A brief guide to the patent medicines advertised so relentlessly throughout Old Queensland’s newspapers.

Holloway’s Pills.

Undoubtedly the greatest man of the day as an advertiser is Holloway, who expends the enormous sum of twenty thousand pounds annually in advertisements alone; his name is not only to be seen in nearly every paper and periodical published in the British Isles, but as if this country was too small for this individual’s exploits, he stretches over the whole of India …publishing his medicants in native languages, so that the Indian public can take the Pills and use his Ointment, according to general directions, as a Cockney would do within the sound of Bow bells.

Pictorial Times, 1847.

Thomas Holloway (1800-1883) was an English businessman who saw potential in making patent medicines, and even more potential in advertising them. Beginning in 1837, his advertisements for his ointment and pills appeared daily in newspapers on every continent. These advertisements included florid testimonials from apparently real people, disclosing “cures” for everything from paralysis to “Determination of Blood to the Head,” as suffered by a Miss Henrietta Wright of Maitland, NSW.

Holloway’s extraordinary wealth allowed him to fund a health sanitorium and the Royal Holloway College of the University of London. After his passing, his heirs cut back on the advertising budget, and Holloway’s Pills gradually lost their market share to Beecham’s Pills.

In 1903, the British Medical Journal, conducting a review of patent medicines and “cure-alls,” analysed Holloway’s Pills. These apparently miraculous tablets contained aloes, rhubarb, saffron, sodium sulphate decahydrate and pepper. Holloway’s Ointment contained turpentine, resin, olive oil, lard, wax and spermaceti. The ointment may have had a soothing effect on itchy skin. The pills would have had a mild laxative effect.

And Beecham’s Pills, the successor to Holloway’s? They contained aloes, powdered ginger, and powdered soap. They were supposed to take care of everything from flatulence to acne to “menstrual derangements.”

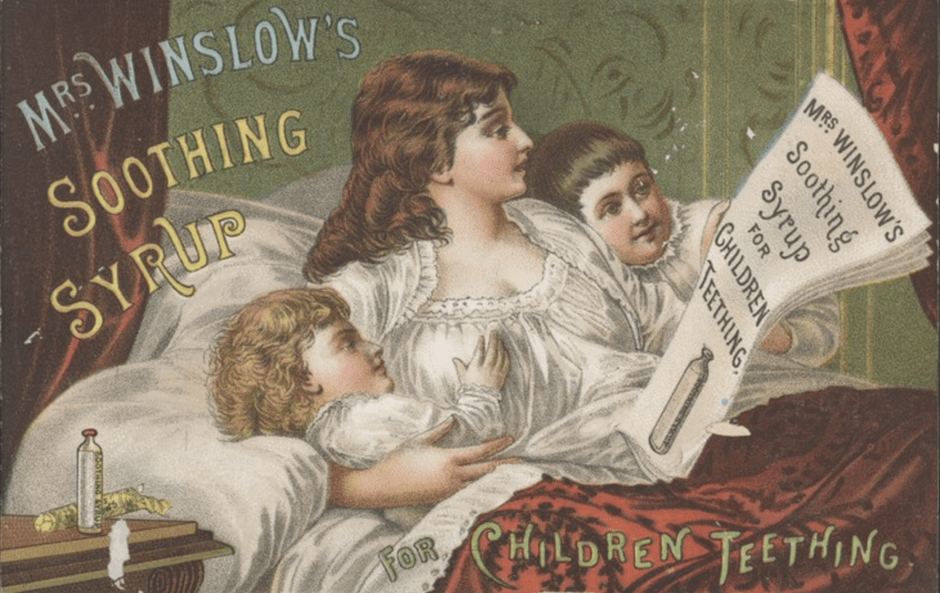

Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup.

One look at that advertisement made me think that Mrs Winslow was putting a fairly strong sedative in her syrup. All that talk about immediate relief and quiet sleep. I suspected that some little cherubs might have suffered a deeper sleep than intended, and a quick glance through contemporary newspapers confirmed that suspicion.

In New Zealand in 1877, an inquest was held into the death of an infant named Frederick Blake, who had been given the recommended dose of Mrs Winslow’s medicine. The treating doctor was well aware of the syrup, and referred to the works of Professor Taylor and Dr Hoffman, which showed that “every ounce of this syrup contains one gram of morphia.” A decade later, a little boy in Melbourne died after being administered the syrup. The Government Analyst was called to give evidence – the syrup he examined had contained a “considerable quantity of opium.”

The product, which originated in 1845 in Maine, continued to be sold until 1930. Here’s the American Medical Association in 1911, who placed Mrs Winslow’s Syrup under the heading “Baby Killers.”

Feeling fagged? Worn out? Giddy? Spotty? Eno’s will fix that!

Although it had little to no effect on depression or pimples, it did help settle Victorian stomachs in the days before food refrigeration. Eno’s tended to be advertised (particularly in regional newspapers) with large illustrated advertisements showing vibrantly healthy tots at play.

Eno’s is still available today, and is sold simply as an antacid. The product was taken over by Beecham, by 1938 a pharmaceutical giant in its own right.

For “Rickety Children” and “Derangement of the Stomach and Bowels.”

Not to mention cigarettes for asthma.

Grimault and Co and Dusart created some treatments that, asthma cigarettes aside, had their origins in indigenous and tropical medicine.

Matico or Piper Anduncum is part of the Piperaceae family, and is found in Central and South America. The leaves have been used as an antiseptic in the Amazon. In traditional Peruvian medicine, it was used for treating hemorrhages and ulcers, and in Europe was used for urinary tract infections.

Guarana, Paullinia Cupana, is another South American plant whose seeds produce high levels of caffeine, and is used in energy beverages today. In the 19th century, guarana was used to treat headaches. If the headache wasn’t helped by the guarana, at least the sufferer would feel remarkably energetic for a time.

Syrup of lactophosphate of lime was used as by dentists, particularly for use on the gums after an extraction. Here’s the American Dental Register of 1874 with the instructions for making it. No mention of rickets or nursing mothers.

“For diseases incident to Tropical and Colonial life.”

Lamplough’s Pyretic Saline was advertised as the “cure and preventive of most diseases incident to Tropical and Colonial life.” It was recommended for “Station proprietors, Flockmasters, and all residing up-country.” The product was said to cure everything from “jungle fever” to sea sickness to pimples.

As far as the modern reader can discern, this was an effervescent saline drink that probably helped treat the effects of dehydration and indigestion, colonial, tropical or otherwise. Lamplough’s advertised in a very dignified manner, avoiding the cherubic children of Eno’s and Mrs Winslow.

Persons of a full habit.

Other frequently advertised cure-alls included Frampton’s Pill of Health. This pill claimed to be good for “Females” to “remove all obstructions” (eh?) and “the distressing headaches so very prevalent with the sex.”

“Persons of a full habit” could look forward to relief from headaches, drowsiness, and rushes of blood to the head. An earnest search of sources devoted to arcane language yielded a definition of persons of a full habit – heavily overweight people with flushed complexions.

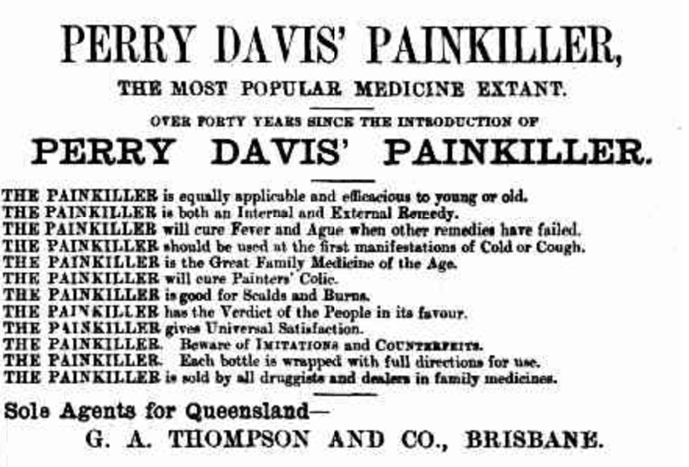

Painter’s Colic.

I don’t know what Perry Davis put in his painkiller, but it could help with Painter’s Colic, it claimed. Sadly, it might have relieved the symptoms of Painter’s Colic, but the cause was a potential death sentence. The condition was described as extremely severe colic pain and constipation, and was so named because people who suffered from it typically used lead-based paint in their work.

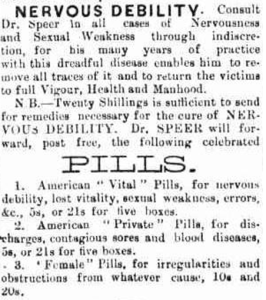

Nostrums for unmentionable things.

Lastly, there was Dr Speer. Dr Speer claimed to have spent two decades studying “CHRONIC and SPECIAL diseases of MEN and WOMEN.” What these might be is revealed by the next line – “no mercury used.” Charges moderate. Becoming even franker, unusually so for 1892, Dr Speer offered:

The doctor was conveniently located in Sydney, and offered diagnosis and treatment by mail order, just like the various “Mother” this/that who offered young women a way out of unwanted pregnancy, but robbed them of their shillings, if not their lives.

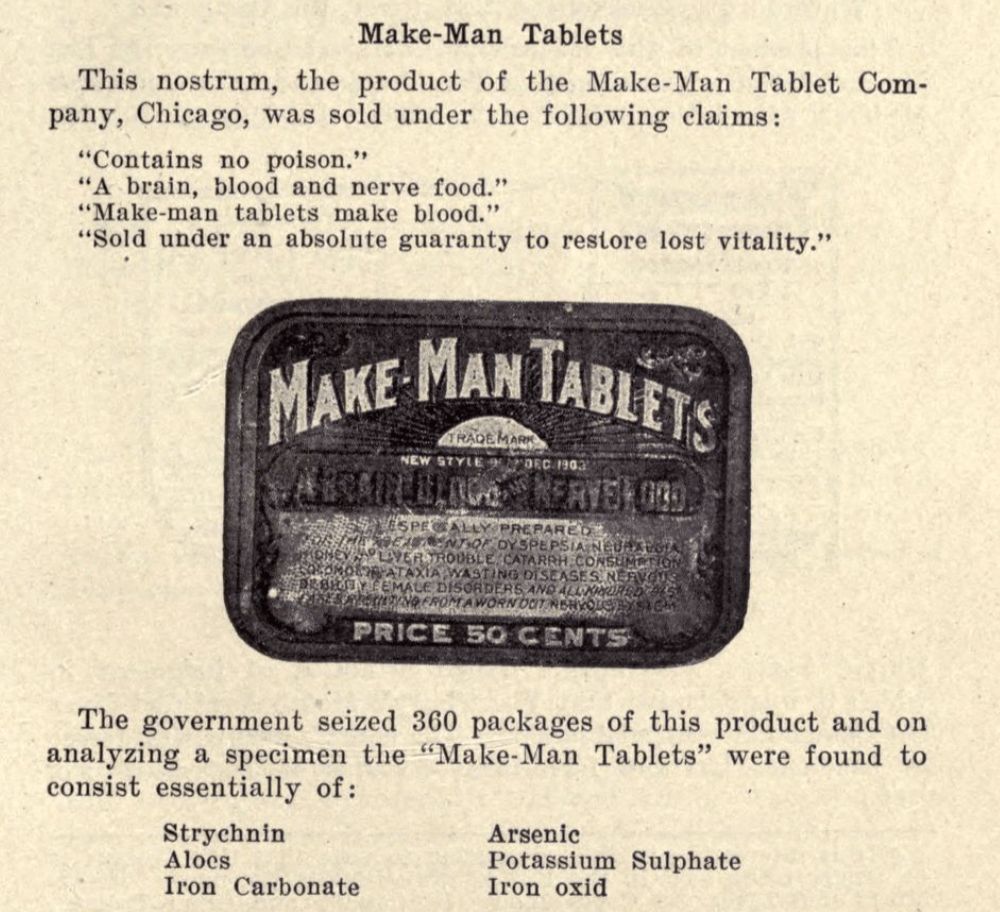

The Rogue’s Gallery of Patent Medicines.