Tales from Early Queensland

The first European inhabitants of Queensland consisted wholly of those who had no choice in their destination. They were the convicts, soldiers and officials who made up the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement.

Upon its demise in 1842, very few remained to take part in the opening-up to free settlement. The Colonial government, headquartered firmly in Sydney, more than 500 miles away by sea, did little to set up this outpost.

As free settlers gradually moved in, the convict buildings were crumbling, land sales were scarce, and infrastructure was added only when a crisis proved the need for it. To make life even harder, Moreton Bay and beyond suffered a labour crisis, something that Lang’s welcome immigrants and the rather less welcome convict exiles in the late 1840s took care of.

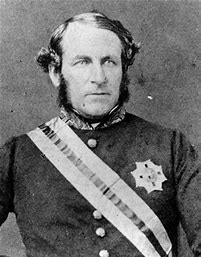

In 1859, Queensland became a separate colony in 1859, and, as our first Governor George Bowen confided, “As to money wherewith to carry on the means of Government, I started with just 7 ½ d in the Treasury.”[i] Some nights later, a thief broke in, and stole the money, forcing Bowen to borrow money from the banks to run the place until the revenue was collected.

Gold discoveries saved our collective bacon for a while, but the economy struggled along for most of the 19th century. In 1866, there was a shortage of work for the labourers, and in the 1890s, a cataclysmic depression saw the birth of the Labour movement.

For those who did not profit from the various mini-booms, life was tough. For the very poor, it was a struggle to survive. Poverty, illness, addiction and death tore apart struggling families. Children bore the brunt of it, going out to work to support their families instead of enjoying their childhood, or attending school.

Children of the Poor

Between 1870 and 1880, 175 boys between the ages of 6 and 19 were admitted to the Hulk Proserpine at Lytton on the Brisbane River. Of their occupations, 6 were orphanage inmates, 29 were schoolchildren, and 7 were working on farms. There are a couple of startling entries – two were “employed in a brothel,” (which on investigation turned out to mean that their mothers ran said brothels, and they were employed in housework), and one precocious 14-year-old was a barman. 99 of the children admitted were charged as being neglected and were sent to the Reformatory to learn a trade.

The Superintendent of the Proserpine, sometimes faced with children as young as 4, arranged for the very little ones to be given a sentence remission, and if their parents were not available, they were quietly sent to an orphanage to be cared for, rather than employ them in instructive physical labour. Most of the boys were licensed out to work for people as diverse as Sir Samuel Griffith, western graziers and the captain of a far northern schooner. Only those who were unable to work or completely obstreperous remained without employment.

Their stories are harrowing – usually involving death or desertion by one or both parents, or a parent going to gaol. 53 children found themselves without one or both parents. The surviving parent may lack the resources or the will to look after children after suffering the loss of a spouse.

Reformatory Boys.

If a boy was a burden to his parents, or broke the law, the opportunity of having him fed, housed and put up with by others seemed appealing. Particularly if the parent did not seem to care much for the children.

In our last issue we omitted accidentally to refer to an exhibition of parental feeling which, fortunately, is of rare occurrence even in our Police Courts. Three fine little fellows aged respectively three, five, and seven, appeared in the dock charged with stealing a piece of calico, the property of a person who had been on terms of friendship and intimacy with their father. The children had lost, or perhaps what is worse, had been deserted by their mother, and the father now appeared anxious to have them transferred to the Industrial School, which, considering the circumstances, his employment, and necessary absence from home, was the best thing that could possibly have happened to them. The children were accordingly sentenced to seven years in the ‘School,’ which sentence appeared only to be understood by the elder of the three, as from him alone were any exhibitions of grief elicited. Leaving the Courthouse, the children were escorted to the gaol by the police, the father refraining, even when requested by onlookers, from giving them a parting blessing, a word of love, or a last goodbye. In fact, they left the Court without even a sign or look that could be worthily treasured in remembrance of ‘home and father.’[i]

William Lafield and his wife applied to the Bench to have their son, Alexander, committed to the Industrial School, Brisbane. The boy was a young child, said to be eight years old, but very small and weakly for his age.

The Police Magistrate said he would send the boy for three years to the Reformatory School, and the parents must go and obtain their sureties. Mrs Lafield proposed to take the boy away and return with him, but on being told that he must remain in custody she placed him on a chair in the Court, and the little fellow burst into tears. The Lafields having left the Court, the child was removed in custody, His Worship telling the sergeant to put him in a separate cell.[ii]

Reformatory Girls.

If anything, it was worse for girl children. A Reformatory for Girls was opened in Toowoomba, and quickly filled with destitute girls who were sent to work in the laundry or kitchen, then, if their behaviour was not deemed totally unacceptable, licensed out to local worthies as skivvies. They could cook and clean, but no trade or profession awaited them.

Mr Wassal, the Superintendent of the Boys’ Reformatory, had the boys hired out far and wide, rating their behaviour on a scale from “indifferent” (rarely) to “Excellent”. “Very good” was the favoured report on Proserpine boys. Wassall believed in the license program and its potential to create good futures for his charges.

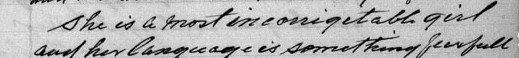

Mr Blaney, the Superintendent of the Girls’ Reformatory, by contrast, disapproved mightily of the girls in his charge. “Foolish, always laughing,” “wild,’ “incorrigible,” “unmanageable,” “defiant,” “sullen, stubborn,” and, most frequently, “flighty”.

And being girls, they were subjected to a lot of exploitation that their brothers were not. Most of the girls who arrived at the Reformatory – and who were vastly underage –had already been mistreated by boarders, family friends and sometimes their own fathers. In some cases, such as Elizabeth Shields’, their mothers sent them out to attract paying customers. Several were pregnant. This was somehow their fault, and they were shunned and castigated accordingly. Mr Blaney felt that the presence of a pregnant girl would be morally harmful to the rest of the prisoners.

Neglected Child. — Julia Hudson, a girl twelve years of age, was brought up as a neglected child. Senior-constable Brinkley gave evidence to the effect that he had known the girl for about four years. Her father was dead, and her mother was supposed to be living at Maryborough. The latter, while a resident of this city, was a disreputable character. He arrested the girl on Tuesday in a house of ill-fame in Burnett Lane. She had been living there about a fortnight. She had been seen about the streets at late hours. The Bench ordered her to be sent to the Reformatory at Toowoomba for a period of three years.[iii]

A NEGLECTED CHILD. SEVEN YEARS IN THE REFORMATORY.

Elizabeth Shields was brought up, on remand, at the City Police Court yesterday morning, before Mr. P. Pinnock, P.M., as a neglected child.

Mr. Whiting, inspector to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty, stated that he had known the defendant for about two years. He also knew her mother and two sisters. He had often seen defendant going into the Chinese houses in Albert-street. Some twelve months ago he had occasion to be in the neighbourhood of Mrs. Shields’s house in Mary-street. He heard Mrs. Shields’s voice in a very angry tone. He heard her say to the child, “You are 10 years old now. You will have to go out and get money. “You must talk to men in the street. That ________ Bertha got £2 the other day and did not give me any of it.” He had seen men frequently going into the house at night. He had never seen defendant’s father. Defendant’s sisters were living at defendant’s mother’s house. Defendant’s mother told witness that defendant was 11 years of age. One of her sisters was 16 years of age.

Other witnesses were called, including Constable Fahey, who stated that the defendant’s sister Bertha kept the company of larrikins.

Defendant’s mother was called for the defence and said that she took in washing. She sometimes took a glass of beer, but she had never been incapable. The statements as to the morality of her daughters were quite incorrect. She had lately done washing for several persons working on steamers as well as other persons.

By Mr. DURHAM: Defendant would be 13 next birthday.

Defendant was ordered to be sent to the Industrial School at Toowoomba for a period of seven years.[iv)

The best that the Toowoomba girls could hope for was a license to work as a skivvy for a respectable family. The worst was to be “removed to the Hospital for the Insane” when bread and water didn’t cure high spirits.

The Hospital and Benevolent Asylum

If you were ill and poor, medical treatment was hard to obtain. The Brisbane Hospital received limited Treasury funds, and made up some of the shortfall by a subscription service, taking regular payments from worthy citizens for their possible future care in the institution. In reality, they subsidised the ailing poor, who, if they could not find a nice middle-class person to give them a ticket to the hospital, showed up nervously for admission and had to prove that they were not loafing about at the public’s expense. Given the accounts of the food and patient treatment, it seems unlikely that anyone would subject themselves to cold, greasy beef tea unless they absolutely had to. Emergency cases were always taken though. Negotiations for repayment would start once death or recovery occurred.

Part of the Brisbane Hospital since its inception in George Street in the post-convict era, was the Benevolent Asylum. This institution provided some shelter for the aged and destitute, often in tents in the grounds (‘outdoor relief’), and for those who did not need shelter, but were hungry, a small credit at a local shop for basic foodstuffs.

This activity strained the resources of the Hospital, and a compromise was found – separating the Hospital from the Benevolent Asylum. Thus in 1865, the aged, helpless and infirm were removed to the former quarantine station at Dunwich on Stradbroke Island in Moreton Bay.

While living out the twilight of one’s life at the seaside sounds agreeable, Dunwich was underfunded and poorly staffed. It was a long way from town by steamer, and those who went there could be forgiven for feeling that they were out of sight and out of mind. They were.

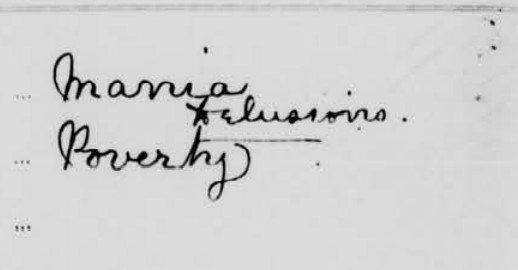

The Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum took in a lot of people “suspected of lunacy,” who were in fact very poor and malnourished, and were able to be discharged once their bodily health improved. Their case notes show various causes of their mental illness – “cause – poverty,” “solitude and misfortune,” “debt” and “privation.” Happily, the majority of these patients were, once rested and properly fed, able to go home without the need for readmission.

Unfortunate Women

There weren’t many choices available to unmarried or widowed women in the 1800s, particularly poor women. A middle-class spinster or widow, likely to have more education, could work as a governess, or at worst be a gentlewoman in distress, living on the goodwill of her family, and often nursing them all through various confinements and slow deaths.

A poor woman alone had to earn her own money to survive. She could go into service, providing she could produce references, and had no shame attached to her. One capricious or mean-spirited employer, one unwise liaison, and she would be turned out without a character. No unemployment benefit, no single parent pension, no widow’s pension, just grinding poverty and ostracism.

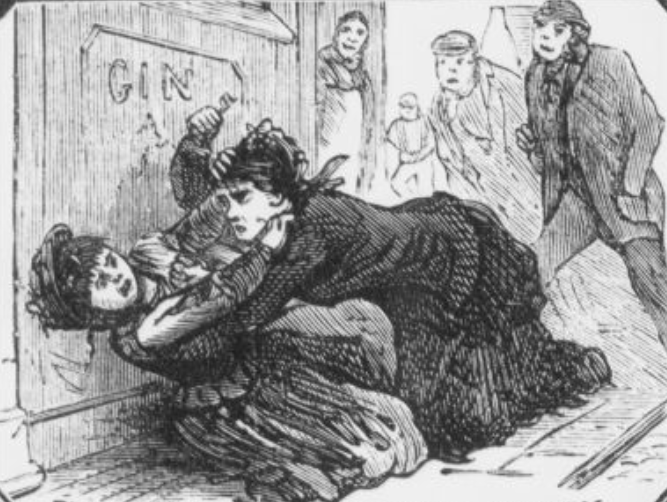

The option most often presented was to become a ‘soiled dove.’ Prostitution was fraught with physical and legal dangers. The prospect of disease, arrest or violence had to be weighed against the prospect of starvation. These women were not considered frail enough for a Benevolent Asylum.

Many of the prostitutes of the time were hard drinkers, racking up endless convictions in the Courts until they were too old and ill to continue working the streets.

Annie Bolton, whose mother Susan kept a brothel in Frog’s Hollow, came into the family business after a liaison led to an illegitimate child, whose paternity she could not establish satisfactorily for the Courts in 1875. She drank heavily over the next 20 years, losing her daughters, first to the Orphanage, then to the Toowoomba Reformatory. At the time of the girls’ admission to the Reformatory, Annie was doing one of her 10 prison sentences for swearing and drunkenness.

An Unfortunate Woman.

You Can Hang me if You Like.

When Annie Bolton, aged 33, with a record of 74 convictions, was bought before Mr Pinnock, police-magistrate, this morning to answer the charge of disorderly conduct and using obscene language, she said – in reply to the usual question, “How do you plead?” – that she was guilty, and intimated to Mr Pinnock that he could if he liked hang her. Mr Pinnock said he could not do that. The closely packed crowd of persons who had come to regale their ears and sight with scenes lamentable, on hearing the expression of utter abandonment of the unfortunate woman, were greatly amused, and expressed themselves in audible smiles. Mr Pinnock, however, at once checked this outburst of merriment at another’s woes, and administered a severe rebuke, stating that it was only due to the conduct of such men as they that the woman had fallen so low.[i]

Marriage helped, if there was enough work to put food on the table, the family enjoyed good health and some degree of harmony. For those less fortunate, the struggle could ruin your health, sanity and life.

A determined attempt to commit suicide was made by a woman named Maria Baker on Saturday. About 1 o’clock on that day, Mr Cornell, residing at Doughboy Creek, saw the woman throw herself into the river opposite the North Quay, as he was crossing in a ferry boat. With the assistance of the ferry-man he took her out. He immediately informed Sergeant McCollopy, who proceeded to the North Quay ferry steps, and found her sitting on the seat at the ferry shed, with the few articles of clothing she had on drenched with water and shivering with cold. In answer to the Sergeant, she said, “I am not a drunkard, nor am I drunk; I had a quarrel with my husband today; he took my last little one with me; he’s just gone away to Maitland; I have lost all my money; it was better for them to let me die, for I will drown myself yet.” When taken out of the water she also asseverated that she would drown herself. McCollopy conveyed the poor woman to the lock-up, and she will be brought before the Police Court this morning. It appears that she is the wife of Robert Baker, late of Adelaide Street. She has resided fourteen years in Sydney and four in Rockhampton. On Saturday her husband left her to look for work, and went in the direction of Milton, taking their son with him. When the Bakers came to Brisbane, they were, we understand, in very good circumstances.[ii]

Maria Baker saw her husband Robert return from his journey to find work, but they quickly descended into alcohol-fueled mutual loathing. Six years later, in December 1873, a thin and harried Maria Baker was hurrying along Charlotte Street, bearing a plate with meat and some vegetables for her husband. He had reluctantly parted with half a crown for this purpose; both of them had been drinking for several days, and dinner was a peace offering. The exertion of running must have been too much for her battered constitution, because she fell flat on her face and did not get up. A miner named Thomas Amand, a resident of the Auckland Boarding House, saw her fall and went to her assistance. By the time he’d picked her up and put her on the footpath, she was beyond all help.

Sergeant Driscoll responded to the hue and cry, and recognizing the dead woman, went to the Baker home off Charlotte Street to inform her husband. A little boy had already told Baker of his wife’s death, and Robert Baker was seething drunk and in no mood for sentiment.

“Are you aware that your wife is dead?” Robert Baker replied, “I am.” The Sergeant asked, “Why don’t you take her off the street?” Mr Baker said, “I leave that for you to do.’

With growing incredulity, the officer asked if Baker refused to allow her to be brought into the house, and he replied, “I do, that’s plain enough.” Driscoll directed that the poor woman be taken to the morgue.

The following day, at an inquest convened by an appalled Police-Magistrate, Robert Baker gave evidence that he was drunk when the Sergeant Driscoll came to see him, and had thought that his wife was merely in a fit, not dead. She was prone to fits, he said. “As soon as I heard she was dead I gave orders for her burial. If I had been in my sober senses, I should not have acted in that way; she was buried at 10 o’clock this morning.”

Dr O’Doherty gave evidence that Maria Baker had died of apoplexy, and the Police-Magistrate made a finding to that effect and closed the inquest.[iii] And probably made a mental note to appreciate his own family a little more.

We want bread, and bread we must have!

William Eaves, one of the Brisbane rioters. 11 Sept 1866.

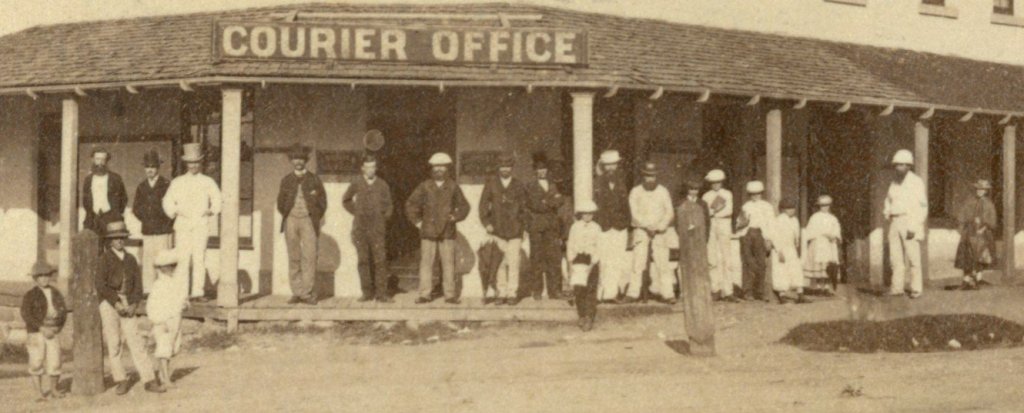

In July and August 1866, the Queensland government was desperately short of funds. There was no money available for infrastructure programs, such as the railways, and drought had ruined the agricultural sector. Workers were still being shipped in their hundreds from England and Europe, and there was no work for them in Brisbane or Ipswich. Suddenly unemployed, local railway labourers (“navvies”) found themselves and their families with no work and nothing to eat.

On 6 September 1866, a group of desperate navvies broke into the railway stores at Helidon, in search of rations. Rumours spread of a small army of navvies on the march to Brisbane, intent on a confrontation with the Government. Indeed, about 250 men had arrived by train in Ipswich and, lacking any public transport from there to Brisbane, continued on foot.

By the time the navvies arrived in the capital (their ranks considerably thinned to 175), the unemployed of Brisbane were there to join them in protest. Speeches were made, concessions were offered and considered, and it seemed that the trouble might be at an end.

However, a breakaway group, led by a firebrand named William Eaves and other representatives of the Brisbane unemployed, resolved to keep up the fight. A night-time meeting was proposed – all the better to conceal their identities.

On the night of 11 September 1866, an angry crowd formed outside the Treasury Building, estimated at around 500 people. Their object was to storm the Government Stores for food, and this they attempted by throwing stones on the roof and trying to force the doors.

The Police and Volunteers assembled quickly and drove the protesters down Elizabeth Street. Volleys of stones thrown by protesters greeted their every move. Eventually the Police Magistrate had the Riot Act read (literally), and for his pains, took a stone to the forehead. The Police were directed to use live ammunition, and the sight of Magistrate Massey with blood on his face shocked the more reasonable of the protesters.

Eventually, a determined bayonet charge by the authorities broke the back of the crowd, and it began to disperse down the side streets and disappear into the night. It is surprising that no-one was killed, and so few injured. The most serious injuries were stone-cuts to Police and the Magistrate.

Eaves and his deputies, Parker and Murray, were gaoled. Concessions were made to the unemployed – some were given assistance to relocate to northern centres, and basic, but welcome, relief programs were put in place for the navvies and their dependents. These Government concessions were the first step in the direction of a social welfare policy.

Nearly thirty years later, a confrontation between shearers and the graziers who employed them led to the birth of the Labour party, just before Federation meant that Australians were albe to self-govern.

Landowners, keen to avoid what they considered to be the high cost of union shearers, who had been working for them for years, attempted to employ cheap labour. The shearers organised against this, and the Colonial Government rallied troops. Hardship and violence followed. Men were gaoled, then discharged as heroes of the Labour movement. But the idea of protection for workers began to take hold, and the helpless poverty of Colonial times gradually became a thing of the past.

Occupations of the Proserpine Children, 1870–1880

(Childhood and adolescence are modern inventions.)

An inmate of the Orphanage 6

Attending School 29

Barman 1

Begging 2

Bootmaking 1

Cabin Boy 2

Cutting wood 1

Draper’s Assistant 1

Driving a baker’s cart 1

Employed in a brothel 2

Errand Boy 2

Farmer 1

Grocer 1

Groom 2

Hawking fruit 1

Labourer 3

Living with the blacks 1

Messenger at the Club 1

Minding Cattle 1

Newspaper Boy 1

Nil/Not stated 88

Office Boy 1

On a station 1

Ordinary Seaman 3

Page 1

Running a mail 1

Saddler 1

Shepherd 1

Stockriding 2

Travelling with a saddler 1

Travelling with his Father 1

With a milkman 1

Woodcutting 2

Working at a boarding house 1

Working in a hotel 1

Working in a shop 1

Working on a farm 7

Working on a station 1

Total 175

[i] Fitzgerald, Ross. History of Queensland from the dreaming to 1915. University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland, 1982.

[i] Telegraph, 10 March 1891

[ii] Warwick Argus and Tenterfield Chronicle, 26 July 1867

[iii] Telegraph, 03 December 1873

[ii] Rockhampton Bulletin, 03 October 1877

[i] Darling Downs Gazette and General Advertiser, 14 January 1874

[iii] Telegraph, 10 February 1881

[iv] Brisbane Courier, 8 August 1893