Judges and Magistrates still have faith in the human spirit. They look at certain defendants, and see something that makes them believe that a kindly intervention early on might just change the defendant’s life.

I’ve heard a Magistrate tell a weeping girl, terrified of her parents finding out about an offence, “They might be angry with you, but that’s because they love you.” The girl responded well to the fatherly approach, and never reoffended.

The Abominable Curse of Drink

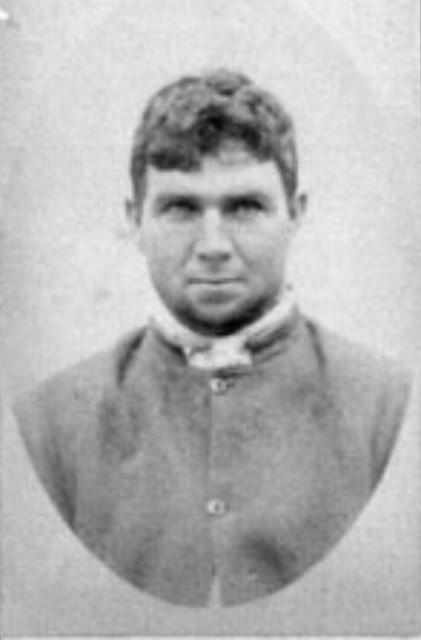

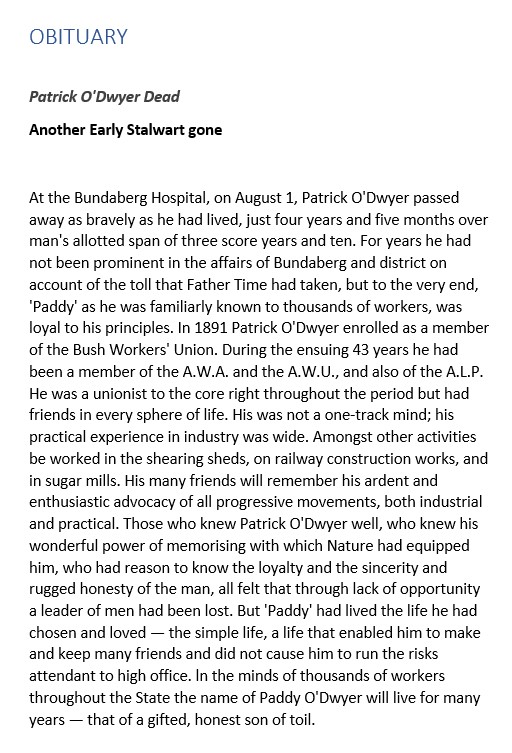

On 15 July 1890, the Police Magistrate at Maryborough, Mr G.M. Lukin, Esq., saw something hopeful in young Patrick O’Dwyer, before him on a charge of obscene language. If O’Dwyer could turn from the path of intemperance, the promise he showed could be realised. Magistrate Lukin remanded O’Dwyer to the following day in order to consider his sentencing options.

The P.M. told him that the language used was the filthiest and most horrible that could have been expressed by any man, black, white, or yellow. He could not understand how such a young strapping healthy fellow like the accused could throw his life away on the abominable curse of drink. He was richer than nine-tenths of the inhabitants of Maryborough on account of his splendid physical attainments.

Maryborough Chronicle and Wide Bay Advertiser.

Patrick O’Dwyer had been released from custody the previous morning, having served his third short custodial sentence, courtesy of the Bundaberg Bench. Magistrate Lukin thought it over. He would admonish O’Dwyer, and release him on a good behaviour bond. He urged Patrick to consider taking the pledge – if only just for a year. However, if O’Dwyer didn’t behave well, he would be called up for sentencing.

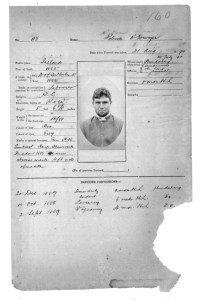

And so it was that a month later, Patrick O’Dwyer and his splendid physical attainments stood before the photographer at Brisbane Gaol. O’Dwyer was convicted of obscene language, assault and vagrancy at Bundaberg less than two weeks after Magistrate Lukin lost sleep over his future.

For being such a sore disappointment to everyone concerned, O’Dwyer went in for 8 months’ hard labour.

Perhaps the promise that Lukin had detected would be shown in some other aspect of his life.

A Stalwart Labour Man

Patrick O’Dwyer was born in Fethard, Tipperary, in 1866 to John and Eliza O’Dwyer. On 30 March 1885, he arrived in Brisbane aboard the immigrant vessel Duke of Sutherland, and set out to find work as a labourer. Young Patrick wasn’t afraid of hard work, but he liked to drink hard too. When he drank, he became aggressive, used obscene language and sometimes committed minor property offences.

O’Dwyer became a well-known figure in Bundaberg over the years, but not just because of his physique and drunken exploits. In 1891, he joined the Bush Workers’ Union, and showed leadership through decades of activism for the Australian Workers’ Union and the newly formed Australian Labour Party.

His friends in the labour movement always assumed that Paddy was too modest and humble to seek high office in either the Unions or in politics. But I suspect that his long, alcohol-stained criminal record put paid to any ambitions for public life.

Throughout the 1890s, Patrick O’Dwyer worked about the Bundaberg and Maryborough area, racking up disorderly behaviour and obscene language charges on his days off. On one occasion, he lost his temper in the watch-house and wrecked the cell bucket (property of the Queensland Government) for good measure. Hopefully the bucket was empty when O’Dwyer took out his frustrations on it.

Just before Christmas 1898, Patrick O’Dwyer married Elizabeth Nixon, and settled down considerably. They started a family, and it was not until 1909 that Paddy faced another serious charge. Alcohol was involved, and he had no memory of the offence afterwards.

Waking up with a Strange Doll

Patrick had been drinking in the Hotel de Posen at South Kolan, and woke up the next morning with no idea where he’d been. He found himself in possession of lace scarf, comforter, and a doll. O’Dwyer thought he would be an upstanding citizen, and went to the police to advise that he’d found some lost property that might belong to a girl who’d cleared out of the hotel the day before. The Police thanked him, told him that there was no missing property report, and sent him back to his quarters. They tried not to laugh out loud when a doll fell out of Paddy’s great-coat.

Then a young girl by the name of Wills, who worked at the Hotel de Posen, complained to her boss that she had woken in her room to a man loitering outside the window. She went off to sleep in another part of the hotel for safety, and in the morning discovered that the window had been forced open, and her property had been rifled about. She was missing some clothing and a doll. Her boss told the Police, who knew just who to see about the doll and lacy scarf.

Patrick O’Dwyer was identified as the face at the window, and the doll was produced to the Court amid much laughter. The defence relied heavily on the level of intoxication and forgetfulness, and the jury eventually found Paddy not guilty.

In discharging the prisoner His Honour said he might consider himself a very fortunate man. Should he continue to misbehave himself in the future he might meet with a jury that would not take so lenient a view of his case. The prisoner on leaving the dock returned his thanks to His Honour.

Bundaberg Mail

In 1911, Patrick O’Dwyer was charged with assaulting a teenaged girl, who was arriving home one evening after a trip to the pictures. The girl contended that O’Dwyer rode up behind her, claimed to be acting on the direction of the police, and told her that she was in trouble for staying out late. He then grabbed her by the wrists and pulled her away from her gate.

Fortunately her father heard the horse’s hooves, and went outside to see what was happening. Confronted, O’Dwyer apologised, let the girl go and rode off.

O’Dwyer’s defence was that he was drinking heavily and had mistaken the girl for a woman he knew (who had taken some of his money to buy drinks and had vanished with it). He was lucky to leave court with just a hefty fine, as the Bench and the girl’s father contemplated what might have happened that night had O’Dwyer not been interrupted.

I have a number of convictions for various offences. I don’t know whether there are forty-two of them. I have not been convicted of assault since I was married.

Patrick O’Dwyer, 1911 court hearing

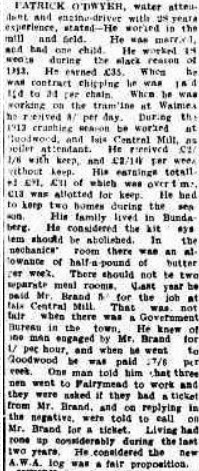

Once again, Patrick O’Dwyer went home from Court a free man, and tried to lead a more responsible life. He gave evidence to a special sitting of the Industrial Court at Bundaberg – his knowledge of the pay and conditions of his fellow labourers was invaluable.

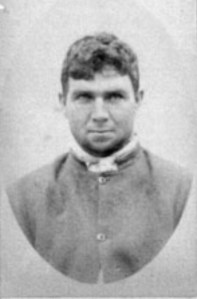

Paddy was also the subject of a letter to the editor of the Brisbane Courier in January 1916. He was a “robust and well set-up man” who tried to enlist in the armed forces, and was refused by one doctor for rheumatism, cleared by another, and generally put to a lot of trouble, cost and frustration in his desire to serve his country.

Too Old, Too Drunk.

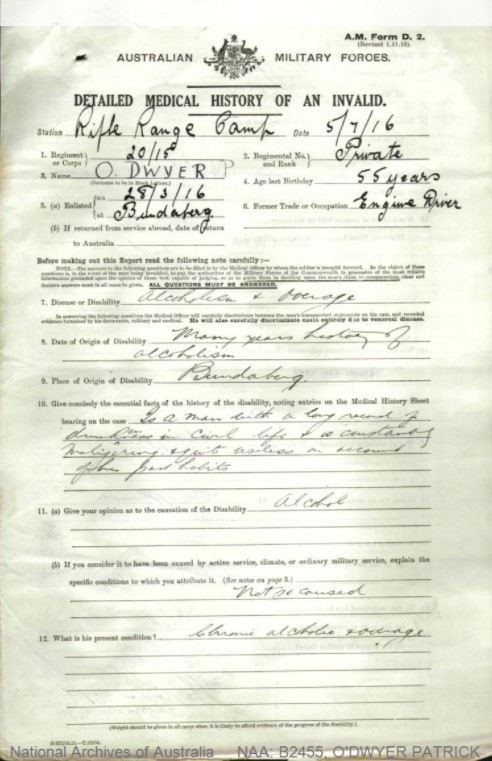

The Australian Imperial Forces relented, and Patrick O’Dwyer was allowed to sign up in March 1916 at Bundaberg. His intentions were good, but the A.I.F. didn’t take long to realise the problem at hand:

Paddy’s alcoholism did not end with the cutting assessment from the Australian Military Forces. He spent less time in the lock-up for obscene language and drunkenness, but that was because his drinking was done at home now, at the expense of his wife of a quarter of a century, Elizabeth.

The Police Magistrate, Mr C.D. O’Brien, delivered a lecturette on the contemptible nature of the defendant’s action, particularly as the assault was alleged to have been committed with a knife, stating that in future it would be well for O’Dwyer to remember that people of the British race do not resort to the use of knives, except in cases when the odds are such as to justify the use of any weapon procurable. “When, called upon to do so,” said the P.M., “use your fists, but against a woman – use nothing.”

Bundaberg Mail, 7 October 1924.

A similar incident occurred the following year. Patrick O’Dwyer was in his sixties, and a lifetime of hard work and harder drinking was catching up to him. His last years were quiet, and he passed away on 1 August, 1934.

Patrick O’Dwyer Charge Sheet 1890

Detail from Charge Sheet

Bundaberg Court 1889

Bundaberg Police Station, 1902

Employer Bingera Sugar Mill 1902

Bundaberg 8 Hour Day March 1910

Enlistment Application 1916

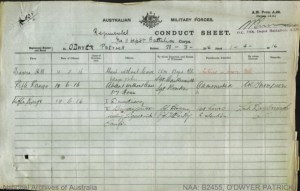

Regimental Conduct Sheet, 1916

Bundaberg Hospital