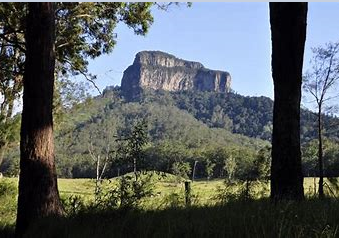

On the morning of 31 May 1840 the surveying party run by Assistant Surveyor Stapylton was camped in the bush near Mount Lindesay in South East Queensland.

The Assistant Surveyor was an English gentleman of 40 named Granville William Chetwynd Stapylton, youngest son of a very grand family, and grandson of the 4th Viscount Chetwynd. He’d had a varied career as a Surveyor in the Colonies – he had much ability, but his drinking would see him dismissed from the service of Robert Hoddle in Port Phillip in 1838. An opportunity to work for Robert Dixon in the largely unexplored area around Moreton Bay brought him to the Mount Lindesay area in 1840.

(Mount Lindesay would be an area much given to exploration by grand-sounding individuals. In 1872, the first European to climb it would be a gentleman named Thomas de Montmorency Murray-Prior, followed 18 years later by Carsten Egeburg Borchgrevink and Edwin Villiers-Brown.)

Accompanying Stapylton was a party of seven convicts working for the Surveyor-General’s Department, a team of bullocks and dray and boxes of luggage and supplies. Several indigenous men had been with the surveying party for all or part of the previous ten days.

At 8 o’clock that morning Mr Stapylton, dressed for the day’s explorations in trowsers, shirt and black cloth waistcoat, ordered four of the men to make a passage over a nearby creek, so that the bullocks and dray could be brought over. He wanted to set up camp on the other side that evening.

The men he chose to go to the creek were Abel Sutton, Peter Finnegan, Patrick Kelly and William Gough, and they left sharpish, knowing Mr Stapylton to be a taskmaster. Three convicts remained at the tents with Mr Stapylton. William Tuck, at 49 the oldest on the expedition, was in his tent, resting a sore leg. James Dunlop was in charge of the bullocks, and William Burbury was getting Mr Stapylton’s breakfast.

The five indigenous men present early that morning included three men known to the party as Merridio, Carbon Bob and Bogee. The other two men were only known to the white men by sight. Merridio had his son, a boy about 12, with him, and Bogee had a toddler with him. There were no indigenous women with the party, and Merridio was the only person who had stayed with the party for the whole of the expedition.

William Burbury finished serving up the breakfast at 9 o’clock, and Mr Stapylton ordered him to go and assist with the party at the creek. As he was leaving, Burbury noticed that three of the indigenous men and the children had left the area, leaving Merridio and Carbon Bob at the camp.

James Dunlop saw Mr Stapylton sitting just inside his tent making his notes, he made endless notes, that man. Tuck was still laid up with his leg and he (James Dunlop) was tending to the bullocks when he noticed that four indigenous men, including Bogee, had joined Merridio and Carbon Bob, and some of these men had spears. Carbon Bob and one of the other men followed Dunlop up a slope, and he was beginning to feel uneasy. He saw Bogee head towards Mr Stapylton’s tent, and two other men approaching William Tuck’s tent.

Dunlop turned slightly to see Carbon Bob’s companion throw a spear at him. Missed. Thank God. Then Carbon Bob struck Dunlop on the head with a waddy, and the world went black. He didn’t know how long he was out, but as he struggled back to the camp, he saw a shocking sight – William Tuck and Mr Stapylton both lying dead. There were no aborigines about by then.

Weak and confused, Dunlop lay down on a tarpaulin near Tuck’s body. Perhaps the crew out at the creek would come back to help him. He might have dozed. The next thing he knew, the indigenous people had come back in numbers, and were stripping the bodies, and breaking open the boxes of supplies. Whether the men working at the creek had come back, Dunlop wasn’t sure. Time went all over the place.

Carbon Bob came over to where Dunlop was lying and started to finish him off. Dunlop rolled the dice and called out to Merridio that Carbon Bob was trying to strip him. Merridio came to the tarpaulin and stopped Carbon Bob’s attack. He knelt by Dunlop and told him to go up to the fires, they would get him something to eat. Dunlop tried to stand, and Merridio put his arm around Dunlop’s waist and tried to help him up, but it was no use. Dunlop’s legs gave out, and Merridio left him at the tarpaulin. He blacked out.

At midday, Abel Sutton, Peter Finnegan, Pat Kelly, William Gough and William Burbury were finished their creek crossing, and coming back to camp. The first thing they saw was James Dunlop lying bloody and apparently near death on a tarpaulin. Things seemed to be a shambles, and they wondered why Tuck and Mr Stapylton were not stirring about, particularly with the poor fellow Dunlop hurt so badly.

Abel Sutton went to Tuck’s tent, and found the man dead and covered in blood, with a large cut to the side of his neck. He thought it looked like a spear wound. He called to the men that Tuck was murdered.

Patrick Kelly, fearing the worst, went to Mr Stapylton’s tent. It was a terrible sight. Stapylton had a severe wound to his breast and right arm. One of Stapylton’s eyes was so badly injured that it was swollen and nearly knocked out of its socket. The other eye was open. Stapylton had been stripped and was partly covered with a tarpaulin. Kelly found his voice and called out to the others that the Master was killed and to find their guns and ammunition or they would all be murdered. Who knew if the killers were still about?

Gough and the other men looked around for the arms, but all of the luggage boxes they had brought were broken open and ransacked. There were no guns, nothing to eat, no clothes left. They decided to clear out on foot, taking what they could to defend and feed themselves – a cutlass, a billhook, a tomahawk and a small bag of rice. They thought poor Dunlop was at his end, and they couldn’t travel as quickly with a man so injured. They would make for the station at Coopers Plains and get help.

The fear of God was in them, so they made about 20 miles the first day, 40 the next, and the last 15 miles saw them get in to Coopers Plains on Tuesday 2nd June 1840.

Richard Allen, overseer at Coopers Plains Government Station, was a man of action. He sent a man on horseback to inform the Commandant at Brisbane Town and set about accommodating and feeding the exhausted men.

Meanwhile, at the camp near Mount Lindesay, James Dunlop hovered between painful consciousness and death. At some point, the indigenous men had destroyed the rest of the camp, and Mr Stapylton and Tuck had been put on the fire. There was not much left of the Master. Thinking to get away, Dunlop dragged himself up into the mountains. He didn’t know when it was, but he heard an axe strike a tree. Perhaps it was Surveyor Dixon’s party. He cried out for help. He heard a cooee. Then up popped Constable Thompson, Doctor Ballow and the Commandant himself, Lieutenant Gorman, all looking as shocked as he felt to see them. They had been told that they would find three dead men in the bush, but here was Dunlop, weak and clinging to life. It was Saturday the 6th of June, and Dunlop had been in the bush injured since the previous Sunday.

Doctor Ballow noticed a severe head wound and injuries about Dunlop’s upper body, and the exhausted state the man was in, and brought him to the camp the Commandant had set up. To everyone’s relief, James Dunlop began to respond to his treatment and recover.

The next day, Sunday 7th June 1840, the Commandant’s party reached Stapylton’s campsite. Lt. Gorman had already taken the depositions of the five men at Coopers Plains before travelling to the campsite, so he had some idea of what to expect.

The search party found part of Stapylton’s skeleton, which appeared to have been cooked and gnawed at, they did not know whether by people or native dogs (dingoes). His skull was lying a few feet away, and the identified it by the colour of the hair left on it. William Tuck was lying face down on an extinguished fire, decomposing and attacked by animal predators.

The Commandant began an inquest immediately on the bodies, recording in the Book of Trials the date and place: Mr Stapylton’s last camp in the Bush about 14 miles East by South of Mount Lindsay this 7th day of June 1840.

Evidence was taken from all the surviving convicts, except Dunlop, who was too ill to return to the campsite. Each man identified the bodies and deposed to their recollections of the indigenous men who had been at the tents on the 31st of May.

William Tuck’s body was too far gone to take back to Brisbane Town, and besides he was a convict, so the party buried him at the campsite. The skeletal remains of Mr Stapylton were sealed in a box and taken to Brisbane Town for interment. All parties were glad to leave the place.

To be continued in Part 2.

Sources:

Book of Trials Held at Moreton Bay, 1835-1842. Item ID 869682, State Archives of Queensland.

Louis R. Cranfield: Stapylton, Granville William Chetwynd (1800 – 1840), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, Volume 2, (MUP), 1967.

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842), Saturday 29 August 1840, page 2

Photos: antiquaprintgallery.com (first image), panoramio.com (second image).

wonderful history!

LikeLike