On June 15 1840 Dr Ballow gave his report on oath to Commandant Gorman, and a week later, having reviewed the evidence thus far, Gorman issued an order to apprehend the men believed to be responsible for the deaths of Stapylton and Tuck, and the attempted murder of Dunlop.

Colony of New South Wales, to wit.

Brisbane Town Moreton Bay this 22nd day of June in the year of our Lord 1840.

Whereas the five aboriginal natives named and described as follows stand charged upon oath before me Owen Gorman Esquire, one of Her Majesty’s Justices of the Peace for the said Colony with the murder of the late Granville Chetwynd Stapylton, an Assistant Surveyor in the Surveyor General’s Department of the aforesaid Colony, and the late Prisoner of the Crown William Tuck “Portsea” near Mount Lindsay in the district of Moreton Bay on the 31st of May in the year aforesaid.

No. 1: Carbon Bob. About 25 years of age and about 5 feet 7 inches high. The great toe of his right foot turned very much towards the left, with the two next toes deformed and turned a little towards the great toe.

No. 2: Merry Dio. About 32 years of age and about 5 feet 5 inches high with a broad face and sulky look.

No. 3: Bogee. A stout man about 26 years of age and about 5 feet 7 inches high, his left eye very sore and disfigured.

No. 4: A smart black man name unknown about 25 years of age and about 5 feet 5 inches high who appears to want a tooth or open space between the teeth in the front part of his mouth.

No. 5: A straight smart black man about 26 years of age and about 5 feet 9 inches high. Name unknown.

This is to direct and require that all Constables and others Her Majesty’s subjects to use their utmost exertions to apprehend each and all of the persons described aforesaid and bring thereto any of them before me at Brisbane Town and for so doing this shall be your sufficient Warrant and Authority.

Given under my hand and seal at Brisbane Town in the District of Moreton bay the day and year aforesaid. Signed, Owen Gorman, JP.

He then added thoughtfully:

As a reward for the apprehension of any of the abovementioned aboriginal natives, I do hereby promise that I will use my utmost endeavours to obtain through His Excellency the Governor a remission of sentence or a Conditional Pardon for any Prisoner of the Crown who may bring to Justice any or all of these persons. Signed, Owen Gorman, JP.

That ought to do it. Stapylton was a difficult man in life, but no Englishman deserved to die that way. Only weeks before, Gorman reflected, he had been run ragged conducting trials of the convicts who had managed to irritate Stapylton in the course of previous expeditions. As if he didn’t have a settlement to run.

Granville William Chetwynd Stapylton was interred in the North Brisbane cemetery, now E.E. McCormick place, with as much ceremony as the small settlement could muster. His aristocratic status and terrible death made him seem a martyr to early Brisbane Town. There was great concern when the old cemetery was closed and the land sold off – would his grave go unmarked, or be built over? Fortunately, the council heard these concerns, and his grave was relocated to the General Cemetery at Toowong, where his memorial ID is 76186875.

By the 10th of July, Gorman had his men, or at least some of his men. He sent Constable Thompson and a well-armed party of eight men (including some survivors of the Stapylton camp) back to the Mount Lindesay area to locate, identify and capture the killers. They found three indigenous men that Pat Kelly, William Gough and William Burbury identified as having been at the Stapylton camp that day and found items of clothing and other kit on them that came from the dead men.

A committal hearing was held at Brisbane on the 10th of July 1840. A prisoner named Peter Glen was sworn in to interpret the proceedings to the indigenous men. The Court heard that William Burbury was sure that the three men before the Court – named as Merridio, Nengavil and Birramatta – were at the Stapylton camp on the day of the murders, and was able to identify Stapylton’s black cloth waistcoat, shirt, knife and other items in Merridio’s possession.

Abel Sutton was also positive in his identification of the three men before the Court. James Dunlop was only able to swear to his being hit on the head with a waddy by Carbon Bob, who was not present. Peter Finnegan maintained that he could swear to the identity of the aborigines at Mount Lindesay on 31st May but was positive that none of the men in the dock had been at the camp. Any further evidence of Patrick Kelly and William Gough was not recorded in the Trial Book for Moreton Bay.

Merridio, Nengavil and Birramatta were committed to take their trial at the Supreme Court in Sydney and were forwarded there in February 1841. Perhaps there were further investigations made at Moreton Bay before the Crown was ready to make its case, but that was an unusual delay from committal to being sent to Sydney. None of the three accused had ever seen a town or city before – Brisbane Town was a few barracks and some houses – this place had hundreds of white men and women walking around free, and numerous large buildings. The building they got to see most of was of course, the prison.

Three men arrived at Sydney Gaol, but by the time of the hearing three months later, Birramatta had died in custody.

Merridio and Nengavil faced the Supreme Court together in May 1841, charged in relation to the murder of William Tuck. They were alternatively charged as accessories, a move that showed that the Attorney-General had concerns with the identification of the offenders, and the strength of the eyewitness evidence.

This time, their interpreter was John Sterry Baker, or Boraltchou, who had escaped the Moreton Bay settlement in 1826 and lived with the indigenous people of the Region until in August 1840, when he surrendered to the Commandant. Unclothed, deeply tanned and unshaven, Baker managed to recover enough English to identify himself to an astonished Gorman, who ordered the oldest Chronological Register to be dusted off and examined to see if this strange fellow was telling the truth. He was. Since then, Baker had interpreted for the Crown, while the Crown figured out what to do with him.

Legal argument took up the first part of the hearing. Mr Cheeke, for the defence, sought directions as to whether the defendants should be tried by a jury of at least half of their peers – that is, indigenous people, who spoke the language and knew their customs. Cheeke also sought rulings on the applicability of English law to the men, who could have no knowledge of it.

The Bench rather testily replied that these questions had been raised and disposed of before. There was precedent , which made Merridio and Nengavil British subjects, thank you very much, and subject to the same laws and penalties.

While all of this was being argued, and Sterry Baker no doubt trying to impart the meaning of their Britishness to the men, Merridio made a request. His name was not Merridio, he explained, it was Mullan.

The prosecution witnesses gave their accounts of the day of the murders and the capture of Mullan and Nengavil. Abel Sutton remained convinced that the men in the dock were two of the men at the camp on the 31st of May 1840, William Gough agreed, as did Pat Kelly.

James Dunlop, the only member of the surveying party to be present during the attack, denied knowing the prisoners, and on cross-examination, denied receiving food from the aborigines over the six days following the killings.

Cross-examined.- Neither of the prisoners at the bar was Merrydio nor Carbon Bob, nor Bogee. Witness never saw the old man at the bar before the Friday after the murder was committed. Merrydio and that old man were both there together.

By the Attorney General.- Witness considered that but for Merrydio Carbon Bob would have put him on the fire. He thought he owed his life to him, but he would not on that account favour Merrydio. The prisoner at the bar was not him.

Dr Ballow gave his evidence on the injuries of the dead men, and of the condition of James Dunlop when found on the 6th of June. On cross-examination, he asserted that Dunlop could well have survived those days alone. As for Dunlop, he had the meagrims in his head, so he couldn’t elaborate. Peter Finnegan gave evidence that neither prisoner had been at the camp on 31st of May 1840.

The Judge summed up, pointing out that there was genuine conflict in the evidence about the identity of the prisoners. The jury deliberated, and gave guilty verdicts. As the Judge put on the black cloth and ordered Mullan and Nengavil to die, Sterry Baker frantically interpreted the result to the prisoners. Their response, translated back to the Court, was “What of it? Let them hang us!”

And so it eventually came to pass. Mullan and Nengavil were taken from Sydney Gaol in those heavy chains the white men kept putting on them, and sailed back to Brisbane Town with a fellow called Mr Keck. There they were put in the Gaol they’d been in earlier to await whatever ‘hanging’ meant. They weren’t to know that Mr Keck had forgotten to take the Warrants of Execution with him when he escorted the prisoners to Brisbane. Gorman considered the cost of sending another vessel to Sydney and back, and privately wished Mr Keck could be strung up alongside the aborigines. This sentiment increased when Mr Keck’s omission was reported in the Sydney papers.

Eventually the paperwork came, and the second execution in Queensland’s history was carried out. Mr Petrie, the Superintendent of Works, was directed to create a scaffold on the Windmill at Spring Hill, as public a place as possible. The idea was to make the deaths of Mullan and Nengavil an example to the local indigenous people. This is what happens when you kill a white man. Never mind that we’ve been shooting you in our cornfields for years. That doesn’t count.

Accounts of the hanging describe Nengavil as weeping copiously, and Mullan only becoming downcast when he realised what was to be done to him. Others noted that about one hundred local aborigines watched in silence.

A cheeky old convict decided to give 10 year old Tom Petrie (son of the Superintendent of Works) a fright by uncovering the face of one the prisoners in their coffins. He succeeded. Even as an old man, Petrie could recall the horror and pity he felt.

Sources:

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Saturday 29 August 1840 p2

Sydney Herald, Wednesday 2 September 1840 p2

Sydney Herald, Saturday 15 May 1841 p2

Australasian Chronicle, Saturday 15 May 1841 p2

Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertisers, Tuesday 22 June 1841 p2

Sydney Herald, Monday 26 July 1841 p2

Sydney Herald, Tuesday 27 July 1841 p2

Tom Petrie’s Reminisces of Early Queensland (Dating from 1837), Constance Campbell Petrie, Watson, Ferguson & Co, Brisbane 1904, pp245

Book of Trials Held at Moreton Bay, 1835-1842 Item ID869682, State Archives of Queensland

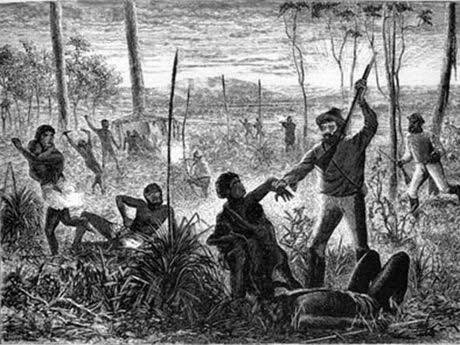

Image: Wikipedia

Could you give me the citation for the translated response of “What of it? Let them hang us”?

LikeLike

Hello Archie, it was reported by the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803-1842) Tue 18 May 1841, Page 2. Law Intelligence – Supreme Court. Frustratingly, the report doesn’t indicate whether the indigenous men said this in language, and had it translated to the Court by Baker, or whether they said this in English (unlikely I suspect).

LikeLike

My ancestor was killed by Aboriginal people at Mount Lindesay in 1845. A reprisal?

LikeLike