Imagine being a Census collector in the 19th century – particularly in the vast but sparsely populated Colony of Queensland. Travelling by road and river to remote hamlets, shepherd’s huts and stations in all weathers and probably at some personal risk, in order to determine who lived where, who did what, and what were their educational standards and religious persuasions.

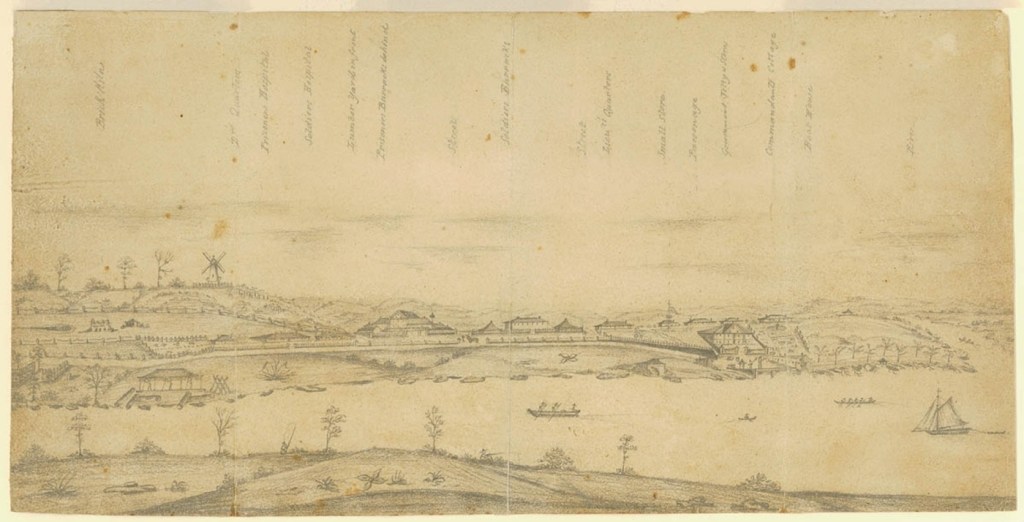

During the period before 1859, when we were still part of New South Wales, the census showed our gradual transition from semi-abandonded convict settlement to a region that might take on self-government.

The Moreton Bay Convict Settlement

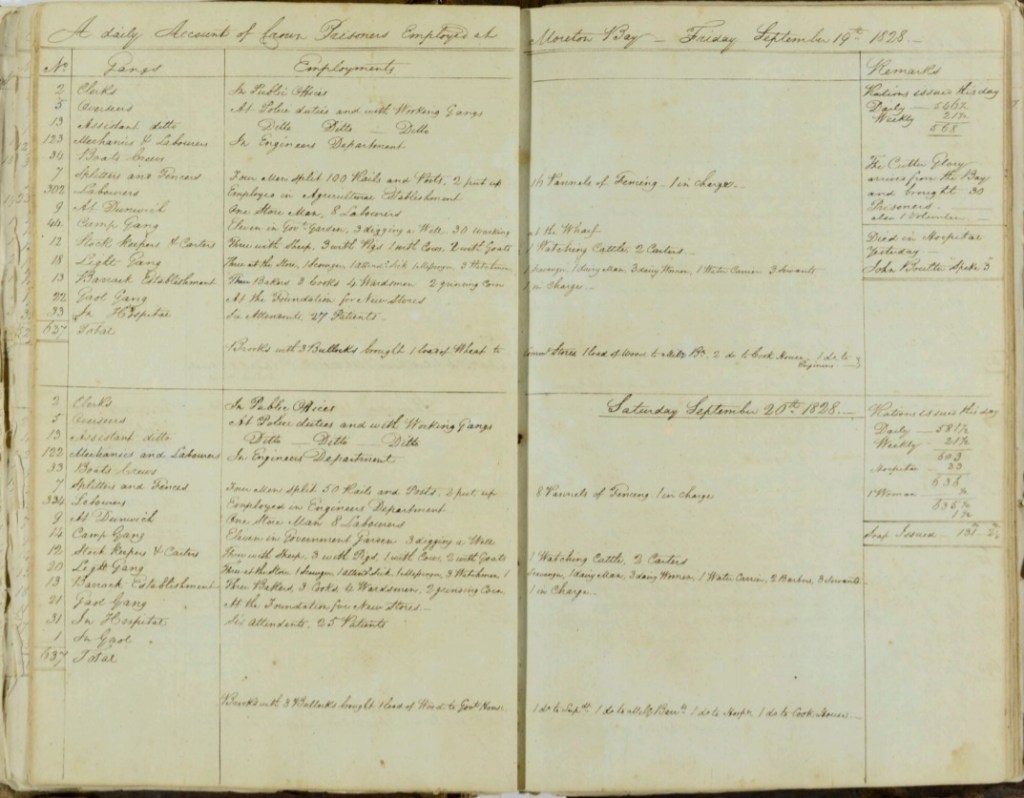

From 1824 to 1839, the Census returns were straightforward – the Convict Settlement was pretty much all there was. The Commandant reported the number of convicts, Government workers, and military personnel to the Governor each month. Spicer’s Diary provided a daily view of the comings and goings.

Brigs and schooners brought new prisoners and took away those whose sentences had expired. Births (usually children of the military) were recorded, as were convict absconders and deaths. The only civilian establishment in the region was the German Station at North Brisbane.

Nobody thought to properly survey the indigenous people of the area, although the successive Commandants estimated the declining numbers in the area. Probably to illustrate how well the threat was being managed by the British Army.

1841 – The End of the Convict Settlement.

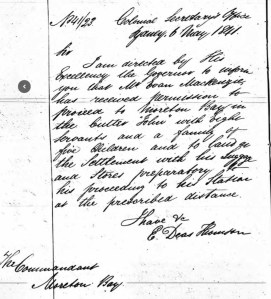

In 1841, Commandant Gorman began receiving letters from the Colonial Secretary to the hitherto isolated settlement, notifying him of settlers and their servants who had been given permission to berth and travel overland to establish grazing and agricultural concerns to the north and west of Brisbane Town. At the same time, most of the convicts had been returned to Sydney, with the residue remaining in assigned service or labour.

A Census of the Colony of New South Wales was undertaken, and the results showed Moreton Bay in a rather pitiful light. The only people there were soldiers, bureaucrats, their families and convict servants.

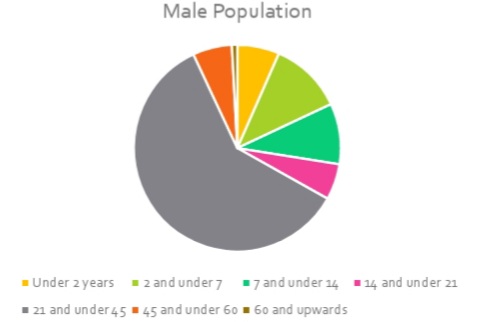

There were 26 children, 2 adolescents, 156 adult men, and 16 adult women, making up a grand total of 200 people. Males outnumbered females 176 to 24, and the largest portion of the population comprised men 21 -45 years of age.

1846 – The First Free Settlement Census

By the time of the 1846 Census, there were only two settled areas to be reported on – Stanley County (including Brisbane) and the Darling Downs.

The total population measured as Stanley County was 1599 – 1121 males and 478 females. The County was measured as including North and South Brisbane, Ipswich, squatting stations in the surrounding areas, plus Military and Government establishments. Census records in later years would separate out Ipswich and the rural areas, leaving Stanley County as Brisbane and its immediate surrounds. In that entire district, there were 205 finished dwellings, largely simple timber houses.

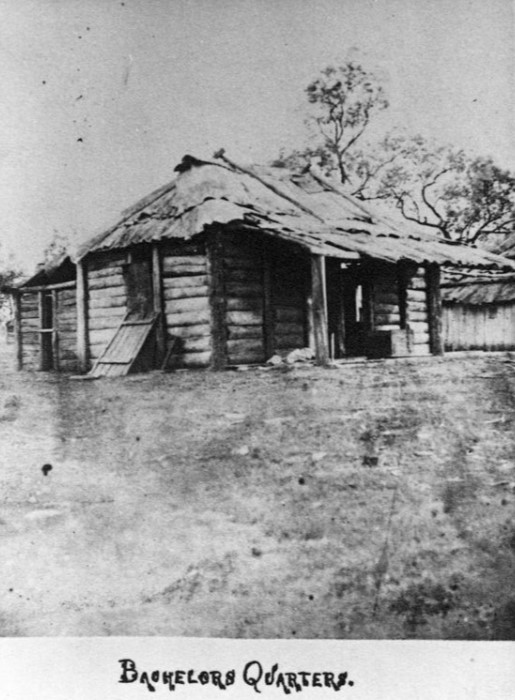

Bijou accommodation for the Colony’s many bachelor shepherds.

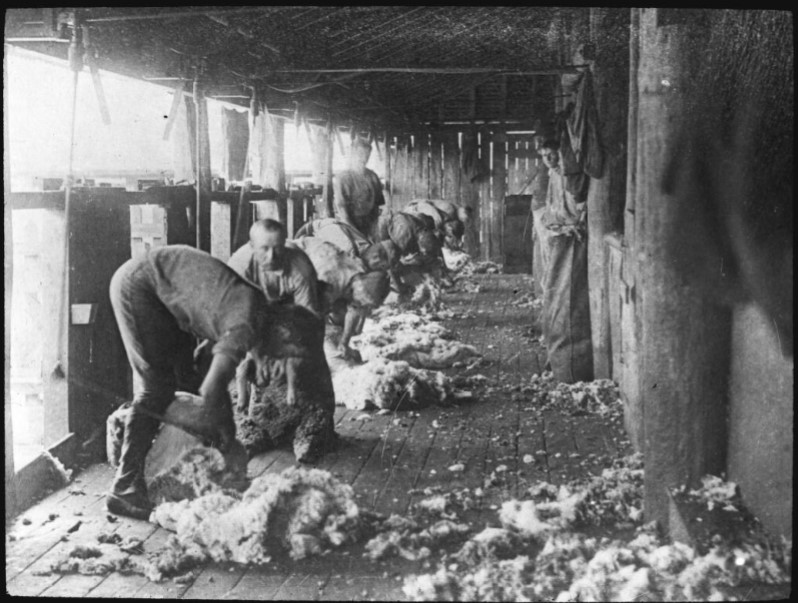

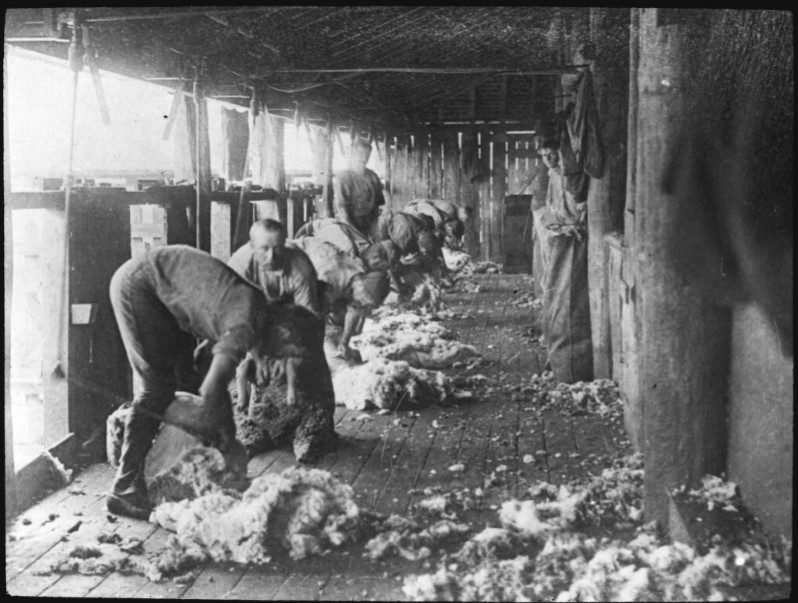

Shearing

Wool transports.

Brisbane Town itself now numbered 829 people (508 male, 321 female) with the rest of the population on outstations and in the Military establishments. Moreton Bay settlers were optimistic people, establishing a newspaper that year, and lobbying the Governor for skilled immigrants and infrastructure, despite a fragile economy.

The survey’s capture of so much rural territory meant that most workers recorded were single young men working as shepherds or in working on the sheep holdings around the south-east. The portion of the population originating in the UK was 1115, and Australian-born residents numbered 382.

Literacy rates were sound in adults, and Anglicans led the religious persuasions. There were 14 clerics, 2 lawyers and 2 doctors. Mechanics and artificers (skilled craftsmen) were many, and there were still convicts about – 7 in assigned service, and 128 ticket of leave holders.

1851 – Free Settlement Expands

The population of Stanley County had more than doubled in six years, with a particular increase in females (from 478 to 1846 women). Brisbane now had 1480 men and 1063 women. The principal towns in this part of the Colony were Brisbane, Drayton, Gayndah, Grafton (now in New South Wales), Ipswich, Maryborough and Warwick. The mineral boom had yet to arrive in the North and on the Central Coast, making Maryborough the northernmost principal town.

In terms of occupations, mechanics/artificers (335) were rivalling commerce/trade (346) and shepherding/sheep management (461).There were now 262 ticket of leave holders, showing the continued post-convict influence in the North. Roman Catholics were on the increase, as were people classified as “Mahomedan” and “Pagan.” (Chinese and Pacific Islander people were among those classified as pagan.)

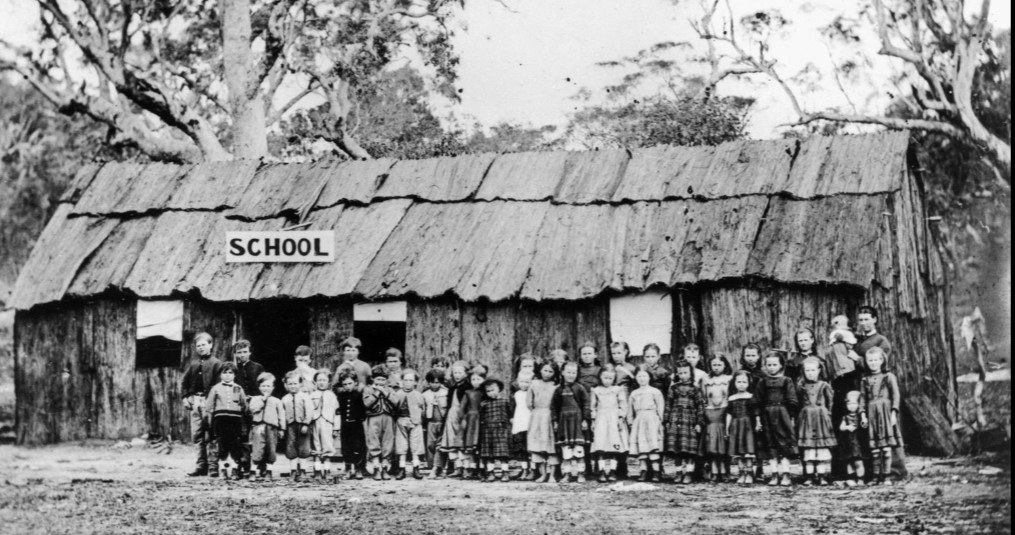

There were twice as many single people as married in Stanley. The number of Australian-born residents had doubled, as had Irish-born residents. The quantity of English-born residents remained largely the same. A new category appeared in Civil Condition – pensioners and paupers. Brisbane had 5 pensioner/paupers. The number of clerics remained at 14, but we now had 17 doctors and 8 lawyers. Literacy rates remained sound for adults, but fairly poor for children and young people.

1856 – The Last Census as part of New South Wales

The Irish population was increasing significantly, almost equalling the number of Australian-born residents. English-born people still dominated the statistics, and single men and women continued to outnumber married people.

Female occupations beyond domestic service were recorded for the first time – teaching, and trade or commerce. For men, the number involved in agriculture and grazing of sheep and cattle had declined, and the work of trade, commerce and unskilled labour occupied them instead..

Education levels for children and young people became a genuine concern. In the Brisbane Police District, only 31 children aged 7 and under could read and write. 295 children aged 7 and under could not (these statistics do not include children under 4, who were not expected to know their letters).

Adult and older Brisbane residents enjoyed literacy rates exactly the opposite of those of the children. For example, amongst males 21-45 years, 1444 could read and write, and 179 were illiterate.

Brick and timber dwellings made up the bulk of the dwellings, only 2 people lived in tents, and mercifully no-one was reported as living in a dray (these were new housing sub-sets for 1856). Roofs were shingled, with only 5 dwellings making do with tin.

The population of Stanley County stood at 9875 in 1856, and the campaign to separate the districts north of the Tweed River from the administrative control of Sydney was advancing.

The growth from 200 people to nearly 10,000 in Stanley/Brisbane alone, as charted by the census, meant that the northern districts of New South Wales could stand a chance of becoming an independent Colony, without provoking the paroxysms of mirth from Sydney legislators that greeted the early Separation movement in 1851.