In my recent posts on James “Duramboi” Davis, I have referred in passing to David Bracewell (sometimes called Bracefell or Bracefield), known as “Wandi” to the indigenous people of Eumundi. I think now is perhaps a good time to fill in the details.

David Bracewell was born in Shadwell, London in 1805 and worked as a sailor and labourer, acquiring some impressive tattoos and a tendency to get into strife. Shadwell at the beginning of the 19th century was gradually turning from a prosperous port borough to a dockside slum, “Seamen, watermen and lightermen, coalheavers and shopkeepers, and ropemakers, coopers, carpenters and smiths, lived in small lathe and plaster or weatherboard houses, two stories and a garret high, with one room on each floor”. In 1794, a vast fire had consumed many houses along the Ratcliff Highway, and the area experienced industrial and racial violence at the time of David Bracewell’s birth. All in all, it was an ideal place to get into some serious trouble with the law.

At 21, Bracewell was 5 ft 6, with brown hair, a fresh complexion and grey eyes, and sported the tattoos “M. Rowe”, “AC”, “JC”, “CC” inside his right arm, and “Elizabeth” inside his left arm. Whoever Elizabeth was, Bracewell’s criminal activities meant that he would never see her again.

14 September 1826 Old Bailey:

DAVID BRACEWELL was indicted for feloniously assaulting William McKenzie, on the 1st of August, with intent, 1 watch, value 20s., from his person, violently and feloniously to steal. SECOND COUNT, stating his intent to be to rob him.

WILLIAM McKenzie. I am a seaman, and live in Pear tree-court, Ratcliff-highway. On the 31st of July I was going home, about twelve o’clock at night: I found the gate shut, and could not get in; I went and stood in the middle of the street for the gate to be opened; the prisoner came and asked me twice if I did not want a lodging; I said No; he asked me a third time, and I told him to go along – he then ran with his full force against me, and pushed me down, struck me on the chest, and got hold of the ribbon of my watch; he very nearly got it, but I prevented it – I then felt his hand in my pocket; I heard the watchman coming – he then took to his heels, and ran off – the watchman followed, and took him; I lost sight of him, but I am sure he is the person.

WILLIAM PHILLIPS. I am the watchman. On the 1st of August I took the prisoner, between twelve and one o’clock – McKenzie was in the road, and nobody near him – he was so alarmed and hurt he could hardly speak – he said he should know the man, and pointed which way he ran; I could not see him, but in a short time another watchman was driving the prisoner along, and desired me to see him out of the parish, as he was a bad character; I took him to the watch-house, and fetched McKenzie to the watch-house – he immediately said he was the man; there was nobody else near – McKenzie had been drinking, but was not intoxicated.

Prisoner’s defence. There were two watchman driving me about; I was taken to the watch-house; he said to the prosecutor, “That is the man, is it not?”

GUILTY. Aged 21. Transported for Fourteen Years.

Bracewell, and a group of other convicts deemed by the Secretary of State to be of such bad character that they would be sent directly to Norfolk Island, left England on the convict ship “Layton” on 13 June 1826.

In the nine months young Bracewell had spent in pre-transportation custody, he had not impressed the Superintendent of the hulks – the report stated that he was a bad character, who had been in gaol before, was mutinous and “a very bad fellow”.

On 09 October 1827, the Layton arrived in Van Diemen’s Land, with its 160 prisoners including 54 lifers. The Norfolk Island seven were split up, with three going to Moreton Bay – David Bracewell, William Clarke and Walter Cook. The Chronological Register notes his arrival per the brig Governor Phillip on 18 January 1828 with the following: “Ordered by the Secretary of State to be sent to Norfolk Island but His Excellency the Governor has been pleased to reverse that order, and to direct their being sent to Moreton Bay during their respective sentences.”

Bracewell became prisoner #591 of the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement, and he didn’t like it one little bit. Captain Logan was the Commandant in 1828, and Bracewell always gave as his reason for absconding the harsh treatment of prisoners by Logan’s men.

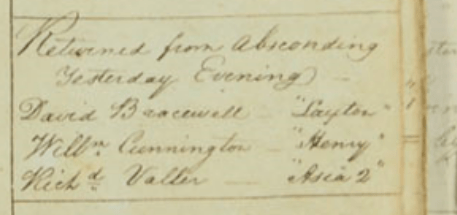

Spicer’s Diary of 15 May 1828 notes:

He didn’t last long, and four days later, Spicer duly noted:

Appearing before Commandant (and Magistrate) Logan, Bracewell felt the full force of the famous convict discipline, along with several others.

Bracewell bided his time, waiting until August the following year to make another run for it. This time he lasted a month, returning to the same treatment. Still, he’d made it a whole month.

He buckled down and endured two more years under Logan before escaping again on 01 February 1831. This time, he was away for six years.

Bracewell was one of the escapees who was accepted by the local indigenous people, and learned their languages and customs, acquiring along the way the name Wandi (which may or may not mean “big talker” – I like to think it did).

Bracewell lived among Eumundi’s people on what is now the Sunshine Coast – about 90 kilometres north of Brisbane and claimed to have spent three years on what was shortly to become known as Fraser Island, due to the 1836 wreck of the Stirling Castle under Captain Fraser near that place.

Indeed, years after the fact, Wandi/Bracewell claimed to have had quite a lot to do with the survivors of that shipwreck, including the famous castaway, Eliza Fraser.

In May 1836, the brig Stirling Castle, bound for Singapore, ran aground off the Queensland Coast. Captain James Fraser and his heavily pregnant wife, with members of their crew took to a longboat to get away from the rough seas, and to hopefully find a safe place to land. Several crew members died, Eliza’s baby was stillborn, and the survivors became separated. Some of the crew set out to walk overland, and others found themselves on the large sandy island with the local indigenous people. The Frasers believed that they were held captive and tormented by the aborigines, the descendants of the Fraser Island aborigines believed that their ancestors were welcoming the Europeans into their community and their shared system of work. Captain Fraser died on the island, either from overwork, injury or murder (depending on the account and the teller) and may have been partially eaten (see qualifiers above).

On 08 August 1836, a young Lieutenant named Charles Otter, from the Moreton Bay penal colony was surveying (shooting at wildlife) with a party on the Sunshine Coast, when they came across some haggard and exhausted Stirling Castle survivors who had walked overland. Otter made haste to inform the Commandant of Moreton Bay, Foster Fyans, of the possibility of further survivors. Fyans sent Lt. Otter, two boats, a group of convict volunteers, and the pilot from Moreton Bay. Former convict runaway John Graham acted as diplomat and interpreter, and finally, rescuer.

‘The steward of the brig had walked over land to Moreton Bay, and there gave information of the situation of Mrs. F. and her unfortunate companions, when a man named Graham, who was well acquainted with the bush, volunteered to head a party, to the ship-wrecked people, and pledged himself to rescue them from the blacks. Lieutenant Otter and a party were immediately despatched, and with Graham, went in search of the unfortunate people. Mrs. Fraser states that Graham went into the midst of the natives, and at the risk of his life, snatched her up, and ran away to his party with her, and afterwards recovered the second officer in the same courageous manner.

Eliza Fraser was taken by boat to Brisbane Town and cared for by the wife of the Commissary Officer and the Assistant Surgeon. When she felt stronger, she gave a statement to Captain Fyans.

She didn’t mention David Bracewell.

Nor did any account until 1842.

By 1837, the presence of convict escapees in the Sunshine Coast area was becoming well known to Captain Fyans. The indigenous people of Bribie Island had reported the presence of William Saunders, James Ando, George Brown and Sheik Browne to him, and assisted in their capture. Lieutenant Otter and former runaway convict Samuel Derrington located David Bracewell the same month and returned to Moreton Bay with him on 23 May 1837. And there Bracewell remained until 21 July 1839. The reason Bracewell later gave to Russell for his final escape was a fear that the pending closure of the Moreton Bay penal settlement would see him transported to Norfolk Island for the rest of his sentence.

In May 1842, Andrew Petrie, Captain Joliffe and Henry Stuart Russell took a whaler north from Brisbane Town, to look for arable land in the Wide Bay area. They took with them two indigenous men as guides and interpreters. While Russell, a flamboyantly impractical explorer, was prostrated with sunstroke and being tended to by local aborigines, the party learned of a white man living amongst Eumundi’s people.

Petrie decided to write a note and gave it to one of his guides to give to the white fellow. That approach bore fruit, although the man could not read it, he knew it was from a fellow European. Russell described the man who approached his camp. “He was in looks an old man: his hard life had added its brand to the years of his seamed features. When washed and clothed, in a few days he became perfectly naturalised; had recovered much confidence and appeared to be really glad at having been rescued.”

Petrie and Russell had to persuade Bracewell that the convict colony had been packed up, and the place was open to free settlers. Bracewell then became part of the operation to retrieve James Davis, who had been with Pamby Pamby’s people for fourteen years.

Andrew Petrie, builder, architect and explorer who had been the Supervisor of Works at Brisbane Town, had travelled to Australia in 1831 on the Stirling Castle. He was interested in what had happened when the brig ran aground six years earlier.

David Bracewell became part of the Stirling Castle story with his discovery by Petrie and Russell’s party in May 1842. Having regained his command of English, he told his rescuers his tale of Eliza Fraser. Russell took the story to heart and related it in his 1888 memoirs. This is his version of Bracewell’s account of taking Eliza on the walk to Brisbane.

The odd thing about that story is that Mrs Fraser was taken to Brisbane by boat, with Lt. Otter and his party (including Graham).

During his time with Eumundi’s people and his two-year spell at Brisbane (1837-1839), no doubt Bracewell would have heard stories of the wreck, and the rescue of Eliza Fraser. That he did not report his involvement to his captors in 1837 is clear. No mention has been found of Bracewell giving his Stirling Castle story to anyone at Moreton Bay The record-keeping of the military men who oversaw Moreton Bay was thorough, down to how much everyone ate, how many cattle grazed and who refused their medicine.

It’s possible that the great talker was giving Petrie and Russell the story they wanted to hear. He didn’t tell the story to Dr Stephen Simpson, Commissioner of Crown Lands, who gave him employment and set about getting him a ticket of leave. At no point in any of Simpson’s correspondence about Bracewell does the Stirling Castle story appear.

David Bracewell (Wandi) and James Davis (Duramboi) returned to Brisbane Town on 22 May 1822 on Petrie’s boat. The two men were slightly stand-offish with each other at first, according to Russell. Tom Petrie recalled the two men sitting cross-legged (they called it “tailor-fashion”) and recounting their stories to the settlers in Brisbane.

In his 30 May 1842 report to the Colonial Secretary, Foster Fyans recounted the return of the two runaways, and advised that they had been attached to the Police in Brisbane. Fyans recommended that they be mounted and attached to the Border Police.

Dr Stephen Simpson employed David Bracewell as a bush constable, interpreter and splitter over the next two years. In January 1843, he and Davis took charge of Stephens’ dray during an excursion to Wide Bay. In March, he interpreted on a sojourn to Bunya Country, to look at the possibility of the German Mission being relocated there. Simpson decided that there were not enough aborigines settled there to minister to.

Bracewell contributed his favorable view of Fraser Island as a place for the Mission. He described for Simpson the indigenous population, the land and the abundance of resources. Simpson also felt that the island might “become an Asylum for aborigines when driven from their habitat”, as offhandedly callous a remark as ever an earnest 19th century “friend of the aborigines” ever made. The people of Fraser Island did suffer a great deal in the coming decades, at least partly as a result of the grim tales told by Mrs Fraser and her fellow survivors of the Stirling Castle.

Commissioner Simpson and the Colonial Secretary had another problem with the German Mission. The Rev. W Schmidt published his diaries of the journey to the Wide Bay area, and it contained a mention of the poisoning in 1841.

SOMETHING THAT MUST BE ENQUIRED INTO.

IN the Observer of Saturday last is the commencement of a journal kept by the Rev. W. SCHMIDT, one of the German Missionaries to the blacks in the Moreton Bay district, in which, speaking of the disinclination of some natives to accompany him in a particular direction, Mr. S. says, “There was also another reason which influenced greatly our natives against going any further, viz.-A LARGE NUMBER OF NATIVES, ABOUT FIFTY OR SIXTY, HAVING HEEN POISONED AT ONE OF THE SQUATTERS’ STATIONS.” From what we have heard of Mr. SCHMIDT, we believe him to be a prudent, cautious man, who would not make a statement conveying such a serious charge as that of murder against any one, unless he felt convinced that he had good authority for so doing. It will be perceived that there is no hesitation in Mr. SCHMIDT’S assertion; he does not allude to the charge as a rumour, or as dependent upon the testimony of the blacks themselves, but boldly and unconditionally asserts that fifty or sixty blacks had been poisoned at one of the squatters’ stations.

This grave charge cannot be allowed to pass unnoticed. It is the duty of the GOVERNOR, and the Law Officers of the Crown, to cause a charge thus publicly made by a respectable member of society to be enquired into : it is not like an anonymous communication in a newspaper, but purports to be, and we presume is, an extract from a diary or journal kept by Mr. SCHMIDT, a copy of which is doubt-less sent to Europe, and read by the friends of the mission there.

If so foul a murder has been committed, we trust the guilty parties will be found out, prosecuted, and meet with the punishment due to the perpetrators of so diabolical an act.

It becomes, therefore, the duty of every individual squatter in the direction of the Bunya Bunya country, to which Mr, SCHMIDT was travelling at the time, to take steps to relieve himself from the imputation under which they all labour: for the charge is so general, that it does not affix itself to any particular person ; but as there are very few stations in that neighbourhood, it will not be difficult for all who feel confident in their own innocence to unite in denying any knowledge of the transaction, and calling on Mr. SCHMIDT to state the particulars.

But under any circumstances, the charge must not be allowed to drop. IT MUST BE ENQUIRED INTO! Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842 – 1954), Monday 5 December 1842, page 2

There was a bureaucratic panic. Dr Simpson was directed to question Rev. Schmidt about the publication and report the response he received. Most particularly to check whether there might have been an error in the transcription of the diaries to the newspaper. For the next six months, correspondence and reports would be exchanged between Simpson, the Colonial Secretary, The Governor and the German Missionaries. The Germans felt that the matter should “not be lost sight of”, and the Government wanted to know what they meant by that. Bracewell was questioned and came up with the same information as James Davis. There had been a poisoning, and the murder of two white men weeks later was in retribution. The matter of the German Mission being relocated was quietly dropped.

Bracewell continued to work for Dr Simpson, as an interpreter and bush constable until on 28 March 1844, Wandi the great talker was killed by a falling tree at Dr Simpson’s property, Woogaroo. He was buried at the first free settlers’ cemetery at Skew Street (E.E. McCormick Place), Brisbane, along with the deceased officials of the colony, and Granville Stapylton, the murdered surveyor.

SOURCES:

Cox, Jane (November 2013). Old East Enders: A History of Tower Hamlets. The History Press.

Russell, Henry Stuart. The Genesis of Queensland, 1888, Turner and Henderson, Sydney.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online, September 1826, trial of DAVID BRACEWELL (t18260914-375).

The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842-1954), Tuesday 02 April 1844, page 3, “News from the Interior”.

Sydney Morning Herald (NSW: 1842 – 1954), Monday 5 December 1842, page 2

Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Qld: B00063, page 1459. Volume V1844104329.

Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828 – 1838), Friday 7 October 1836, page 3

McNiven, Ian. Ethnohistorical reconstructions of Aboriginal lifeways along the Cooloola coast, Southeast Queensland [online]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland, The, Vol. 102, 30 Aug 1992: 5-24.

Sydney Monitor (NSW: 1828 – 1838), Friday 7 October 1836, page 3

Guardian (Sydney, NSW: 1844), Saturday 6 April 1844, page 27 (2)

NEW SOUTH WALES – COLONIAL SECRETARY LETTERS RELATING TO MORETON BAY AND QUEENSLAND RECEIVED 1822 – 1860. LETTERS RECEIVED 1842 – 1843 AND PAPERS FILED WITH THEM

06.05.1843: 43/03944

10.03.1843: 43/03944

14.01.1843: 43/00624

19.06.1843: 43/00219

27.05.1843: 43/04579

27.04.1843: 43/03467

01.01.1844: 44/03049

01.10.1843: 44/03049

01.07.1843: 43/08025

01.04.1843: 43/05456

01.01.1843: 43/05456

NEW SOUTH WALES – COLONIAL SECRETARY. LETTERS RELATING TO MORETON BAY AND QUEENSLAND RECEIVED 1822 – 1860. LETTERS RECEIVED 1838 – 1839 AND PAPERS FILED WITH THEM

08.11.1836 36/09780

06.09.1836 35/08330

List of convict volunteers in the recovery of the Stirling Castle survivors:

- John Graham/ “Hooghley” – labourer, 2. Nathaniel Mitchell/ “Eliza” – ploughman, 3. John Walsh or Cartwright/ “Minerva” 4 – mariner, 4. John Williams/ “Marquis of Huntley” 1 – seaman, 5. Christmas Paulgrove/ “Guildford” 6 – labourer, 6. Thomas King Thompson/ “Nithsdale” – shoemaker, 7. John Phillips/ “Vittoria” – errand boy, 8. James Pretty/ “John” 1 – groom, 9. John Shannon/ “Champion” – butchers boy, 10. John Lindsay/ “Fairlie”, 11. John Daley/ “Sir Godfrey Webster” – weaver, 12. William Brown/ “Waterloo” 3 – waterman, 13. James King/ “Phoenix” 3 – dyer, 14. Thomas Kinsella/ “Cambridge” – pedlar.

NEW SOUTH WALES – COLONIAL SECRETARY. LETTERS RELATING TO MORETON BAY AND QUEENSLAND RECEIVED 1822 – 1860. LETTERS RECEIVED 1841 – 1842 AND PAPERS FILED WITH THEM.

30.05.1842: 42/04284

Drummond, Yolanda Brisbane, Qld. Royal Historical Society of Queensland, 1993 . Progress of Eliza Fraser Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland volume 15 issue 1: pp. 15-25

Ryan, J. S. (John Sprott) Brisbane, Qld. Royal Historical Society of Queensland, 1985 Captain Foster Fyans and Mrs. Eliza Fraser, Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland volume 12 issue 2: pp. 260-263

Queensland State Archives Agency ID2753, Commandant’s Office, Moreton Bay:

Queensland State Archives Series ID 5653, Chronological Register of Convicts at Moreton Bay

Queensland State Archives Series ID 5652, Book of Monthly Returns of Prisoners Maintained

Queensland State Archives Series ID 5645, Book of Public Labour Performed by Crown Prisoners (Spicer’s Diary)

Picture of Eliza Fraser: State Library of Queensland.

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..extra wait .. …

LikeLike