In the late 1840s, readers of the Moreton Bay Courier, were appalled and fascinated by reports of the antics of the town’s less proper womenfolk. Some were former convicts, others were wives of labourers, all were heavy drinkers. For nearly a decade, the rowdiest woman in town was Mary Ann Williams. The Brisbane Bench cautioned her, admonished her, fined her, and locked her up. When that failed, sent her to Sydney to be imprisoned for a month or so. Her Brisbane career ended in 1852, when Chief Justice Alfred Stephens sent her to Parramatta Gaol for three years with a character assessment that set her ears ringing. She certainly didn’t go quietly.

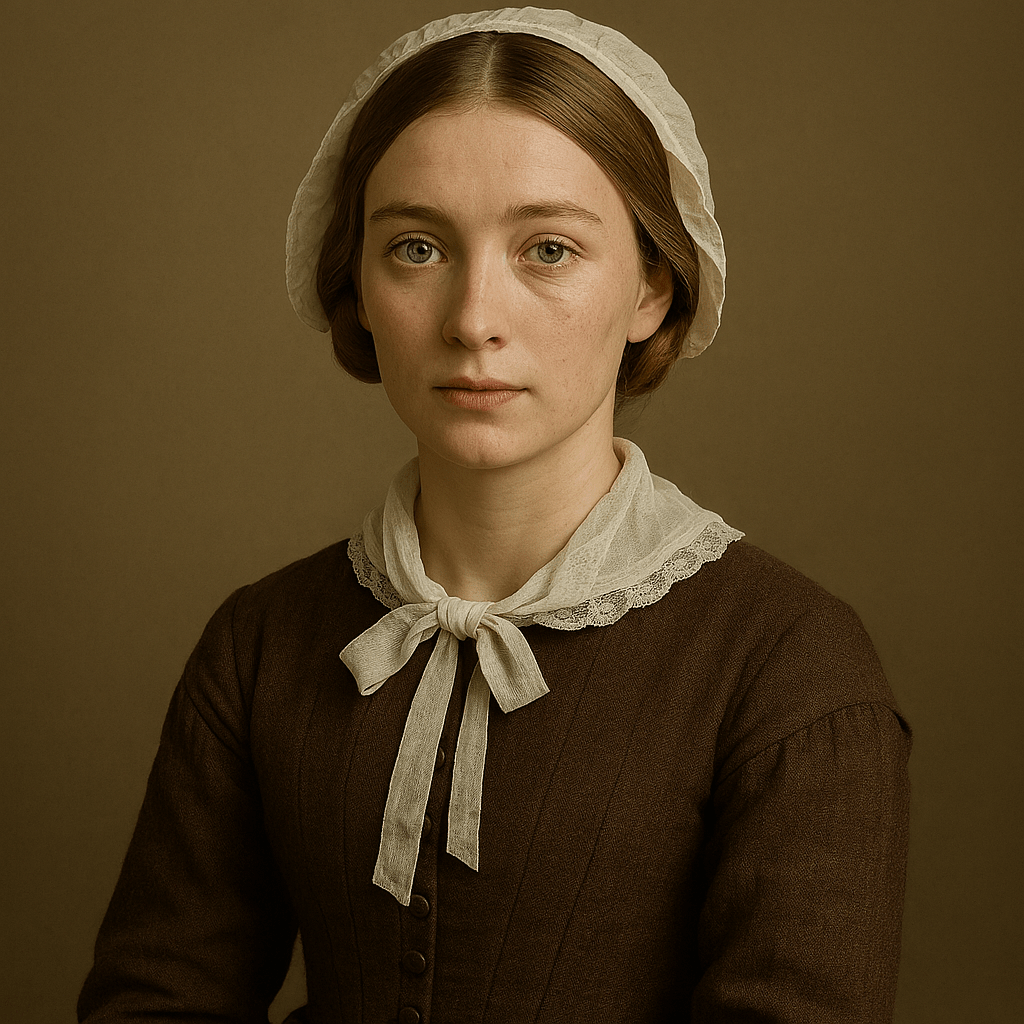

Mary Ann was only 33 years old at that time but had lived several lives already. Her family came to New South Wales in 1825 with her father, who served in the 57th Regiment, on board the convict ship Minstrel. In the following years, Mary Ann Connor would become Mary Ann McCann, flee to New Zealand to escape a conspiracy charge, lose her first husband, join the world’s oldest profession, marry again, and become the notorious Mary Ann Williams.

The Minstrel’s Child.

In May 1825, the surgeon on board the Minstrel [i] treated a 4-year-old child named Catherine Connor, the daughter of one of the soldiers who formed the ship’s guard. “This girl is of a very delicate constitution, being a twin,” noted the surgeon. The little girl had intestinal worms, fever, a swollen painful stomach, and was emaciated and pale. Her condition worsened until her death on 5 June 1825. “Read the Burial Service and committed the Body of the deceased to the deep,” noted the surgeon curtly, before returning to treat convicts with scurvy.

The Connor family now consisted of Private David Connor, his wife Margaret, sons Patrick and Dominic, and five-year-old Mary Ann. The Connors produced seven children in all, of whom only four survived. That seemed to be the lot of many families in the early 19th century. The Connors were not well-off, relying on David’s pay and rations, and travelling with his Regiment.

The Washerwoman’s Crime.

David Connor’s detachment was stationed in Sydney, and the family lived in rooms at the Barracks. In 1827, their final child, Margaret Ann was born.[ii] To keep the family fed and clothed, Margaret Connor worked as a washerwoman. One of the people she did laundry for was Mrs Margaret Pickever, a rather formidable shopkeeper in King Street.

On 3 June 1829, one of Mrs Pickever’s servants reported to her that she had seen another servant giving Margaret Connor a bundle of linen goods from the shop, without money changing hands. Mrs Pickever went to the police, then set out in determined pursuit of Margaret Connor, who, when located, still had the items in her possession. Mrs Pickever and a constable went to Margaret’s room at the Barracks and searched it in the presence of Drum Major Boyle. Margaret’s storage box contained several other items that Mrs Pickever identified as her property.

On Monday 14 September 1829, the matter came before Justice Stephen.[iii] Margaret protested that she had bought the goods from the store but called no witnesses. She was convicted of knowingly receiving stolen goods, and a week later was sentenced to 14 years’ transportation to Moreton Bay. This was a particularly harsh outcome for a woman with no previous convictions.

Moreton Bay.

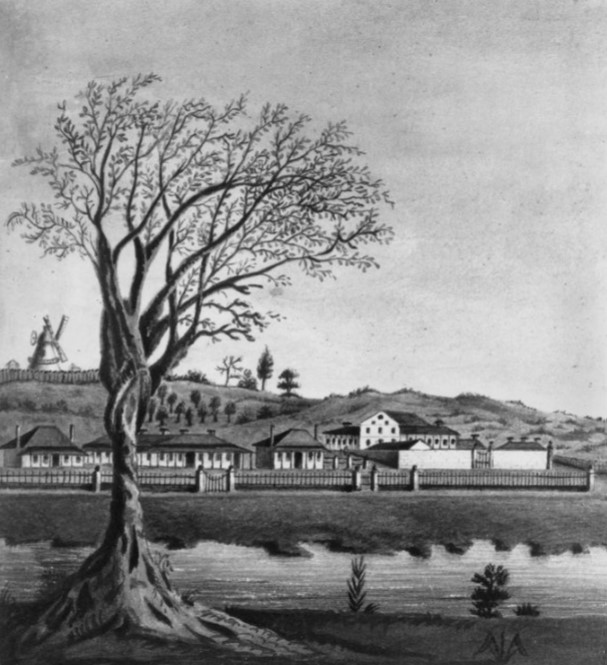

Margaret Connor began writing appeals to the Governor on the day she was sentenced, claiming that she received the property in ignorance that it had been stolen. The authorities were polite, but unmoved. On 6 January 1830, the Mary Elizabeth arrived at Moreton Bay with six female convicts, including Margaret Connor. She 35 years old, just below 5 feet 4 inches, with a sallow complexion, dark brown hair and hazel eyes.

Margaret’s first years at Moreton Bay would have been trying. Her children were 500 miles away. The Female Factory would not be finished for several months, and there were very few other female convicts about. Worse still, the settlement was under the control of Captain Logan’s detachment of the 57th Regiment. She would be serving a long sentence of transportation in the presence of her husband’s colleagues and their wives. At best, they would have pitied her. At worst, they would have humiliated her.

Margaret behaved herself at Moreton Bay, with a view to receiving a remission on her sentence and reuniting with her children. David Connor petitioned on her behalf in 1831, she petitioned in 1832, Mrs Margaret McDermott petitioned in 1835, and the Governor sought the views of the Commandants. Captain Clunie said no, but his successor, Captain Fyans, said absolutely. Margaret was returned to Sydney to a different world in November 1836.

The Orphan School and Brush Farm.

On 7 October 1829, just 18 days after Margaret’s sentencing, Private David Connor presented himself to the Trustees of the Orphan and applied for his daughters to be admitted. They were Mary Ann, 11 and Margaret Ann, 2. He could not, he stated, support them on his soldier’s salary. He had two sons, but he’d keep them with him. Perhaps sons were cheaper to maintain.

In July 1831, David Connor petitioned the Governor again for consideration for Margaret. His regiment was about to depart for Madras, and he was taking his two sons with him. Could His Excellency pardon Margaret so that she could take her daughters out of the school of industry, and the family could travel to India together? If not, could His Excellency arrange to have Margaret serve her sentence in Sydney, so that she might be able to visit her daughters occasionally? His Excellency asked for a report and Margaret’s case file but noted that the request “cannot be complied with.”

The following year, Mary Ann was put into the service of Mr Forster at Brush Farm, where she remained until her mother could return. Brush Farm, which still stands, was pioneering Australian viticulture in the 1830s. Presumably, Mary Ann worked in the household as a servant. Margaret Ann continued at the school of industry, where one suspects, trade skills and unpaid work took priority over education.

Mary Ann was seventeen when her mother returned to Sydney in 1836. The following year, she married a former convict named James McCann.[iv] James was 25 and a tailor by trade. His sentence expired in 1833, and he was a free man. The McCanns would have made a charming-looking couple. He had light brown hair, with grey-blue eyes and freckles. Mary Ann was slender and sandy blonde, with grey eyes and a fresh complexion. They saw eye to eye literally – both stood 5 feet 3 inches.

James and Mary Ann enjoyed a year or two of quiet married life in Sydney before alcohol-fuelled neighbourhood disputes brought them more trouble than they could have imagined.

“You’re no better than you should be, and you knows it.”

In August 1839, neighbourhood disagreements, which had been marinating in alcohol for some time, came to a head in the Parish of St Andrew, Sydney. Mary Ann McCann accused a John McPherson of stealing, after a slight directed at her friend, Mrs Lynch. John McPherson was arrested, with the McCanns and Lynches gave evidence against him. Fortunately for John McPherson, he was acquitted when two respectable witnesses testified that they saw and heard the two Marys vowing to accuse McPherson of theft.

The police began building a case against the McCanns and Lynches. Meanwhile, there was bad blood between the McPherson, Lynch and McCann families. The ladies of each family became very drunk, and fists and stones flew. An exasperated constable gave evidence of attending a drunken brawl between a group of women “making a riot,” and of dragging Mary Ann off with difficulty.

Mary Ann was charged with assault but clearly felt herself the victim in the situation. She pleaded to the court: -“It’s all spite, your Worships-it’s all a combination; here’s the gown she tore when I was saving Mrs. Lynch from her clutches, when she would have murdered her, and all because I prosecuted her brother-in-law.”

One of the witnesses told Mary Ann, “You’re no better than you should be, and you knows it.” Mary Ann, aged 20, replied proudly, “I’m a married woman I am, and that’s more than you are or ever will be, if the man knows you as well as I do.”

The Bench had no patience for any more shrewish exchanges and ordered Mary Ann to keep the peace for one year, with rather high sureties. “I won’t he bailed-I’m the victim of a base conspiracy. Everyone’s against me, but I won’t be bailed-I’ll go to gaol and so I will,” wailed Mary Ann as she was hauled off to the cells.

The sureties were steep, but the McCann and Lynch families had more to worry about, because in no time, they were charged with criminal conspiracy. In November 1839, they were bailed to the next sittings of the Sydney Supreme Court.

When the Court convened for their trial in February 1840, only Mary Lynch appeared to answer her bail. The McCanns had gone to New Zealand, she advised, but she expected that they would be back for trial at the next sessions. Mrs Lynch had her bail enlarged, and the police waited. In October 1840, a keen-eyed policeman noticed the name McCann in the passenger lists of incoming vessels from New Zealand, and arrested Mary Ann at her mother’s house in Market Street.

No mention was made of James McCann’s whereabouts, and he disappears from the public accounts of Mary Anne’s life at this point.[v] James McCann may have died after returning from New Zealand, or he may have died in New Zealand before October 1840. Mary Ann McCann was a widow when she remarried a few years later.

A Disorderly House.

The conspiracy case itself disappeared as well – the matter never reached the courts for hearing. Possibly, this had something to do with James’ absence. After 1840, Mary Ann was quiet for a couple of years. Then, she and her mother returned to the courts in circumstances of notoriety.

At this point, Mary Ann was a widow, and Margaret had long lost contact with her husband and adult sons. There was now no man to provide for the women, and they made their way as best they could. Working as servants hardly paid the bills.

In October 1842, Mary Ann was imprisoned for two months along with another lady who attended at the Police Office rather a lot. The charge was not specified, and Mary Ann was home for Christmas.

1843 was a troubled year for the Connor-McCann family. Mary Ann was back in custody in February, bailed to attend at the Police Office. In April, mother and daughter were charged and remanded in custody, awaiting trial for robbing a sailor in a brothel. By the time the case came to trial in July, the sailor had returned to his ship and sailed for ports unknown. No complainant meant that the charges were dismissed.

“Mr. Justice BURTON enquired, if the police authorities were aware whether either of the prisoners kept a brothel? Inspector Higgins replied that the younger of the females before the Court did so, and that it was in her house the robbery had been committed.”[vi]

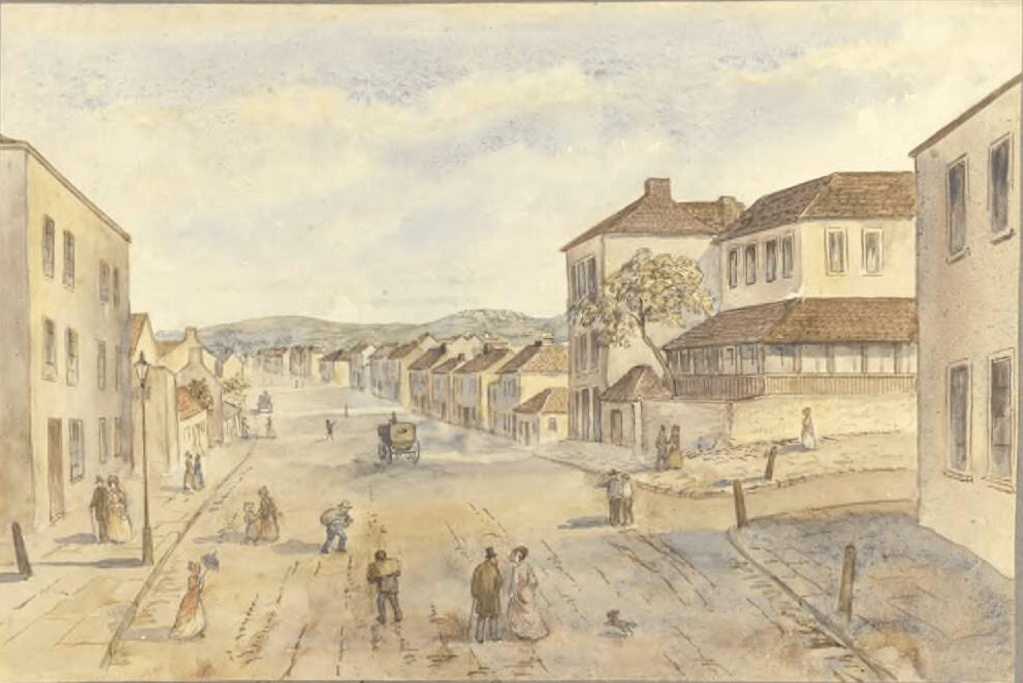

July 1843 was the last time in several years that we see Margaret Connor and Mary Ann McCann together. Somehow, in January 1844, Mary Ann McCann was in Brisbane Town at Moreton Bay and preparing to marry an English ticket-of-leave holder named George Williams.

Williams had been transported in 1830 as a teenager for stealing paper from the printer he worked for. He had borne a good character before the theft and proved to be a trustworthy and hardworking government servant. He went to Moreton Bay in 1841 in the service of George Mocatta.

George Williams moved to South Brisbane and was aged 33 in 1844. A 25-year-old widow named Mary McCann caught his eye. They were married on 01 February 1844 by Rev. John Gregor, according to the rites of the Church of England. (Mary Ann was quite flexible in matters of doctrine, declaring herself Protestant or Catholic when it suited her.)

How and why Mary Ann came to Brisbane at the dawn of free settlement is not recorded, but the Sydney newspapers at the time full of stories of servants and labourers who had been granted free passage to Moreton Bay to go into service, and had the temerity to work for themselves, or ask for slightly more than a pittance.[vii] I suspect that Sydney had become a little too “warm” for Mary Anne, and the chance of a free passage and a fresh start would have been appealing. Plus, the place was teeming with unattached men. Margaret, who had her own experience of Brisbane Town, remained in Sydney, drinking and getting arrested sporadically.

“A Fair Penitent.”

In June 1846, Brisbane got its first newspaper, and in November 1846, Mary Ann Williams made her first appearance in it. She was a “respectably dressed female” who, in the lockup after being arrested for drunkenness and disorderly conduct, “conducted herself in a manner quite unbecoming to her sex.” The unbecoming lady was fined 15 shillings.

Mary Ann was picked up for drunkenness several times in the following years. In February 1848, the exasperated Brisbane Magistrates sent her to Sydney Gaol for two months. The Courier’s report suggested that Mary Ann was back on the game. She had “of late been given to truant wanderings, and occasional fits of jollification at the public houses of South Brisbane, which were totally at a variance with the vows she made when the conjugal knot was tied.”

A FAIR PENITENT. – On Monday night last, Mary Ann Williams, being thereto instigated by sundry nobblers and deeper potations indulged in during the day, troubled the inhabitants of South Brisbane with an exhibition of her jovial qualities, by “flaring up” rather extensively in the public streets, in company with four or five gentlemen of her acquaintance.

Constable McGuire, feeling a laudable inclination to prevent so accomplished a lady from wasting her sweetness on the desert air, obligingly invited her to take possession of an apartment in Ossory Castle[viii], which he had sufficient influence to offer for her acceptance.

After considerable pressing, the suggestion was acceded to, and the consequence was a presentation at the Police-office on the following morning. Mrs. Williams – glowing with the effects of the previous night’s recreation, and looking about as wholesome as a Tartar with the scurvy – tried the pathetic, accompanied by an eloquent glance towards the Bench, and which seemed to be intended for the peculiar benefit of Mr. M’Connel; but, whatever the mere man may have felt, the magistrate was inflexible.

It was borne in fatal remembrance that Mary Ann had recently returned from an involuntary residence of three months in the neighbourhood of Woolloomooloo[ix], and that she had since visited the Police-office upon an occasion similar to the present. It was therefore arranged, that she should have the option of making a donation of 21s., to be applied as directed by law, or secluding herself from an admiring public for forty-eight hours, in a place to be provided for that purpose; and abstaining in the meantime from animal fool and artificial liquids.[x]

Moreton Bay Courier, 1849.

Several spectacular arrests followed, usually involving constables trying to keep Mary Ann from jumping from the ferry to the watchhouse. Mary Ann was of a dainty build, but that was all that was dainty about her.

George Williams, solidly well-behaved and now in possession of a conditional pardon, grew exasperated with his wife. Their neighbours were tired of her foul-mouthed abuse and drunken threats. In 1851, George had to use physical force to stop Mary Ann beating a neighbour with a rock.

Mary Ann was by now an alcoholic and was probably suffering from mental illness. This is borne out by an incident in October 1851. Mary Ann had stolen some items from a neighbour, and when George apologetically returned them, his wife destroyed their household furniture and belongings in a fit of rage. George gave her in charge of the police. In the lock-up that night, Mary Ann attempted to end her life twice[xi]. On the second occasion, she was so determined to self-harm, that she managed to get her arm out of a straitjacket. The police saved her, and she was admitted to Brisbane Hospital to recover. When she was able to face court, she was committed to take her trial for stealing.

George Williams decided to separate from his wife. He engaged the future Crown Solicitor, Robert Little, to work out terms for a formal separation and maintenance agreement. In February 1852, he advertised the fact in the Courier’s public notices, stating that she had a separate maintenance, and that he would not be responsible for any of her debts. (Usually, men in these circumstances did not make a formal legal agreement, and any advertisements published about debts involve the use of terms like “has left my house without my permission.” It was exceedingly rare to admit to a formal separation in those conservative times.) A week later, Mary Ann was gaoled for a month at Brisbane for obscene language and indecent conduct.

Mary Ann was released in late March 1852, and her estranged husband was out of town. Following an accusation that she had (again) stolen linen from a neighbour, the police searched the former marital home. Mary Ann was not officially residing there, but there was evidence that she had slept there recently. The stolen linen was found, as well as “a little girl, six years old, who was adopted by the prisoner.” Whoever that little girl was, I hope that she was taken care of by either George Williams or sent to the Benevolent Society.

Mary Ann, while waiting to be dealt with for the thefts, consoled herself in the usual manner, and was placed in the lockup overnight. There, she called upon the turnkey to make a complaint against the Bay fisherman, Timothy Duffy, accusing him of stealing property from the house of Robert Little, whom she’d consulted on matters of her maintenance.

Duffy was a straightforward ticket-of-leave man, who never advanced beyond Mr Little’s front hallway, appearing there only to sell fish. He had an alibi and could prove his innocence. After dismissing the charge against Duffy, the Bench committed Mary Ann to trial for the theft.

In Mary Ann’s case, several witnesses were able to prove her guilt for the theft. The most unlikely, but ultimately rather compelling, was Ellen Semple (Ellen the Cutter). Mrs Semple had shared a gaol cell with Mary Ann and was able to testify that a handkerchief that formed part of the stolen goods was brought into the gaol with some tea and sugar by – Mary Ann’s mother, Margaret. Ellen had seen the handkerchief, which had a particular burn and cut mark. Margaret Connor had evidently moved to Brisbane following a series of arrests in New South Wales.

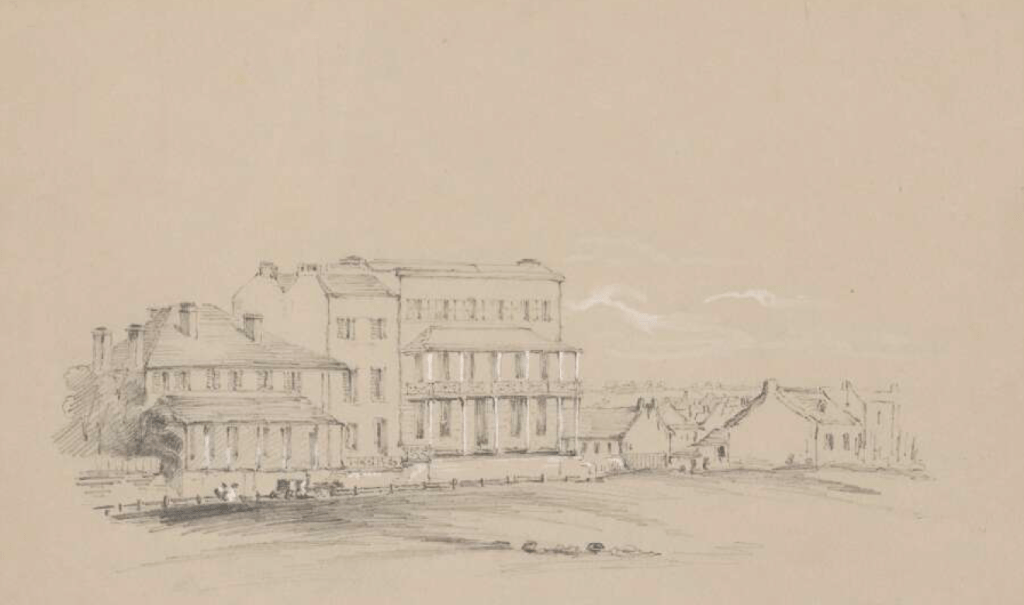

The jury found Mary Ann guilty and Justice Alfred Stephens, the son of the Justice Stephens who had sentenced Margaret 23 years earlier, gave Mary Ann a character assessment, together with three years’ imprisonment in Parramatta Gaol, with the first 14 days of the first four months in solitary confinement.

The Courier reported him telling Mary Ann that she “stood before him so deeply steeped in crime that she appeared a hopelessly abandoned wretch.” Stephens expressed strong reservations about her prospects for reform and suggested that if she continued to lead the life she had been leading, her final judgement would not be far off. As Mary Ann was wrestled out of the courtroom, “she made some disgustingly offensive gestures to the police.”

The Vanishing.

Mary Ann Williams was admitted to Parramatta Gaol after processing at Darlinghurst in 1852. She rebelled at first, particularly with the alternating fortnights in solitary. By 1854, she had calmed down, and probably dried out, enough to appeal to the Governor for a remission of her sentence. She wrote a petition, highlighting her respectable origins as a member of a military family, who had come free to the colony. She expressed regret for her offences and prayed that His Excellency would see fit to commute the remaining eleven months of her term.

The Colonial Secretary’s Office referred the question to Sir Alfred Stephen, who replied, with a lot of underlining:

“I will simply copy my note on this abominable woman’s case – made at the time of her conviction. It is to be hoped that she will endure every hour of her sentence, and that the Visiting Justice may see this memorandum.

“The Prisoner is an atrocious character. Within 4 ½ years she has been thrice charged with robbery, and once convicted of larceny, twice convicted of assaults, and several times of drunkenness and obscenity: – in the whole having been before the Police 17 times. To which I must add that in the case before me she was guilty of perjury – having, to save herself, actually sworn that the crime she was charged with was committed by a third person – who clearly (most clearly) proved an alibi, and the stolen articles were found within a few hours after they were taken, wrapped up in her own handkerchief!” Alfred Stephens. 17 October 1854.

The Colonial Secretary noted the file: “Under these circumstances, no remission can be allowed.” Mary Ann did her stretch.

While she was still in Parramatta, her mother entered Brisbane Gaol to serve 24 hours in lieu of bail for drunkenness. Then, on 1 April 1852, the Courier reported that an inquest was held on the body of an old woman who had dropped dead suddenly in Stanley Street, South Brisbane. Her name was Margaret Connor, and her demise had been hastened by excessive drinking.

Mary Ann Williams was released from Parramatta in April 1855. What happened to her then is a mystery. A Mary Ann McCann was admitted to Darlinghurst in 1856, but her name and description don’t match the Minstrel Mary Ann. A Mary Ann Williams was imprisoned in Goulburn in 1858 for theft, but this woman was shorter, stout and had black hair.

Seven other Mary Ann Williamses were imprisoned on various occasions between 1855 and 1860, but they were from other ships and bore other descriptions and ages. (I’m quite sure. I made a spreadsheet. Or two.)

In April 1857, a Mary Ann Williams with no particulars to identify her as Minstrel Mary Ann, was badly beaten by a couple of rather aged women of ill fame. This lady received very serious injuries. Other Mary Anns were taken to Tarban Creek asylum but had no other information to identify them. A Mary Ann Williams passed away in Tarban Creek Asylum in October 1866. Her age and identifying details were not noted.

The most likely, or least unlikely, candidate is a Mary Ann Williams who died in 1856 (date unspecified) in Sydney, New South Wales. On the Australian Death Index record, her parents are recorded as “Daniel” and Margaret.

George Williams vanished from the public records in Brisbane, either by accident or design, after 1852. It’s a common enough name, and he was officially a free man. If Mary Ann died in 1856, he may be the bookbinding George Williams who married at Dalby a couple of years later. George Williams might have remained at South Brisbane, quietly living his life. He might have left Brisbane after Mary Ann’s final trial. It would be hard to blame him if he had.

[i]Also on board the Minstrel were a few famous convicts. James Davis, “Duramboi” lived with the indigenous people for 14 years, returning to Brisbane to become a blacksmith, interpreter and merchant. Henry Herring managed to be transported to Australia twice – initially in 1815, then in 1825. He picked the pocket of the Earl of Normanton to earn his first voyage and was found to be illegally in the United Kingdom and under strong suspicion of highway robbery to earn his second voyage. Edward Coulthurst, transported for life in 1825, was convicted of killing an indigenous child in 1826, then was executed in 1827 for piratically seizing the brig Wellington on its voyage to Norfolk Island. He had been in Australia for less than 2 years and was barely 20 years old.

[ii] For clarity, I will refer to the mother as Margaret Connor and the child born in 1827 as Margaret Ann.

[iii] This was the redoubtable Justice John Stephen, father of Sir Alfred Stephen, before whom Mary Ann appeared in 1852.

[iv] James (or John) McCann was born in County Meath in 1811 and was convicted and transported on the Cambridge in 1827 (aged 16) for stealing sheep. He was sentenced to 7 years. For clarity, I will refer to him as James.

[v] A John McCann was buried at Liverpool in February 1840, and appears to have a similar birth date, but no other particulars.

[vi] The records of Darlinghurst Gaol show that Margaret Connor was born in 1793, making Mary Ann the younger of the two women, and clearing any confusion that Margaret Ann might have been the Margaret arrested.

[vii] “The Colonial Secretary on Wednesday, told in council a story of one Lynch, a shoemaker, who was sent to Moreton Bay at public expense; but when he got there, he set up a store; and told another anecdote of a young lady, who must be sought for, &c.” Sydney Chronicle, December 1843. (London to a brick the young lady was Mary Ann.)

[viii] Also known as Queen Street Gaol.

[ix] Darlinghurst Gaol.

[x] 48 hours in solitary confinement on bread and water.

[xi] Given the sensitivity to descriptions of these matters, I won’t mention what she did to herself.

1 Comment