1850 – 1860: The answer to our economic prayers.

In 1850, Moreton Bay looked forward to the arrival of 108 Chinese labourers, brought in by the ship, Favourite. All had been indentured to employers prior to landing, and competition for their services had been fierce. More Chinese workers were promised. We could hardly wait. They would save our economy in a time of labour shortage. The Chinese were skilled and capable, they made excellent shepherds. They weren’t convicts or convict exiles. They were quite cheap to employ. A few people here and there complained that the “starving and guiltless poor” of the United Kingdom would be preferred as nation-building labourers, but nobody minded too greatly.

Occasionally, a Chinese labourer would run foul of our (English) laws and habits, but overall, we were grateful for the assistance Chinese workers rendered in setting up our agriculture and economy. It was a fairly controlled form of labouring immigration, and the attitude expressed by the Moreton Bay Courier could not have been more conscientious and understanding.

His (the Chinese worker’s) lot is cast amongst a population but little disposed, in the mass, to sympathise with his misfortunes or to appreciate his regrets; and he has further to contend against the undisguised and bitter hostility of the labourers of our own country, who look upon him as an interloper, and as an instrument in the hands of others to bring down the rate of wages and reduce themselves to a condition but little better than his own.

As subjects of a nation at present at peace with Great Britain, those Chinamen have a right to the protection of our laws; but taking into consideration the vast dissimilarity between those laws and the customs of the country from which they come, it would appear to be a binding moral duty in our own people, to see that the laws and customs which we enjoy, and in the enjoyment of which they are invited to participate, are made known to them, and placed within their reach.

Moreton Bay Courier, February 22, 1851

Distant Gold

In 1851, Victoria was found to have gold deposits approaching those in California, and a rush commenced. Tent cities appeared, and it was every man for himself. By 1854, the colony of Victoria was host to a lot of Chinese diggers, as well as Europeans, English and Australian-born miners. There were vast tent cities appearing within days of a strike, and competition for the best spots for digging was fierce to the point of being deadly.

It’s hard to imagine such a situation occurring today, as large resource companies tender for exploration licenses and leases in remote parts of the country. Any excitement felt is limited to the stock-exchange, and in the pockets of fly in-fly out workers.

Violence broke out between Chinese and European miners, and Queensland newspapers reported, with no small degree of horror, on the injustices visited on Chinese miners at the diggings in Victoria.

The unfortunate Chinese are doomed to ill-treatment from all quarters. Today our police report contains an account of six of them being put in durance vile for having in their possession gold while attempting to place the Murray between them and the Buckland.

Moreton Bay Courier, 08 August 1857.

After all, it wasn’t happening here. We had, to our knowledge, no resources of value that could become the subject of a rush, European or otherwise. We could afford to be civil. Until it no longer suited us.

1860-1870: Gold in the North

By the 186os, gold, although not on a par with the richness of the California or Victoria fields, was being found in Queensland. The payable alluvial gold discovered by Nash at Gympie in 1867 was credited with saving Queensland’s economy. At Gympie, there appears to have been little of the squabbling that would erupt in the northern goldfields, and the majority of mentions of the Chinese in newspapers of the time relate to agriculture.

Hot, remote places above the Tropic of Capricorn, like Crocodile Creek and the Palmer River Goldfields began to attract European and Chinese miners alike. By 1866, there were fears that unrest could occur, due to the number of Chinese miners arriving at the diggings:

The following year there was what was called a “roll-up” against the Chinese at Boulder Town. By “roll-up” I believe the reports meant race riot and destruction of property with no injuries or loss of life.

We have no proof as yet of the guilt of the men apprehended, but abundant evidence that the “roll-up” was a cowardly attack by a number of European blackguards upon an unoffending people, whose conduct contrasted favourably with that of their persecutors; and that, with some honourable exceptions, the Europeans attracted to the scene of disturbance stood by as passive spectators.

The Queenslander, 19 January 1867.

Before 1870, the phrase “The Chinese Question” was mainly used to refer to ongoing struggles in New South Wales and Victoria.

1870-1880: The Chinese Question emerges.

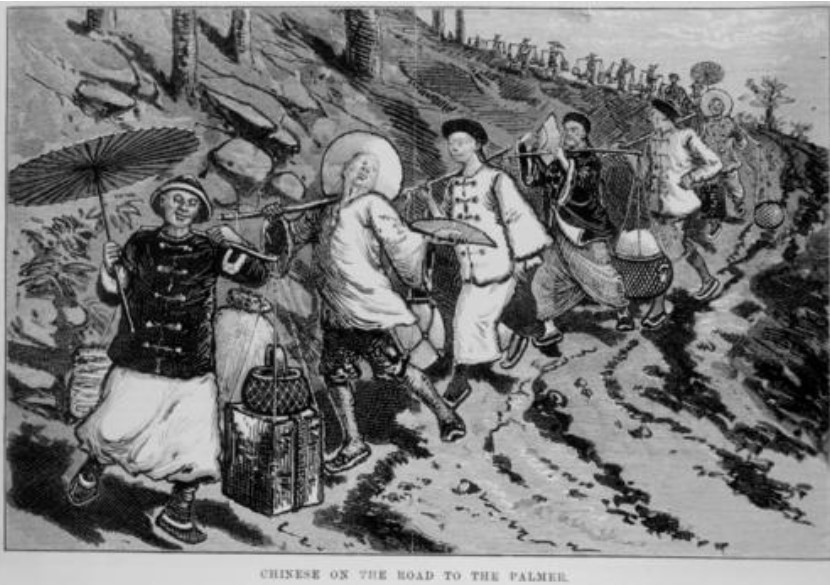

The 1873 drawing “Chinese on the road to the Palmer” was presumably made to point out the foreignness of the Chinese by their dress and attitude, and the number of them heading to the Palmer River Goldfields by the line of figures trailing off into the distance. To a modern observer, it’s a fascinating look at the clothes, footwear, stockings and hats worn by those long-ago fossickers.

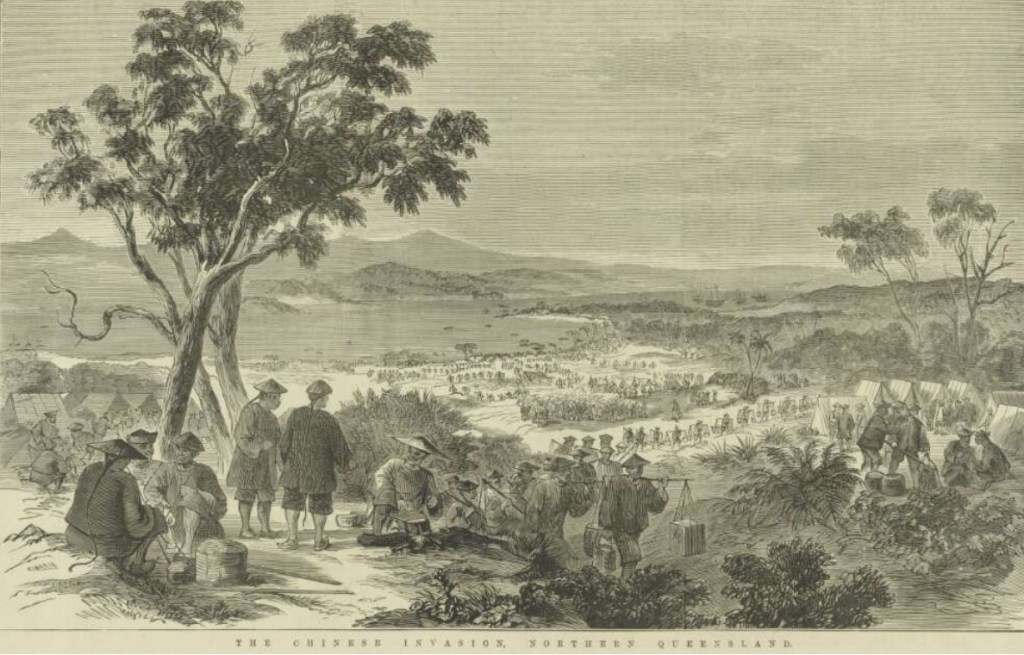

Three years later, “The Chinese invasion of Northern Queensland” depicts a never-ending line of Chinese men, stretching all the way to the distant horizon, all the figures are identically dressed, each with a pigtail and coolie hat. The individuality of the Chinese drawn on their way to the Palmer Goldfield is gone. Everyone is identical. And we’re meant to see that as a threat.

In the early 1870s, reporting on the Chinese in Queensland involved the usual mocking reports of misunderstandings in Courts, such as “What religion are you?” “Lockhampton”. No which church do you go to?” “Roman candle.”

The phrase “The Chinese Question” appears from 1870 onwards – sparingly at first, then by 1876, it is used on an almost daily basis. It seems to have been a portmanteau term for everything from “reasonable concern at lack of taxes paid by foreign workers” to “that’s probably too many immigrant workers coming in at once” to outright racism.

What was the Question?

What were the concerns? A long survey of the sources reveals that the Chinese Question could be divided into four issues.

Foreigners taking Australia’s wealth away from Australians. (This is a concept that must have elicited some quiet head-shakes from indigenous Australians). It was estimated that at one point during the various rushes, there were 50,000 Chinese people in Australia for work. European Australians found the non-citizenship of the Chinese particularly difficult to understand. In the view of the time, non-citizens who had no land ownership rights should not be permitted to dig the land, and take the mineral wealth back to their foreign country with no taxes or duties paid to Australia. Various Colonial Governments then set about imposing levies, to the indignation of the Chinese.

Foreigners who don’t want to contribute the the Colonies: The social variant on the above argument. It was claimed that the Chinese diggers did not, as a rule, bring their wives and children to Australia. The Chinese were, it was claimed, only here to build up a pile of money to take home to China. In the same vein: English was not learned, Christianity was not practiced, assimilation did not take place. The view was stated that having an estimated 50,000 people who decline to be naturalised was undesirable in such a lightly-populated Colony.

Disease and vice: “They introduce among us a loathsome and incurable disease and nameless vices; and neither the healthfulness nor the morality of Queensland stands so high that we can afford to regard with indifference anything that lowers them.” I have no idea what this means. A lot of reading has pointed me in the general direction of a view that the author of the article I’m quoting may have meant leprosy? Because the English brought venereal disease here. The nameless vices remained nameless, unless the author meant opium and gambling. And European Australians were loathe to drink or bet.

There are just so many of them: The following phrases are from one short article from 1878. “swamped by hordes of Chinamen,” “the possible inundation of the colony with Chinese,” “the teeming millions of China,” “Already there are no fewer than 11,000 Chinese on the Palmer diggings, and only about 2500 Europeans,” and, lastly, “check this undesirable influx.”

The 1880s: Build-up to a Riot.

The Chinese Question was being asked every day by 1880, and the Colony’s politicians were quick to notice. Whether Mr and Mrs Average Queensland was affected by Chinese migration, or understood or even asked the dreaded Question, was immaterial. By hearing the phrase the Chinese Question mentioned endlessly in newspapers and in political speeches, Mr and Mrs Average Queensland were sure to come to the view that whatever it was, something must be done about it.

By the 1880s, there were Chinese people in towns and cities throughout Queensland, people who were putting down roots in business and the community. The Chinese Question, which may have been born of the presence of strangers at the gold diggings, took on a different character when the urban Chinese were considered.

Market Gardens run by Brisbane’s Cantonese community supplied all of Brisbane’s fresh fruit and vegetables, and successful Chinese businesses were established in Albert Street in the City and in Fortitude Valley.

This photo detail shows Yuen King Kee & Co, merchants (with Holloway’s advertisement on the side). Further up the right side of Albert Street were Nam Yoe, (Storekeeper) at 54 Albert St, Sam Lee’s Chinese Fancy Goods Shop at 68 Albert Street, and Sun Yen Chong, (Storekeeper) at 70 Albert Street.

In 1886, the building referred to at the time as the Breakfast Creek Joss House – the Holy Triad Temple – was opened. It had been constructed by the representatives of five Cantonese clans living in Brisbane at the time, and became a cultural focal point for the Chinese community. The Temple still stands, and still provides that focus. It has been added to the Queensland Register of Historical Places, and is located at 32 Higgs Street, Albion.

A building in Frog’s Hollow called the Nine Holes attracted a lot of fear and loathing, principally from journalists. It first came to media attention in the early 1880s, as a place where opium was smoked, and rather a lot of fan tan was played. It was said to be in a filthy condition. An official inspection of the buildings led to some unsanitary drains being fixed – reluctantly – by the very hands-off (European) owner. As the decade progressed, the Nine Holes became associated with some (European) prostitutes, who came for the shelter and stayed for the opium. The Police Magistrate, Mr Archdall, made it his mission to cleanse the town of the Nine Holes, but it took the 1893 flood, with all of the building damage and property loss, to move its residents on.

The Figaro, the 1888 election and a riot.

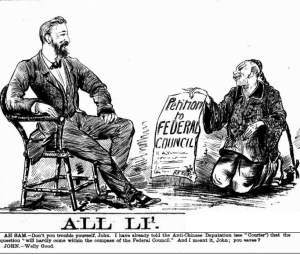

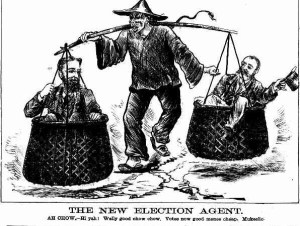

That decade also saw a new weekly newspaper published. It was The Queensland Figaro (1883-1885), which became The Queensland Figaro and Punch (1885-1936). The first editor was John Edgar “Bobby” Byrne, and to say that Mr Byrne did not welcome Chinese immigration is an understatement. In 1888, the Figaro was spoiling for a fight with Sir Samuel Griffith about his perceived support for Chinese interests.

Here’s how Figaro chose to illustrate its point:

There was an election due in mid-1888, and broadly put – Sir Thomas McIlwraith campaigned on an anti-Chinese platform and Sir Samuel Griffith, well, did not. (It is hard to know exactly how Sir Samuel Griffith felt about such issues on principle – given his wildly changing stance on South Sea Islander slave labour. He may not have been motivated by anything beyond political self-interest.)

The riot occurred on the day that the electorate of Stanley (which contained Brisbane City) was deciding its candidate. The result was called around 9 pm. McIlwraith won, and was nearly overcome by his supporters. One street away, the riot started in the Albert Street Chinese business precinct. The following Monday, the Brisbane Courier wrote: “The real cause of the demonstration is hard to tell, but it is generally believed to have been at least encouraged by persons whose social position should have placed them above such behaviour.”

I presume they meant McIlwraith and Griffith. Surely the editors and journalists who wrote the fusillade of “Chinese Question” articles weren’t a causal factor? Never.

In the aftermath of the Brisbane riot, the Chinese Question (whatever it was) was not raised as frequently by the press. Not that this heralded a new era of reasoned immigration debate – given time, the Chinese Question became the Kanaka Question, which merged with the Chinese Question to become the Coloured Labour Question, which became the White Australia Policy. But the Chinese people of Brisbane no longer faced thousands of people descending on their homes and businesses with bricks and stones.

Not as fond of recording every aspect of their lives as their European brethren, the Chinese experience in early Queensland has not been extensively recorded on film, but here are a few glimpses from the archives.