Timothy Duffy was an Irish convict, who had been transported for highway robbery in 1822, and who became a familiar and well-liked figure in early Brisbane as the Bay Fisherman. His progress towards reform and respectability was slow, and some would say, incomplete. He liked a drink, hated a bailiff, and could curse with legendary ferocity. Even in his middle years his nickname was “Fireball.”

Highway Robbery in Dublin.

DUBLIN POLICE. On Thursday last, while in the act of apprehending a boy of the name of Kavanagh for a robbery, David Courtney, watch constable, was violently struck and abused by a man who calls himself Timothy Duffey. There being every reason to suppose he was an accomplice of Kavanagh, he has been committed to Newgate.

Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser, Dublin, Ireland. 1821.

Above: Views of Georgian Dublin.

Timothy Duffy was born in Dublin in 1803. While still a lad (teenagers had not yet been invented), he nicked linen goods and scuffled with the constables, before earning himself a one-way, all-expenses-paid trip to the New World in 1822 for highway robbery. He had escaped the noose, but was bound for the colonies.

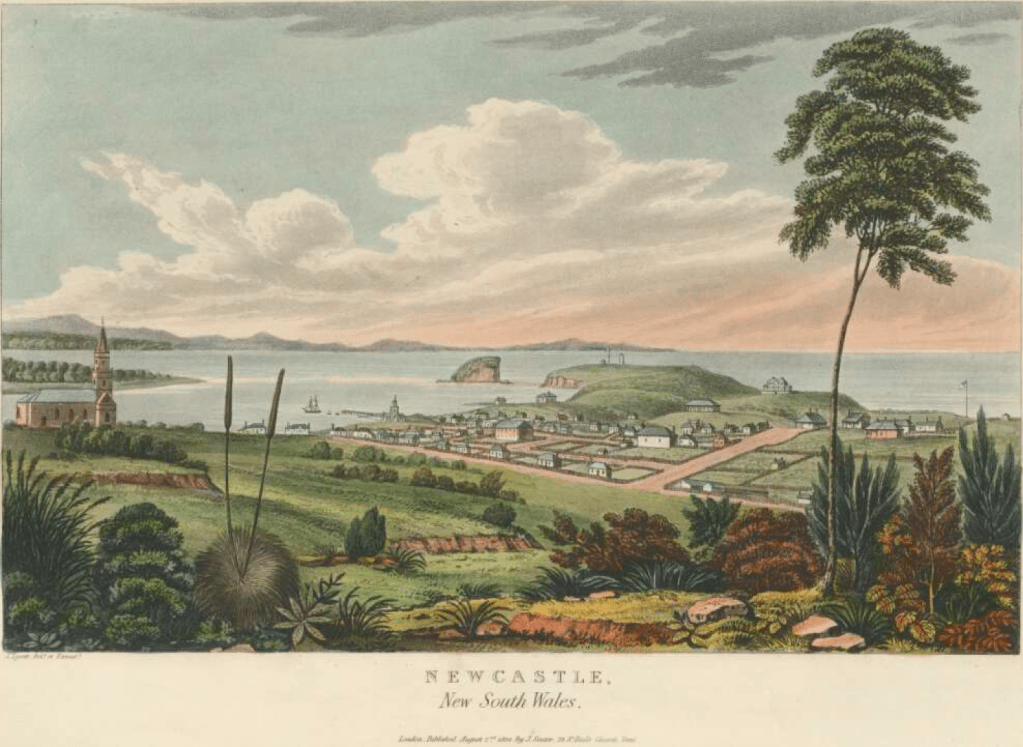

Duffy arrived in New South Wales on the Countess Harcourt in December 1822. His indent shows that he was 19 years old, 5 feet 7 ½ inches high, of stout build, with brown hair and eyes. He was a garden labourer by trade, and was sent to work as an assigned servant in the settlement of Newcastle.

Newcastle.

Timothy’s stay in Newcastle began reasonably well. He was assigned to Lieutenant Close, and was granted permission to pass with stock from Windsor. By mid-1825, he seems to have come to appreciate that being an indentured labourer for a load of pompous redcoats would be his lot for the next 14 years, and he began to rebel.

Timothy Duffy in the service of government, charged with riotous and disorderly conduct in the street. The chief constable states – I saw Duffy yesterday afternoon stripping himself to fight. – There had been some disturbance in the street and Duffy had challenged a soldier who was present. The prisoner made no defence. Sentenced to hard labour in the gaol gang for 28 days

Newcastle Bench of Magistrates, 22 June 1825.

This clearly had little effect, and soon enough he absented himself from Divine Service, earning himself 48 hours on bread and water as penance.

In 1826, Duffy was out of Barracks and intoxicated at “unreasonable hours,” which meant 8 o’clock in the evening. He threw himself on the mercy of the court, and received a reduced sentence of 25 lashes.

A bit of good fortune came Timothy’s way in November 1826, when he avoided prosecution for gambling with a group of prisoners in a hut in St Patrick’s Street. Their former overseer, who was very drunk, spotted them through a window and told a constable. When the constable got to the place in question, the men were sitting around looking all innocent. No gambling tools in sight. Nothing to see here, Sir.

A month later, Wilkins (the former overseer who’d snitched on the gambling party), came home to find he’d been robbed of his trowsers and undergarments. An indigenous youth told him that the culprit was Timothy Duffy. On being questioned, Duffy said he wasn’t involved, but he knew who was. He pointed the finger at two other prisoners, and gave evidence before the Magistrates. The two men were acquitted because the Bench felt that the “notoriously bad character” of Duffy led them to doubt the veracity of his evidence.

The following month, Duffy decided to well and truly live up to his reputation as a notoriously bad character.

In January 1827, an infirm elderly man named Charles Griffiths was walking home along the road from Newcastle with some small groceries when he was hit hard on the head from behind. He was robbed of his tea, sugar, spectacles, shoes and coat. When he woke up, he noticed a dirty handkerchief, not his own, nearby.

Timothy Duffy’s hut-mates noticed that he had acquired some tea and sugar, as well as shoes and a jacket. He’d also lost his handkerchief. No-one had any difficulty connecting the dots, and Duffy’s behaviour about his new property was highly suspicious. In June 1827, at the Criminal Court in Sydney, Duffy was found guilty of highway robbery and putting Charles Griffiths in bodily fear. He was sentenced to death.

A week later, an Executive Warrant arrived at Sydney Gaol, and Timothy Duffy was one of the prisoners given a reprieve. But he would have to spend life in chains at Norfolk Island.

Norfolk Island.

Norfolk Island was far enough from Sydney to make it attractive to the British Government as a place of penal settlement. It was uninhabited, well forested, and in some danger of being claimed by other colonising European countries. The resulting penal colony limped along in a state of isolation and want from 1788 to 1813, and was reopened in 1824 to house the worst kind of convicts – recidivists. Moreton Bay was set up with much the same intention the same year, but it had the comparative advantage of being on the Australian mainland. As much as convicts hated Moreton Bay, the prospect of Norfolk Island was horrifying – equivalent to a slow death sentence.

Timothy Duffy was unloaded from the Phoenix Hulk in Sydney in August 1827 and sent aboard the Governor Phillip to Norfolk Island. He remained there under eight Commandants of varying degrees of outright despotism, lived through prisoner-on-prisoner murders, escapes, executions, and the deadly convict mutiny of 1834.

A brief, eventful trip to Sydney.

In October 1829, Timothy Duffy had what might be described as a vacation – he was brought to Sydney with some fellow-prisoners to give evidence at the Supreme Court. The Isabella took him back to the Phoenix Hulk, hardly an ideal destination, but presumably a change was as good as a holiday. There were two major trials to be held with reference to Norfolk Island, and which matter Duffy was brought in for is unclear. The first, and most sensational trial was that of Captain Thomas Edward Wright of the 39th Regiment, for murdering an escaped prisoner named Patrick Clinch in October 1827. The second case was that of a prisoner named either Keley, Riley, or John Magennis (depending on the newspaper), for wounding a fellow prisoner named John Hughes.

Timothy Duffy was not recorded as being a witness in Wright’s trial, which was discontinued after a fellow soldier gave exculpatory evidence. The mystery prisoner case did not proceed because not all of the witnesses had been taken to Sydney.

The journey back to the Island was not without incident. As the Isabella was being fitted out for the return journey, the ship’s cook, James Wilson, went to share a drink with some crew on the nearby Lucy Ann. As Wilson was making his way back along a plank between the two vessels, he slipped and fell into the water in the dark. His death was ruled an accident brought about by intoxication.

Then, as the prisoners were being mustered on the Isabella for the return journey, one of the soldiers in charge accidentally discharged his own pistol. The shot went through both of his thighs, and he was removed to the Hospital in a dangerous condition.

After the dramatic departure from Sydney, the convicts were safely delivered back to Norfolk Island in November 1829, and we hear nothing more about Duffy until September 1831, where a brief note on his record records him being given 50 lashes at Norfolk Island. He seems to have avoided the uprising in 1834, but there is another note on file that he spent 6 months in irons for threatening – who or what is unclear.

Back to the Mainland.

By mid-1840, a number of long-term and no doubt long-suffering prisoners at Norfolk Island began to receive commutations of their sentences. The newest Commandant of Norfolk Island, Captain Machonicie, had put in place a more forgiving regime for the prisoners, and morale had improved. The older hands among the prisoners were said to be a little resentful of the kinder treatment given to the new recruits, but the commutations calmed their feelings, and helped with the overcrowded state of the settlement.

Timothy Duffy had been there for the better part of 13 years, and was one of the 90 prisoners put on board the Governor Phillip for Sydney on 19 August 1840. And, in a strange echo of the tragic events on the Isabella in 1829, a sailor from the Governor Phillip named Charles Cuthbert threw himself overboard at Sydney. Cuthbert was said to be “in a fit of derangement,” and drowned before the boats could be lowered to rescue him.

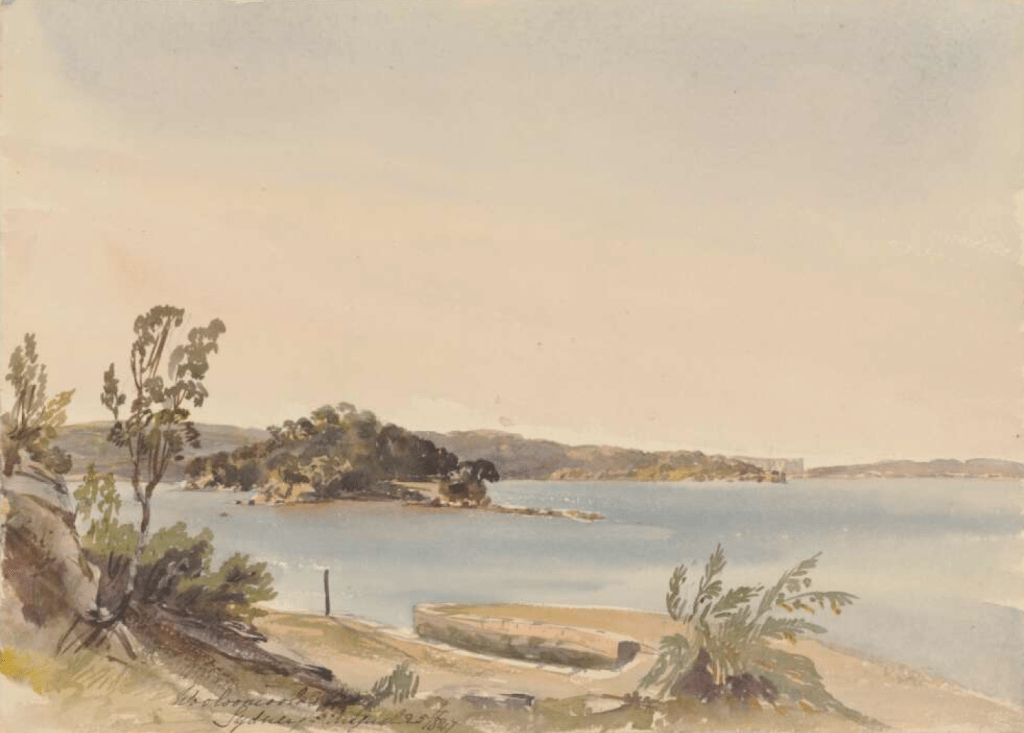

Timothy Duffy was lodged at Hyde Park Barracks, then assigned to the Ironed Gang at Woolloomooloo on 14 September 1840, with his fellow Norfolk Island veterans.

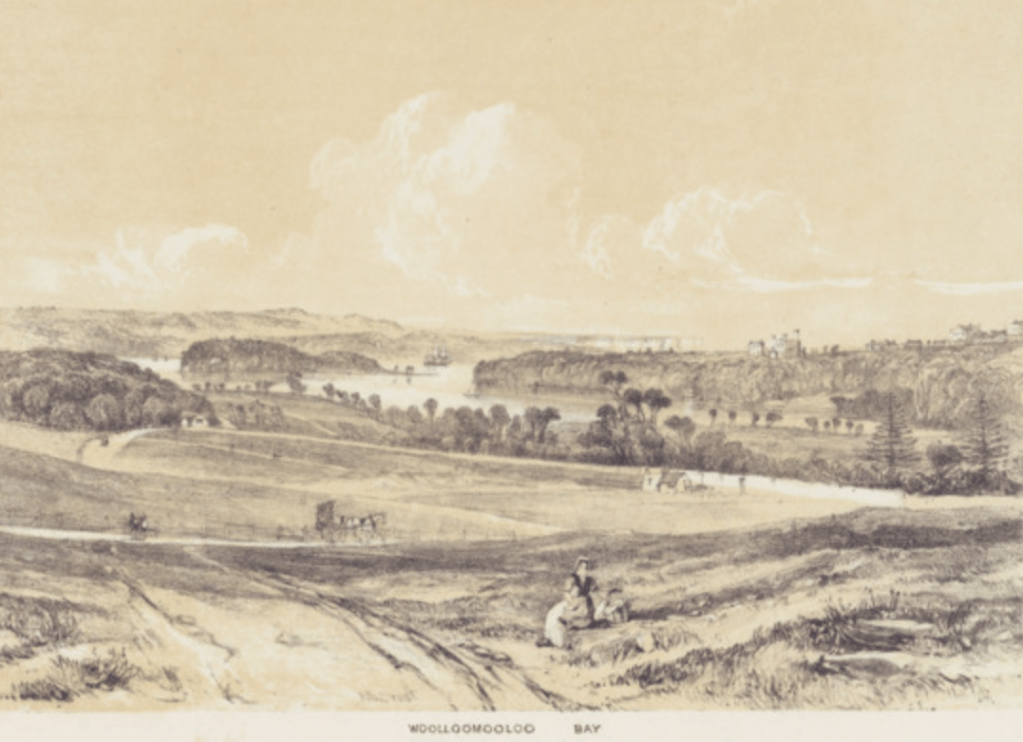

Two views of Woolloomooloo in the 1840s.

Woolloomooloo, a beautiful harbourside area of Sydney, was a picturesque place to be worked in irons, one supposes. Duffy, now aged 37, seems to have kept his head down and worked through it with a Ticket of Leave in mind.

Keeping himself (reasonably) well-behaved was a good strategy. Duffy was sent to work at Parramatta, and finally received his Ticket of Leave on 25 January 1844. Timothy Duffy petitioned the Bench at Parramatta for a variation of his Ticket of Leave to permit him to live and work at Moreton Bay. This was granted on 01 July 1844.

Parramatta in the 1840s.

Moreton Bay and Kangaroo Point.

Timothy Duffy settled in the newly-opened Brisbane Town in 1844, choosing the riverside area of Kangaroo Point as his home. He would live in and work from that suburb for the rest of his life.

Although his original calling had been as a garden labourer, Duffy had become a skilled mariner and fisherman. He set up a crew of mostly indigenous fishermen, and worked the river and Moreton Bay, returning to town to sell his fresh fish.

Duffy had a solid working relationship with his indigenous crew, much like another Bay fisherman Eugene Doucette, who had come from Mauritius as a convict in 1840. Doucette lived among the Turrbal people and learned their language, sometimes attending the Brisbane courts as an interpreter. It’s fairly unlikely that spiky, Irish Timothy Duffy took the trouble to become fluent in Turrbal, but he may have known a little phraseology and some fishing customs. Although Duffy did not live in camps with the Turrbal, Kangaroo Point at that time was still a place of indigenous habitation in the 1840s, and indigenous families lived close by.

Shooting at Kangaroo Point.

In late April 1848, a strange incident took place at Kangaroo Point. Timothy Duffy was drunk, and apparently annoyed at something the indigenous people there were doing or had done. An indigenous man named Mickey alerted Constable Beardmore to his belief that Timothy Duffy was about to “shoot at the blacks.”

Beardmore noticed Duffy running towards Mr Mowbray’s place, then saw Duffy come out of his house with a what looked like a gun in his hand, and fire in the direction of the indigenous people.

Beardmore thought that Duffy was trying to frighten, rather than hurt, when he fired. Another indigenous man, Malroben, spoke to the Magistrates through Eugene Doucette, stating that Duffy had been drunk, had fired a musket, and that small shot had hit his mother in the chest. Malroben said that Duffy was normally friendly with the local indigenous people, being particularly fond of Malroben’s mother. The Court sent some constables to bring the old lady to Court, and adjourned the case.

A week later, Malroben’s mother was brought to the court, and gave evidence that Timothy Duffy had not shot at her. She was able to show that she had no injuries. Her view was that Duffy had fired a gun, but not at her. The noise had frightened her, and she and her son ran to their camp.

The weapon found on Duffy had no shot in it, but had some powder remaining. The gun might have made a “slight report” when fired. There had been no shot or powder found at Duffy’s house.

Clearly there had been a weapon, however defective, and Timothy Duffy had fired it in the presence of indigenous people, and frightened them. He was committed to take his trial in Sydney, which was the only option in the days before Moreton Bay had a circuit court. Duffy’s ticket of leave was cancelled, and he was sent to Darlinghurst Gaol to await trial.

In early June 1848, Duffy faced the Chief Justice, charged with shooting with intent to murder, and shooting to cause grievous bodily harm. Constable Beardmore gave his evidence, but it appeared that no-one thought it would be worthwhile bringing the indigenous people to Sydney to give evidence.

Constable Beardmore gave evidence that Duffy had fired the gun from the shoulder, about 200 to 250 yards from the indigenous people. Under those circumstances, it was decided that Duffy could not have hit anyone with a shot, and the jury returned a not guilty verdict. Duffy returned to Brisbane Town, and his ticket of leave was restored. He continued to work harmoniously with indigenous fishermen.

In January 1850, Timothy Duffy successfully applied for permission to marry Catherine Fahy at Brisbane. The groom’s age was recorded as 46, the bride’s was 21. The couple settled down at Kangaroo Point, and began a family. Their children were Edward (born 1850), Thomas (1852), James (1856), and Catherine (1859).

A Thief in the Night.

Timothy Duffy fished the Brisbane River and Moreton Bay, sometimes camping on the bay islands for a few days with his crew. During his longer excursions, Catherine Duffy would stay at a friend’s house at night, for safety.

In July 1850, Catherine was expecting the couple’s first child, and Timothy was away. She stayed overnight with her friend, and returned home to find her place had been burgled overnight. A locked box containing a small amount of money had been opened, and its contents taken. The money taken was not a vast amount, but it was all the money she had until Timothy was able to bring his catch in and sell it.

District Constable Murphy did a spot of crime scene examination, noting shoeprints outside the Duffy house. The boots worn by the thief left a distinctive pattern, due to a missing nail. Adding to his shoeprint analysis was a copper’s instinct, and he searched a certain ticket of leave holder named Isaac Tomlin. On Tomlin’s person, Murphy found a pound note that had been folded in the way Catherine Duffy had described. Tomlin’s boots were missing the particular nail, and the size and tread matched the intruder’s exactly. Tomlin spent the next six months on a road gang.

Framed by an “Abominable Woman.”

Mary Ann Williams wasn’t exactly the belle of Brisbane society, such as it was, in the early 1850s. Mrs Williams paid a lot of visits to the Queen Street Gaol, having been arrested 17 times previously, for drunkenness, assault, and obscenity. She had arrived free as a child in 1825, and had married George Williams in Sydney in 1844. By 1852, George Williams had separated from his drunken, turbulent wife, advising the inhabitants and vendors of Brisbane that he would not be responsible for her debts. She had a settlement from him, and he expected her to use that.

Robert Little, the future Crown Solicitor for Queensland, received visits from Mary Ann at his home office, connected with her separation settlement. One night, when under arrest for drunkenness, Mary Ann claimed that she knew about a theft from Robert Little, and who was responsible. She gave the police a complicated story involving Timothy Duffy emerging from Little’s premises with stolen booty, conspiracies formed in drinking establishments, and hidden treasure.

Timothy Duffy was apprehended, but couldn’t give any evidence about the theft, because he’d never been further than the tradesman’s entrance of Little’s house, and that was only when he had fish to sell. His interaction with Mary Ann Williams consisted of giving in to her cadging for a drink. And he had witnesses to this. The police grew tired of searching for the stolen goods, having poked around most of old Brisbane Town. They charged Mary Ann.

When the matter came to trial, Ellen “the Cutter” Semple gave evidence about seeing a stolen handkerchief in Mary Ann’s possession in prison. Timothy Duffy gave evidence. The Chief Constable gave Duffy a good character. The jury found Mary Ann guilty, and Justice Stephens told her that she was “a hopelessly abandoned wretch,” for trying to frame someone else for her crime. She was given three years in Parramatta gaol, and left the courtroom making obscene gestures. (When she requested a remission of sentence, Justice Stephens wrote a note to the Visiting Justice that she was an “atrocious character” and an “abominable woman,” who should serve every hour of her sentence.)

For Tim Duffy, it must have been a relief to receive a good character from a Chief Constable, and to have escaped a perjured charge. He had been recommended for a conditional pardon, due to the length of time since his original and secondary convictions, and the absence of any other sentences since the mid-1820s.

A Pardon and Norfolk Island Pirates.

1853 was a notable year for Duffy. In January, the Governor-General published his Conditional Pardon (the condition being that he could not return to Ireland). He was a genuinely free man, 26 years after facing the prospect of the gallows. He had survived Norfolk Island, moved to a new part of Australia, had married, and had a growing family.

In March, Duffy found himself in the unlikely role of civilian crime-stopper. A group of nine prisoners escaped from Norfolk Island in a stolen boat, and after a lot of piratical adventures, found their way to Moreton Bay (although at first they had no idea where they were). The men landed at Stradbroke Island, where they robbed a Filipino fisherman, and took a constable and coxswain hostage. The runaways split up, six taking the fisherman’s boat, and three remained on Stradbroke overnight.

“The people left were compelled to remain on the island until Monday morning, when Timothy Duffy, one of the bay fishermen, arrived with his boat and crew of blacks, and was informed of the circumstances. One of the convicts, who had been secured, had made his escape during the night, and was wandering on the island, and Duffy, on being informed of this, armed some of the blacks with a gun, and sent them in pursuit. In a short time afterwards they brought the prisoner into the camp, where he was secured, and all the party came up to Brisbane on Tuesday, at noon, when the three prisoners were lodged in gaol. Their names are Robt. Mitchell, Denis Griffiths, and James Clegg.”

The Moreton Bay Courier.

The irony of a man who had spent 13 years at Norfolk Island bringing three escapees from that place into the Brisbane Gaol would not have been lost on Duffy.

An Old Colonist.

The next few years were spent uneventfully, although Duffy was fined in January 1856 for using obscene language at Kangaroo Point. He continued to work with his crew in the Bay.

In January 1858, Timothy Duffy had a scuffle with a bailiff sent by Edward Lord to recover £16. Patrick Fitzgibbon, the bailiff in question, claimed that Duffy came to the door with his dog, and said:

“To the divil with Mr. Lord and yourself, I’m here to poke borak (fun) at Mr. Lord and yoursilf. By J–s if you don’t leave the place I’ll disable you.”

Mr Fitzgibbon felt very threatened indeed, and fled.

Clearly, three decades spent in Australia had not dissipated Duffy’s Dublin accent. Or his temper. Mr Fitzgibbon took Mr Duffy to Court for threatening him. And lost. Timothy Duffy’s lawyer was able to point out that Fitzgibbon had not informed Duffy that he was a bailiff, and further, the warrant that authorised the visit was defective. That was enough to throw the case out.

Timothy Duffy rarely made news after the dismissal of the bailiff case. He was charged with using obscene language (twice) and being drunk and disorderly. He now had four children, and remained one of the listed Fishermen and Fishmongers of Brisbane. He diversified a little by selling “first-class Spanish fowls” in 1861. In the 1860s he was fined twice for allowing his cattle to stray.

His sons caused him some concern. At one point, he refused to be responsible for any debts incurred by Thomas, and young James became quite a tearaway. In between getting into trouble for thieving, James had an accident while using explosives on one of his fishing boats, and blew part of his hand off. James graduated from the Proserpine reformatory hulk to serious time in adult prison, before leaving for New South Wales, and a life of destitution.

The rest of the Duffy family remained together at Kangaroo Point, and when Timothy Duffy died at the age of 72 in December 1875, he was remembered fondly as “an old Colonist.” Thomas, apparently forgiven for his youthful debt-incurring, was his heir-at-law, inheriting property in South Brisbane. Catherine, Timothy’s wife, passed away in 1894, and Thomas died accidentally while working at Coomera in 1896.

Related Posts:

The Convicts from Mauritius. https://moretonbayandmore.com/2022/07/24/the-convicts-from-mauritius/

Ellen the Cutter. https://moretonbayandmore.com/2025/04/29/ellen-the-cutter/

The Convict Pirates of Norfolk Island Visit Moreton Bay. https://moretonbayandmore.com/2020/11/25/the-convict-pirates-of-norfolk-island-visit-moreton-bay/

James Duffy – Crime and Misfortune. https://moretonbayandmore.com/2020/07/05/james-duffy-crime-and-misfortune/

Sources:

1 Comment