Being Governor of the Colony of Queensland was not an easy task. The Colony separated from New South Wales in 1859, with the arrival of Sir George and Lady Bowen, transitioning to a State in 1901 with Lord and Lady Lamington.

In between those dates, the men and women of the first families were tested by their duties in a number of ways, including, but not limited to –

- Dealing with a rabble of squabbling politicians unaccustomed to high office, and unwilling to compromise in any manner. Worse, much worse, than today. Truly. We kept proroguing the parliament.

- Dealing with the climate, which came as rather a surprise to those of the English persuasion (and those of the Greek persuasion, if Lady Bowen’s sufferings are anything to go by).

- Exhausting travel about the vast Colony by steamer, rattling early railroads and by carriage. Such pilgrimages took weeks rather than days.

- Sadly, one did not always survive the appointment.

Then there were particular challenges faced by each Vice-Regal family.

Sir George Ferguson Bowen GCMG*

1859 – 1868

*Knight Grand Cross (of the Most Distinguished Order) of Saint Michael and Saint George. Also translates as: “God Calls Me God.”

Sir George and Lady Bowen had the unenviable task of trail-blazing the job of Governor and first lady. When they arrived, there was no Government House, no Parliament House and they were faced with some truly awful verses celebrating their arrival.

The glamorous, aristocratic couple wowed the Colony, but had a few odd moments on the way. There was a nasty incident early on, as the Governor went out riding with the Colonial Secretary, shots were heard, and very nearly felt. The Colonial Secretary’s beaver (hat) narrowly missed being punctured by a bullet. No assassins lurked in the sub-tropical undergrowth, it turned out that a couple of boys were larking about with a gun (as one does), and happened to discharge it near the two most important people for a thousand miles.

Poor Lady Bowen underwent subtropical confinements, crinolines and dreadful poetry. She was shaken, but not stirred, by a travel mishap on the crude line of road from Sandgate.

Then Sir George had the misfortune to come to the attention of one James Alpin McPherson, alias The Wild Scotchman. No, he wasn’t threatened or bailed up, but the cheeky bushranger felt it was only right to complain to the Governor about the sorry state of the mails. Some were hardly worth sticking up.

Queensland did its best to compensate for these lapses in protocol by naming everything they could after the Bowens. When Sir George and Lady Bowen left after eight years, her Ladyship wept freely, apparently not from relief.

Colonel Samuel Wensley Blackall

1868-1871

Colonel Samuel Blackall had a hard act to follow. The dynamic double act that was the Bowens left Brisbane after eight years, and Colonel Blackall was twice widowed and in less than robust health. He had a long and distinguished military, political and foreign service career behind him, but passed away in office two years after arriving. His term was marked by even more furious political squabbling, something that doubtless hastened his decline. The staff of Government House did their best to care for the old gentleman, who dedicated the new Toowong Cemetery with a heavy heart, having already selected a hilltop spot for his long repose in the Queensland sun.

The Most Honourable George Augustus Constantine Phipps, Marquess of Normanby GCB GCMG PC*

1871 – 1874

*Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath. Knight Grand Cross (of the Most Distinguished Order) of Saint Michael and Saint George. Privy Council.

The article announcing Normanby’s appointment shows us exactly where we are in time: SPECIAL TELEGRAMS.

The Marquis of Normanby has been appointed Governor of Queensland. Paris surrendered through starvation. The Prussian troops marched through the city and large supplies of provisions followed. An Armistice was granted to arrange the terms of peace.

George Phipps, despite his aristocratic background, saw himself as a public servant first and foremost. Okay, not exactly most the humble servant, but the sort that would nevertheless work hard and amiably with the governments under his command.

Normanby and Laura, the Marchioness, had the good fortune to arrive in Queensland during a relatively sane period in its political history, and his time as Governor was spent connecting with the people of the Colony, rather than trying to put out ministerial fires.

Like Lady Bowen before him, Normanby was the target of crappy Colonial poets. There ought to be a law against this sort of thing. The Normanbys saw themselves out in 1874 when Sir George took up the Governorship of Victoria.

Sir William Wellington Cairns, KCMG*.

1873 – 1877

*Knight Commander of the Order of Saint Michael and Saint George. Also: “Kindly Call Me God.”

Sir William Cairns, like the Bowen family, had a lot of things named after him. Including the city of Cairns, which is pronounced Cairns, not Cans.

It’s a cruel irony that a city in the sweltering tropical far north of the State should be named after a Governor who felt that his health had been destroyed by living and working in the tropics, and whose tenure in Queensland was cut short as a result.

It is also odd, given his frail health, that his is the most dynamic photograph of a 19th century Queensland Governor. It is partly due to the photo being a close-up in the age of “get the feet in,” and partly due to his wearing a suit and tie, rather than the quasi-Georgian fancy dress that other Governors adopted when being captured by that camera contraption.

Perhaps due to his introverted nature, Cairns travelled little during his tenure, intervened little in the process of government, and made few friends in the Colony. He also did not have a family to participate in the life of the Colony.

However, for all his failure to please the local grandees and the press, he did have a strong view of injustice. Referring to the controversial treatment of indigenous Australians by the Native Police, Cairns instructed his Colonial Secretary that, ‘inhumanity should never be resorted to, or palliated or left unpunished’. After his foreign service, Cairns had hoped to be an advocate in parliament for the people of the distant lands he had served in, but his health again failed him.

Sir Arthur Edward Kennedy GCMG CB*

1877-1883

*Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath. Knight Grand Cross (of the Most Distinguished Order) of Saint Michael and Saint George. “God Calls Me God.”

This famous photograph was taken of Queensland Governor Sir Arthur Kennedy during a Royal Tour of the Colonies, and is labelled “Visit of the Detached Squadron with their Royal Highnesses Prince Edward and Prince George of Wales to Brisbane, from 16th to 20th August, 1881.” Having thoroughly bamboozled myself with imperial honours and their attendant initials, I have not been brave enough to research what a detached squadron might be composed of. The Royals in question are, according to the information with the photo, standing at the centre of the photo in white double-breasted suits. (Although the fellow at the rear far left looks rather like Edward VII to my untrained eye.) Oh, and in this picture, they’re standing under the Traveller’s Tree, which I had the temerity to trim photographically, because I was anxious to see the people in the photograph, not some confection of outsize tropical foliage.

Queensland was the final posting in Sir Arthur Kennedy’s long foreign service career. The recently-widowed Kennedy was considerably older than his predecessor Cairns, but a little more robust. He was also able to cope in the tropics, having just completed a term in Hong Kong, and his daughter Georgina looked after the first lady duties during his term.

Sir Arthur, like Normanby before him, enjoyed a relatively calm relationship with the Colony’s government, and was able to put his experience and compassion to good use.

Eventually, Sir Arthur began to suffer from asthma, and sought to retire home to England in 1883. He was farewelled with great affection as he sailed for home, but sadly passed away as his ship reached the port of Aden. He was buried at sea.

Sir Anthony Musgrave GCMG*

1883-1888

*Knight Grand Cross (of the Most Distinguished Order) of Saint Michael and Saint George. “God Calls Me God.”

Sir Anthony Musgrave had a globe-trotting foreign service career, like several of his predecessors. Queensland, no longer requiring as firm a vice-regal hand as before, had become a fairly quiet final posting for a lot of career administrators. Musgrave, who had been born in the West Indies to a slave-owning family, had remarkably progressive (for the time) ideas on the indigenous people and was keen on the idea of federation.

However, this quiet late-career posting became troubled in 1888 when Sir Thomas McIlwraith was elected premier on a ticket of standing for just about everything Sir Anthony despised, not least of which was blatant racism. They clashed, and the premier won the first round. Sir Anthony delayed his retirement, fearing abuses of power, but died at his desk on 09 October 1888, either of strangulation of the bowel or angina pectoris, depending on which source you consult. Either sounds terrible.

Sir Anthony Musgrave is buried on the hill at Toowong Cemetery, near Governor Blackall’s grave.

Sir Henry Wylie Norman GCB GCMG CIE*

1889-1895

*Knight Grand Cross of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath. Knight Grand Cross (of the Most Distinguished Order) of Saint Michael and Saint George, Companion of the Indian Empire.

He had an adventurous military career, skirmishing heroically in India, followed by foreign service in Jamaica, ending up in (you guessed it) Queensland. Sir Henry Wylie Norman had a rather mournful air in photographs that belied his acuity of judgement and good humour.

Sir Henry bustled about the place, attending to the progress of Federation (although he doubted that we could all cohere as a nation) and promoting the interests of his subjects. He was a more popular figure than Sir Anthony Musgrave, probably due to the vitality of his temperament.

Having, he felt, knocked the place into shape, Sir Henry left for London, where he led a commission of enquiry, and as the new century dawned, became director of the Royal Chelsea Hospital. He passed away in 1904.

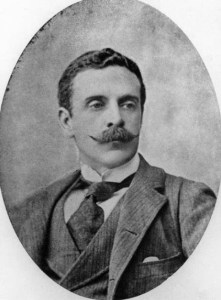

Rt. The Honourable Charles Wallace Alexander Napier Cochrane Baillie, Lord Lamington GCMG*

1896-1901

*Knight Grand Cross (of the Most Distinguished Order) of Saint Michael and Saint George. “God Calls Me God.”

Good God, that’s a lot of names. Quite a young man when he was appointed, he had already served in the British House of Commons, succeeded to his title and married before arriving here (via a bit of diplomatic derring-do in the Orient).

Politically conservative, he clashed at times with Sir Samuel Griffith, but the two men came to agree on constitutional and legal matters. Lamington followed Sir Henry Norman’s practice of visiting his constituents far and wide, and played a crucial role in the introduction Federation in 1901. He returned to England after his Queensland tour, and lived to a ripe and distinguished old age.

The Lamingtons were photographed more often than previous vice-regal families – understandably, they were living in the photographic era, and were younger and more active than their predecessors.

Here are my two favourite Lamington stories:

Defending the honour of a dentist’s wife, whilst travelling on a bicycle.

“A story leaked out today of a gallant rescue by Lord Lamington (the Governor) of a lady who had been assailed by two ruffians. His Excellency last Saturday returned from the Wellington Point Show (a distance of about fourteen miles) on his bicycle. On the old Cleveland road he saw a European and a Chinaman on horseback trying to gallop down a lady, also on horseback. The Governor rode in between, despite the insults of the two men, and escorted the lady safely into town. The lady is the wife of a well-known dentist.”

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld: 1860 – 1947), Wednesday 28 July 1897, page 2

Lamingtons: “Those bloody poofy woolly biscuits.”

These snacks – sponge cake dipped in chocolate sauce and rolled in desiccated coconut – were named after His Lordship. They may have been an accident in the kitchen, or a bit of improvisation by a canny cook with an empty larder, but they became associated with him. What he thought of them is recorded above. (These bloody poofy woolly biscuits may also be from New Zealand, a claim that I cannot investigate because I over-investigated the titles of these men, and am as a result suffering from Fancy Imperial Gong Fatigue.)

“Just take the bally photograph, you tedious little man.”