Leyburn and seconded to Nanango as Clerk of Petty Sessions.

Decision of the Board of Inquiry.

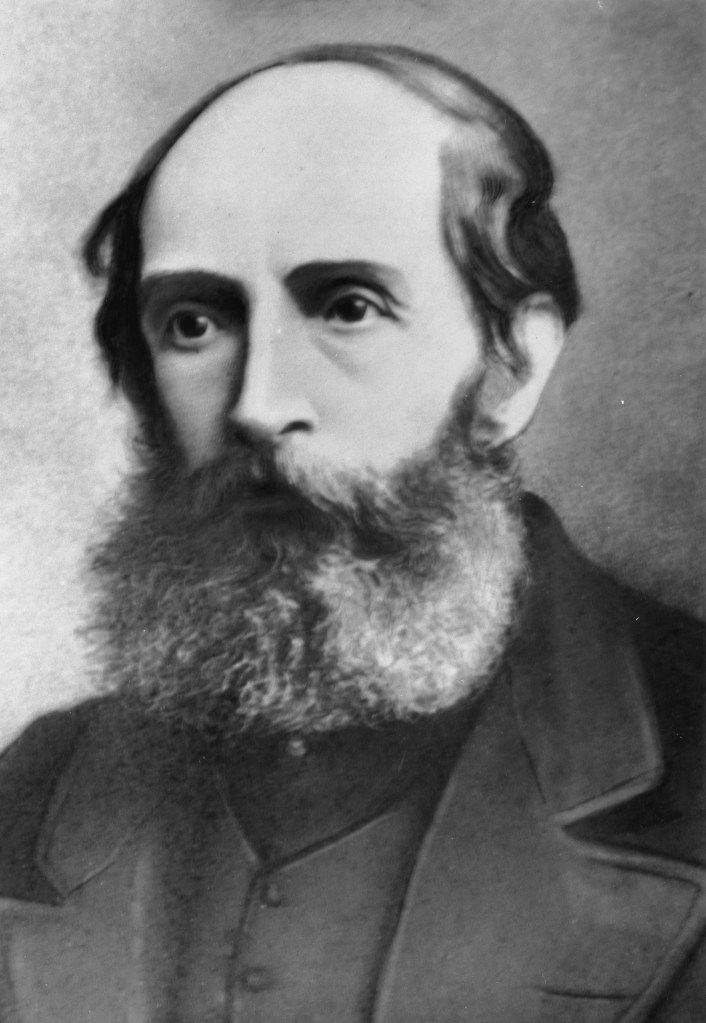

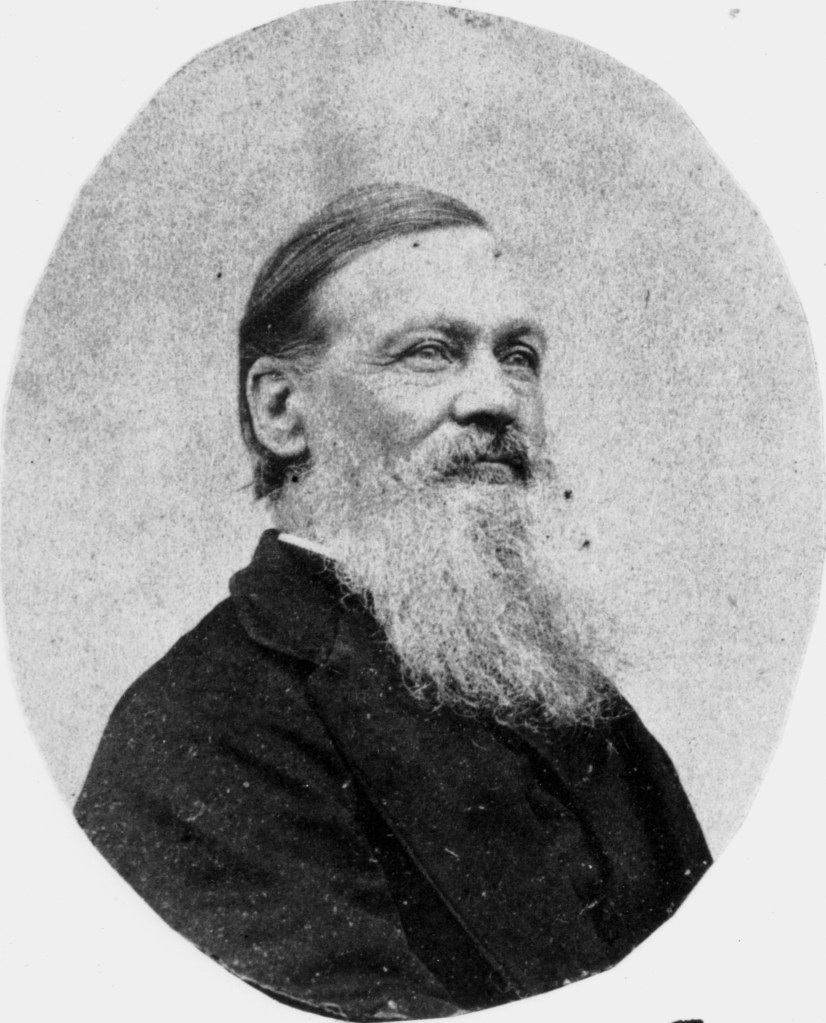

Arthur Wilcox Manning

Arthur Wilcox Manning was born in Paris in 1819, and had journeyed back and forth between England and Australia as a child, finally settling permanently in the colonies at the age of 20. He had been a civil servant for many years, and in the 1860s was the Under Colonial Secretary in the colony of Queensland. Manning had known Frank Bowerman for years – at least since the Separation from New South Wales in 1859. Initially, the men were friends – Manning’s letters were usually addressed Bowerman as “My Dear Bowerman,” and ended “Yours ever truly.” Manning also supported Bowerman’s claims for advancement in the early 1860s – at least until Bowerman began to make a nuisance of himself.

The problems started with a high-level official visit to the Downs, and the loan of Bowerman’s mare to Mrs Manning for use during the visit. The mare developed sores, and Bowerman blamed the Mannings for not securing the blanket under her saddle. Bowerman said some hasty things to the vet he took the mare to, these hasty things were repeated to the Mannings, and offence was taken. Apologies and clarifications were made and the friendship resumed. Bowerman, perhaps not the most reasonable individual, decided in hindsight that Manning had taken against him from that incident.

As the 1860s progressed, the amount of correspondence from Frank Bowerman to Arthur Manning (and the Colonial Secretary’s office) became overwhelming. Bowerman wrote seeking promotion, he wrote explaining his peculiar handling of electoral rolls and land sales, he wrote about the slight in Parliament, he wrote about his career in New South Wales, and he wrote about his travelling expenses. Manning’s replies were considerate, even kindly, at the beginning of the decade, becoming formal and distant as Bowerman’s problems magnified.

“Nanango” and the Final Straw.

The Board of Inquiry had recommended that Bowerman be disciplined, but not dismissed from the civil service. The Government decided to follow their recommendation and appoint Bowerman as Clerk of Petty Sessions at Nanango, and to remove him from the Bench and the commission of the peace. Bowerman viewed this decision not with relief, but as a personal insult. He began to deluge Manning with requests for advances of his salary, in order to travel to the place that he could only ever bear to refer to in inverted commas – “Nanango.”

Arthur Manning advised Frank Bowerman to find sureties for his salary advance. Then he found out why Bowerman was so very anxious for that advance. The Police salary cheques for Leyburn had not been paid to them for the month of September. Frank Bowerman had cashed the cheque and taken the money to accommodate himself in Brisbane during the inquiry. Now, he needed funds to pay those police officers whose salary he’d appropriated. That was the final straw. Arthur Manning instructed the Treasury pay clerk not to hand over Bowerman’s salary advance until he’d seen Manning. That was the morning of November 24, 1868. Bowerman, knowing that he’d been discovered before he could right his wrong, went to see the Under Colonial Secretary.

The Colonial Secretary’s Office, 24 November 1868

Just after 9 am, Frank Bowerman sought out Arthur Wilcox Manning in the Colonial Secretary’s Office (the low-set building in the above photograph). He wanted to know why the Treasury pay clerk had directed him to see Manning. A tense interview followed, and Manning told Bowerman that this new breach of the rules would most likely result in dismissal. Bowerman begged Manning not to tell the Colonial Secretary. Manning said that he could not cover this up, even “for his own brother.”

Bowerman left the office in a panic, and in the course of the next couple of hours, purchased a tomahawk, and drank for hours with a group of men as “reckless and desperate” as himself. In the middle of the day, Bowerman returned to see Manning, who had indeed told the Colonial Secretary about the misappropriation.

Bowerman produced the tomahawk from his jacket and attacked Manning’s head and shoulders. Arthur Manning received five injuries. Three incised wounds on the head, and two other deep wounds on the back and side of his neck. He lost a lot of blood, and Dr O’Doherty, who was one of several medics summoned, found that Manning’s life was in danger from arterial bleeding. Manning’s skull had been fractured, one blow had pushed the bone upwards, leaving a gash half an inch wide. If he had not been attended to quickly, he would have died on that day.

Frank Bowerman was taken into custody by Arthur Palmer, the Colonial Secretary, and lodged in the Brisbane Gaol after being charged with attempted murder.

Trial and Imprisonment

Frank Bowerman was denied bail, and waited four months to take his trial at the Brisbane Supreme Court. In later years, he claimed that he was denied the opportunity to seek legal representation, and to call witnesses in his defence. If he was suffering from these deprivations, he didn’t show it in court.

Dressed with great care and evident regard to the finish of his toilette, and looking as unlike a man oppressed with anxiety or suffering from confinement as it was possible to look, he cross-examined the witnesses with the utmost coolness, a good deal of acuteness, and in several instances when he could not get them to shape their answers to his liking, assumed a decidedly insolent, bullying tone.

The Courier.

Bowerman’s defence, or justification, was two-fold. He spent a great deal of time explaining to the jury how badly he had been dealt with by the civil service, particularly in the person of Arthur Manning. His second argument was that he was a strong, athletic sort of man, who, had he wanted to, would have killed Arthur Manning. The fact that he didn’t kill Mr Manning was simply evidence of his desire not to kill Mr Manning.

Taking it all in all, the conclusions as to Bowerman’s character, deducible from the proceedings, are, that conceit and arrogance are its main features; that, possessed of a certain degree of smartness very common in the colonies, he was quite devoid of grasp of mind or any considerable degree of intellectual capacity.

The Courier.

Mr Bowerman was hugely surprised to be found guilty by a jury of his peers, and flabbergasted to be sentenced to a life of penal servitude. So much so that the judge was forced to remind him that he could well have paid the price of his deeds on the scaffold.

Thus the former Police Magistrate at Leyburn found himself at the St Helena Penal Establishment. He spent most of those years petitioning for pardons, mercy or remission. Most notably, in 1875, he produced a 197-page handwritten statement to the then-Colonial Secretary, Arthur Macalister, explaining the circumstances that led to his commission of the crime against Arthur Manning. It’s an extraordinary mixture of genuine contrition, delusion, entitlement and self-justification. It devotes two pages to Bowerman’s admiration for Sir Charles Fitzroy, quotes every letter sent to and from persons of importance over twenty years, and veers off into deploring the early release of a couple of common bushrangers (who, to be fair to them, had never actually attacked anyone with a tomahawk). The Colonial Secretary refused to grant clemency on that occasion.

Nearly ten years after the attack on Manning, and after much petitioning from his family, and the inhabitants of his old Clerk of the Bench haunts, Frank Sydney Bowerman was released. The Executive Council made the order on 01 March 1878. That was also the day that an ailing Cordelia Bowerman, Frank’s long-suffering and unwaveringly loyal wife, passed away on hearing the news.

The Aftermath – Shifting Public Opinion.

“I grieve for him (Frank Bowerman) sincerely and have I trust long since forgiven him the unmerited injury he has done me, but at the same time I cannot but feel, severe as the sentence is, it is fully warranted by the outraged law. I promised Mrs Bowerman (senior) to support any movement made at the proper time on his behalf, and I can do no more than reiterate that promise.”

Arthur Manning to Cordelia Bowerman, 7 May 1869.

In 1869, shortly after the sentencing of Frank Bowerman, Arthur Wilcox Manning was granted a pension for life by a shocked Queensland Legislature. He had been recovering, slowly, from his injuries, and at the time, it was not thought that he would be fit to return to work. The Manning Retirement Act of 1869 was passed, guaranteeing him a pension of £600 per year for life, and his widow a pension of £300 per year should he predecease her. (It was thoughtfully repealed in 1995.)

Frank Sydney Bowerman departed for New South Wales, where his family had been living since November 1868. He made a brief trip to Dalby to give a public lecture on the wrongs done him by the law, which was politely, if not entirely enthusiastically, greeted by the citizens of the town.

Arthur Manning lived on, at first to everyone’s relief, and then gradually, annoyance. The Manning Pension, all £600 per year of it, began to rankle politicians, electors and newspaper writers. Manning gradually returned to do some work, which he did without accepting payment. A move by Archibald Meston to have the Manning Pension repealed was withdrawn when it was discovered that he still suffered the physical and emotional after-effects of the 1868 attack.

As the revenue of the colony of Queensland continued to flow into the Manning Pension, newspaper editorials and letters began to paint Frank Bowerman as the blighted hero brought low by an unforgiving autocrat, who now lived quite a easy life on their money. Manning and family moved to Sydney, which only annoyed Queenslanders more – why should our revenue be enjoyed by an apparently healthy old man in another colony?

The End.

Frank Sydney Bowerman lived in New South Wales with (or, more realistically, on) his family. His son and namesake commenced a career in the civil service of New South Wales.

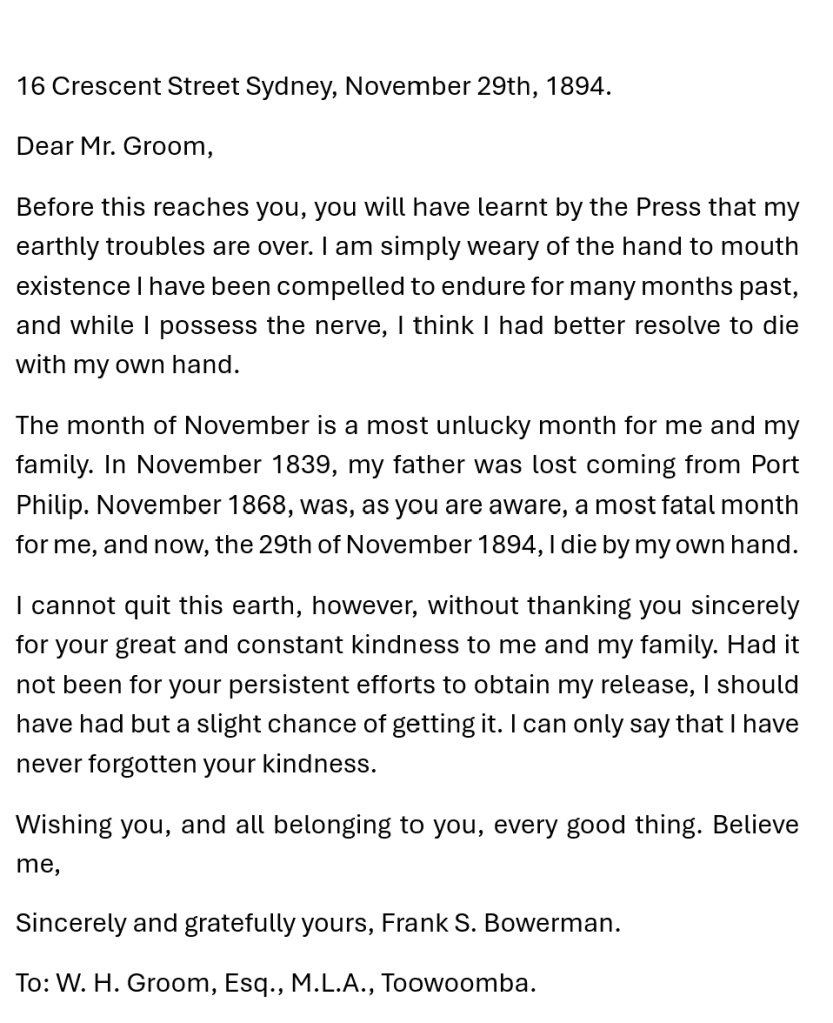

On the morning of 29 November 1894, a respectable-looking elderly man was found lying in the Sydney Botanical Gardens, near death from an apparent poisoning. He was taken to the Sydney Hospital, where he briefly rallied, before dying the following day. Notes in his pockets addressed to his sister and to the Coroner, identified him as Frank Sydney Bowerman. Before taking the poison, he had written to William Groom, one of his old supporters.

Arthur Wilcox Manning died on Christmas Day, 1899 at Sydney. By that time, most people had forgotten the terrible events of thirty years before, and his passing was marked by a brief paragraph in the Mackay Mercury.

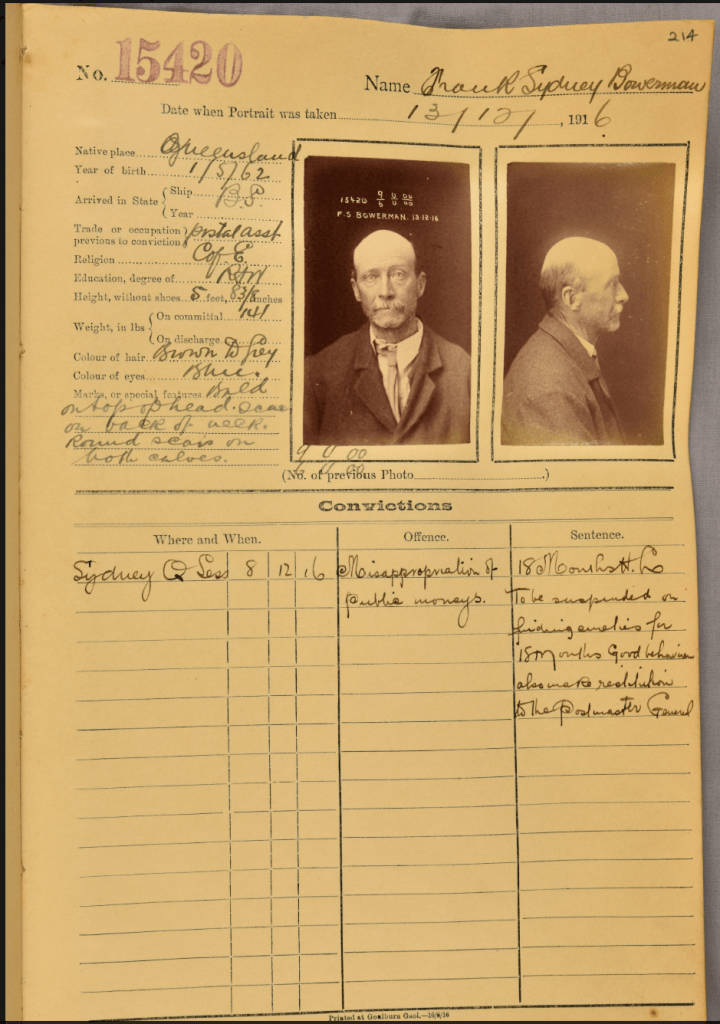

Postscript

Here is the conviction record for one Frank Sydney Bowerman, of the Post Office, who was convicted of misappropriation of public money. In 1916. Perhaps a careless attitude to public funds was a genetic inheritance. Unlike his impulsive and ambitious father, he admitted to the misappropriation and was given a good behaviour bond.

New South Wales Colonial Secretary’s Papers – State Records Office of New South Wales. (1848-1860)

Queensland Colonial Secretary’s Papers – State Library of Queensland. (1850-1878) Contains some of the NSW correspondence as well.

Newspaper Sources:

Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842 – 1954), Tuesday 5 June 1849, page 3.

Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer (NSW: 1845 – 1860), Saturday 9 June 1849, page 1.

Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld.: 1858 – 1880), Thursday 28 November 1861, page 3

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Thursday 9 January 1868, page 3

The Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864-1933) Monday 23 March 1868, Page 4.

Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser (Qld.: 1866-1879) Saturday 18 April 1868, Page 2.

The Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld.: 1858-1880) Thursday 14 May 1868, Page 2.

Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld.: 1858 – 1880), Tuesday 2 June 1868, page 3

The Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld.: 1858-1880) Tuesday 4 August 1868, Page 3.

Warwick Argus and Tenterfield Chronicle (Qld.: 1866-1879) Wednesday 23 September 1868, Page 4. Warwick Argus and Tenterfield Chronicle (Qld.: 1866 – 1879), Wednesday 7 October 1868, page 2.

Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld.: 1867-1919) Saturday 10 October 1868, page 2.

Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld.: 1867 – 1919), Saturday 10 October 1868, page 2.

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Saturday 17 October 1868, page 3.

Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld.: 1867 – 1919), Saturday 7 November 1868, page 2

The Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864-1933) Monday 9 November 1868, page 2.

The Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864-1933) Monday 16 November 1868, page 2.

Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld. : 1867 – 1919), Saturday 21 November 1868, page 2

Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld.: 1858 – 1880), Wednesday 25 November 1868, p 2

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 25 November 1868, page 2

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Thursday 26 November 1868, page 3

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Saturday 12 December 1868, page 4

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 16 December 1868, page 3

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Wednesday 23 December 1868, page 2

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Saturday 2 January 1869, page 4

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Thursday 21 January 1869, page 2

Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld.: 1867 – 1919), Saturday 13 February 1869, page 3

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Tuesday 26 January 1869, page 5.

The Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864-1933) Wednesday 3 March 1869, Page 2. The Courier.

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Saturday 13 March 1869, page 3

Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1908), Saturday 3 April 1869, page 3.

Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld.: 1866 – 1939), Saturday 10 July 1869, page 4

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Thursday 23 September 1869, page 3

Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser (Qld.: 1866 – 1879), Saturday 28 May 1870, page 2

Queenslander (Brisbane, Qld.: 1866 – 1939), Saturday 13 August 1870, page 8

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Thursday 15 December 1870, page 2

Toowoomba Chronicle and Queensland Advertiser (Qld.: 1861 – 1875), Saturday 2 May 1874, page 3

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Friday 16 February 1877, page 2

The Warwick Argus and Tenterfield Chronicle (Qld.: 1866-1879), Thursday 22 February 1877, page 2.

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Friday 2 March 1877, page 2

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Saturday 2 March 1878, page 4

Toowoomba Chronicle and Darling Downs General Advertiser (Qld.: 1875 – 1879), Tuesday 5 March 1878, page 3

The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872-1947), Thursday 7 March 1878, page 2. Shipping Intelligence.

Western Star and Roma Advertiser (Qld.: 1875 – 1948), Saturday 23 March 1878, page 3

The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872-1947), Monday 6 May 1878, page 2. Shipping Intelligence.

The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872-1947), Tuesday 18 June 1878, page 2.

Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864 – 1933), Monday 5 August 1878, page 2

Dalby Herald and Western Advertiser (Qld.: 1866-1879), Saturday 10 August 1878, page 2.

The Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser (Toowoomba, Qld.: 1858-1880), Saturday 17 August 1878, page 4.

The Brisbane Courier (Qld.: 1864-1933), Monday 2 September 1878, page 2. Shipping.

Toowoomba Chronicle and Darling Downs General Advertiser (Qld.: 1875 – 1879), Tuesday 25 March 1879, page 2

Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.: 1878 – 1954), Wednesday 21 May 1879, page 2

Morning Bulletin (Rockhampton, Qld.: 1878 – 1954), Tuesday 3 June 1879, page 2

Warwick Argus (Qld.: 1879 – 1901), Saturday 1 November 1890, page 3

Australian Star (Sydney, NSW: 1887 – 1909), Thursday 29 November 1894, page 5

Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld.: 1872 – 1947), Saturday 1 December 1894, page 5

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld.: 1860 – 1947), Monday 3 December 1894, page 2

Toowoomba Chronicle and Darling Downs General Advertiser (Qld.:1881 – 1902), Tuesday 4 December 1894, page 3

Daily Telegraph (Sydney, NSW: 1883 – 1930), Friday 7 December 1894, page 3

Mackay Mercury (Qld.: 1887 – 1905), Tuesday 2 January 1900, page 2

Illustration sources:

Sydney:

Sydney between1825 and 1830. Copy after an engraving “Vue de la partie meridionale de la ville de Sydney” by Victor Pillement. Plate 38 in “Voyage de decouvertes aux terres australes,” Atlas / Francois Peron. National Library of Australia.

St John’s Parramatta “View of St. John’s Parramatta,” pencil, by M.A. McHarg, 1842. National Library of Australia.

General Post Office “New Post Office, George Street, Sydney,” 1846, hand-coloured lithograph by F.G. Lewis and Edward Winstanley, Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales

Majors Creek pictures

“My tent at Majors Creek, Braidwood,” 1852, pencil, by William Essington King, State Library of New South Wales.

“Majors Creek Diggins from my tents,” 1852, pencil, by William Essington King, State Library of New South Wales.

Sofala pictures

“Commissioners barracks at Sofala, diggers waiting for licences,” watercolour, 1852 by George Lacy, National Library of Australia.

“Mounted escort from Avisford to Sofala, gold carried in saddle bags, Sub Gold Commissioner in charge,” watercolour, 1852 by George Lacy, National Library of Australia.

Kelso:

Kelso parsonage, part of Series 03 Part 2: Churches – Country (N.S.W.), C-Ma volume 2, Architectural and Technical Drawings, State Library of New South Wales.

Dalby images:

Wooden Hotel Building, Dalby. Black and white photograph, State Library of Queensland.

View of the town of Dalby. Black and white photograph. State Library of Queensland.

Bamford & Watt Auctioneers, Dalby. Black and white photograph. State Library of Queensland.

J Clark’s Universal Store, Dalby. Black and white photograph. State Library of Queensland.

Leyburn images:

Charles Bell’s Commercial Store, Leyburn. Black and white photograph. State Library of Queensland.

Leyburn Courthouse. Black and white photograph. State Library of Queensland.

James Mahony’s Store and residence, McIntyre Street, Leyburn. Black and white photograph. State Library of Queensland.

Brisbane:

Frederick Orme Darvall. State Library of Queensland.

Sir Augustus Charles Gregory. State Library of Queensland.

William Thornton. State Library of Queensland.

William Street view with detail of CS office:

William street in Brisbane in 1865. Black and white photograph. State Library of Queensland.

Detail of William Street in Brisbane in 1865, showing Colonial Secretary’s Office on the left. Black and white photograph. State Library of Queensland.

Arthur Wilcox Manning

Arthur Wilcox Manning. Black and white photograph. State Library of Queensland.

Old Convict Barracks now used as Supreme Court

Brisbane Gaol and St Helena

St Helena at Low Tide. State Library of Queensland.

Sydney Botanical Gardens

Botanic Gardens, Sydney, N.S.W. 1890s [rustic bridge over Botanic Gardens Creek]. Author / Creator: Coxhead, F. A. (Frank Arnold), 1851-1919. Black and white photograph. State Library of New South Wales.

Gaol Description and Entrance Book photograph: Frank Sydney Bowerman, 1916. State Records Office of New South Wales.